Chapter 15: Relationship violence against women commonly called IPV or domestic violence

Balbir Gurm and Glaucia Salgado

Key Messages

- There are many theories that have been presented over the years to explain relationship violence, including psychological, psychopathological, sociological, structural, and others. We accept the socio-environmental model, as it draws on them all.

- The “cycle of abuse” and “power and control” wheel are among the most common frameworks to understand the interplay of violence in relationships.

- Other researchers have gone so far as to classify the types of abuse that are most common as intimate terrorism, violent resistance, mutual violent resistance and situational couple violence.

- There is a debate regarding the gendered nature of violence, with the feminist school of thought arguing that it is predominantly men who perpetrate violence. However, recent discussions highlight gender symmetry – see chapter 5.

- While Canadian statistics support the idea of gender symmetry on the lower end of the violence continuum, they also show that women are more likely to experience violence more severely and frequently than men. Challenges in reporting make it difficult to understand this phenomenon with accuracy.

- NEVR’s position is not to argue about who is the most victimized, but to work across agencies to reduce relationship violence across the lifespan. The work of NEVR continues to promote collaborative practices and integration with local and provincial government partners.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus) (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollè et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death.

RV Against Women

In this chapter, we focus on RV against women. Here is a video on the definition of RV, commonly referred to as intimate partner violence or domestic violence when it is against adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018). Click here to listen to a survivor talk about her experience (Learning to End Abuse, 2017).

Relationship violence against women is a complex and multi-dimensional issue. Besides affecting women and societies worldwide, it is considered a significant public health problem with short and long-term consequences (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). Social structural issues related to acceptance and legitimization of violence against women are critical factors related to the pervasiveness of this crime (Gonzáles, 2017; Herrero et al., 2017). Abuse against women encompasses a range of violent behaviours that are multifaceted in its forms and aetiologia. From issues correlated to geographical and cultural norms to the manifestation of unequal power in many societies, generally, such actions refer to physical and psychological violence, and sexual abuse (United Nations [UN], 1993; WHO, 2017). The literature tends to use the terms abuse, violence and maltreatment interchangeably when referring to any subtype of abuse against women. Similarly, most literature refers to these terminologies when addressing violence in heterosexual relationships. All forms of abuse against women have significant negative results on the overall health and the life of women. Largely, the most prevalent form of violence against women is sexual abuse, and it is often differentiated from physical abuse. One measure of violence used by many governments, the Conflict Tactic Scale, does not consider sexual abuse as an act of violence – see chapter 5. Besides physical, psychological and sexual abuse, the literature refers to stalking behaviour, economic and power inequalities as critical forms of violence against women (Breiding, 2014; Carter, 2015; Postmus et al., 2016).

It is estimated that 1 in 3 women worldwide has experienced some form of violence (WHO, 2017). In Canada, the rates are similar (28%) and greater among Aboriginal, immigrant women and those with disabilities (see chapter 5). For the most part, statistics are primarily based on physical and sexual violence, partly because RV is underreported (see chapter 5) and partly because prosecutions mainly occur for these two forms of violence. Globally, 38% of murders against women are committed by their male partners and women are twice as likely as men to experience sexual assault, being beaten, choked or threatened with a gun or a knife (WHO, 2017). Also, women who identify themselves as lesbian or bisexual are at increased risk compared to heterosexual women, 11% versus 3%, respectively (Ibrahim, 2019), see chapter 20.

See percentage information of cases below:

-

-

- Women and girls between the ages of 15 to 24 years old represent 67% of all cases

- 79% of police-reported relationship violence is against women and girls (Burczycka & Conroy, 2018)

- The homicide rate is four times greater among women versus men (David, 2017).

- Pregnant women have an increased risk of relationship violence (Baird, 2015; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006)

- Indigenous women are more vulnerable to experience physical abuse (60%) than non-aboriginal women, 60% versus 41%, respectively (Boyce, 2016)

-

There is overlap in risk factors, signs, symptoms and treatment options for all those impacted by RV regardless of age, sexual orientation, race, economic status, etc (see chapter 5).

Out of all forms of RV, violence against women and girls has been studied the most in Canada and around the world. Most of the literature has normalized heterosexual relationships and identified the male as the offender, indicating that this issue is being addressed, at least in many studies, as a gender-based approach. However, as shown in chapter 18, RV can be perpetrated by both men and women.

RV can also occur in non-heterosexual relationships (LGBTQ2SIA+). LGBTQ2SIA+ is the most recent term being used in Canada and in the North American context. It is defined as follows: L=Lesbian, G=Gay, B=Bisexual, T=Transgender, Q=Queer or Questioning, 2S = Two-Sprit, I=Intersex and A=Asexual. RV occurs within a social context that has hegemonic practices that may be passed on for generations. It can span the entire age spectrum. This chapter focuses on RV against those who identify as female or women. There is a separate chapter for children and girls are included there. Also, a chapter each for older adults, LGBTQ2SIA+, immigrant and refugee communities and Indigenous populations.

Stalking

Besides the most discussed types of relationship violence (i.e., physical, psychological and sexual abuse), the literature refers to stalking behaviour, economic and power inequalities as critical forms of violence against women (Breiding, 2014; Postmus et al., 2016, Carter, 2015). Stalking—also called criminal harassment—refers to unwanted surveillance. These behaviours occur as repeated episodes of being called, watched, followed, receiving unwanted gifts and threatening messages. To learn more and hear a personal account, click here (Outside of the Shadows, 2017). Although stalking has been categorized as a distinct form of abuse, it tends to occur concomitantly with physical. However, stalking, considered a crime in Canada and the US, is not perceived as a criminal offence in many countries due to the lack of proper legislation to address these behaviours (Department of Justice Canada, 2003; WHO, 2017). Despite Canada having established stalking as a crime – declaring even the month of January as the Stalking Awareness Month – there are critical gaps in criminal justice even in countries such as Canada that recognize stalking as a crime (Statistics Canada, 2018; WHO, 2017). Canadian statistics reveal that women who report stalking to the police “did not see tangible justice systems outcome to ensure protection from the stalker” (Statistics Canada, 2018, p. 24). In the US, criminal justice requires that at least two or more different events of stalking have occurred to establish criminal stalking behaviour (Office for Victims of Crime [OVC], 2018). However, there are extreme cases, in which one occurrence is enough to trigger harmful results (National Center for Victims of Crime [NCVC], 2011).

