Chapter 18: Relationship Violence Against Men

Balbir Gurm; Glaucia Salgado; and Jennifer Marchbank

Key Messages

- Meta-analysis of studies on relationship violence in which men are victims indicate psychological and physical violence seems to be the most prevalent form of RV experienced.

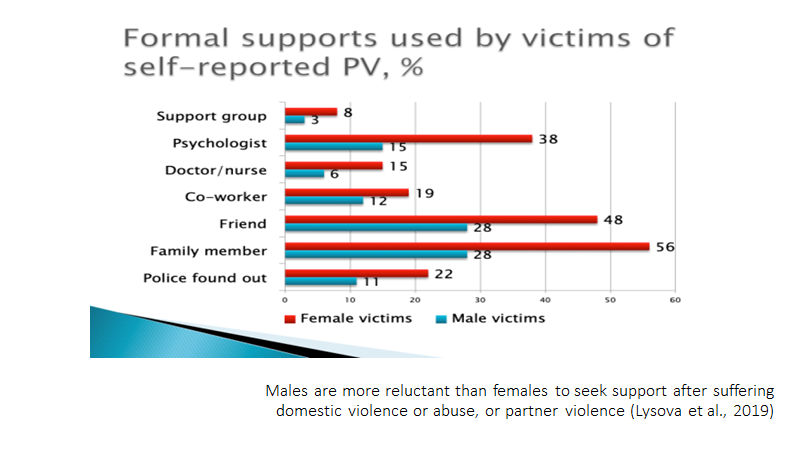

- Barriers to seeking help include fear of disclosure (shame, denial and embarrassment, fear of not being believed, nowhere to go and fear of losing children), challenge to masculinity, commitment to relationship, diminished confidence/despondency that inhibits action and invisibility/perception of services (victim not aware of services or thought they were inappropriate).

- Victims who seek out help may experience distress and secondary victimization when professionals and services are not prepared to provide support to this population group.

- Access to support services among male victims of intimate partner violence is typically considerably lower than services for women.

- Misconceptions about what it means to be a man often stand in the way of sexual abuse and other forms of abuse of males being recognized, acknowledged, and treated. Alcohol and drug abuse, family violence, suicide and social dysfunction are a few of the possible consequences.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus) (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollè et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death. Although men are usually the perpetrators of RV, they can also be abused. This chapter illuminates the understandings of RV against men.

Relationship Violence against Men

Relationship violence issues have typically been focused on violence committed against women and girls, particularly concerning intimate partner violence and sexual violence. As widely discussed previously, women and girls are vulnerable to violent acts with reasoning around issues related to patriarchy and imbalanced power relationships (Carter, 2015). Although this view has been conceptualized as a unilateral approach suggesting that men are the sole perpetrators of violence, and women the victims, studies assert that individuals from any gender can be victims of violence (Devries, 2013; Ferrales et al., 2016; Meyer, 2015). It is noteworthy that gender refers to socially and culturally constructed norms associated with being male or female. Sex assigned at birth does not always correspond with an individual’s gender. Violence might occur with individuals who identify themselves as male, female, and LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex, asexual) (Bradley, 2013; Todahl et al., 2009; United Nations [UN], 1996). Although power and patriarchy are most frequently used to discuss violence against females, they are also recognized as critical factors affecting any group of vulnerable individuals. The reason for the extensive use of these concepts is connected to the fact that privilege, power, and dominance intersect with social status, race, ethnicity, and religion (Sidanius & Veniegas, 2013). Intersectionality theory explains how identity, experience and positionality overlap to create oppression that underpins relationship violence (Cramer and Plummer, 2009; Meyer, 2010).

