Chapter 3: Acids and Bases: Introduction to Organic Reaction Mechanism Introduction

3.2 Organic Acids and Bases and Organic Reaction Mechanism

3.2.1 Organic Acids

The acids we discussed in general chemistry usually refer to inorganic acids, such as HCl, H2SO4, and HF. If the structure of the acid contains a “carbon” part, then it is an organic acid. Organic acids donate protons in the same way as inorganic acids, but their structure may be more complicated due to the nature of organic structures.

Carboxylic acid, with the general formula of R-COOH, is the most common organic acid we are familiar with. Acetic acid (CH3COOH), an ingredient in vinegar, is a simple example of a carboxylic acid. The Ka of acetic acid is 1.8×10-5.

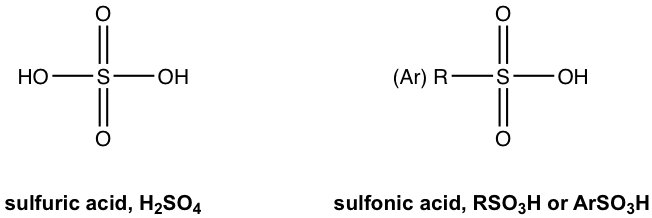

Another common organic acid is the organic derivative of sulfuric acid H2SO4.

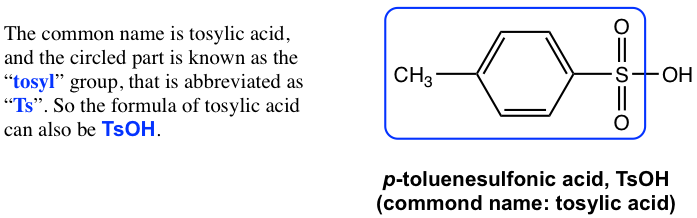

The replacement of one OH group in H2SO4 with a carbon-containing R (alkyl) or Ar (aromatic) group leads to the organic acid named “sulfonic acid” with the general formula of RSO3H, or ArSO3H. Sulfonic acid is a strong organic acid with a Ka in the range of 106. The structure of a specific sulfonic acid example called p-toluenesulfonic acid is shown here:

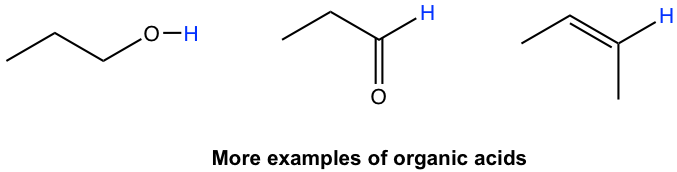

Other than the acids mentioned here, technically, any organic compound could be an acid because organic compounds always have hydrogen atoms that could potentially be donated as H+. A few examples are shown here with the hydrogen atoms highlighted in blue:

Therefore, the scope of acids has been extended to be broadly extended in an organic chemistry context. We will have further discussions on the acidity of organic compounds in section 3.3, and we will see more acid-base reactions applied to organic compounds later in this chapter.

3.2.2 Organic Bases

While it is relatively straightforward to identify an organic acid since hydrogen atoms are always involved, it is not always easy to identify organic bases. According to the definition, a base is a species that is able to accept protons. Organic bases may involve a variety of different structures, but they must all share the common feature of having electron pairsthat are able to accept protons. The electron pairs could be lone pair electrons on a neutral or negatively charged species or π electron pairs. Organic bases could therefore involve the following types:

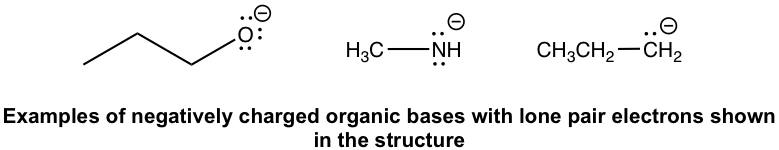

- Negatively charged organic bases: RO–(alkyloxide), RNH–(amide), and R–(alkide, the conjugate base of alkane). Since the negatively charged bases have a high electron density, they are usually stronger bases than the neutral ones.

