Chapter 6: Relationship Violence Models and Risk Factors

Balbir Gurm and Glaucia Salgado

Key Messages

- Relationship violence is an extremely complex health and social issue that requires expertise in multiple fields such as health, sociology, psychology, criminology, and justice.

- Understanding what makes someone at risk of violence (contextual and environmental factors) strengthens the effectiveness of interventions.

- Risk factors are identified to develop appropriate services and programs in order to safely plan programs to prevent abuse. Risk factors are a combination of environmental and social conditions and individual’s biology/genetics).

- Prevention and intervention programs need to be evidence-based, and the evidence can often come from practice.

- Other early intervention programs such as the Nurse-Family Partnership are also evidence-based strategies for intervention.

- Gendered violence will continue until there is a cultural shift about attitudes towards women and offender accountability (Iliadis, 2019).

- Relationship violence will continue until we recognize our own power and privilege and work toward creating equity and not oppression because violence exists against the whole spectrum of gender (Gurm, 2013).

- The world is becoming smaller and knowledge is shared freely through the internet. Therefore, in this section, we highlight what is known about relationship violence and successful initiatives from around the world.

Relationship violence (RV) is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Dixon & Graham-Kevan, 2011; Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is transgender (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death. Relationship violence impacts the physical, psychological, economic and social well-being of those who are abused (see chapter 5).

Most of the literature is about violence against women and girls (Dixon & Graham-Kevan, 2011) from a feminist perspective, and the literature is in silos. It is also normalized to heterosexual relationships from this perspective where men are seen as perpetrators and women as survivors (Dobash & Dobash, 1984, 2004), even though studies indicate that it is perpetrated by females on males in heterosexual groups and by sexual and gender diverse groups ( Archer, 2000, 2006; Dixon & Graham-Kevan, 2011; Jones, 2018; Lien & Lorentzen, 2019; Straus & Gelles, 1986; Walters et al., 2013). Please also note that we are aware that there are debates around how statistics are counted, and what is counted, leading to contradictions in figures from different studies – see chapter 5 for a fuller discussion of this point.

Gender (male or female)/sexual and gender diversity (LGBQT2SIA+) is only one of the contributing factors because relationship violence is a multifactorial issue. We acknowledge that after decades of addressing RV from the feminist perspective, we have over time seen policy changes and a move towards equity. With this understanding, we believe that knowledge from women’s programs and services may be adapted for use across genders, sexual and gender diverse groups. That does not mean services for women need to decrease, but all groups who suffer RV, with any prevalence, need to be served. However, we are also aware that Ristock (2002) argues that a simple, direct transfer of services without awareness of, and sensitivities to, the uniqueness of, in her case lesbian relationships, can have limited utility. See chapter 19 for Indigenous populations, chapter 20 for LGBTQ2SIA+ and chapter 21 for immigrants and refugees, for a fuller discussion of these nuances in serving the specific communities.

Our intent is to thaw the academic silos and offer practitioners, the public, governments, judiciary and academics more comprehensive ways to bring forward the complexities of RV. We also aim to show the many interacting variables and acknowledge similarities and differences in addressing the issue. This might promote a better understanding, and hopefully the possibility of everyone working together on this global pandemic without arguing who is impacted the most. Since this is a living book, we see it as the beginning of sharing knowledge and wish for others to contribute their understandings. You can email NEVR@kpu.ca if you wish to contribute. Also, this is not meant to be an exhaustive literature review but a synthesis of understandings from various jurisdictions and fields. We present integrated models for understandings and actions.

Integrated Models

NEVR RV Model

Current knowledge related to RV is fragmented and in silos, but it needs to be brought together. The NEVR action framework draws from multiple overlapping frameworks. Each framework is discussed and the integrated NEVR RV Model presented. It is based on the fact that no two perpetrators or survivors are the same in any given group and there are similarities within and across groups. A comprehensive understanding of the complex web of RV needs to drive laws, policies and actions and reduce the risk for all affected groups.

Multiple ways of knowing – Multiple perspectives and understandings can help illuminate health challenges such as relationship violence. We draw on the adaptation by Gurm (2013) of Carper’s (1978) and Chin & Kramer’s (2008) framework of multiple ways of knowledge and knowing. This is based on the social constructivist theory that illuminates that each individual has a unique personal understanding and view of the world based on their own experiences that are derived in multiple ways. These include empirical, ethical, personal, aesthetic, and emancipatory.

-

- Empirical. The empirical knowledge/way of knowing is based on science; it is conscious reasoning and problem-solving, predicting, explaining, and describing. Empirical knowing is used to develop formal theories and descriptions about laws, theories, and explanations that are generalizable to other situations. This is what drives the academic literature.