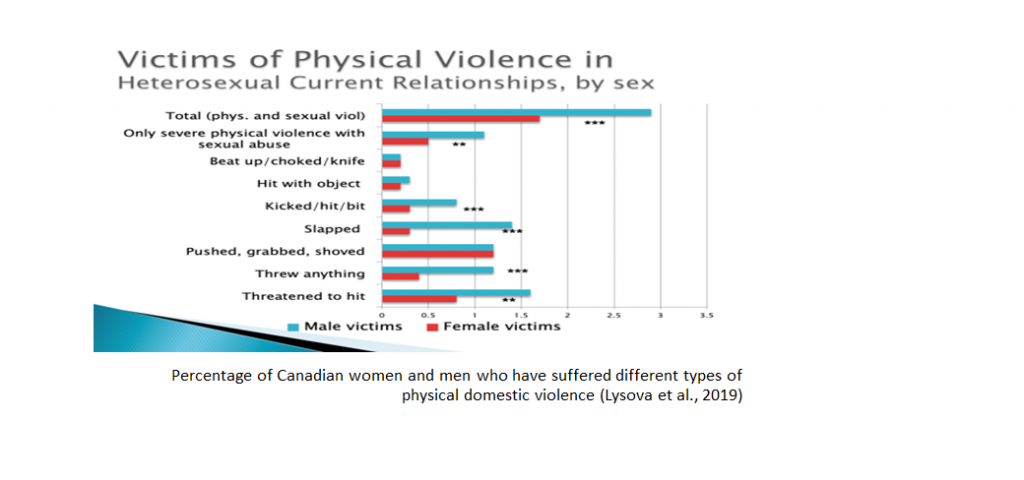

To properly assess victimization it is vital to have protocols that contain specific questions about how violence is perpetrated which would be helpful to show how intimate partner violence affects all genders. For instance, the General Survey Data (2016), used as a tool to understand differences among victims of physical violence in heterosexual relationships, shows that men experience physical violence at a greater or equal rate as women (Lysova et al., 2019). Figure 18.1 below reports that there are more male targets (victims) in severe physical violence with sexual abuse, hitting with an object, kicking, slapping, throwing things and slapping in heterosexual relationships. The same figure shows that being beaten/choked/knifed and being pushed/ shoved/grabbed are equally prevalent for men and women in heterosexual relationships. Although this study contradicts previous research that indicated that women were the majority of victims, it is critical to acknowledge that regardless of incidence rates, any group of people can experience relationship violence and nobody should have to suffer in silence.

Figure 18.1 – Victims of Physical Violence, by sex

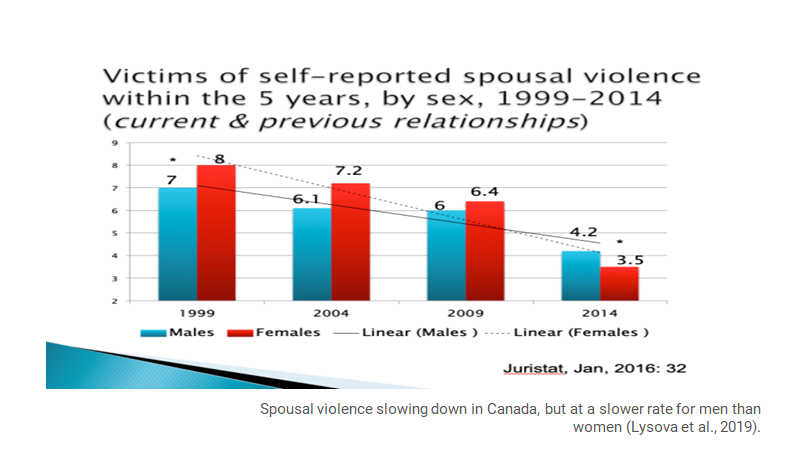

Statistical analyses have their place and they reveal important information. However, researchers have to be cautious with selective bias. What is essential is that innocent people are being abused, traumatized, and need healing. Additionally, all offenders must be identified, held accountable and provided with the resources to help understand and address the behaviour. Issues related to identifying, recognizing, and providing appropriate support to male victims are observed in the graph below (Lysova et al., 2019). As studies and support services seem to be effective in reducing cases of relationship violence among women, male victims do not receive the same support. Intimate partner violence among men decreases at a slower rate suggesting important gaps in the knowledge and strategies to address violence among this population group. This slower decrease may be because men do not report and there are not many services specific to male survivors (as shown in Figure 18.2).

