Chapter 21: Relationship Violence (IPV) in Immigrant and Refugee Communities

Glaucia Salgado and Balbir Gurm

- While the act of migration itself does not cause RV, some factors may increase the risk of abuse. These may include post-migration strain and stigma, the stress associated with migration, geographic and social isolation, changes in socioeconomic status, power imbalances between partners, change in social networks and supports, loss of: culture, family structures, and community leaders; economic insecurity resulting from non-recognition of professional/educational credentials, changes in gender roles and responsibilities and unresolved pre-migration trauma.

- Although protective factors have been identified like the history of religious practices (e.g., Buddhist beliefs), they are often focused on individual factors, so the dynamics within families, physical and social environments are overlooked.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus) (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollè et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death. In this chapter, we bring together understandings of relationship violence on the LGBTQ2SIA+ community.

Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death.

There are multiple factors called social determinants (see chapter 6) that contribute to relationship violence that are mediated by social norms and context. What puts people at risk for RV are:

- Social norms that:

- Normalize heterosexual relationships and myths about male masculinity

- Accept power and privilege

- Accept violence

- Environments that:

- Support inequity

- Are exclusive

- Homelessness

- Conflict

- History of abuse

- Low socioeconomic status

- Violation of the Human Rights Act in Canada (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014)

Immigrants and refugees share the above characteristics (much of what is said in previous chapters (see chapter 1 for chapter summaries) will apply depending on the personal characteristics of those involved in RV, but also note there are differences within each group. Here we discuss the factors that may be unique to immigrants and refugees.

Immigrant refers to someone who migrates to a country other than one’s original country voluntarily, and refugee refers to someone who has been forced to flee one’s own original country due to violence, persecution or war (United Nations [UN], 2020). Immigrants who come to make Canada their permanent home through a legal immigration process are called immigrants, and after 5 years they can apply for citizenship. Some refugees, GARS (Government Assisted Refugees selected by UNHCR) arrive in Canada already with the status of landed-immigrant.

Canada also has a class of migrants called the non-immigrant population, which includes those who temporarily enter the country with a worker or student visa (Statistics Canada, 2016).

Some refugees are able to seek protection in another country. Seeking refuge is a complex process called asylum (i.e., legal process of seeking protection in a foreign country) that is guaranteed to those who are eligible according to the host country’s immigration laws (Government of Canada, 2019). Others live in displacement settings like camps and collective centres (Ezard, 2014).

In 2017, Canada received almost two hundred thousand new migrants, including refugees (Statistics Canada, 2017). Of course, this number includes only official migration and undocumented migrants may exist. The population that seeks migration is very diverse in their individual, economic and social factors. As with any group of people, some have healthy and unhealthy relationships. To read a literature review on immigrant, refugee and non-status women, click here. (Ending Violence Association [EVA], 2009).

Relationship violence among the immigrant population has been described through feminist and patriarchal theories. Besides these theories, experiences of RV among immigrants have been further explained through extenuated experiences linked to post-immigration situations like isolation, cultural changes and barriers, and marginalization (Caplan, 2007; Dow, 2011; Farris, 2002). Following immigration, individuals often experience loss of social networks and social support systems. For those who experience violence in an intimate relationship, losing contact with family members and friends impose a higher level of dependency on the abusive partner (Choncha et al., 2013). A couple who immigrates to another country often has to make new social ties while the previous ones are not available, they have to learn the language, a new way of life, start a new career, and financially support the family. These are considered substantial stressful factors that impact people’s interactions, especially the ones who live in abusive relationships. Cho (2011) suggests that in heterosexual relationships, men who are at high-risk of violence may act more violently towards their partner due to the stress experienced after immigration. Although immigration seems to increase the risk of intimate partner violence among those who already live within abusive relationships, this is not to affirm that migration causes intimate partner violence. Rates of RV in immigrant populations are inconclusive because some studies state higher rates while other studies indicate they are lower compared to the host country (Tabibi et al., 2018). There are no conclusive rates for RV in children or older adult immigrants and refugees as compared to the general population.

Studies analyzing relationship violence and immigration indicate that both financial dependence and independence are connected to women’s vulnerability to experiencing relationship violence from their male partners. Han et al. (2010) suggest that economic dependency serves as a situational facilitator of violence, and men end up acting aggressively towards the female partner. Similarly, women who are financially independent post-immigration are perceived as a threat by their male partners, often increasing the occurrence of intimate partner violence. In this case, the explanation lies in the fact that men might perceive women’s achievement as the loss of men’s power (Morash et al., 2000).