- Ethical knowledge/way of knowing is essentially a moral understanding of how to behave in multiple roles. This requires experiential and empirical knowledge of social norms and values, as well as ethical reasoning. Ethical knowledge can come from a professional code of ethics, social norms, or maybe philosophical positions including duty and social justice. Ethical knowledge must include judgment—that is, going beyond code to consider all actions that are deliberate and involve a decision of right and wrong. Ethical knowing involves understanding of different philosophical positions designed to deal with moral judgment and notion of service.

- Personal knowledge/way of knowing is knowledge of the self and participation in action. It is based on the assumption that interpersonal engagement and interaction must include personal experiences and understandings. In contrast to empirical knowledge, in which the researcher aims for objectivity, good personal knowledge practice acknowledges subjectivity and authenticity. The team (in this case, NEVR) is an open system that interacts and moves toward what Maslow calls self-actualization, or growth of human potential (Huitt, 2007). For NEVR, the research aims to reconcile this personal way of knowing with the role of controlling and managing the study (that is, an accepted norm or more standardized approach).

- Aesthetic knowledge/way of knowing is the art of practicing. Aesthetic knowledge recognizes that knowledge can be derived by acting—the practical skills required to work with clients. Those who are driven by aesthetic knowledge tend to draw from previous experiences, rather than empirical frameworks. It requires a deep appreciation of the context and moves beyond surface elements of the situation to a greater understanding of the whole. It may involve an intuitive, creative approach to action and decision. It is aesthetic—practical—knowledge that leads to transformation.

- Emancipatory knowledge/way of knowing is understanding that critically examines the context or the environment in which they practice, develop programmes, or decision occurs; that is, the social and political process of the organization, province or state, and country. It is about understanding both the mission and goals of agencies, as well as the social barriers or challenges involved in achieving those goals. It includes a historical understanding of those involved in partnerships (e.g., historical oppression) to better understand the multiple roles of partners. It requires facilitators and leaders with the capacity to recognize oppressive hegemonic practices as well as to recognize the changes that are required to “right the wrongs” that exist. Emancipatory knowing is developed through action with reflection (Gurm, 2013).

These multiple ways of knowing are key components in NEVR’s framework for we value all our members and their understandings and perspectives on relationship violence. While empirical knowledge provides the theories about conducting and applying knowledge, to date, there is much literature and many theoretical frameworks for why RV exists and how it is perpetuated, as well as programmes on effective prevention and intervention. These theories and programmes not always address the fact that there is great variation in RV at the group and individual levels. As such, general theories may not work in particular situations, such as when dealing with a multidisciplinary and widespread issue like RV, because collaborations by definition are not closed systems, but they are open and constantly changing.

Socio-environmental framework – As well as accepting that there are different ways of knowing, we accept the social-ecological framework for health promotion. That is, the understanding that health is a positive state defined by connectedness or relationship to one’s family/friends/community, being in control, having the ability to do things that are important or have meaning, as well as community and societal structures that support positive human development. In this approach having control is seen as a major concept for a state of well-being (Lalonde, 1974). Also, RV is defined in terms of psychosocial risk factors and socio-environmental risk conditions, such as poverty, homelessness, isolation, powerlessness, stressful environments, hazardous living and working conditions; and social factors such as race, gender, ability and normalizing and acceptance of RV by the community (Capaldi et al., 2012; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016; Kantor & Jasinski, 1998; Stith et al., 2004; Vagi et al., 2013). Part of the reason why the feminist perspective that relationship violence is a gendered issue and only exists against women has explained RV well in the past is that most societies that the theories were developed from were on the extreme spectrum of patriarchy whilst today there is a range from more equitable societies in western nations to more patriarchal societies in less developed nations.

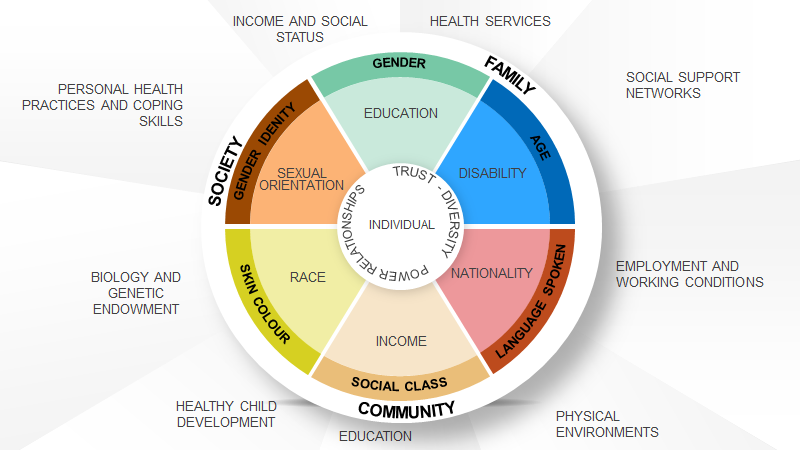

Figure 6.1 – Health Promotion Model (Government of Canada, 2001)