Economic Abuse and Power

When verifying data on economic abuse and power, an analysis of 4 articles suggests that power inequalities and economic abuse are intrinsically connected. Historically, men are more likely to hold high social positions, and economic and political influence, which in turn generates a relationship between power and oppression. For those “in charge”, this interplay means having control over resources and choices while labelling women as inferior and subordinate. As a result, this situation limits access to education and work opportunities that consequently hinder women’s chances of self-efficacy and enjoying control over their own lives (Anderson et al., 2010; Barner et al., 2014; Sanders, 2015; Shtybel & Artemenko, 2016). Congruently, studies explaining the high incidence of violence against women indicate the critical role of the patriarchal system affecting behaviours and promoting a society that consents to unequal relations of power and privileges (Carter, 2015). Furthermore, social norms, values and roles are critical to explaining violence against women (Hunnicutt, 2009; Yllo & Straus, 2017).

Health Impacts

As incidents, prevalence rates and types of abuse against women become more apparent, its health consequences are also better understood. Flury and Nyberg (2010) suggest that women who have experienced violence are more likely to show poor mental and physical health and vulnerability to diseases. Health challenges that result from RV impact the heart, digestive, reproductive, muscle and bones and nervous systems that may lead to chronic physical and psychological conditions, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety (CDC, 2003). Besides these overall health outcomes, women face a lack of opportunities to improve their social condition leading to the perpetuation of low socio-economic status and victimization (Dillon et al., 2013).

Attitude

Although there are several studies on violence against women, systematic reviews indicate that intimate partner violence towards women is still poorly understood. After analyzes of 62 articles published between 2000 and 2018, a study by Gracia and colleagues (2020) indicates that intimate partner violence towards women correlated with three main areas – attitudes, socio-demographic attributes, and psychological variables. Although all these three areas were critical, studies included in the review indicated that attitudes had the strongest correlation with IPV towards women. Among attitudes described in the studies were legitimation and acceptability of violence, attitudes related to intervention and perception of violence severity. Even though attitudes had the strongest correlation, only a small percentage of studies (9.7%) evaluated change in attitudes after an intervention program (Gracia et al., 2020). This suggests that there may be a need to focus on these types of behaviours and how to change them.

Understandings

Most of the literature on RV against women is based on feminist theories and approaches. Also, early theories that explained relationship violence against women were generally based on heterosexual relationships and psychological frameworks. In the mid-1900s, wife-beating was considered a symptom of a dysfunctional relationship by a disturbed spouse. These theories focused on personality disorders and dysfunction secondary to social factors. However, these views used to explain relationship violence were challenged because they did not hold the dominant male accountable, blamed the victim and positioned RV as simply a family matter.

A student of famous psychologist Sigmund Freud, Helene Deutsch, in her article The Significance of Masochism in the Mental Life of Women, Part I: ‘Feminine’ Masochism and its Relation to Frigidit (1929) stated that women enjoyed masochistic sex putting the blame on the female victims for sexual violence. The feminist movement of the 1970s (most writings came from those known as Radical feminists) challenged these positions as did family theorists.

While Walker (1979) explained RV with the term “battered women syndrome”, suggesting that some women have low self-esteem, feelings of guilt, and traditional views about marriage and gender that lead to learned helplessness. Women may develop a state of consciousness in which they believe that no matter what they do, they cannot change their situations. As well, in cultures, at present or historically, women were and still are taught to obey men.

From father’s house to a husband’s house to a grave that still might not be her own, a woman acquiesces to male authority in order to gain some protection from male violence. She confirms, in order to be as safe as she can be. (Dworkin, 1983, p. 14)

This socialization continues from generation to generation through societal and government processes (Foucault, 1977). Social structural issues linked to acceptance and legitimization of violence against women are critical factors related to the pervasiveness of this crime (Gonzáles, 2017; Herrero et al., 2017).

Relationship violence can happen to women of any age, class or race. Walker (1979) was one of the first to debunk that only certain types of women suffered relationship violence. This led us to the Duluth Model and the Power and Control Wheel and the Cycle of Abuse used by many transition homes and service agencies today. In the cycle of abuse, abusers act out and hit their victims, then they try to rationalize and justify their actions and the survivor may blame themselves for the abuse. Once the survivor accepts the story of the abuser the pretend normal cycle starts, where the couple proceeds as if everything is fine. It is calm and peaceful until the tension starts to build-up overstresses or conflicts and the abuser starts to feel helpless and may start calling the survivor names. Then the stress and powerlessness are so great, it leads to an acute episode of severe violence (act out). The cycle may last hours or weeks, but it tends to get shorter over time and acute violence becomes more frequent.

Figure 15.1 – Cycle of Abuse

Power and Control

Gendered violence is the dominant model that is used in Canada, and it posited that men use a variety of control tactics on their partners and that intimate partner violence should mainly be concerned about males perpetrating violence towards females (Dobash & Dobash, 2004). The Power and Control Wheel (below) shows a variety of tactics that are used by partners. The Duluth Model is based on the fact that there are power relationships, and these power relationships are used to control behaviour (Pence, 2017). The Duluth Model of Intervention can be found here.