Also, studies show that those with less than a high-school education and lack of literacy in the language of the receiving country face more financial challenges and end up earning very low wages. Immigrants without documented legal status are more likely to live in poverty and other stressful situations like isolation and marginalization that increase the risk of experiencing intimate partner violence (Li & Skop, 2007; Min, 2013).

In addition, cultures strongly linked to patriarchal power, and cultural acceptance of gender inequality play a critical role in the occurrence of intimate partner violence ( Midlarsky et al., 2006; Parish et al., 2004;Yoshioka et al., 2001). Although these are not directly related to immigration patterns, when immigration occurs, women from a visible minority background may face a high risk of intimate relationship violence.

As violence among any group of people is complex, immigrants are subject to relationship violence. This is especially true for couples in which the primary residence holder or the one with the immigration status responsibility is the perpetrator of violence. Although incidence rates are scarce in this field, immigrant couples from a visible minority background who are legally dependent on the violent partner are sometimes more likely to suffer not only domestic violence but also marginalization and social isolation in the receiving country. Since their residence status is dependent on the violent partner, they fear acting on or leaving the abusive relationship and consequently losing the legal status in the receiving country (Lien & Lozerten, 2019). In such cases, IPV may also include threats of deportation if the abusive partner has residency status and the spouse does not. In the UK, in recognition of (mostly) women entering on spousal visas, immigration law was changed to recognize the potential for IPV in relationships. The Domestic Violence clause provides the legal right to remain in cases IPV – click here to access. In Canada immigrants with Permanent Residence are not required to leave if they leave their sponsoring spouse and options exist for those with temporary status also, click here to read more.

Some commonalities of immigrant and refugee populations that may increase the risk for abuse are:

- Post-migration strain and stigma

- Stress associated with migration

- Geographic and social isolation

- Changes in husband and wife’s socioeconomic statuses

- Power imbalances between partners

- Change in social networks and supports

- Loss of culture, family structures, and community leaders

- Economic insecurity resulting from non-recognition of professional/educational credentials

- Change in gender roles and responsibilities

- Unresolved pre-migration trauma (Tabibi et al., 2018)

Most of the information on refugees and immigrants is about women. Some additional risks specific for refugee and immigrant include (Neighbours Friends, & Families, n.d.):

- The violence may include threatening to withdraw sponsorship

- May be at risk of RV from those who sponsored them

- May be at risk from anyone who is helping them or an employer (power position)

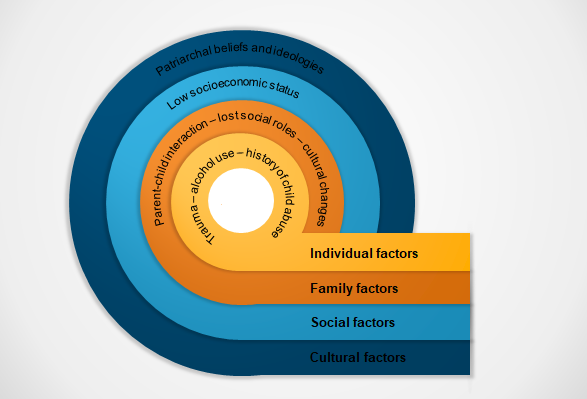

Refugees who live in camps and communal centres face many stressful situations. From traumas suffered in the original country to challenges related to the displacement and collective living. Studies suggest that the displaced population is at higher risk of alcohol use that has been associated with higher chances of experiencing relationship violence, especially among intimate partners (Weaver & Roberts, 2010). Ezard (2014) shows that alcohol use tends to be extremely high among refugee men living in displacement centres. He explains that alcohol consumption was promoted and encouraged in refugee camps leading to alcohol-related violent behaviours towards female partners. Other than the alcohol effect in the experiences of RV, systematic reviews indicate that previous and current traumatic experiences, parental childhood experiences of child abuse, poor parent-child interaction, breakdown of social roles among men and women, low socioeconomic status, stress due to cultural changes, and patriarchal cultural norms and ideologies were strong factors associated with the incidence of relationship violence among refugees. These factors create an increased risk of experiencing relationship violence among family members, especially for women and children (Timshel et al., 2017). Many of these risks are identified for all groups (see chapter 6). Individual risk factors specific to immigrants are in figure 21.1: culture that accepts gender inequality, legal immigration status linked to one of the partners, low level of education and low financial status. Although these are risk factors, it does not mean that every single person who has these characteristics is going to be abused. These are generalizations based on data, but may not apply to any single person.