The socio-environmental model explains how relationship violence is a result of behaviours and social situations that occur in multiple interacting systems. It is a health promotion framework that looks at the individual, family, community and societal levels and is adopted by Health Canada (2001). The context may include demographic, neighbourhood, school or community (Capaldi et al., 2012). It looks at various elements in each system and incorporates individual and societal level theories. It indicates that health is a result between the combination or interaction of multiple factors (i.e., social determinants of health) and explains that actions need to be aimed at all systems. Social determinants that have been identified for Canadians are:

-

- Aboriginal Status

- Early Childhood Development

- Education

- Employment and working conditions

- Food insecurity

- Gender

- Health care services

- Housing

- Income and its distribution

- Social Exclusion

- Social Safety net

- Unemployment and job security

- Disability (Ability)

- Geography

- Immigrant status

- Race (Raphael, 2016; Mikkonen & Raphael, 2010)

These 16 social determinants contribute to relationship violence, and they make up the risk factors identified. How much they contribute to a particular person is unique to the individual. NEVR recognizes the broad framework for implementing the healthy public policy of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (World Health Organization [WHO], 1986) which in addition to stating that “prerequisites and prospects of health cannot be ensured by the health (or any) sector alone,” (p. 3). It calls for action by all concerned such as governments, health and other social and economic sectors, non-governmental and voluntary organizations, local authorities, industry and the media. Professional, social groups and health personnel have a major responsibility to mediate between differing interests in society for the pursuit of health (Public Health Agency of Canada, 1986, p. 3). The interventions and actions in the socio-environment model of health prevention are community development, coalition building, political action and advocacy and societal change. We have been building coalitions and this living book is another way for us to build a coalition and develop ourselves and our colleagues to engage in advocacy and social change together.

To understand the complexity of RV, we have integrated the Intersectionality and Cultural Safety frameworks because within each system (i.e., individual, family, community, sector, society) exists power and privilege and taken for granted internalized practices of power that may have been passed on for generations. Everyone within the system needs to be aware of their own social location, positionality and question received knowledge. There also needs to be an awareness of history and its impacts that are transferred through generations.