Figure 18.2 – Victims of Self-reported Spousal Violence

In relationship violence, there are fewer studies on men as survivors and most studies address men as the perpetrators. Although though violence against men has been identified since the 1980s there is less media attention paid to men as victims than to women (Hines & Douglas, 2009). Hines & Douglas, (2010) reporting on the US note, “that best population-based surveys show that between 25% and 50% of victims of IPV (intimate partner violence) are men” (p. 575). Analysis of the 2014 Canadian General Social Survey on Victimization in Canada found “2.9% of men and 1.7% of women reported experiencing physical and/or sexual IPV” (Lysova et al., 2019, p. 206). “The odds of men reporting that they were physically assaulted were 1.7 times that of women (X 2 = 12.7, p< .001) and the odds of men reporting that they experienced severe physical assault were 2.1 times that of women (X 2 = 9, p< .01)” (Lysova et al., 2019, p.208 ). “Men were more like to report being slapped, kicked, bit, hit, threatened with battery, or that something dangerous was thrown at them” but there was no significant difference in experiencing violence with the current heterosexual partner between men (42%) and women (39%) (Lyvosa et al., 2019, p.208). Police reported rates are contrary to this data, stating 79% of the cases are IPV against women (Burczycka & Conroy, 2018).

Intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetrated by women against a male partner is a topic of intense debate. Some theorists seem resistant to accept the fact that women can also be offenders of intimate partner violence, arguing that when women perpetrate violence, it is to act in self-defence (Houry et al., 2008; Kernsmith, 2005; Muftic et al., 2007). In this view, researchers turn once again to the view that “social power structures are reflected in interpersonal relationships” and men, as the socially dominant gender, are the ones who misuse this power by trying to oppress and become dominant (Hines et al., 2007, p.63). As the notion of power and dominance exerted by some male individuals towards a female partner is mentioned in many studies of IPV, this theory is not effective in explaining the complexity of intimate relationships and the dynamics that involve relationship violence perpetrated among any group of people. With a diverse population and types of relationships, some researchers have tried to propose theories that might help the understanding of RV. For instance, Johnson (2005, 2010) suggests that intimate partner violence is related to three main situations:

- One of the partners (male or female) feels the desire to take control over their partner

- Resistance to partner’s attempts of control

- Stressful daily life situations leading to violent behaviours

Johnson (2010) categorizes these circumstances as intimate terrorism, situational couple violence, mutual violent control and violent resistance.

- Intimate terrorism denotes a partner’s attempts to control with the intention to dominate by employing negative coercive behaviours like emotional abuse (e.g., isolation, threats, humiliation) physical and sexual abuse against the partner.

- Situational couple violence refers to episodes of violence that occur due to conflict triggered by situations of everyday stress or discussions that might escalate to violence (Johnson & Leone 2008, p. 6).

- Lien & Lorentzen (2019) propose that mutual violent control and violent resistance denote two different patterns that can follow intimate terrorism and situational couple violence. While in mutual violent control, both partners are violent and attempt to exert control over each other, violent resistance refers to physical violence as a self-defence act that results from experiencing intimate terrorism.

Johnson’s typology was initially connected to the notion that women experience IPV more frequently than men. Although different ways of counting IPV lead to different statistics on sex and victimhood (see chapter 5 for discussion of CTS) other studies show that Johnson’s typology can be helpful when analyzing IPV among males (Hines & Saudino, 2003).

Lysova, Dim & Dutton (2019) analysis of a Canadian National Survey of Victimology found that of those reporting victimization 22% of male victims and 19% of female victims of IPV reported that they had experienced severe physical violence along with high controlling behaviours (Lysova et al. 2019). This survey found that of those reporting violence 50% were men but Lysova et al. (2019) surmise that as physical violence against men by women can be less injurious than vice versa that male victimology, outside of such surveys, is less visible as it results in fewer hospital visits or police reports. Even when the victimization of males is reported the outcomes may not recognize the violence. In Scotland, in ‘2000 those who perpetrated domestic abuse against men were slightly less likely to have had their acts deemed criminal by the Scottish Police than those who perpetrated domestic abuse against women’ Gadd et al., 2002, p.vi). In addition, those who perpetrated IPV against men were also a little less likely to be referred to the courts (Gadd et al., 2002).

