Chapter 19: Relationship Violence in Indigenous Populations

Balbir Gurm

- A disproportionate number of Indigenous families are investigated and their children placed in child welfare services and a disproportionate number of Indigenous adults are incarcerated. Sexual assaults and intimate partner violence against Indigenous women are significantly more likely compared to non-Indigenous women.

- Traditionally among Indigenous communities, women were valued and held leadership roles. Many of these cultural practices were disrupted by colonization. Many children endured physical, sexual and emotional abuse and neglect in the residential schools. The disconnection from their families, communities and culture had a long-term negative effect on many.

- The traumatic experience of residential schools, the Indian Act and other efforts to eradicate Indigenous cultural and familial practices and traditions, along with continued inequities, systemic racism and lack of cultural safety within systems, has left many Indigenous populations at greater risk of perpetuating the relationship violence cycle.

- To understand the complexity of abuse in vulnerable groups such as in the Indigenous population, it is important to overlay the intersectionality framework.

- In order for programs for Indigenous peoples to be culturally appropriate and safe, they must draw upon Indigenous knowledge and experiences, be informed by Indigenous practitioners and elders, must restore connections to Indigenous identity, spirit and spirituality, value respect, wisdom, responsibility and relationships. Traditional beliefs such as connection to culture and incorporating the wisdom of elders and story-telling decrease trauma and grief and facilitate healing.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SAI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus) (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollè et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death. This chapter is committed to the people to who’s land we have immigrated to, Indigenous communities. Many of them suffer generational trauma and are at higher risk than the mainstream Canadian.

Relationship Violence in Indigenous Populations

…harm did not end when they walked out the school doors for the last time. Rather, Indigenous societies and families continued to face trauma for generations after, trauma from which we are all still struggling to heal. Unfortunately, one of the lasting legacies is an alarmingly high rate of violence against Indigenous women and girls (Chief Wilton Littlechild in Mckay & Cree, n.d., p. 11).

Traditionally among Indigenous communities, women were valued and held leadership roles. With the arrival of colonizers, over time, Indigenous communities got disconnected from their culture. This group has commonalities with other groups, but there are specific differences.

Indigenous women are three times more likely to be subject to sexual assaults than non-Indigenous women, and intimate partner violence is twice as likely compared to non-Indigenous women (Perreault, 2011). Indigenous people are grossly over-represented in the incarcerated population – in 2017 and 2018, Indigenous people made up 3% of the population yet constituted 27% of those in prison (Malakieh, 2019). It is important to note that 50% of those incarcerated were impacted by relationship violence as children (Bodkin et al., 2019).

It is important to keep in mind other experiences endured by Indigenous communities in Canada that impact relationships and can create both individual and community trauma. For example, the statistics for MMIWG (murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls) are shocking, with Indigenous women and girls twelve times more likely to be murdered and/or missing than any other group in Canada (The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019). In addition, Indigenous children are apprehended by government authorities and placed in child welfare services at disproportionate rates (Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative, 2018, p. 7), sometimes for reasons related to intergenerational trauma.