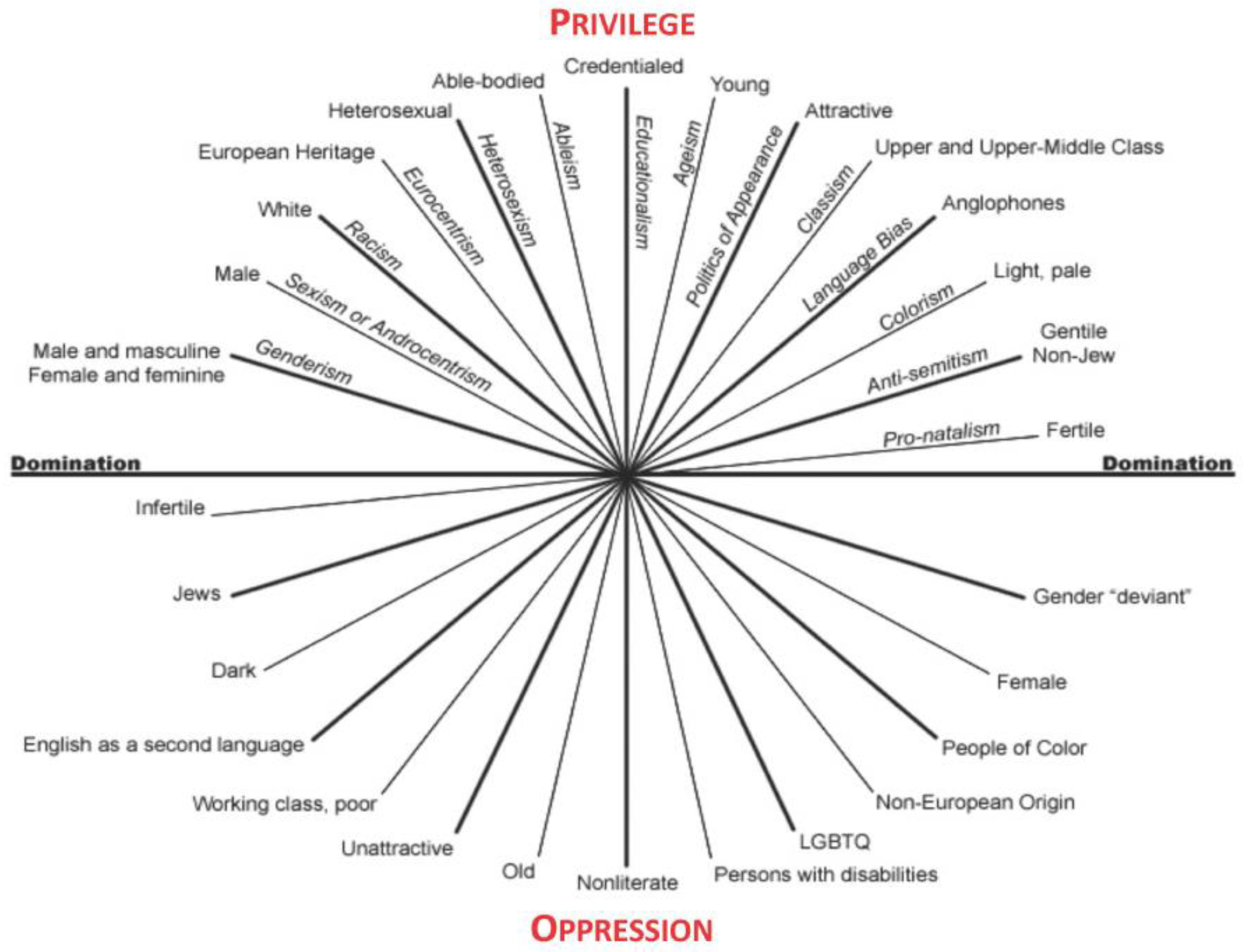

Intersectionality Theory – explains how identity, experience and positionality intersect to create oppression that underpins interactions and in turn relationship violence (Cramer & Plummer, 2009; Meyer, 2010). See the Intersecting axis of power and privilege below and place the survivor on the wheel to understand the totality of the person. Intersectionality theory explains that individuals have multiple roles and identities. Each individual life within systems of power and privilege is the sum of power/privilege in a specific situation, that may contribute to RV. Also, it illuminates the diversity of populations and individuals to help create more specific and relevant programs.

Figure 6.2 – Intersecting Axis of Power and Privilege (Roberts et al., 2019)

Within systems, the risk may be increased due to historical, political, and socioeconomic realities, and the normalization and generational transmission of violence that leads to a culture that normalizes abuse. The history and impact of experiences and the code of silence to protect the family and community all contribute to increased RV.

Racism and gender inequality through many elements like barriers to voting and denying positions of leadership to minorities and women may also contribute to RV. In addition, economic dependency, poverty, lack of parenting skills, formal education, geographic isolation, government, and historical structures in remote communities increase the risk of abuse for some groups including immigrants, refugees and Indigenous peoples (Brassard et al., 2015). A collaborative framework, as well as an intersectional approach, is part of the model. Intersectionality means utilizing the sociological insight that people are shaped by the interactions of different social concepts (i.e., all of the psychosocial risk factors and socio-environmental risk conditions above) such as race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, age and religion. They all impact a person’s positionality and either oppress or privilege them depending on accepted social norms. Also, these interactions occur within a context of connected systems, relationships and structures of power (Collins, 2015). An individual can have power and privilege in one role and be oppressed in another role. This is experienced simultaneously, and it is influenced by context. Context also determines power and privilege. Of note, the systems and power structures are of great significance, particularly regarding cultural safety.

Cultural Safety (CS) – Across Canada and in many nations around the world, there is a history of colonialism, racism and white privilege. For many years, practitioners were told to become culturally competent and many books and articles were written on how to deal with Indigenous and racialized populations. However, generalizations were published about groups leading all to believe that these groups were homogeneous. However, when generalizations are applied to every single person of a given group, it leads to stereotyping. Cultural safety recognizes that stereotypes and negative attitudes exist in scientific literature, which carries into practice (Ramsden, 1990). This may explain why oppressed people feel that the system and its services revictimize them. This results in many individuals not having a sense of cultural safety. When working with individuals in Canada, a diverse population with many cultural backgrounds, cultural safety is paramount, as misunderstandings can reduce the efficacy of care offered. When working to address RV, an issue that is pervasive and normalized in different ways across cultures, it is more important still. This recognition of normalized as taken for granted practices that overlap with the concept of emancipatory knowing. Also, it is widely accepted that knowledge of culture is an important part of effective therapeutic communication that can improve health outcomes (Kreps, 2006).

Cultural safety accepts that all individuals belong to a culture, and unequal power relations and racism exist within and between cultural groups at the family, community, and societal level. In nursing education, cultural safety was first introduced by Irahapeti Ramsden, a Maori nurse in her doctoral dissertation, to address the historical oppressions that have led to higher rates of illness in the Maori population. It is based on the premise that historical, social and political processes have a lasting influence on marginalized groups (e.g., the Maori in New Zealand, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in Canada), and must be recognized (Ramsden, 2002). Cultural safety examines prejudice, power and bicultural relations. It can be applied to any person or group that differs on any axis of privilege, domination and oppression (age, ability, ethnicity, sexual orientation, migrant status, religious belief, socioeconomic status, education, etc.). It is about the unique bicultural relationship of two people and the focus is on the service provider/employer/educator/boss (privileged person) to create a trusting environment and equal partnership with the person who is in an oppressed position. Only the recipient (the oppressed person) can decide if cultural safety has been achieved. The focus is on the one with the power to reflect on their power and assumptions in order not to stereotype but listen to and understand the other person. This can also be applied to multicultural relationships with three or more people.