Figure 15.2 – Power and Control (National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence, n.d.)

The power and control wheel explains the tactics that abusers may use to keep power and control in a relationship. Listen to YouTube videos on the Power and Control wheel. For the overview, video click here. From this site you can also access a YouTube video on each of the tactics on the wheel, using coercion and threats, using intimidation, using emotional abuse, using isolation, denying, minimizing & blaming, using children, using privilege and using economic abuse.

The Duluth Model requires agencies to work together under 4 principles:

1. Change will be required at the basic infrastructure levels of the multiple agencies involved in case processing. Workers must be coordinated in ways that enhance their capacity to protect victims and must comply fully with inter-agency agreements. Participating agencies must work cooperatively on examining, adjusting and standardizing practices by making changes in eight core methods of coordinating workers’ actions on a case. This involves:

a. Identifying each agency’s mission, purpose and specific function or task at each point of intervention in these cases.

b. Crafting policies guiding each point of intervention.

c. Providing administrative tools that guide individual practitioners in carrying out their duties. (e.g. 911 computer screens, specially crafted police report formats, D.V. appropriate pre-sentence investigation formats; education and counselling curricula designed for abusers).

d. Creating a system that links practitioners to each other so that each practitioner is positioned to act in ways that assist subsequent interveners in their interventions.

e. Adopting inter-agency systems of accountability, including; an inter-agency tracking and information sharing system; periodic evaluations of aspects of the model; bi-monthly inter-agency meetings to identify, analyze and resolve systemic problems in the handling of cases; accountability clauses in written policies.

f. Establishing a cooperative plan to seek appropriate resources.

g. Reaching agreements on operative assumptions, theories and concepts to be embedded in written policies and administrative practices.

h. Developing and delivering training across agencies on policies procedures and concepts.

2. The overall strategy must be victim-safety centred. There is an important role for independent victim advocacy services and rehabilitation programming for offenders. Small independent monitoring and coordinating organizations should be set up to coordinate workgroups, operate the tracking system, and help coordinate periodic evaluations and research projects. Victim advocacy organizations should be central in all aspects of designing intervention strategies.

3. Agencies must participate as collaborating partners. Each agency agrees to identify, analyze, and find solutions to any ways in which their practices might compromise the collective intervention goals. Small ad hoc problem-solving groups, training committees, evaluation projects, and regular meetings are used to coordinate interventions. These working groups are typically facilitated by DAIP staff but, when appropriate, maybe lead by another participating agency.

4. Abusers must be consistently held accountable for their use of violence. Effective intervention requires a clear and consistent response by police and the courts to initial and repeated acts of abuse. These include:

a. Mandatory arrest for primary aggressors;

b. Emergency housing, education groups and advocacy for victims;

c. Evidenced-based prosecution of cases;

d. Jail sentences in which offenders receive increasingly harsh penalties for repeated acts of aggression;

e. The use of court-ordered educational groups for men who batter; and,

f. The use of a coordinating organization (DAIP) to track offenders, ensure that recurrent offenders or those in non-compliance do not fall through the cracks and that victim-safety is central to the response (Pence, n.d.).

Johnson (2011) questioned that males are always the ones that exert power and control or that violence is equal between different sexes. Using the Duluth model and the power and control wheel, they created 4 categories below. These categories move RV from thinking that males perpetrate violence against females to an understanding that RV is a result of the environment created by the interactions and history of the partners involved in the relationship.

-

- Intimate terrorism – The partner uses violence for general control. Involves the combination of physical and/or sexual violence with a variety of non-violent control tactics, such as economic abuse, emotional abuse, the use of children, threats and intimidation, the invocation of male privilege, constant monitoring, blaming the victim, threats to report to immigration authorities, or threats to “out”(to make public an aspect of identity or experience, such as sexuality) a person to work or family. There is a connection between offenders that have suffered violence as children and their chances of perpetrating violence; however, the vast majority of people abused as children do not grow up to become abusers.

- Violent resistance – The perpetrator uses violence for general control and the partner responds with their own violence. Some women respond to violence with their own violence. Others do not think they have any hope of winning and may kill their partners.

- Situational couple violence – The perpetrator is violent (the partner may be too) but neither uses general control over the other. It is a situation or incident that happens that brings the violence to happen a minor incident 40% of the time that leads to arguments, aggression and then violence. It is believed to be about the same between men and women.

- Mutual violent resistance – Both members of the couple are both violent and controlling (Johnson, 2010).

Policies and Processes

Most of the research and scholarship in Western countries is based on the feminist perspective or gender-based violence perspective that is situated in a patriarchal society assuming that violence is perpetrated by males against females. This scholarship has been effective, for it has brought gender issues to the attention of governments and been successful at decreasing the gender gap by advocating for policies and practices. For instance, Canada has mandatory arrest and prosecution policies, but this solution remains divisive. Those who support the prosecution policies against violence state that it protects the women and it holds the offender accountable. However, those who disagree with these policies state that they do not deter relationship violence and may, in fact, increase it, because it teaches offenders how to not get caught. But has it worked? In the early days of this law, most families did not want convictions but wanted help to stop violence (Houston, 2014). This is similar to today. For instance, when RV is discussed on South Asian radio stations in BC, women call in and state: “I just want the police to come and stop the violence but I do not want my partner to be charged and sent to jail.” This sentiment is similar to what the police tell us. They may be called in several times to the same household, but each time the woman states she does not want charges, only for the violence to stop.