- Neutral organic bases, for example, amine, C=O group and C=C group

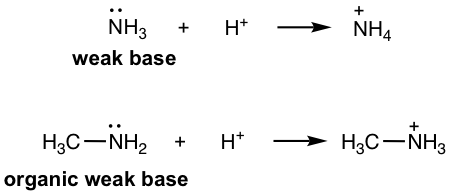

- Amine: RNH2, R2NH, R3N, ArNH2, etc. (section 2.3). As organic derivatives of NH3, which is an inorganic weak base, amines are organic weak bases with lone pair electrons on N that are able to accept the protons.

-

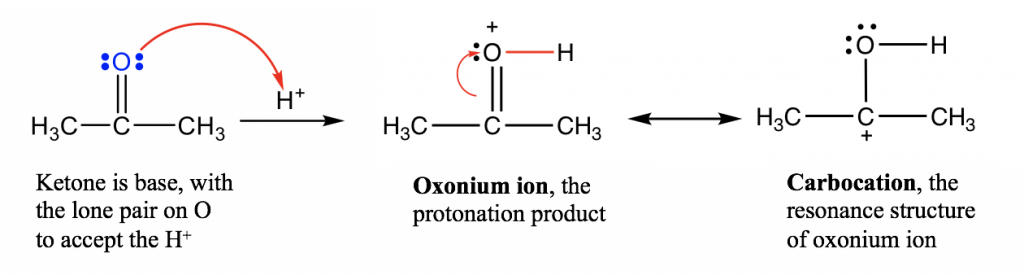

- Functional groups containing oxygen atoms: carbonyl group C=O, alcohol R-OH, and ether R-O-R. The lone pair electrons on O in these groups are able to accept the protons, so functional groups like aldehyde, ketone, alcohol and ether are all organic bases. It may not be easy to accept this concept at first because these groups do not really look like bases. However, they are bases according to the definition because they are able to accept the proton with the lone pair on the oxygen atom.

Notes for the above mechanism:

- For the acid-base reaction between the C=O group and the proton, the arrow starts from the electron pair on O and points to the H+ that is receiving the electron pair. A new O-H bond is formed as a result of this electron pair movement.

- In this acid-base reaction, the ketone is protonated by H+ so this reaction can also be called the “protonation of ketone”.

- The product of the protonation is called an “oxonium ion”, which is stabilized with another resonance structure, carbocation.

-

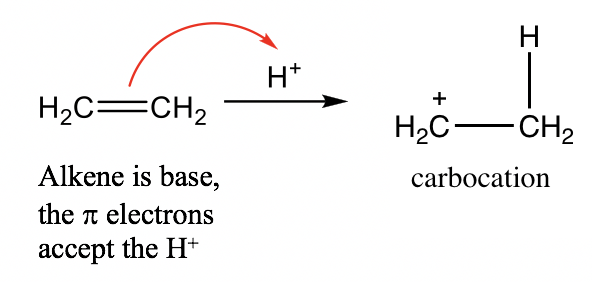

- Alkene (C=C): Although there are no lone pair electrons in the C=C bond of alkene, the π electrons of the C=C double bond are able to accept protons and act as a base. For example:

Example: Organic acid and base reaction

Predict and draw the products of the following reaction and use the curved arrow to show the mechanism.

Approach: If H+ is the acid as in previous examples, it is rather easy to predict how the reaction will proceed. However, if there is no obvious acid (or base) as in this example, how do you determine which is the acid, and which is the base?

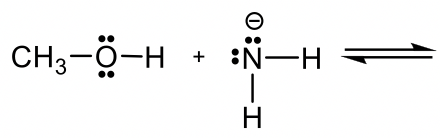

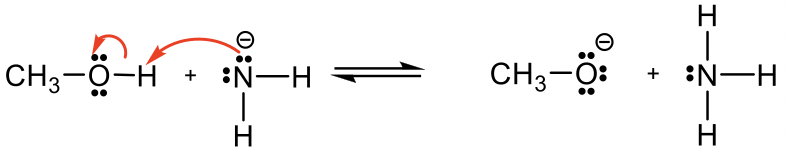

Methanol CH3OH is neutral, and the other reactant, NH2–, is a negatively charged amide. The amide with a negative charge has higher electron density than the neutral methanol, therefore amide NH2–should act as base, and CH3OH is the acid that donates H+.

Solution:

Exercises 3.1

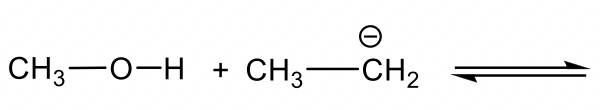

Predict and draw the products of the following reaction and use a curved arrow to show the mechanism.