Cultural safety is practiced through cultural humility and the following occurs:

- Service providers become curious and reflective practitioners

- Listen to understand

- Practitioners reflect on their own biases and confront their prejudices

- Communicate in a respectful manner that recognizes historical and systematic (organizational/societal) oppression

- Create an equal partnership between those who are communicating with each other

- Create a trusting environment

Practicing cultural safety ensures that health care staff (all service providers) are respectful of nationality, culture, age, sex, sexuality, political and religious beliefs, and the position of their clients. Awareness of these intersecting systems has the potential (consciously or unconsciously) to influence the power balance between clinicians (service providers) and patients (recipients of care), as well as between colleagues. In nursing, cultural safety is understood to mean there is no damage or harm by interactions between people, and that dignity and respect are maintained for all parties in an interaction (College of Registered Nurses of British Columbia [CRNBC], 2010). Creating a culturally safe environment requires practitioners to have cultural humility. It requires self-reflection on personal oppression and privilege as well as identification of biases and to create respectful partnerships based on trust. It is about creating equity in partnerships that is consistent with the concept of social justice.

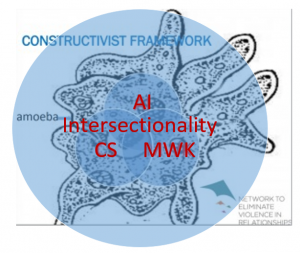

Figure 6.3 – NEVR Relationship Violence Model

Using these overlapping frameworks, the high-risk societal conditions are targeted, and political and economic policies are introduced at the community level. We work with multiple stakeholders to address these societal conditions and reject the normalizing of relationship violence. Interventions are aimed at family, school, work, communities and society. Indeed, the benefit of viewing relationship violence from a socio-environment perspective is that it allows RV to be targeted at a family and community level, rather than an individual level. It allows for looking at circumstances and events rather than blaming individuals. The NEVR RV Model is used to understand the complex health global epidemic of RV. It shows that RV results from socio-environmental factors as well as individual choices. These choices are constrained by the individual’s diversity and power within relationships and structures that operate within taken for granted practices. In this model, we are aware of these constraints so try to create equal power, engage in a culturally safe manner to create trust. In order to collaborate and work with others, we add the change model of Appreciative Inquiry.

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) – Cooperrider & Srivastva (1987) describe Appreciative Inquiry (AI) as a process used to develop positive change in organizations. Additionally, AI is a form of action research that attempts to create new theories, ideas, and images that aid in the developmental change of a system. It is a strengths-based approach that allows for social change. Instead of viewing clients, families, and organizations as machines, it views them as organisms—that is, adaptive, and above all, interactive within themselves and with other organisms (systems). It is believed that they are all open systems. It overlaps with all the previous frameworks discussed for the concept of social construction is inherent in the philosophy of AI. “Reality” is created by those in the system; our ability to change is limited by collective will and imagination. To effect change from an AI perspective, it is imperative to be respectful of the experiences of the group members. AI does not view a problem as a problem, per se, and does not use a traditional problem-solving approach. Instead, it looks at the desire for something—it asks people to look into their past, locate how they felt, recall what they did when they experienced a positive state, and to amplify that in the present (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987). For RV, this means asking clients, stakeholders, and communities to focus on their feelings when they are in control, free of relationship violence, and healthy, and to ask them to identify what they need currently to have those feelings and make that change. In these cases, images and language must be used with intentionality and in programs on healthy relationships, parenting, employment skills, etc.

Figure 6.4 – NEVR Collaboration and Action Framework

At all meetings, the model on the left (Figure 6.4) is integrated by NEVR. In the constructivist framework, Cultural Safety (CS), appreciative inquiry (AI), Multiple ways of knowing (MWK) and Intersectionality theory interact and are constantly changing to address RV. We imagine NEVR similar to an amoeba system. Just like an amoeba changes its shape, so does NEVR because the committee is constantly evolving as it interacts with members (i.e., internal environment) and organizations/policies/law/allies (external environment). Each member has multiple roles and identities that interact to provide innovative perspectives and understanding (intersectionality). The committee values all members’ ideas because it believes in multiple ways of knowing (MWK) creating equal power and trust which in turn results in cultural safety (CS). NEVR focuses on its mission (i.e., dream) of eliminating relationship violence and not on the statistics of today (AI). The facilitator ensures each individual at the meeting is respected and provided an equal opportunity to voice their opinion, and the decisions are made from an inclusion perspective. From the cultural safety perspective when working with survivors, one of the goals is to ensure no harm is done to the service provider, and their specific current situation and any historical oppression are considered. Although originally developed to work with individuals, cultural safety applies to groups, organizations, and communities. Emphasis is placed on the desires of the service provider, and where they are positioned in terms of family, workplace, and community roles and dynamics. Also, it is acknowledged that interactions are dynamic constantly change like the amoeba in the figure. It is recommended that this approach be carried out in all collaborations between individuals and organizations and when working with survivors and perpetrators.