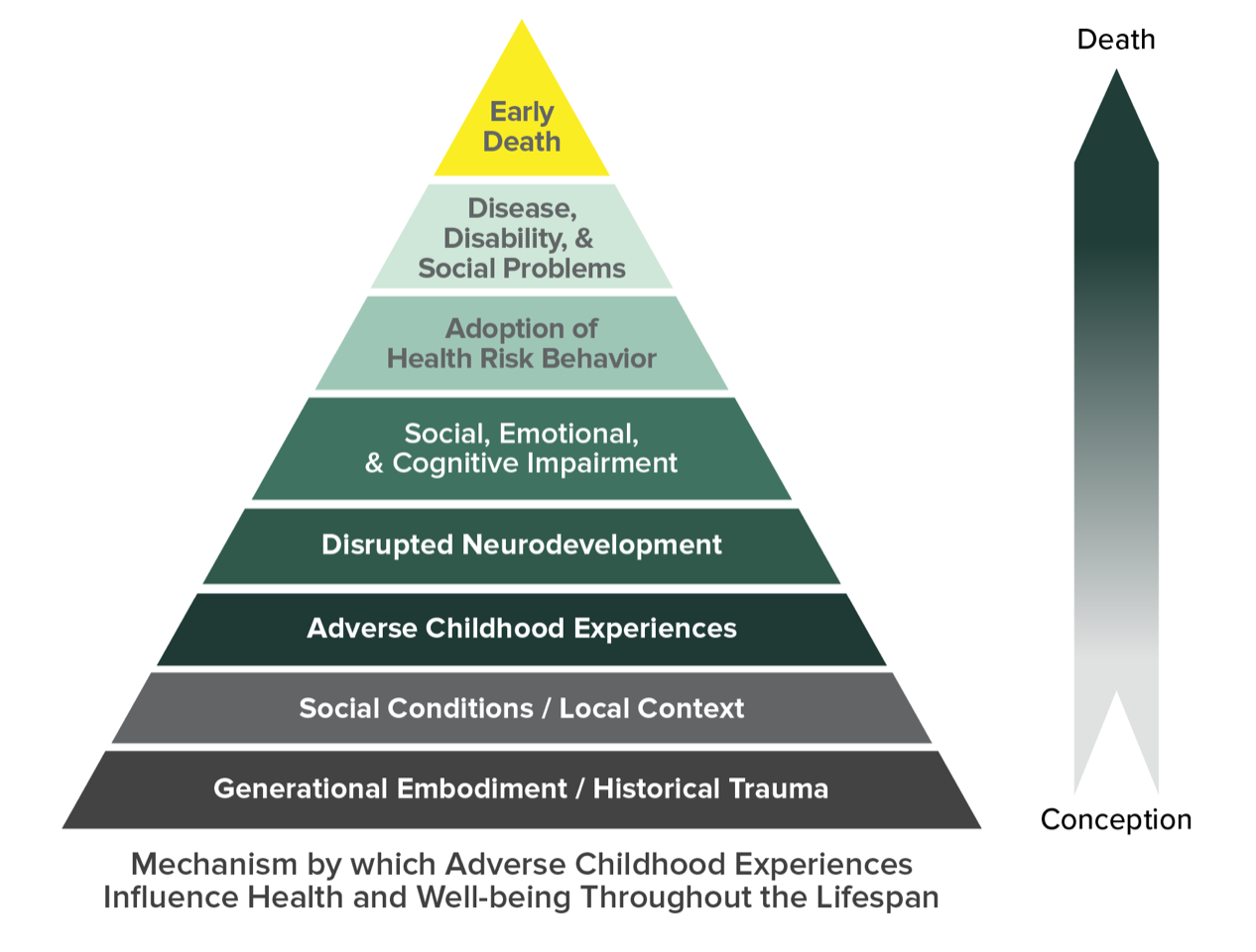

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC, 2015) captured the traumatic experiences Indigenous communities had to endure in the hands of the colonizers. This report also outlined how colonizers systematically and forcefully took Indigenous children away from their parents and communities and placed them in residential schools. Here, they were forced to learn the language and culture of the colonizers. Many children endured physical, sexual and emotional abuse and neglect in the residential schools. The disconnection from their families, communities and culture had a long-term negative effect on many. While there has been some progress in ensuring more culturally sensitive supports and services, according to a 2016 Canadian Human Rights Tribunal decision, there remains systemic discrimination against Indigenous people, for instance, the Canadian government has underfunded children and families on reserves compared to ministries of children and families in other jurisdictions. The long-lasting underfunding may have been a contributor to ongoing neglect and abuse among Indigenous communities which can also lead to intergenerational trauma. See video on intergenerational trauma (Historica Canada, 2020). Figure 19.1 shows the trajectory of health and social challenges when generational trauma such as residential schools is passed on at conception. It leads to multiple conditions such as adverse childhood experiences, disrupted neurodevelopment, social, emotional and cognitive impairment, risky health behavior and chronic health conditions including RV and early death.

Figure 19.1 Childhood Experiences Impact on Health & Well-being (CDC, 2020)

The traumatic experience of residential schools left many Indigenous populations with greater risk perpetuating the relationship violence cycle. Many Indigenous people experienced sexual, emotional, physical, mental, spiritual and cultural abuse in residential schools and the TRC called the experience of Indigenous peoples in Canada cultural genocide (TRC, 2017, p. 10). The last federally funded residential school closed in 1996 so this is not an issue just of the past but also of our present as survivors are with us as are their descendants. To read a synopsis of the history of residential schools, click here (Legacy of Hope Foundation, n.d.).

Intergenerational trauma can result in:

- Negative parenting behaviours and these can be passed on from generation to generation if the families are in a community where it is the norm

- Lack of parent-child bonding can impact brain development leading to decrease cognitive skills, lack of trust and social inadequacy resulting in psychological trauma that is also intergenerational

- Toxic stress which can also be passed on through generations (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2020)

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls tried to understand the staggering statistics and systemic causes of relationship violence against Indigenous women and girls. Apart from rates of RV being higher, many Indigenous communities face many inequities – inadequate supports and services, poverty, overcrowding, lack of housing, drug and alcohol abuse, mental health issues, low income and education that puts them at higher risk (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Report, 2019).