Besides court processes, there are alternative dispute resolution processes (see chapter 8). The most common are mediation and healing/peace/reconciliation circles and sentencing circles. These processes involve the partners dialoguing with each other (mediation) and also dialoguing with the community (circles). A combination of processes may be used. The goal of court processes is to provide offender accountability and safety for the survivor. The primary goal of mediation and circles is to facilitate healing. This may be an approach that could be expanded.

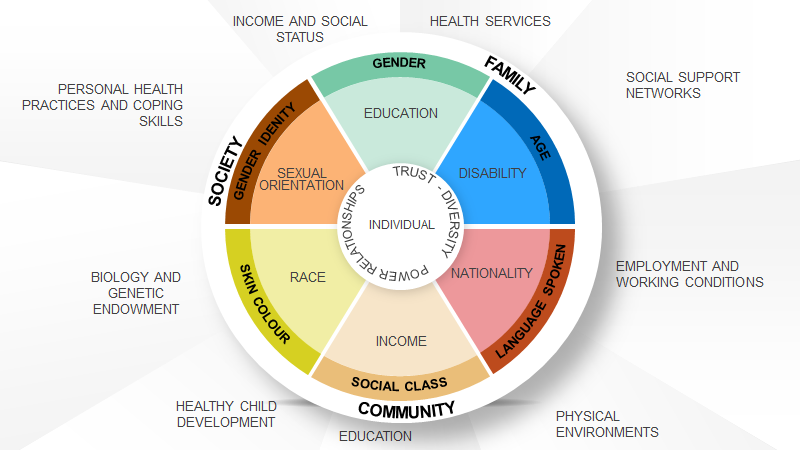

This gender-based prevalent perspective does not account for the rates of violence we see against men and violence we see across gender variant groups (see chapter 5). The gender-based perspective accounts for patriarchal societies that are at the extreme end such as some developing nations but do not necessarily explain the relationship violence along the patriarchy spectrum on non-heterosexual relationships. Therefore, we suggest the model below better reflects current understandings. The NEVR RV Model is an integration of the Socio-environment Model, and, Multiple Ways of Knowing, Intersectionality and Cultural Safety Frameworks. The NEVR RV model accepts that power in relationships is a combination of overlapping processes, socio-environmental interactions that are influenced by multiple roles of people. When working with individuals it is important to recognize one’s position of privilege and create cultural safety for the client. A culturally safe environment is trusting and equal where the client feels that they can be themselves without repercussions and only a client can decide if they are culturally safe. For a fuller discussion, see chapter 6.

Figure 15.3 – NEVR RV Model

Each person working in the RV sector needs to reflect on their own assumptions and power within the system in order to begin to create a culturally safe environment (First Nations Health Authority [FNHA], n.d.). This model accounts for the relationship violence experienced by gender and sexually diverse groups across the lifespan. It questions that males are always the ones with power and can be used to explain the statistics which show similar rates of abuse for males and females (see chapter 5).

Risk Factors for Violence Against Women

Bantams et al. (2018) reported on the risk factors of violence in relationships with female survivors.

Individual Risk Factors

-

-

- Low self-esteem

- Low income

- Low academic achievement/low verbal IQ

- Young age

- Aggressive or delinquent behaviour as a youth

- Heavy alcohol and drug use

- Depression and suicide attempts

- Anger and hostility

- Lack of non-violent social problem-solving skills

- Antisocial personality traits and conduct problems

- Poor behavioural control/impulsiveness

- Borderline personality traits

- Prior history of being physically abusive

- Having few friends and being isolated from other people

- Unemployment

- Emotional dependence and insecurity

- Belief in strict gender roles (e.g., male dominance and aggression in relationships)

- Desire for power and control in relationships

- Hostility towards women

- Attitudes accepting or justifying IPV

- Being a victim of physical or psychological abuse (consistently one of the strongest predictors of perpetration)

- Witnessing IPV between parents as a child

- History of experiencing poor parenting as a child

- History of experiencing physical discipline as a child

- Unplanned pregnancy (CDC, 2019)

-

Risk factors for men who abuse women and girls from WHO (2017) and Neilson (2013).

-

-

- Low education

- History of child abuse

- Witnessed abuse of mother

- Alcoholism

- Unequal gender norms

- Acceptance of violence

- Male privilege

- See women as subordinate

- Situations of conflict, post-conflict and displacement (WHO, 2017)

- Low education

-

According to the First Nations Health Authority (2020), during pandemics such as the COVID-19 when citizens are asked to stay home, RV is a serious threat to many women and girls. Risk factors that are exacerbated are:

-

-

- Stress

- Loss and separation of friends, family, coworkers

- Loss of livelihood/financial hardship

- Loss of homes and resources

- Personal loss

- Uncertainty and anxiety

- Change in housing arrangements

- Breakdown of norms, including loss of routines

- Loss of control

- Stress

-

To learn more about social determinants, visit the National Collaborating Centre on Social Determinants of Health. You will find a library of resources on topics such as intersectoral collaboration, anti-racism and health equity.

COVID-19

A number of resources related to RV and COVID-19 can be found here (Learning Network, 2020).

Pimental reported that women’s shelters are seeing an increase in calls during the COVID-19 pandemic and that women and children have been turned away (National News, 2020). There has been a 300% increase to the 24-hour support line for relationship violence (Eagland, 2020) in the Vancouver, BC area. Toronto City News reported that 10% of women are very concerned about violence in the home during the COVID-19 pandemic (City News, 2020). Eight of twenty-two police agencies in the United States have seen an increase in RV calls (NBC News, 2020). Actions taken depend on available resources, politics and legislation at any given time. There are a number of resources in BC from counselling, shelters, legal services, job programs and parenting programs. A full list can be found on the BC211 website. For the Surrey area, a specific resource of services is the Pink Book (Network to Eliminate Violence in Relationship [NEVR], 2019). You can also access a national report on shelters and transitions houses for abused women and children here (Women’s Shelter Canada, 2015).