At all meetings, the model on the left (Figure 6.4) is integrated by NEVR. In the constructivist framework, Cultural Safety (CS), appreciative inquiry (AI), Multiple ways of knowing (MWK) and Intersectionality theory interact and are constantly changing to address RV. We imagine NEVR similar to an amoeba system. Just like an amoeba changes its shape, so does NEVR because the committee is constantly evolving as it interacts with members (i.e., internal environment) and organizations/policies/law/allies (external environment). Each member has multiple roles and identities that interact to provide innovative perspectives and understanding (intersectionality). The committee values all members’ ideas because it believes in multiple ways of knowing (MWK) creating equal power and trust which in turn results in cultural safety (CS). NEVR focuses on its mission (i.e., dream) of eliminating relationship violence and not on the statistics of today (AI). The facilitator ensures each individual at the meeting is respected and provided an equal opportunity to voice their opinion, and the decisions are made from an inclusion perspective. From the cultural safety perspective when working with survivors, one of the goals is to ensure no harm is done to the service provider, and their specific current situation and any historical oppression are considered. Although originally developed to work with individuals, cultural safety applies to groups, organizations, and communities. Emphasis is placed on the desires of the service provider, and where they are positioned in terms of family, workplace, and community roles and dynamics. Also, it is acknowledged that interactions are dynamic constantly change like the amoeba in the figure. It is recommended that this approach be carried out in all collaborations between individuals and organizations and when working with survivors and perpetrators.

Risk Factors for RV

The world is becoming smaller and knowledge is shared freely through the internet. We know that relationship violence occurs from conception to death and impacts all genders with a consensus that some groups are at greater risk than others. Identifying risk factors allows for the development of appropriate services and programs in order to safely plan programs to prevent abuse. Risk factors are a combination of environmental and social conditions and individual’s biology/genetics).

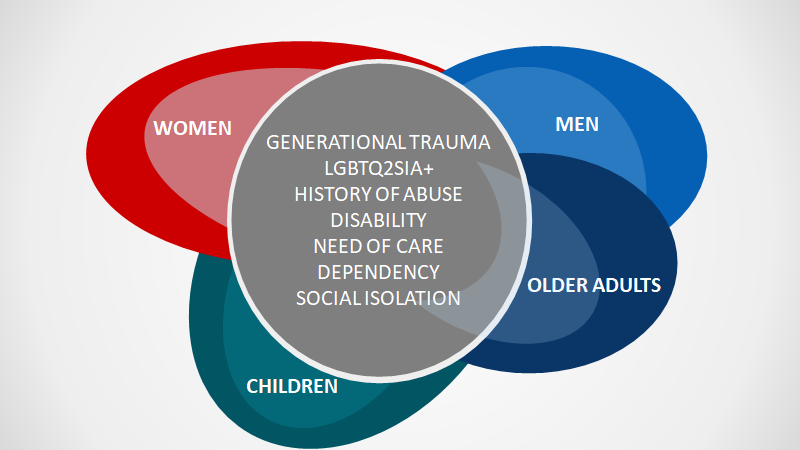

In our literature review of Canadian studies, certain populations are identified as more vulnerable than the general population to RV; for instance, Indigenous, Northern and Remote Communities, children, older women, LGBQT2SIA+, immigrants and refugees, those who live with an impairment or disability (Jeffrey et al., 2018), low socioeconomic status (SES), low education, dependency, low control, oppression, witnessed abuse, suffered abuse or maltreatment (CDC, 2019). As well, the most severe form of RV like death is 4.5 times higher among women versus men. In addition, children considered one of the most vulnerable groups, face an extremely high risk of death, for they may be killed in a variety of situations including revenge or crossfire (Jeffrey et al., 2018). Although some groups might show higher risk depending on social situations, there is a great overlap in risk factors between groups. While much of the literature and our later chapters focus on each group across the lifespan separately, in this chapter we focus on bringing together the risks and successful initiatives and apply an integrative model. See chapter 15 for details about RV against women, chapter 16 for children, chapter 17 older adults, chapter 18 for men, chapter 19 for Indigenous populations, chapter 20 for LGBQT2SIA+, chapter 21 for immigrants and refugees, and chapter 22 for workplace violence.

Figure 6.5 – Common Risk Factors of RV among Children, Women, Men and Older Adults (CDC, 2014; Renzetti, 1992; Stith et al., 2004)

We know that for all age groups the risk factors for being abused are disability (cognitive or physical impairment), LGBQT2SIA+ groups, need of care, dependency, social isolation (CDC, 2014) and intergenerational trauma (Franco, 2020; Stith et al., 2004). Notice there are overlapping risk factors across groups. Substance use, dependency, intergenerational trauma, relationship satisfaction (Renzetti, 1992; Stith et al., 2004) jealousy, anger, and/or control (Graham-Kevan & Archer, 2005) are risk factors for all adults (men, women, older adults). For example, young age is a risk factor for women and men and some authors believe abuse peaks at adolescents (Kim et al., 2008; Nocentini et al., 2010). Table 6.1 is created from available data on risk factors for different groups.