Indigenous populations around the world report similar experiences and much has been documented about the experience of Aboriginal peoples of Australia and New Zealand (Bamblett et al., 2018). Similar to the TRC, the Australian Royal Commission inquiry into institutional responses to child sexual abuse found that most children had been sexually abused in faith-based institutions, mainly Catholic institutions. The majority of those reporting sexual abuse were boys (64.3%) with 50% of them reporting that the abuse occurred when they were 10-14 years old. Girls reported being abused at younger ages. In cases of abuse of both girls and boys, 93.8% of perpetrators were male.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) states that those who have suffered RV themselves are at greater risk. The risk factors for child abuse are the experiences endured at residential schools and systemic racism. They are not specific to Indigenous people but Indigenous people have increased likelihood of facing these risks due to poverty, racism, living on reserves, being distant from services and supports, they include:

Individual Risk Factors

-

- Parents’ lack of understanding of children’s needs, child development and parenting skills

- Parental history of child abuse and or neglect

- Substance abuse and/or mental health issues including depression in the family

- Parental characteristics such as young age, low education, single parenthood, a large number of dependent children, and low income

- Nonbiological, transient caregivers in the home (e.g., mother’s male partner)

- Parental thoughts and emotions that tend to support or justify maltreatment behaviour

Family Risk Factors

-

- Social isolation

- Family stress, separation or divorce, and violence, including intimate partner violence

- Parenting stress, poor parent-child relationships, and negative interactions

Community Risk Factors

-

- Community violence

- Concentrated neighbourhood disadvantage (e.g., high poverty, high unemployment rates, and high density of alcohol outlets), and poor social connections (CDC, 2020)

According to the First Nations Health Authority (2020), during pandemics such as the COVID-19 when citizens are asked to stay home, RV is a serious threat to many women and girls. Risk factors that are exacerbated are:

-

- Stress

- Loss and separation of friends, family, co-workers

- Loss of livelihood / financial hardship

- Loss of homes and resources

- Personal loss

- Uncertainty and anxiety

- Change in housing arrangements

- Breakdown of norms, including loss of routines

- Loss of control (First Nations Health Authority, 2020)

Intersectionality

To understand the complexity of abuse in vulnerable groups, such as in the Indigenous population, it is important to overlay the Intersectionality framework. Intersectionality theory explains how identity, experience and positionality intersect to create a matrix of oppression that underpins relationship violence (Cramer & Plummer, 2009; Meyer, 2010). See Intersecting Axes of Privilege, Domination & Oppression and place the person on the wheel to understand the totality of the person. Increased risk results from historical, political, and socioeconomic realities, and the normalization and generational transmission of violence that may lead to a culture that normalizes abuse. The history and impact of residential schools and the inadequate living conditions and the code of silence to protect the family and community unity may all contribute to not reporting RV (Cooper, 2017).

Part of the intersectional framework is to become/remain aware of the effects of historical and current discrimination. For example, The Indian Act enshrined into law racially discriminatory policies, such as having to renounce Indian status to vote (Justice Laws, 2019). The Indian Act also stripped women of their Indian status if the ‘married out’. The effects of this Act are still subject to challenges to the government today.

In addition to the above, economic dependency, poverty, lack of parenting skills, formal education, geographic isolation, government and historical structures in remote communities increase the risk of Indigenous peoples (Brassard et al., 2015). Across Canada, there is a history of colonialism, racism and white privilege. For many years, practitioners were told to become culturally competent and many books and articles were written on how to deal with Indigenous and other specific populations. However, generalizations were published about groups. When generalizations are applied to every single person of a given group, it leads to stereotyping. That is why oppressed people feel that the system and its services that are not informed by Indigenous knowledge revictimize them. This results in many Indigenous populations not having a sense of cultural safety.