The legislation and policies that impact RV are discussed in chapter 9. Resources vary from community to community, with fewer resources being available in the north. There is also the big “P” politics. Politics may interfere with the allocation of resources and actions.

Action

The Network to Eliminate Violence in Relationships (NEVR), along with other stakeholders continues to lobby British Columbia’s government to treat relationship violence like other global epidemics. The Provincial Office of Domestic Violence (PODV) was created in 2011, and NEVR worked closely with the provincial office and was able to provide regular input. PODV worked closely with the Office of the Representative for Children and Youth. With a change in government in 2017, PODV was phased out, and a Parliamentary Secretary of Gender Equality position was created under the Minister of Finance (Government of BC) and coordination responsibility moved to the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General’s Community Safety and Crime Prevention Branch, which has responsibility for victim services and violence against women counselling and outreach programs

PODV operated from a gendered lens and that still is the approach. All ministries are to operate through a gendered lens or GBA+. Relationship violence cuts across multiple ministries, and we all need to work together across all ministries to address this pandemic.

In the past, to highlight the fact that ministries need to work together on RV, a Ministers’ Forum was organized by NEVR and PODV. Seven BC Ministers attended community consultation to hear from community leaders why it is imperative to work together to address RV.

Figure 15.5 – Ministers’ Forum

The Ministers heard from community leaders and vowed to work across ministries. NEVR continues to discuss this issue with local politicians and lobby for a national relationship violence plan and campaign. The Network of NGOs, Trade Unions and Independent Experts created a Blueprint for a National Action plan (Canadian Network of Women’s Shelter & Transition House, 2015). The Canadian federal government (2017) created a Ministry for Status of Women and passed an act to create the Department for Women and Gender Equity Act (2018), and introduced a gender-based analysis plan. This department has worked towards creating a gender-based analysis course and implemented bills to increase representation on boards, management and introduced workplace legislation (Status of Women Canada, 2018). In 2019, The Status of Women Canada passed a framework to create gender equality (Status of Women Canada, 2020). The federal government since 1988 has tried to integrate child abuse and neglect, elder abuse and domestic or intimate partner violence under family violence by collaborating with 12 departments and agencies. You can access the Family Violence Initiative website here and read the materials. In reality, we all need to work off one framework in Canada. Alberta created a framework to end family violence that is a good example of a framework that can be adapted by all jurisdictions (Government of Alberta, n.d.).

The Ministers heard from community leaders and vowed to work across ministries. NEVR continues to discuss this issue with local politicians and lobby for a national relationship violence plan and campaign. The Network of NGOs, Trade Unions and Independent Experts created a Blueprint for a National Action plan (Canadian Network of Women’s Shelter & Transition House, 2015). The Canadian federal government (2017) created a Ministry for Status of Women and passed an act to create the Department for Women and Gender Equity Act (2018), and introduced a gender-based analysis plan. This department has worked towards creating a gender-based analysis course and implemented bills to increase representation on boards, management and introduced workplace legislation (Status of Women Canada, 2018). In 2019, The Status of Women Canada passed a framework to create gender equality (Status of Women Canada, 2020). The federal government since 1988 has tried to integrate child abuse and neglect, elder abuse and domestic or intimate partner violence under family violence by collaborating with 12 departments and agencies. You can access the Family Violence Initiative website here and read the materials. In reality, we all need to work off one framework in Canada. Alberta created a framework to end family violence that is a good example of a framework that can be adapted by all jurisdictions (Government of Alberta, n.d.).

This work in RV still continues in silos. Different ministries and the provinces do not work together, and our literature continues to separate research and toolkits by age and gender. We need academics, service providers, community members (offenders/survivors, family/friends of survivors) and governments to work together and reduce duplication of effort because we need to be efficient and effective and not defend our turfs. We need to use a model that promotes social justice and accounts for relationship violence across genders and sexualities, across age, across dis/abilities etc. As well, we need to value all types of knowledge, both academic and practice. For a full description of types of knowledge and knowing, see Gurm (2013).

Universities can help educate citizens on relationship violence by creating courses based on research and projects completed by the United Nations. The United Nations Global Programme for the Implementation of the Doha Declaration (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, [UNODC], 2019) created education materials on social justice. NEVR member Yvon Dandurand was part of the United Nations Team that created these modules. Several apply to relationship violence. They are created using the best available evidence and expert knowledge. The modules provide lectures, slides, in-class exercises for university faculty to use free of charge to combat injustices. Under the UNODC (2019) Module 10 Violence against women and girls was created. As well, there are training modules for university students. It is good training but it still refers to RV as a gendered crime even though this theory does not explain RV by non-males. The training is available here.

Women can access services to help them address their situation without involving the police, but once the police are involved, then crown counsel may choose to prosecute the partner (see chapter 10). Many services are aimed at making the women independent and providing her with safe space (housing) and then helping her to integrate into society. Women do not take the decision to leave lightly, and there are many reasons why they do not leave (see chapter 8). Also, when they choose to leave, it is the most dangerous time for women because it places them at greater risk of being abused. Some women choose to stay in relationships even though they may be suffering. In this case, they can be made aware of and encouraged to attend counselling, parenting or employment programs to improve their situations. Access BC resources at BC211.

Relationship violence can be classified as a pandemic because it is prevalent in the whole world. Instead of debating if the problem is greater for women or any other group, we need to remain curious and question how society is organized, the norms, resources, policies and institutional practices and how they may be contributing to relationship violence. All stakeholders need to consider using the NEVR RV model above and the NEVR Action model (Chapter 6) and work together to ensure that our interactions, actions and programs and policies are safe and equitable for everyone. We need to address historical oppression and aim to eliminate relationship violence in all its forms.