Table 6.1 – Comparison of RV Risk Factors among Groups (Derived from: CDC, 2014; Graham-Kevan & Archer, 2005; Kim et al., 2008; Nocentini et al., 2010; Renzetti, 1992; Stith et al., 2004)

| Cohort | Young Age | Low Level of Education | Low Income | Low Social Status | Substance use | Indigenous | Relationship Satisfaction | Jealousy |

| Children & Youth | peaks at adolescents | inconsistent data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | inconsistent data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Older Adults | not applicable | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cohort | Need of support | Control | High level of financial dependency | Lack of social support | Lack of formal support | History of violence in the family | Anger & hostility |

| Children & Youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Men | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Older Adults | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Besides risk factors for victims/targets, there are risk factors for perpetrators to commit relationship violence. There are a number of already tested tools that are used to assess the risk to become an offender of RV. See chapter 13 on measurement tools to assess risk. The general risk factors for perpetration of RV that we can find data on are listed below in table 6.2 (CDC, 2020a; CDC, 2020b, CDC, 2020c).

Table 6.2 – Relationship Violence Risk of Perpetration across Groups (Derived from CDC, 2020a, b, and c)

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Parents lack understanding of children’s needs | x | |||

| Experiencing or having poor parenting skills | x | x | ||

| Substance abuse | x | x | x | x |

| Mental health issues | x | x | x | x |

| Young age | x | x | ||

| Single parenthood | x | |||

| Large number of dependent children | x | |||

| Nonbiological parent | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Emotions & views that justify maltreatment behaviours | x | x | x | |

| Low income | x | x | x | |

| Low education | x | x | x | |

| Exposure to abuse early in life | x | x | x | x |

| Attention deficits and learning disorders | x | |||

| Low IQ | x | x | ||

| Inadequate coping skills | x | x | ||

| Deficits in social cognitive or information-processing | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| x | x | x | ||

| Low self-esteem | x | |||

| Lack of healthy social problem social skills | x | x | ||

| History of experiencing physical discipline as a child | x | x | ||

| Financial dependency | x | x | ||

| Weak social policies | x | |||

| Few friends & isolation | x | x | x | |

| Unemployment | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Strict views about gender roles | x | |||

| Desire of power and control | x | |||

| Conflicts in the family | x | x | ||

| Unplanned pregnancy | x | |||

| Poor caregiving training | x | |||

| Lack of social support | x | |||

| Lack of formal support | x | x | ||

| Emotional dependency | x | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Inadequate coping skills | x | x | x | |

| Poor and negative interactions | x | x | ||

| Community violence | x | x | ||

| Authoritarian child-rearing attitudes | x | |||

| Inconsistent disciplinary practices | x | |||

| Low parental involvement & monitoring of children | x | |||

| Low emotional attachment | x | |||

| Poor family functioning | x | x | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Association with antisocial or aggressive peers | x | x | ||

| Involvement with gangs | x | |||

| Social rejection by peers | x | |||

| Lack of involvement in conventional activities | x | |||

| Poor academic performance & School failure | x | x | ||

| Jealousy & possessiveness | x | |||

| Poverty | x | x | ||

| Cultural norms that support aggression | x |

| Adult Against Children | Children Against Children | Adult Partners | Against Older Adults | |

| Low level of community participation | x | x | x | |

| Socially disorganized neighbourhoods | x | x | ||

| Economic stress in the family | x | x | ||

| Lack of economic opportunities | x | |||

| Hostility towards women | x | |||

| Income inequality | x | |||

| Assuming care-giving responsibilities at early age | x | x | x | |

| Family disruption | x | x | x |

Several overlapping frameworks that help address RV have been outlined as part of the NEVR model. Also the risk factors that are common between groups identified. It is important to note that risk factors are just that, they are not causal.

References

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651-680.

Archer, J. (2006). Cross-cultural difference in physical aggression between partners: A social-role analysis Personality and Social Psychology, 9(3). 212-230 doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2

Brassard, R., Montminy, L., Bergeron, A. S., & Sosa-Sanchez, I. A. (2015). Application of intersectional analysis to data on domestic violence against aboriginal women living in remote communities in the province of Quebec. Aboriginal Policy Studies, 4(1), 3-23. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/aps/index.php/aps/article/ view/20894/pdf_31

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231-280.

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Carper, B. (1978). Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. Advances in Nursing Science, 1(1), 13-23. doi:10.1097/00012272-197810000-00004

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Connecting the dots: An overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/connecting_the_dots-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Preventing multiple forms of violence: A strategic vision for connecting the dots. Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). https://www.cdc.gov/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Prevention strategies. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Risk and protective factors: Child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020c). Risk and protective factors. Elder abuse. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/riskprotectivefactors.html

Chinn, P. L., & Kramer, M. K. (2008). Integrated theory and knowledge development in nursing. Mosby Elsevier.