Figure 21.1 – Risk Factors – Individual Level

Although protective factors are identified like the history of religious practices (e.g., Buddhist beliefs), they are often focused on individual factors, so the dynamics within families, physical and social environment are overlooked (Timshel et al., 2017). From the NEVR model, protective factors are practices of human rights in law and policy. These need to be integrated into all social structures and processes.

Figure 21.2 – Risk factors of Relationship Violence among Refugees

It should not be assumed that all relationships are heterosexual for there are gender variant identities in all races, cultures, and societies. Immigrants and refugees also have multiple roles and realities (see chapter 6) and it is prudent to highlight the intersectionality of race and gender (see TED x on the Urgency of Intersectionality). All the social determinants of health are applicable overall but not all may be applicable to any one person. It is the role of those working with immigrants and refugees to use this information as background and practice cultural safety when working with clients to understand their specific risks, needs and desires.

Initiatives

There are many organizations in Canada that provide support to immigrant and refugee families. Most of the time services include not only violence prevention programs but also initiatives that support factors involved in relationship violence like unemployment and lack of social connectedness. There are many resources and successful programs including labs that are partnerships between universities, community agencies and businesses such as Simon Fraser University’s Refugee Livelihood Lab.

Some resources are specific to immigrants and refugees in Canada, mostly BC & Lower Mainland are:

Table 21.1 – List of programs available to Immigrants and Refugees in Canada

| DIVERSEcity Community Resources Society | DIVERSEcity Community Resources Society | This is a non-profit organization based in Surrey, British Columbia that offers services to newcomers in Canada. Services are offered for free in many languages like Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, Korean, Mandarin, Punjabi, Spanish, Farsi and English. They also have a specific program to support LGBTQ2SIA+ newcomers. |

| Options Community Services | Options | This is a non-profit organization based in Surrey, British Columbia. The have a variety of programs and services including 5 programs specifically for immigrants/refuges for settlement and RV in multiple languages including the Caring Dad’s program in Punjabi. |

| MOSAIC | MOSAIC | This is one of the largest non-profit organizations serving newcomers with services in the lower mainland. This organization offers a range of services to immigrants and refugees in multiple languages. |

| Vancouver & Lower Mainland Multicultural Family Support Services Society – VLMFSS | Vancouver & Lower Mainland Multicultural Family Support Services Society | VLMFSS is located in Burnaby and it is focused on offering services to immigrants, refugee women without immigration status and their family, and visible minority families. All services are free and confidential. Programs/services are offered in 20+ languages and include programs specific to RV as well as legal services |

| Ending Violence Association of BC – EVABC | The Safety of Immigrant Refugee and Non-Status Women Project | This is a project that EVABC developed in partnership with MOSAIC to consult, analyze and address issues related to the safety of immigrants, refugees and women who are in Canada without holding a legal status. |

| Progressive Intercultural Community Services – PICS | PICS | This is a non-profit society with their main office in Surrey, BC. They offer a number of employment and English training programs and are involved in the Senior’s isolation project. |

| Neighbours, Friends and Families Immigrant & Refugee Communities | Violence Against Refugee Women | This website shows information about domestic violence among refugee women, characteristics of this violence and resources to support prevention. To contact the helpline, please call, 1 866 863 0511 / TTY 1 866 863 7868. |

| Immigrant Services Society of BC | ISSofBC | This organization provides a variety of services to immigrants and refugees. Besides settlement aid, they also offer |

| S.U.C.C.E.S.S BC | S.U.C.C.E.S.S. BC | The largest non-profit that offers newcomer settlement, English-language training, employment and entrepreneurship, family, youth and seniors programming, health education, community development, affordable housing, and seniors care. It has multilingual staff and over 40 service centres across Canada and Asia |

Table 21.2 – List of Programs outside Canada

| Agency | Program | Summary |

| Refugee Women’s Alliance | Refugee Women’s Alliance | Refugee Women’s Alliance (ReWA) is an award-winning, nationally recognized nonprofit that provides holistic services to help refugee and immigrant women and families thrive. In 35 years of work with multi-cultural communities, we have refined our services to most effectively promote integration and self-sufficiency. All of our services are designed to quickly and effectively stabilize clients, promote acculturation, increase language proficiency, and improve employability. |

| US Department of Health and Human Services | Office on Women’s Health | This initiative provides information about violence against immigrant and refugee women. It also gives information about restraining orders and how to access resources in the community. |

| Child Welfare Information Gateway | Helping Immigrant Families | Resource with service provides information and how to access them |

| Multi-cultural Centre for Women’s Health | On Her Way | Literature that contains information about fact and preventive programs against violence towards. immigrant and refugee women in Australia. |

| ANROWS | ANROWS | Information about experiences of violence against immigrant and refugee women and preventive program resources. in Australia. |

| Futures without Violence Organization | Future without Violence | This initiative has many programs that provide information and support to different population groups including immigrant and refugee women and men. |

See general resources for RV in other chapters or go to the BC211 website.