In a report conducted for the Scottish Executive David Gadd et al. (2002) attempted to explain the discrepancies between the number of men who self-reported being survivors in the Scottish Crime Survey in 2000 with the considerably smaller number of reports men made to the Scottish police. Some of the discrepancies were that a number of men completing the survey misread or misunderstood ‘domestic violence’ (the term used in this report) and reported on physical violence from other sources. However, the authors also concluded that:

Relative to female victims of domestic abuse, male victims, in general, were less likely to have been repeated victims of assault, to have been seriously injured, and to report feeling fearful in their own homes. These factors, coupled with the embarrassment many male victims felt, helped explain the infrequency with which male victims of domestic abuse came to the attention of the Scottish Police. Some of the male victims of domestic abuse identified in the Scottish Crime Survey 2000 were also assailants and therefore did not wish to draw themselves to the attention of the police. (Gadd, et al. 2002, p.vi)

These factors, further invisibalize the existence of male survivors of IPV.

Gadd et al. (2002) also conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 22 men who did report being male survivors of IPV, which they divided into four categories:

- Primary instigators – they began the violence – n=1

- Equal combatants – those who reported being equally responsible – n=4

- Retaliators – those who used violence back but did not instigate it – n=8

- Non-retaliatory victims – n=9

Even amongst the nine non-retaliatory victims, not all saw their situation as being domestic violence, for example:

Vince’s ex-girlfriend had smashed a glass into his wrist and had punched him. In hindsight, Vince considered these incidents ‘funny’, although he did not see them this way at the time. Likewise, Zac belittled the actions of the three partners he claimed had abused him. Zac described the behaviour of these three women as ‘amusing’.. (Gadd et al., 2002, p.42)

It may be that Zac’s and Vince’s responses stem from their understanding of their own masculinity, to see violent acts as ‘funny’ or ‘amusing’ is an attempt to diminish the severity, the threat and the violence of these actions. To show that as men they are capable of handling such incidences. If this is the case, we also have to factor in men’s notion of proper masculine behaviour (that includes being in control, of being strong, of being social) when explaining why some men, like some women, do not perceive their victimhood as part of a systemic system of violence. Gadd et al. (2002: pvii) note:

the qualitative research upon which this report is based shows that domestic abuse against men can take life-threatening forms and can have lasting effects. Some of the male victims interviewed experienced a range of abuses from their partners. This abuse took emotional, financial, and physical forms. However, many of the male victims in our sample described their partners’ abuses as relatively rare and inconsequential in the longer term. Few men cited abuse as reasons for having left their partners. Abuse frequently occurred when relationships were in crisis or ‘breaking up’, and/or when access to children had to be negotiated between partners who were living apart.

A Norwegian study (Lien & Lorentzen, 2019) provides some more information on men as victims. Lien & Lorentzen conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 28 men recruited, primarily, from men accessing family protection services, attending crisis centres and from adult survivors of child sexual abuse and incest. In total, there were 18 interviews with men who had not suffered child sexual abuse. Of these 18, 1 grew up in a violent home but had not suffered IPV; 3 reported IPV from their male partners and the remainder are survivors of IPV from female partners. Although this is a small study it is useful as it provides information on the experiences and perspectives of men who have survived IPV. The study included Norwegian and foreign-born men. Of the Norwegian men, they tended to be young with some post-secondary education (i.e., about three years of university-level education) but the foreign-born men were not so educated.

Lien & Lorentzen (2019) found that their respondents reported being subjected to systemic harassment and humiliation by their female partners, which are characteristics of psychological dominance. These male survivors reported withdrawing themselves from their usual social circles, become isolated, and lonely (Lien & Lorentzen, 2019). The men in this study affirmed that they could handle the violence, could resolve the problem and denied that their circumstances are part of systemic violence (Lien & Lorentzen, 2019, p.79) matching the attitudes of Zac and Vince detailed above.

So, it can be seen that even when aggression occurs to men from their intimate partners they do not perceive it as something that deserves to be reported to the police. In reported cases, men rarely describe intimate partner violence as an act that invokes fear and control, even when there is an explicit mention of aggressive behaviours. Furthermore, police reports show that women who do aggress are more likely to use a weapon against the intimate male partner (Dim, 2017; Hester, 2012).