College of Registered Nurses of British Columbia – CRNBC. (2010). Entry-level competencies of a new graduate. http ://www.crnbc.ca/Registration/Lists/Registratio nResources/375CompetenciesEntrylevelRN.pdf

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 4(1), 1-20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Cooperrider, D. L., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 1, 129-169. doi 10.1108/s1475-9152(2013)0000004001

Cramer, E. P., & Plummer, S. B. (2009). People of color with disabilities: Intersectionality as a framework for analyzing intimate partner violence in social, historical, and political contexts. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(2), 162-181.

Dixon, L., & Graham-Kevan, N. (2011). Understanding the nature and etiology of intimate partner violence and implications for practice and policy. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1145-1155. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.00

Dobash, R., & Dobash, R. (1980), Violence Against Wives. Open Books.

Dobash R.P., & Dobash R.E. (2004) Women’s violence to men in intimate relationships: Working on a puzzle. Br J Criminol 44:324–349.

Franco, F. (2020). How intergenerational trauma impacts families. Psyc Central. https://psychcentral.com/lib/how-intergenerational-trauma-impacts-families/

Government of Canada. (2001). Health promotion model: An integrated model of population health and health promotion. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-promotion-integrated-model-population-health-health-promotion/developing-population-health-promotion-model.html

Graham-Kevan, N., & Archer, J. (2005). Investigating three explanations of women’s relationship aggression. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(3), 270-277.

Gurm, B. (2013). When love hurts. NEVR Conference. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Health Canada. (2001). An integrated model of population health and health promotion. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-promotion-integrated-model-population-health-health-promotion/why-are-we-doing-this.html

Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/regsys/maslow.html

Iliadis, M. (2019). Deakin researcher: Violence against women still a national emergency. Deakin University. https://www.deakin.edu.au/about-deakin/media-releases/articles/deakin-researcher-violence-against-women-still-a-national-emergency

Jeffrey, N., Fairbairn, J., Campbell, M., Dawson, M., Jaffe, P., & Straatman, A-L. (2018). Canadian domestic homicide prevention initiative with vulnerable populations (CDHPIVP): Literature review on risk assessment, risk management and safety planning. Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. http://cdhpi.ca/literature-review-report#sem

Jones, R. J. N. (2018). Investigating the relationship between approval, and experiences of physical violence and controlling behaviours in heterosexual intimate relationships. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Victoria University of Wellington.

Kantor, G. K., & Jasinski, J. L. (1998). Dynamics and risk factors in partner violence. Sage Publications, Inc.

Kim, H. K., Laurent, H. K., Capaldi, D. M., & Feingold, A. (2008). Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1169–1187.

Kreps, G. L. (2006). Communication and racial inequities in health care. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(6), 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205283800

Lalonde, M. (1974). A new perspective on the health of Canadians. Minister of Supply and Services Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/pdf/perspect-eng.pdf

Lien, M., I., & Lorentzenm J. (2019). Men’s experiences of violence in intimate relationships. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03994-3

Meyer, D. (2010). Evaluating the severity of hate-motivated violence: Intersectional differences among LGBT hate crime victims. Sociology, 44(5), 980-995.

Mikkonen, J., & Raphael, D. (2010). Social determinants of health: The Canadian facts. York University School of Health Policy and Management.

Nocentini, A., Menesini, E., & Pastorelli, C. (2010). Physical dating aggression growth during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 353–365

Public Health Agency of Canada. (1986). Achieving Health for All: A framework for health promotion. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/achieving-health-framework-health-promotion.html

Ramsden, I. (1990). Cultural safety. New Zealand Nursing Journal, 83(11), 18-19.

Ramsden, I.M. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu: A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing.

Raphael, D. (2016). Social determinants of health: Canadian Perspectives, 3, 3-31.

Renzetti, C. M. (1992). Violent betrayal: Partner abuse in lesbian relationships. Sage Publications.

Ristock, J. L. (2003). Exploring dynamics of abusive lesbian relationships: Preliminary analysis of a multisite, qualitative study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(3),4, 329-341

Roberts, J.D., Mandic, S., Fryer, C.S., Brachman, M.L., & Ray, R. (2019). Between privilege and oppression: An intersectional analysis of active transportation experiences among Washington D.C. area youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 16, 1313. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/8/1313/htm

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex Couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Stith, S. M., Smith, D. B., Penn, C. E., Ward, D. B., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 10, 65-98.

Straus, M., & Gelles, R. (1986). Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48(3), 465-479. doi:10.2307/352033

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

Vagi, K.J., Rothman, E.F., Laztman, N.E., Tharp, A.T., Hall, D.M., & Breiding, M.J. (2013). Beyond correlates: A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(4), 633–49. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7

Walters, M., Chen, J., & Brieding, M. (2013). The National intimate partner and sexual violence Survey: 2010 findings on victimisation by sexual orientation. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf

World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index2.html