Interpersonal Communication

We communicate with each other to meet our needs, regardless of how we define those needs. From the time you are a newborn infant crying for food or the time you are a toddler learning to say “please” when requesting a cup of milk, to the time you are an adult learning the rituals of the job interview and the conference room, you learn to communicate in order to gain a sense of self within the group or community–meeting your basic needs as you grow and learn.

Interpersonal communication is the process of exchanging messages between two people whose lives mutually influence one another in unique ways in relation to social and cultural norms (University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2013). A brief exchange with a grocery store clerk who you don’t know wouldn’t be considered interpersonal communication, because you and the clerk are not influencing each other in significant ways. If the clerk were a friend, family member, coworker, or romantic partner, the communication would fall into the interpersonal category.

Aside from making your relationships and health better, interpersonal communication skills are highly sought after by potential employers, consistently ranking in the top ten in national surveys (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2010). Interpersonal communication meets our basic needs as humans for security in our social bonds, health, and careers. But we are not born with all the interpersonal communication skills we’ll need in life.

Social Penetration Theory

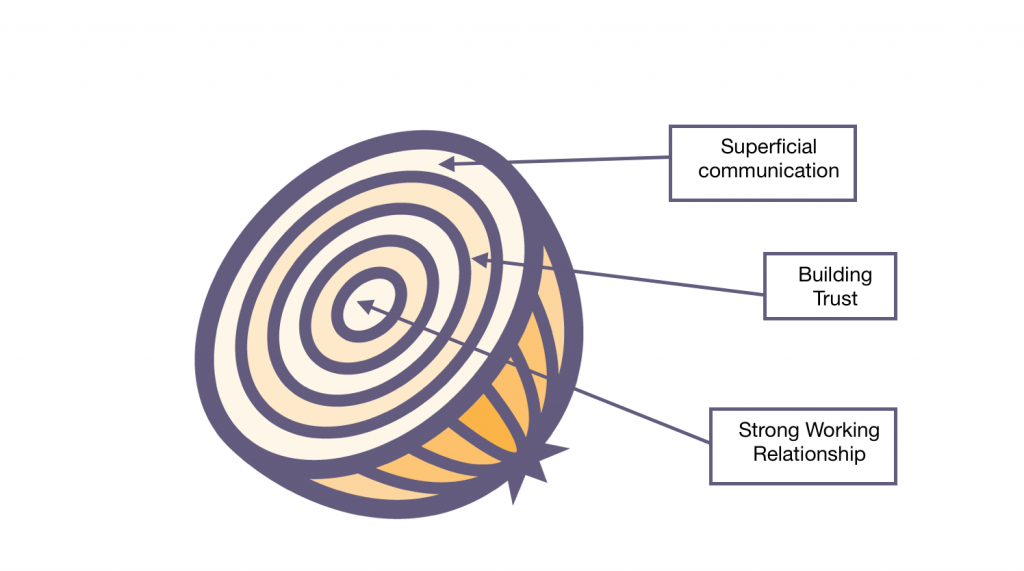

How do you get to know other people? If the answer springs immediately to mind, we’re getting somewhere: communication. Communication allows us to share experiences, come to know ourselves and others, and form relationships, but it requires time and effort. Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor describe this progression from superficial to intimate levels of communication in social penetration theory, which is often called the Onion Theory because the model looks like an onion and involves layers that are peeled away (Altman & Taylor, 1973). According to social penetration theory, we fear that which we do not know. That includes people. Strangers go from being unknown to known through a series of steps that we can observe through conversational interactions.

At the outermost layer of the onion, in this model, there is only that which we can observe. We can observe characteristics about each other and make judgments, but they are educated guesses at best. Our nonverbal displays of affiliation, like a team jacket, a uniform, or a badge, may communicate something about us, but we only peel away a layer when we engage in conversation, oral or written.

As we move from public to private information we make the transition from small talk to substantial, and eventually intimate, conversations. Communication requires trust and that often takes time. Beginnings are fragile times and when expectations, roles, and ways of communicating are not clear, misunderstandings can occur.

According to the social penetration theory, people go from superficial to intimate conversations as trust develops through repeated, positive interactions. Self-disclosure is “information, thoughts, or feelings we tell others about ourselves that they would not otherwise know” (McLean, 2005). Taking it step by step, and not rushing to self-disclose or asking personal questions too soon, can help develop positive business relationships. Figure 9.1 below, an image of onion layers resembles the process of building interpersonal communication relationships.

Principles of Self-Disclosure

From your internal monologue and intrapersonal communication, to verbal and nonverbal communication, communication is constantly occurring. What do you communicate about yourself by the clothes (or brands) you wear, the tattoos you display, or the piercing you remove before you enter the workplace? Self-disclosure is a process by which you intentionally communicate information to others, but can involve unintentional, but revealing slips.

Interpersonal Relationships

Interpersonal communication can be defined as communication between two people, but the definition fails to capture the essence of a relationship. This broad definition is useful when we compare it to intrapersonal communication, or communication with ourselves, as opposed to mass communication, or communication with a large audience, but it requires clarification. The developmental view of interpersonal communication places emphasis on the relationship rather than the size of the audience, and draws a distinction between impersonal and personal interactions.

For example, one day your coworker and best friend, Iris, whom you’ve come to know on a personal as well as a professional level, gets promoted to the position of manager. She didn’t tell you ahead of time because it wasn’t certain, and she didn’t know how to bring up the possible change of roles. Your relationship with Iris will change as your roles transform. Her perspective will change, and so will yours. You may stay friends, or she may not have as much time as she once did. Over time, you and Iris gradually grow apart, spending less time together. You eventually lose touch. What is the status of your relationship?

If you have ever had even a minor interpersonal transaction such as buying a cup of coffee from a clerk, you know that some people can be personable, but does that mean you’ve developed a relationship within the transaction process? For many people the transaction is an impersonal experience, however pleasant. What is the difference between the brief interaction of a transaction and the interactions you periodically have with your colleague, Iris, who is now your manager?

The developmental view places an emphasis on the prior history, but also focuses on the level of familiarity and trust. Over time and with increased frequency we form bonds or relationships with people, and if time and frequency are diminished, we lose that familiarity. The relationship with the clerk may be impersonal, but so can the relationship with the manager after time has passed and the familiarity is lost. From a developmental view, interpersonal communication can exist across this range of experience and interaction.

Regardless of whether we focus on collaboration or competition, we can see that interpersonal communication is necessary in the business environment. We want to know our place and role within the organization, accurately predict those within our proximity, and create a sense of safety and belonging. Family for many is the first experience in interpersonal relationships, but as we develop professionally, our relationships at work may take on many of the attributes we associate with family communication. We look to each other with similar sibling rivalries, competition for attention and resources, and support. The workplace and our peers can become as close, or closer, than our birth families, with similar challenges and rewards.

To summarize, interpersonal relationships are an important part of the work environment. We come to know one another gradually (layer by layer). The principle of self-disclosure is a normal part of communication.

Image Description

Figure 18.2 image description: This diagram shows three layers inside an onion symbolizing interpersonal communication. The outermost layer represents superficial communication, the middle layer represents building trust and the innermost layer represents a strong working relationship. [Return to Figure 18.2]