Incidence Rates

There are debates regarding variations in incidence rates, as shown by Gadd et al. (2002). These variations can be due to differences in what is being counted and, as shown above, can also be from inaccurate reporting. However, US figures show that 1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men have experienced intimate partner violence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2017) and these are consistent with surveys from other Western societies. In Canada, national surveys show that men represent 20% of IPV survivors (Statistics Canada, 2011). However, some studies contradict these estimates. Dim (2017) suggests that intimate partner violence is experienced at similar rates by females and males, arguing that the difference lies in the forms of violence and not in the number of cases. For instance, sexual violence in cases of IPV appears to affect more women and girls, while physical violence, in its many forms, appears to be higher amongst men. Similarly, a meta-analysis shows that in incidents with women as the offender, psychological and physical violence seems to be the most prevalent forms of IPV (Williams et al., 2008). Physical assault (e.g., pushing, slapping, punching, and using a weapon to cause severe harm) represents 87% of IPV against males in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2018). This high figure may also be due to the fact, as discussed above, less violent incidences of IPV may not be viewed as violence by male survivors.

Barriers to Seeking Help

Although intimate partner violence is more prevalent and severe for women, it is also perpetrated against men. Men may suffer domestic violence from heterosexual relationships, same-sex relationships, former partners or other family members. A systematic review was conducted on help-seeking experiences of male survivors of domestic violence by Huntley et al., (2019). They described barriers faced by males in seeking help and expertise of services. Trying to seek and receive help among male IPV victims is challenging, and those who exhibit negative psychological symptoms experience difficulty finding support services (Powney, 2019). Also, they experience distressing and secondary victimization as professionals and services are not prepared to provide support to this population group (Hines & Douglas, 2014; Tsui, 2014).

Barriers to Seeking Help

Fear of disclosure – shame, denial and embarrassment, fear of not being believed, nowhere to go and fear of losing children

Challenge to masculinity – stigma, fear of not being believed

Commitment to relationship – want to stay in the relationship but want abuse to stop

Diminished confidence/despondency – decreased confidence and depression/Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, reported abuse on open-ended surveys but did not disclose to anyone

Invisibility/perception of services – not aware of services or thought they were inappropriate

(Hines & Douglas, 2014)

Male Survivor Experience (Huntley et al., 2019)

Initial contact occurred following a crisis when a sense of urgency to report occurred and family members were generally viewed as supports.

Confidentiality or private space especially in healthcare settings is needed, and clergy are seen as those who may keep privacy by some

Appropriate professional approach- more comfortable with a consistent female professional

Inappropriate professional approaches- lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) survivors stated that service was heterosexual focused and professionals lacked understanding, and heterosexual men experienced both negative and positive experiences from the police.

Sexual Violence

We do have some basic facts about men as victims:

- Rape of men more commonly committed by heterosexual men (McMullen, 1990)

- Sexual orientation of victims evenly distributed

- 66% of gang assaults on men also perpetrated by heterosexual men (Hodge & Canter, 1998)

- Female perpetrators involved in 40% of sexual assaults on males (Coxell et al., 2000)

Male survivors of sexual assault are also more likely (than women) to be victims of greater physical trauma, held in captivity for longer and be raped by multiple assailants, sometimes more than once (Groth, 1980). Rapists of men also tend to use weapons more than those who rape women (Donaldson, 1990) possibly due to the fact that the perpetrator and victim may be closer in physical strength than a man raping a woman or child. As already mentioned there are few services for male sexual assault survivors than for women and this, in combination with ideas around appropriate masculinity, leads to men being more likely to cope through denial and control – which makes them more prone to future psychiatric problems and further reduces help-seeking behaviours (Mezey, 1987).

Sexuality Abuse is a term that has come into more common use, and it mainly describes any behaviour that undermines the integrity of the individual’s sexual identity or sexual safety. Sexuality abuse includes not only actions that are traditionally viewed as sexual abuse (i.e. criminal acts) but also covert sexual actions, not often recognized either by the courts or by the general population. Some examples are derogatory comments of a sexual nature, leering looks, age-inappropriate exposure to sexual information or imagery, or the lack of appropriate information. Although these and other examples may not result in criminal charges, nor be intentional, they may nevertheless result in long-term disturbance for the victim.

Victims and offenders of sexual abuse are increasingly seen as including a broader range of individuals. While it was once believed that a larger percentage of survivors are female than are male, recent studies indicate that the numbers are not as disparate as previously assumed. Sexual abuse of males of all ages is not rare. Statistics may be misleading if taken at face value: statements such as “…the majority of victims are female…” minimize the extent of victimization of males, or “…offenders are predominantly male…” may result in one overlooking female offenders.

Besides intimate partner violence, males experience other forms of relationship violence. Statistics Canada (2011) indicates that men are more vulnerable to violence perpetrated by friends and acquaintances (73,111 number of cases), and casual acquaintances (50,544 number of cases). “Physical assault was more common among male victims (87% versus 74% of female victims)… It was almost twice as common for weapons to be present in intimate partner violence involving male victims as when the victim was female (23% versus 12%), a finding consistent for both spousal and dating violence” (Statistics Canada, 2018). When men are victims of p[hysical violence it is often more severe than for women (though not for transwomen) and men are more likely than women to be victims of the most serious violent acts such as homicide (WHO, 2017).

IPV in Gangs

Gangs are critical social groups in which relationships violence occurs between gang members. Gangs have generally been classified as a group of people that engages, either individually or collectively, in illegal and non-political acts of violence. Although there are many arguments to better elaborate and expand this definition, researchers argue that there is a lack of adequate sociological analysis and low consensus on how to improve the meaning of gangs (Jingfors et al., 2015). The World Health Organization classifies gangs as an act of collective violence which refers to “the instrumental use of violence by people who identify themselves as members of a group—whether this group is transitory or has a more permanent identity—against another group or set of individuals, to achieve the economic or social objective” (WHO, 2002). Contrary to many countries in which gangs are associated with poverty and marginalization, gang groups in Canada are allied to affluence and status (Jingfors et al., 2015). The Canadian Criminal Code (section 467.1) defines gangs as:

an organized group of three or more, that as one of its main purposes or main activities is the facilitation or commission of one or more serious offences, that, if committed, would likely result in the direct or indirect receipt of a material benefit, including a financial benefit, by the group or by anyone of the people who constitute the group and excluding cases of a single offence (Canadian Criminal Code R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46).

In British Columbia, gangs are involved in illegal activities like drug trafficking, firearms sales, extortion and the sex trade. These activities are all done with the intention to make a profit, and gang leaders have to find ways to launder their profits. These strategies often “present opportunities” to those who want to get involved with gang groups. The need to make a profit leads to territorial disputes among different gang groups that frequently lead to extreme acts of violence (Dandurand et al., 2019). Gangs often target male and female youth who get involved in the circles of violence in order to earn money and get recognition from gang members. Despite the presence of law enforcement bodies targeting gangs’ activities gangs are difficult to suppress and helping young people extricate themselves from gangs is difficult. Historically, street gangs and business-oriented gangs have been organized along with a shared identity within specific neighbourhoods and provide a sense of belonging for their members. Therefore, finding ways to address this issue and prevent involvement should include a multifactorial approach, one that considers ethnicity and culture (McConnell, 2015).

Although gang-related homicides in Canada are relatively low compared to the US, gangs impact many communities and families, especially in western regions of Canada like British Columbia (BC). Young individuals are at the highest risk of becoming involved with gangs. Wortley & Tanner (2004) study shows the following significant risk factors.

-

-

- Low attachment to the community

- Over-reliance on anti-social peers

- Poor parental relationship

- Alcohol and drug abuse

- Poor educational or employment potential

- A need for recognition and belonging

-

Even though gang activities have been linked to sexual exploitation of girls, those who are often targeted are boys and young males. Boyce and Cotter (2013) suggest that youth gang members are connected to a great number of criminal behaviours like drug trafficking, frauds, assaults with weapons and homicides.