Cultural Safety

Systemic racism and power imbalances endured by any group can be addressed through cultural safety. In nursing education, cultural safety was first introduced by Irahapeti Ramsden (2002) a Maori nurse. In her doctoral dissertation, she addressed the historical oppressions that have led to higher rates of illness in the Maori population than in the general population of New Zealand/Aotearoa. Cultural safety examines prejudice, power and bicultural relations. It can be applied to any person or group that differs on any axis of privilege, domination and oppression (age, ability, ethnicity, sexual orientation, migrant status, religious belief, socioeconomic status, education, etc.). Please, see chapter 6 for a fuller discussion. It is about the unique bicultural relationship of two people and the focus is on the service provider/employer/educator/boss to create a trusting environment and equal partnership with the person who is in an oppressed position. Only the recipient can decide if cultural safety has been achieved. The focus is on the one with the power to reflect on their power and assumptions in order not to stereotype but listen to and understand the other person. Cultural safety is practiced through cultural humility and the following occurs:

- Service providers become curious and reflective practitioners

- Practitioners reflect on their own biases and confront their prejudices

- Respectful communication that recognizes historical and systematic (organizational/societal) oppression

- Creating an equal partnership between those who are communicating with each other

- Creating a trusting environment

This can result in an environment that respects diversity and is free of racism and discrimination (Ramsden, 2002).

Barriers

As with all groups many Indigenous survivors do not report incidences of IPV nor access services. The Public Health Agency of Canada (2012) lists several reasons for Indigenous people not accessing services:

- Low awareness of them

- Their distance from the home community

- The lack of transportation

- Poor relationships with the police

- Lack of faith in the effectiveness of the resources

- Lack of privacy in communities and the consequent shame about accessing resources

- Complex relationships among the victim, the abuser, their families and other community members

- The desire to keep the family intact at all costs because of fear of the unknown and of losing face, as well as the possibility of losing one’s children, home and assets (Holmes & Hunt, 2017).

Programs and Services

In order for programs for Indigenous peoples to be culturally appropriate and safe, they must draw upon Indigenous knowledge and experiences, and be informed by Indigenous practitioners and elders. In addition, they must restore connections to Indigenous identity, spirit and spirituality (Black et al., 2019; Puchala et al., 2010) and value respect, wisdom, responsibility and relationships (First Nation Health Authorities, n.d.). In addition, traditional beliefs such as connection to culture improve healing (Gilmour, 2013; Reeves & Stewart, 2015) and incorporating the wisdom of elders and story-telling decreases trauma and grief (Marsh et al., 2016; Puchala et al., 2010).

Policies written are not always policies practiced and sometimes change takes generations. There are several frameworks and action plans in existence, see agencies listed below.

Table 19.1 List of Programs

| Agency in Canada | Initiative | Summary |

| Government of Canada | Stop Family Violence | A one-stop resource for family violence that includes information on abuse across the lifespan, where to access help and locate shelters. |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Violence Prevention | Best practices available at the Public Health Agency of Canada. |

| Government of Canada | National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health | A national centre to bring together knowledge and Indigenous communities to synthesize the best evidence. It is meant to be a one-stop-shop for Indigenous health. It has publications on family violence. |

| Canadian Women’s Foundation | Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative

|

It provides the history and current context of the Aboriginal community. It also provides effective assessment tools and programs. |

| Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada | It is a result of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. The commission interviewed survivors of residential schools over a six-year period. A summary of the report describes the horrible atrocities endured by residential school survivors, as well as history, context and recommendations for healing. |

| National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls | National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls | Interviews of over 6,000 people to understand the systemic causes of (relationship violence) sexual assault, child abuse, domestic violence, bullying and harassment, suicide, and self-harm and made recommendations. |

| National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence. | National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence | It has a number of resources for shelter workers. An important resource is the best practices for shelters. |

| National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence | Ending Violence In Aboriginal Communities: Best Practices In Aboriginal Shelters and Communities |

A summary report based on consultations with twelve on-reserve women’s shelters from across the country. In addition to best practices, the report also considers barriers and challenges, shelter profiles, observations and conclusions. |

| First Nations Health Authority | Traditional Healing | It provides a health and wellness framework that can be used by service providers. |

| Strength, Masculinities and Sexual Health | SMASH Initiative | Work with young boys and men to help formulate healthy gender identities and develop respect for all beings. They also have links to multiple resources. |

| Fostering Open Expression among Youth | FOXY Program | Provide support to girls and gender diverse individuals that teach them about healthy relationships and sexual health. It is an award-winning program. |

| Ending Violence Association of BC | Indigenous Community Safety Project | Assist Indigenous communities and leadership understand the justice and family systems and child protection laws and policies that directly impact policy and government agency responses to relationship violence. |

| Agency outside Canada | Initiative | Summary |

| Healing Foundation – Australia | Healing Foundation – Community Healing | It has several programs that are deemed effective to address and prevent relationship violence as well as resources on intergenerational trauma. |

References

Bamblett, M., Blackstock, C., Black, C., & Salamone, C. (Eds.). (2018). Culturally respectful leadership: Indigenous staff and clients. In Frederico, M., Long, M., & Cameron, N. Leadership in child and family practice, Routledge Academic, 103-119.