References

Caplan, S. (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 8, 97–106.

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Risk and protective factors for perpetration. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

Cho, H. (2011). Racial differences in the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women and associated factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(2), 344–363.

Concha, M., Sanchez, M., de la Rosa, M., & Villar, M. E. (2013). A longitudinal study of social capital and acculturation-related stress among recent Latino immigrants in South Florida. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 35(4), 469–485.

Crenshaw, K. (2016, December 7). The urgency of intersectionality. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akOe5-UsQ2o

Dow, H. D. (2011). The acculturation process: the strategies and factors affecting the degree of acculturation. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 23(3), 221–227.

Ending Violence Association. (2009). Safety for immigrant, refugee and non-status women: A literature review. https://endingviolence.org/files/uploads/IWP_Lit_Review_for_website_May_2010.pdf

Ezard, N. (2014). It’s not just the alcohol: gender, alcohol use, and intimate partner violence in Mae La refugee camp, Thailand, 2009. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(6), 684-693.

Farris, C. A., & Fenaughty, A. M. (2002). Social isolation and domestic violence among female drug users. American Journal of Alcohol Abuse, 28(2), 339–351.

Government of Canada. (2019). How Canada’s refugee system works. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role.html

Han, A. D., Kim, E. J., & Tyson, S. Y. (2010). Partner violence against Korean immigrant women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(4), 370–376.

Li, W., & Skop, E. (2007). Enclaves, Ethnoburbs, and new patterns of settlement among Asian immigrants. In M. Zhou & J. Gatewood (Eds.), Contemporary Asian America: A multi-disciplinary reader (2nd ed., pp. 222–236). New York University Press.

Lien, M., I. & Lorentzenm J. (2019). Men’s experiences of violence in intimate relationships. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-030-03994-3.

Midlarsky, E., Venkataramani-Kothari, A., & Plante, M. (2006). Domestic violence in the Chinese and South Asian immigrant communities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1087, 279– 300.

Min, P. G. (2013). The socioeconomic attainments of Korean Americans, compared to native-born Whites and other Asian groups, in the NYNJ-CT CMSA: Generational differences. Research Report 5. The Research Center for Korean Community: Queens College of CUNY.

Morash, M., Bui, M., & Santiago, A. (2000). Gender-specific ideology of domestic violence in Mexican origin families. International Review of Victimology, 1, 67–91.

Neighbours, Friends & Families. (2018). http://www.neighboursfriendsandfamilies.ca/content/research-briefs

Parish, W. L., Wang, T., Lumann, E. O., Pan, S., & Luo, Y. (2004). Intimate partner violence in China: national prevalence, risk factors and associated health problems. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30(4), 174–181.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2014). What puts families at risk and what helps protect them? https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/families-risk-violence-what-helps-protect-them.html

Radius Refugee livelihood Lab. (n.d.). What is the refugee livelihood lab?. https://radiussfu.com/programs/labs-ventures/refugee-newcomer-livelihood/

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex Couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Statistics Canada. (2016). Immigrant. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=Unit&Id=85107

Statistics Canada. (2017). Income of immigrants taxfilers. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=4310001601

Tabibi, J., Ahmad, S., Baker, L., & Lalonde, D. (2018). Intimate partner violence against immigrant and refugee women. Learning Network, 26.

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

Timshel, I., Montgomery, E., & Dalgaard, N. T. (2017). A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated with family-related violence in refugee families. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 315-330.

United Nations. (2020). Refugees and migrants. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions

Weaver, H., & Roberts, B. (2010). Drinking and displacement: A systematic review of the influence of forced displacement on harmful alcohol use. Substance Use and Misuse, 45(13), 2340–2355.

Yoshioka, M. R., DiNoia, J., & Ullah, K. (2001). Attitudes toward marital violence: An examination of four Asian communities. Violence Against Women, 7(8), 900–926.