Table 18.4 – Programs in Canada

| Agency | Project | Summary |

| BC Society for Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse | BC Society for Male Survivor of Sexual Abuse | This is the only organization in British Columbia that focuses on male survivors. The British Columbia Society for Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse (BCSMSSA) is a non-profit society established to provide therapeutic services for males who have been sexually abused at some time in their lives. They offer individual and group therapy to men who had experienced sexual abuse. |

| Moving Forward Family Services | Counselling Services | This initiative was started by NEVR member Gary Thandi. They provide low barriers counselling support for survivors and families in the Vancouver Lower Mainland. Their head office is in Surry. |

| Canadian Centre for Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse | Healing, education, advocacy and research centre. |

It has a list of treatment centres for male survivors of sexual abuse across Canada and links to resources such as books and podcasts. They are building a centre in Calgary, Alberta. |

| Public Safety Canada | Crime Prevention through the Strengthening of Youth, Families and the Community Project | This initiative was started in 2014 in response to high incidence rates of violence among youth in Prince George, Canada. The project uses the Strengthening Families framework that aims to enhance parents’ and child communication and relationships, reduce alcohol and drug use among youth, and teach social skills. |

| National Gang Center | Comprehensive Homicide Initiative | This initiative engages legal and police forces to investigate and enforce the law in areas of high homicide incidence in California, US. The initiative involves the apprehension of guns and drugs and the incarceration of criminals. The program uses the OJJDP Comprehensive Gang Model as a tool to understand risk factors, community vulnerability and support to promote safety. |

| Caring Dads | Caring Dads Initiative | Caring Dads is focused to support change practices to better include fathers in efforts to enhance the safety and well-being of their children. |

Table 18.5 – Programs outside Canada

| Agency | Project | Summary |

| After Silence | Online chat group |

It is an online support group for survivors with resources for male survivors |

| RAINN | Sexual Assault of Men and Boys |

It is an online support group for male survivors of sexual assault with resources. |

| ManKind Initiative | Males Victims of Domestic Abuse | This initiative serves men and their family members and friends who would like to find information for someone else. As an additional resource, MVDA provides training to police officers, hospital staff, local council, counsellors, and welfare community groups. |

| Abused Men in Scotland | Abused Men in Scotland | The initiative provides helpline support and face to face meetings during weekdays from 9 am to 4 pm to all UK areas. |

References

1 in 6. (2018). Survivors of Sexual Abuse and Assault Reveal an Important Truth. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2p06x-yumc0

Badenoch, K. (2015). Silent suffering, supporting the male survivors of sexual assault. GLA Conservatives. https://www.survivorsuk.org/press-release/gla-report-silent-suffering-supporting-the-male-survivors-of-sexual-assault/

Boyce, J., & Cotter, A. (2013). Homicide in Canada, 2012. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/131219/dq131219b-eng.pdf?st=QMJjOAFJ

Bradley, H. (2013). Gender: Key concepts. Cambridge.

British Columbia Society for Male Survivor of Sexual Abuse. (2020). Males survivors of sexual abuse: in churches, sports fields and their homes. https://bc-malesurvivors.com/articles/

Burczycka, M., & Conroy, S. (2018). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2016. Statistics Canada Catalogue. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54893-eng.pdf?st=U_mbIfK7

Canadian Criminal Code R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Carpenter, R.C. (2006). Recognizing gender-based violence against civilian men and boys in conflict situations. Security Dialogue 37(1), 83-103.

Carter, J. (2015). Patriarchy and violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9978), e40-e41.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf

Cramer, E. P., & Plummer, S. B. (2009). People of color with disabilities: Intersectionality as a framework for analyzing intimate partner violence in social, historical, and political contexts. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(2),162-181.

Dandurand, Y., McCormick, B., & Bains, S. (2019). Developing strategies on: Violence prevention and community safety in Abbotsford BC. South Asian Research Fellowship Report. University of the Fraser Valley, South Asian Studies Institute.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Garcia-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., LIm, S., Bacchus, L. J., Engell, R. E., Rosenfeld, L, Pallitto, T., Vos, T., Abrahams, N., & Watts, C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), 1527-1528.