Black, C., Frederico, M., & Bamblett, M. (2019). Healing through connection: An Aboriginal community designed, developed and delivered cultural healing program for Aboriginal survivors of institutional child sexual abuse. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 1059-1080.

Bodkin, C., Pivnick, L., Bondy, S. J., Ziegler, C., Martin, R. E., Jernigan, C., & Kouyoumdjian, F. (2019). History of childhood abuse in populations incarcerated in Canada: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of public health, 109(3), e1-e11.

Brassard, R., Montminy, L., Bergeron, A. S., & Sosa-Sanchez, I. A. (2015). Application of intersectional analysis to data on domestic violence against aboriginal women living in remote communities in the province of Quebec. Aboriginal Policy Studies, 4(1), 3-23. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/aps/index.php/aps/article/view/20894/pdf_31

Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. (2018). Domestic violence risk assessment, risk management and safety planning with Indigenous populations. http://cdhpi.ca/sites/cdhpi.ca/files/Brief_5-Online_0.pdf

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Centers for Disease and Prevention. (2020). Violence prevention: risk and protective factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html

Cooper, Y. (2017). Intersectionality. https://www.ncda.org/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/139052/_PARENT/CC_layout_details/false

Cramer, E. P., & Plummer, S. B. (2009). People of color with disabilities: Intersectionality as a framework for analyzing intimate partner violence in social, historical, and political contexts. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(2), 162-181.

First Nations Health Authority – FNHA. (2020). Novel coronavirus. https://www.fnha.ca/

First Nations Health Authority – FNHA. (n.d.) First Nations Perspective on Health and Wellness. https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-and-the-first-nations-health-authority/first-nations-perspective-on-wellness

Gilmour, M. (2013). Our Healing Our Solutions – Sharing our evidence. Healing Foundation. https://healingfoundation.org.au/app/uploads/2017/01/HF-OHOS-ALT-July2015-SCREEN-singles.pdf

Historica Canada. (2020, March 9). Intergenerational trauma: residential schools [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWeH_SDhEYU&feature=youtu.be

Holmes, C., & Hunt, S. (2017). Indigenous communities and family violence: Changing the conversation. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-FamilyViolence-Holmes-Hunt-EN.pdf

Justice Laws. (2019). Indian Act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/

Legacy of Hope Foundation. (n.d.). 100 years of Loss. http://legacyofhope.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/100-years-print_web.pdf

Malakieh, J. (2019). Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2017/2018. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00010-eng.pdf?st=9brPh50M

Marsh, T. N., Cote-Meek, S., Young, N. L., Najavits, L. M., & Toulouse, P. (2016). Indigenous healing and seeking safety: A blended implementation project for intergenerational trauma and substance use disorders. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(2), article 3. https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/view/7488/6132

McKay, C., & Cree. (n.d.). ANANGOSH: legal information manual for shelter workers. http://nacafv.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Legal-Information-Manual.pdf

Meyer, D. (2010). Evaluating the severity of hate-motivated violence: Intersectional differences among LGBT hate crime victims. Sociology, 44(5), 980-995.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: the final report on the National inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

Perreault, S. (2011). Violent victimization of Aboriginal people in the Canadian provinces, 2009. Statistics Canada Catalogue .https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2011001/article/11415-eng.pdf?st=_mtrXpic

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012). Aboriginal Women and Family Violence – Detailed findings. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/prevention-resource-centre/aboriginal-women/aboriginal-women-family-violence.html

Puchala, C., Paul, S., Kennedy, C., & Mehl-Madrona, L. (2010). Using traditional spirituality to reduce domestic violence within Aboriginal communities. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(1), 89-96.

Ramsden, I.M. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu: A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing.

Reeves, A., & Stewart, S. L. (2015). Exploring the integration of Indigenous healing and western psychotherapy for sexual trauma survivors who use mental health services at Anishnawbe Health Toronto. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 49(1), 57-78. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/61008/46301

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (2017). Final Report Preface and Executive Summary. https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_preface_and_executive_summary.pdf

The Canadian Encyclopedia. (2020). Intergenerational trauma and residential schools. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/intergenerational-trauma-and-residential-schools

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). Creating change together: Trans Equality in Scotland. https://www.scottishtrans.org/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf