Chapter 9: Free Radical Substitution Reaction of Alkanes

9.2 Halogenation Reaction of Alkanes

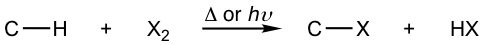

When alkanes react with halogen (Cl2 or Br2), with heat or light, the hydrogen atom of the alkane is replaced by a halogen atom, and alkyl halide is produced as a product. This can be generally shown as:

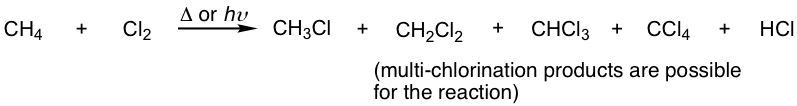

A specific example is:

Such a type of reaction can be called substitution because hydrogen is substituted by halogen; it can also be called halogenation because halogen is introduced into the product. For this book, both terms are used in this chapter, interchangeably.

The net reaction for halogenation seems straightforward, but the mechanism is more complicated though, as it goes through multiple steps, including initiation, propagation, and termination.

We will take the following example of the mono-chlorination of methane for the discussion of reaction mechanisms.

CH4 + Cl2 → CH3Cl + HCl

Mechanism for the mono-chlorination of methane:

Initiation: Production of radicals

![]()

With the energy provided by heat or light, chlorine molecules dissociate homolytically, and each chlorine atom takes one of the bonding electrons, and two highly reactive chlorine radicals, Cl•, are produced.

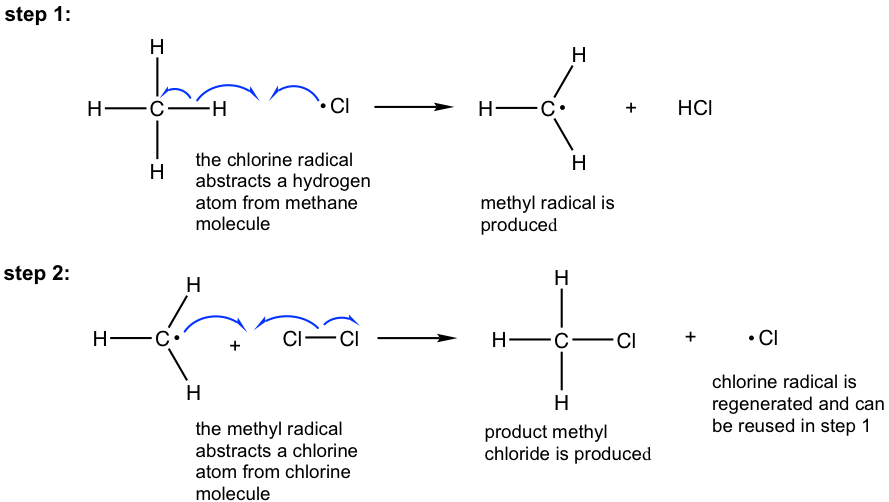

Propagation: Formation of the product and regeneration of radicals

The propagation step involves two sub-steps. In the 1st step, the Cl• takes a hydrogen atom from the methane molecule (this is also called hydrogen abstraction by Cl•), and the C-H single bond breaks homolytically. A new σ bond is formed by Cl and H, with each donating one electron and HCl is produced as the side product. The CH3 radical, CH3•, the critical intermediate for the formation of the product in the next step, is formed as well.

In the 2nd step, the CH3• abstracts a chlorine atom to give the final CH3Cl product together with another Cl•. The regenerated Cl• can attack another methane molecule and cause the repetition of step 1, then step 2 is repeated, and so forth. Therefore, the regeneration of the Cl• is particularly significant, as it makes the propagation step self-repeat hundreds or thousands of times. The propagation step is therefore called the self-sustaining step, and only a small amount of Cl• is required at the beginning to initiate the process.

Initiation and propagation are productive steps for the formation of a product. This type of sequential, step-wise mechanism in which the earlier step generates the intermediate that causes the next step of the reaction to occur, is called a chain reaction.

The chain reaction will not continue forever though, because of the termination steps.

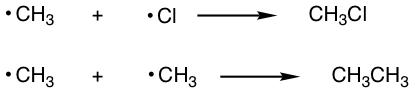

Termination: Consumption of radicals

When two radicals in the reaction mixture meet with each other, they combine to form a stable molecule. The combination of radicals leads to a decrease in the number of radicals available to propagate the reaction, and the reaction slows and stops eventually, so the combination process is called the termination step. A few examples of termination are given above, and other combinations are possible as well.

When two radicals in the reaction mixture meet with each other, they combine to form a stable molecule. The combination of radicals leads to a decrease in the number of radicals available to propagate the reaction, and the reaction slows and stops eventually, so the combination process is called the termination step. A few examples of termination are given above, and other combinations are possible as well.

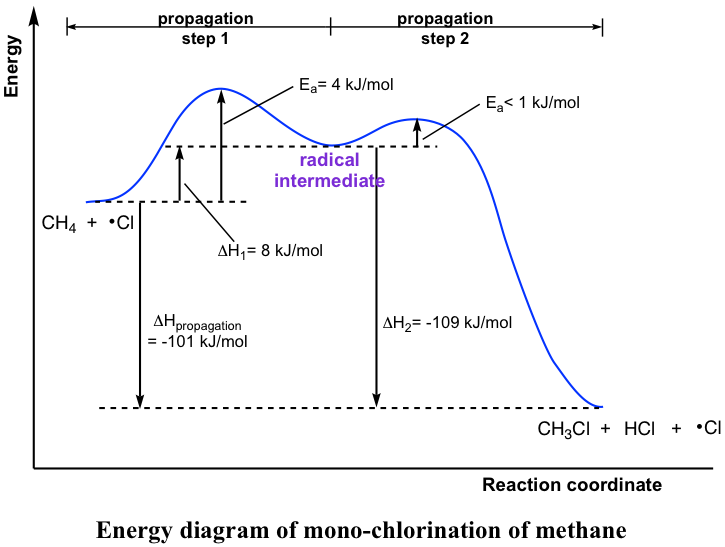

The propagation steps are the core steps in halogenation. The energy level diagram helps to provide a further understanding of the propagation process.

The 1st step in propagation is endothermic, while the energy absorbed can be offset by the 2nd exothermic step. Therefore, the overall propagation is an exothermic process, and the products are at a lower energy level than the reactants.

The reaction heat (enthalpy) for each of the propagation steps can also be calculated by referring to the homolytic bond dissociation energies (Table 9.1). For such a calculation, energy is absorbed for the bond-breaking step, so the bond energy is given a “+” sign, and for the energy released for the bond-forming step the “-” sign is applied.

| Bond |

kJ/mol |

Bond |

kJ/mol |

Bond |

kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A — B → A • + B • | |||||

| F — F | 159 | H —Br | 366 | CH3 — I | 240 |

| Cl — Cl | 243 | H — I | 298 | CH3CH2 —H | 421 |

| Br — Br | 193 | CH3 — H | 440 | CH3CH2 —F | 444 |

| I — I | 151 | CH3 — F | 461 | CH3CH2 —Cl | 353 |

| H — F | 570 | CH3 — Cl | 352 | CH3CH2 — Br | 295 |

| H — Cl | 432 | CH3 — Br | 293 | CH3CH2 — I | 233 |

Table 9.1 Homolytic Bond Dissociation Energies for Some Single Bonds

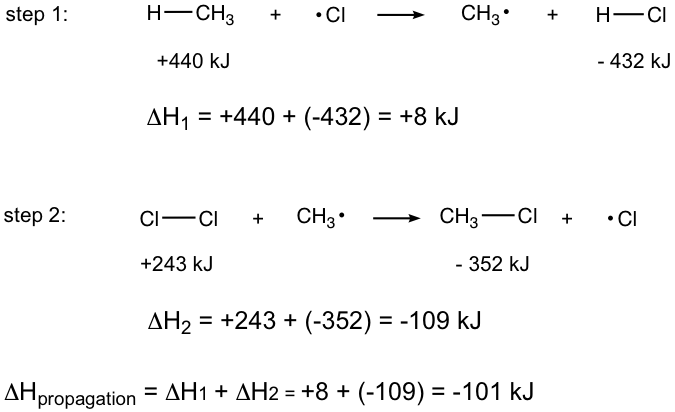

Examples: Calculate the reaction energy for the propagation step of mono-chlorination of methane (referring to the corresponding bond energies in Table 9.1.).

Solution:

Step 1: H — CH3 + •Cl → CH3• + H — Cl

The H — CH3 bond broken, absorb energy, so +440 kJ

The H — Cl bond formed, release energy, so – 432 kJ

ΔH1 = +440 + (-432) = +8 kJ

Step 2: Cl — Cl + CH3• → CH3 — Cl + •Cl

The Cl — Cl bond broken, absorb energy, so +243 kJ

The CH3 — Cl formed, release energy, so -352kJ

ΔH2 = +243 + (-352) = – 109kJ

ΔHpropagation = ΔH1 + ΔH2 = +8 + ( – 109 ) = – 101kJ

The calculated data does match with the data from the energy diagram.

Reactivity Comparison of Halogenation

The energy changes for halogenation (substitution) with the other halogens can be calculated similarly. The results are summarized in Table 9.2.

| Reaction |

F2 |

Cl2 |

Br2 |

I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1:

H — CH3 + •X → CH3• + H — X |

-130 | +8 | +74 | -142 |

| Step 2:

X — X + CH3• → CH3 — X + • X |

-322 | -109 | -100 | -89 |

| Overall propagation:

H — CH3 + X — X → CH3 — X + HX |

-452 | -101 | -26 | +53 |

Table 9.2. Enthalpy of the Propagation Steps in Mono-halogenation of Methane (kJ/mol)

The data above indicate that the halogen radicals have different reactivity; fluorine is the most reactive, and iodine is the least reactive. The iodine radical is very unreactive with overall “+” enthalpy, so iodine does not react with alkane at all. On the other side, the extremely high reactivity of fluorine is not a benefit either. The reaction for fluorine radical is vigorous and even dangerous with a lot of heat released, and it is not practical to apply this reaction for any application because it is hard to control. So, Cl2 and Br2, with reactivity in the medium range, are used for halogen substitutions of alkanes. Apparently, Cl2 is more reactive than Br2, and this leads to the different selectivity and application between the two halogens. This is further discussed in section 9.4.