Initiatives

Shift, The Project to End Domestic Violence is an excellent resource for the prevention of intimate partner violence. We suggest you start with this site. It is a collaboration of government, academics, and multiple agencies focused on stopping violence before it starts. This is an excellent site for anyone looking for information from a multi-agency think tank. It brings together resources on helping address intimate partner violence.

The Canadian initiative to try to understand what are effective programs is the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools for public health. As well, it has a checklist for how to decide if you should continue with your current program, how to set up an evaluation for your program and how to use evidence in practice.

The Centre for Research & Education on Violence against Women & Children is an excellent resource for knowledge and training. One of the things you can learn more about on the website is risk assessment and management. They have regular online training and work on various projects.

The Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative is a knowledge hub. It brings together risk assessment, management, and safety planning strategies. It has a clickable map that highlights work being done in different jurisdictions. Click here for the BC initiatives. Also, for an excellent literature review on preventing domestic homicides, click here.

In a review, the best report was found in the grey literature. A comprehensive report written for Women and Gender Equality Canada is the most comprehensive review of programs that we have found. Crooks et al. (2020) wrote Primary Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls Current Knowledge about Program Effectiveness. This report includes primary prevention programs with evaluation data for schools, bystander intervention programs, programs for specific groups: men and boys, high-risk youth, women with disabilities and indigenous women. It also covers advocacy, change and collaborations. It is a comprehensive report and we suggest, to get a good understanding of how to address intimate partner violence, you read it first.

Several initiatives addressing violence against women were found in the academic literature. Initiatives range from preventive programs offered in schools to advocacy and shelter programs and interventions to improve men’s and women’s relationships. However, many of them have not been evaluated, so there is uncertainty about outcomes. Some studies suggest that evaluating such initiatives is essential, for some programs might be more likely to cause harm than benefits (Ellsberg et al., 2014). In a meta-analysis that evaluated interventions, Rivas et al. (2016) found some evidence that intensive advocacy for women who experience IPV may improve victims’ lives for up to two years after intervention. It is not clear if short-term and brief advocacy interventions may create benefits for those who experience IPV. Among women who most benefit from advocacy, interventions are refugees, pregnant women and those who live in shelters. Although these results indicate mental health benefits, it is not clear if such interventions can reduce abuse.

Tankard, Paluck and Prentice (2019) studied if economic empowerment would lead to social empowerment. They compared the benefits of savings account plus health services vs health services alone in Columbia and found that although depression decreased, IVP victimization did not. In another study, the MAISHA project in which small financial loans are administered to improve women’s economic situation conducted a controlled trial. The intervention group met for 10 sessions to discuss loan repayment and participated in activities to empower women and prevent IPV and the control group only met to discuss loan repayment. There were 485 women in the intervention group and 434 in the control group. At (2 years) follow-up, the risk for sexual and intimate partner violence was 25% less in the intervention group. The risk of intimate partner violence alone was 32% less in the intervention group compared to the control group and this was statistically significant (p=.043). For sexual violence, it was not statistically significant (p=.316). For emotional abuse, the evidence was adequate that the intervention worked (p=.910) (Kapiga et al., p. e1431). Overall, the program was effective in decreasing the risk of intimate partner violence.

Projects, Services and Resources to Prevent IPV

There are also prevention programs listed in the chapter for older adults, children, Indigenous population, LGBTQ2SIA+ and men.

Table 15.1 – List of Programs in Canada

| Agency | Programs | Summary |

| Surrey Women’s Centre | Surrey Women’s Centre | They provide 24 hours services to assist women who may suffer RV. They have emergency, legal, medical and social services for anyone that wishes to access. Originally started for women, they now see men and gender-variant clients. |

| Ending Violence Association of BC | Ending Violence Association of BC | EVABC has a number of initiatives for BC including prevention programs and training for service providers. It is the provincial organization that has as one of its mandates to try to bring information to service providers. |

| Battered Women’s Support Services | Battered Women’s Support Services | BWSS is an initiative created in Canada that offers support to women who have experienced any form of abuse. Besides providing legal resources and advocacy services, the action includes community education and training, support over the phone through a crisis line, online information about economic strategies to deal with challenging financial situations, and a variety of supportive material like strategic safety plan, and transition housing information. |

| The Moose Hide Campaign | The Moose Hide Campaign | The Moose Hide Campaign is an initiative created in BC, Canada, to increase awareness about violence against women. Besides hosting annual meetings and events, they have a presence in many Canadian Universities through specific projects with information about women’s violence and how to prevent it. |

| Out of Violence | Out of Violence | The Out of Violence program is an initiative promoted through the Canadian Women organization—a Canadian foundation—that offers support to women who have experienced different forms of violence like sexual harassment and assault. |

| The Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Program (IPV) | The Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Program (IPV) | The Intimate Partner Violence prevention program is an initiative created through the Canadian Centre for Gender and Sexual Diversity to support LGBTQ2S victims of intimate partner violence. |

| Elizabeth Fry Society of Greater Vancouver | Elizabeth Fry | Elizabeth Fry offers support with shelter, family services, counselling, employment and educational support for women who are at risk of violence. |

Table 15.2 – List of Programs outside Canada

| Agency | Program | Summary |

| MAISHA Project | MAISHA Project | The Maisha is an initiative created in 2014 that aims to understand the impact of providing small financial loans and the impact of gender training in reducing intimate partner violence in Tanzania. Small loans are provided to women through microfinance and gender training (IMAGE) comprises of a set of 10-sessions training every two weeks. |

| preventIPV | preventIPV | It is a website in the US that brings together all national and international resources. It has thousands of resources and links to other resources on such topics as policy, training, programs, etc. |

| National Domestic Violence Hotline | National Domestic Violence Hotline | The NDVH offers a hotline service available in all states of the US, 24-hours a day via phone call, text and online chat, free awareness and educational material on subtypes of violence against women and relationship skills and boundaries, resources like agencies and services available in different states of US. |

| NPY Women’s Council | NPY Women’s Council | The NPY Women’s is an organization established in Australia. Created in 1980, they are focused on providing services to support Anangu women and children in 26 Aboriginal communities in the Central Australia region. |

| The Spotlight Initiative | The Spotlight Initiative | The Spotlight initiative was initiated in 2017 with the collaboration between the European Union and the United Nations. Through working with regional agencies and governmental authorities in 28 countries, this initiative provides strategies and support programs that address patriarchy, social norms, discrimination against women, legislation and policy gaps. |

| Stepping-Stones | Stepping-Stones | Stepping-Stones was created in response to the needs of a religious group that found themselves having critical concerns about intimate partner violence in the community. The program involves community-based participatory learning on intimate partner violence and HIV. This intervention is delivered over 50-hours into groups of women separated from men. |

| The Safe Homes and Respect for Everyone Project (SHARE) | The Safe Homes and Respect for Everyone Project (SHARE) | SHARE is a program created to address intimate partner violence and HIV related infections in Uganda. This intervention includes services like advocacy, community activism, special events, and learning material available to the community. |

References

Anderson, K. L. (2010). Conflict, power, and violence in families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 726-742.

Baird, K. (2015). Women’s lived experiences of domestic violence during pregnancy. Practicing Midwife, 18(9), 37–40.

Bantams, S., Headings, V., & Batsiokis, K. (2018). Strategies to prevent family and sexual violence. Health Outcome International. https://www.hoi.com.au/images/DV-Family-Violence-white-paper-8Oct18.pdf

Barner, J. R., Okech, D., & Camp, M. A. (2014). Socio-economic inequality, human trafficking, and the global slave trade. Societies, 4(2), 148-160.

BC211. (2020). Coronavirus outbreak information. http://www.bc211.ca/home

Boyce, J. (2016). Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2016001/article/14631-eng.pdf?st=wSIzDDxN

Breiding, M. J. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—National intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 63(8), 1.

Burczycka, M., & Conroy, S. (2018). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2016. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54893-eng.pdf

Canadian Network of Women’s Shelters & Transition Houses. (n.d.). A blueprint for Canada’s national action plan on violence against women and girls. https://endvaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Blueprint-for-Canadas-NAP-on-VAW.pdf

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Carter, J. (2015). Patriarchy and violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9978), e40-e41.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Cost of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/IPVBook-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 15). What is intimate partner violence. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VuMCzU54334&feature=youtu.be

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

City News. (2020). Domestic violence calls surge during coronavirus pandemic. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/aps/index.php/aps/article/ view/20894/pdf_31https://toronto.citynews.ca/2020/04/08/domestic-violence-calls-surge-during-coronavirus-pandemic/

Crooks, C., Jaffe, P., Dunlop. C., Kerry, A., Houston, B., Exner-Corten, D., & Wells, L. (2020). Primary prevention of violence against women and girls: current knowledge about program effectiveness. Women and Gender Equality Canada. http://www.learningtoendabuse.ca/our-work/pdfs/Report-Crooks_Jaffe-Primary_Prevention_VAW_Update.pdf

David, J.D. (2017). Homicide in Canada, 2016. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/54879-eng.htm

Department of Justice Canada. (2003). Stalking is a crime called criminal harassment. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/fv-vf/stalk-harc/pdf/har_e-har_a.pdf

Deutsch, H. (1930). The significance of masochism in the mental life of women. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 11, 48-60.

Dillon, G., Hussain, R., Loxton, D., & Rahman, S. (2013). Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2013.

Dobash, R.P., & Dobash, R.E. (2004). Women’s Violence to Men in Intimate Relationships: Working on a Puzzle. The British Journal of Criminology, 44(3), 324–349. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azh026

Dworking, A. (1983). Right-wing women. https://www.feministes-radicales.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Andrea-DWORKIN-Right-Wing-Women-The-Politics-of-Domesticated-Females-19831.pdf

Eagland, N. (2020). Covid-19: Calls to domestic violence crisis line surge, transition homes work to make more space. The Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/news/covid-19-calls-to-domestic-violence-crisis-line-surge-transition-homes-work-to-make-more-space/

Ellsberg, M., Arango, D. J., Morton, M., Gennari, F., Kiplesund, S., Contreras, M., & Watts, C. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say?. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1555-1566.

First Nations Health Authority – FNHA. (n.d.). FNHA position on cultural safety and humility. https://www.fnha.ca/documents/fnha-policy-statement-cultural-safety-and-humility.pdf

First Nations Health Authority – FNHA. (2020). When staying home is not safe: Domestic violence may increase during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.fnha.ca/about/news-and-events/news/when-staying-home-is-not-safe

Flury, M., & Nyberg, E. (2010). Domestic violence against women: definitions, epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Swiss Medical Weekly, 140(3536).

Foucault, M. (1977). Power and sex: an interview with Michel Foucault.

Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., & Watts, C. H. (2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet, 368(9543), 1260-1269.

Gonzáles, L. O. (2017). The role of social and feminist movements in combating domestic violence. II European Conference on Domestic Violence.

Government of Alberta. (n.d.). Family violence hurts everyone: A framework to end family violence in Alberta. http://www.humanservices.alberta.ca/documents/family-violence-hurts-everyone.pdf

Government of Manitoba. (n.d.). The cycle of violence graph. https://www.gov.mb.ca/msw/fvpp/cycle.html

Gracia, E., Lila, M., & Santirso, F. A. (2020). Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women in the European Union: A systematic review. European Psychologist, 25(2), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000392

Gurm, B. (2013). Multiple ways of knowing in teaching and learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7 (1) 4. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ij-sotl/vol7/iss1/4/

Herrero, J., Rodríguez, F. J., & Torres, A. (2017). Acceptability of partner violence in 51 societies: The role of sexism and attitudes toward violence in social relationships. Violence against Women, 23(3), 351-367.

Houston, C. (2014). How feminist theory became (criminal) law: Tracing the path to mandatory criminal intervention in domestic violence cases. Michigan Journal of Gender & Law, 21(2) 217-272. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=mjgl

Hunnicutt, G. (2009). Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women: Resurrecting “patriarchy” as a theoretical tool. Violence against Women, 15(5), 553-573.

Ibrahim, D. (2019). Police-reported violence among same-sex intimate partners in Canada., 2009 to 2017. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00005-eng.htm

Johnson, M. P. (2010). A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Northeastern University Press.

Johnson, M.P. (2011). Gender and types of intimate partner violence: A response to an anti-feminist literature review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. pp. 289-296.

Kapiga, S., Harvey, S., Mshana, G., Hansen, C. H., Mtolela, G. J., Madaha, F., Hashim, R., Kapinga, I.

Mosha, N., Abramsky, T., Lees, S., Watts, C. (2019). A social empowerment intervention to prevent intimate partner violence against women in a microfinance scheme in Tanzania: Findings from the MAISHA cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 7(10), e1423-e1434.

Learning Network. (2020). Resources on gender-based violence and the COVID-19 pandemic. http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/Resources%20on%20Gender-Based%20Violence%20and%20the%20COVID-19%20Pandemic.html

Learning to End Abuse. (2017, October 11). Introduction. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EgMkfr5U-ik&list=PLooxoqkxjFkJdTSLDwldYZWsVf5DbevGi&index=1

Miller, S. (2016). Power and control wheel – Understanding the power and control wheel. Duluth Model. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLOxLVEKmV5blQ31nQ87LOsnjLXlAeYhBZ&v=5OrAdC6ySiY&feature=emb_rel_end

NBC News. (2020). Police see rise in domestic violence calls amid coronavirus lockdown. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/police-see-rise-domestic-violence-calls-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-n1176151

National Center for Victims of Crime – NCVC. (2011). Stalking. https://victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/past-programs/stalking-resource-center/stalking-information

National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence – NCDSV. (n.d.). Power and Control Wheel. http://www.ncdsv.org/images/PowerControlwheelNOSHADING.pdf

National News. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic putting pressure on women’s shelters. https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/covid-19-pandemic-putting-pressure-on-womens-shelters/

Neilson, L. C. (2013). Enhancing Safety: when domestic violence cases are in multiple legal systems. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/famil/enhan-renfo/neilson_web.pdf

Network to Eliminate Violence in Relationship. (2019). Pink book. https://www.kpu.ca/sites/default/files/NEVR/PINK%20BOOK%20FINAL%20PDF%20format%202019.pdf

Office for Victims of Crime – OVC. (2018). Stalking fact sheet. https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_Stalking_508_QC_v2.pdf

Outside of the shadows: a project on criminal harassment in Canada. (2017, December 15). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=85&v=Q9z3BS0qLIQ&feature=emb_logo

Pence, E. (n.d.). Duluth model. https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Duluth-Model.pdf

Pence, E. (2017). Duluth model: Home of the Duluth model. https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Duluth-Model.pdf

Pimental, T. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic putting pressure on women’s shelters. APTN National News. https://aptnnews.ca/2020/03/27/covid-19-pandemic-putting-pressure-on-womens-shelters/

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S. B., McMahon, S., Murshid, N., & Kim, M. (2012). Understanding economic abuse in the lives of survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 411–430.

Rivas, C., Ramsay, J., Sadowski, L., Davidson, L. L., Dunnes, D., Eldridge, S., Hegarty, K., Taft, A., & Feder, G. (2016). Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well‐being of women who experience intimate partner abuse: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 1-202.

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Sanders, C. K. (2015): Economic abuse in the lives of women abused by an intimate partner: A qualitative study. Violence Against Women, 21, No. 1, pp. 3–29.

Shtybel, U., & Artemenko, E. (2016). Economic inequality as an obstacle to development. In Understanding Ethics and Responsibilities in a Globalizing World (201-225). Springer, Cham.

Statistics Canada. (2018). Police-reported intimate partner violence in Canada 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54978/02-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2019). Police-reported violence among same-sex intimate partner in Canada, 2009 to 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00005-eng.htm

Status of Women Canada. (2018). GBA: gender-based analysis plus. https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/course-cours-en.html

Status of Women Canada. (2020). Gender results framework. https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/grf-crrg/index-en.html

Tankard, M. E., Paluck, E. L., & Prentice, D. A. (2019). The effect of a savings intervention on women’s intimate partner violence victimization: Heterogeneous findings from a randomized controlled trial in Colombia. BMC women’s health, 19(1), 17.

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

United Nations. (1993). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/violenceagainstwomen.aspx

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC. (2019). The Doha Declaration. Promoting a culture of lawfulness. https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/crime-prevention-criminal-justice/module-10/index.html

Walker, L.E. (1979). The Battered Women. Harper and Row.

Women’s Shelter Canada. (2015). Blueprint for a National action plan on violence against women and girls. https://endvaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Blueprint-for-Canadas-NAP-on-VAW.pdf

World Health Organization. (2017). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Yllo, K. A., & Straus, M. A. (2017). Patriarchy and violence against wives: The impact of structural and normative factors. In Physical violence in American families. ( 383-400). Routledge.