Dim, E. E. (2017). Recent trends in physical and psychological intimate partner violence against men in Canada: A mixed-methods study. University of Saskatchewan. https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/8069/DIM-THESIS-2017.pdf

Donaldson, S. (1990) Rape of Males. Encyclopedia of Homosexuality. Garland.

Ferrales, G., Nyseth Brehm, H., & Mcelrath, S. (2016). Gender-based violence against men and boys in Darfur: The gender-genocide nexus. Gender & Society, 30(4), 565-589.

Gadd, D., Farrell, S., Dallimore, D., & Lombard, N. (2002) Domestic Abuse Against Men in Scotland, Scottish Executive Central Research Unity, Edinburgh. https://www2.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/46737/0030602.pdf

Hester, M. (2013). Who does what to whom? Gender and domestic violence perpetrators in English police records. European Journal of Criminology, 10(5), 623-637. DOI: https://doi-org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.1177/1477370813479078

Hines, D. A., Brown, J., & Dunning, E. (2007). Characteristics of callers to the domestic abuse helpline for men. Journal of Family Violence, 22(2), 63-72.

Hines, D. A., & Douglas, E. M. (2009). Women’s use of intimate partner violence against men: Prevalence, implications, and consequences. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(6), 572-586.

Hines, D. A., & Douglas, E. M. (2010). Intimate terrorism by women towards men: Does it exist?. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 2(3), 36.

Hines, D., & Douglas, E. (2014). Health problems of partner violence victims: Comparing help-seeking men to a population-based sample. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48, 136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.022

Hines, D.A., & Saudino, K.J. (2003). Gender differences in psychological, physical, and sexual aggression among college students using the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales. Violence and Victims, 18, 197-218. http://wordpress.clarku.edu/dhines/files/2012/01/HINES-Saudino-2003_GENDER-DIFFERENCES.pdf

Houry, D., Rhodes, K. V., Kemball, R. S., Click, L., Cerulli, C., McNutt, L. A., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Differences in female and male victims and perpetrators of partner violence with respect to WEB scores. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1041-1055. doi:10.1177/0886260507313969

Huntley, A. L., Potter, L., Williamson, E., Malpass, A., Szilassy, E., & Feder, G. (2019). Help-seeking by male victims of domestic violence and abuse (DVA): A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open, 9(6), e021960.

Jingfors, S., Lazzano, G., & McConnell, K. (2015). A media analysis of gang-related homicides in British Columbia from 2003 to 2013. Journal of Gang Research, 22 (2), 1-17.

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence against Women, 12(11), 1003-1018.

Johnson, M. P. (2010). A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Northeastern University Press.

Johnson, M. P., & Leone, J. M. (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National violence against women survey. Journal of family issues, 26(3), 322-349.

Lewis, D. A. (2009). Unrecognized victims: Sexual violence against men in conflict settings under international law. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 27.

Lien, M., I., & Lorentzen J. (2019). Men’s experiences of violence in intimate relationships. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03994-3

Lysova, A., Dim, E. E., & Dutton, D. (2019). Prevalence and consequences of intimate partner violence in Canada as measured by the National Victimization Survey. Partner Abuse, 10(2), 199-221.

Marchbank, J., & Letherby, G. (2014) Introduction to Gender: Social science perspectives. Routledge, London.

McConnell, K. (2015). The Construction of the Gang in British Columbia: Mafioso, Gangster, or Thug? An axamination of the uniqueness of the BC gangster phenomenon. Unpublished dissertation. https://arcabc.ca/islandora/object/kora%3A279

Meyer, D. (2010). Evaluating the severity of hate-motivated violence: Intersectional differences among LGBT hate crime victims. Sociology, 44(5), 980-995.

Meyer, D. (2015). Violence against queer people: Race, class, gender, and the persistence of anti-LGBT discrimination. Rutgers University Press.

Muftic, L. R., Bouffard, J. A., & Bouffard, L. A. (2007). An exploratory study of women arrested for intimate partner violence: Violent women or violent resistance? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 753-774. doi:10.1177/0886260507300756

Network to Eliminate Violence in Relationships. (2019). Community champion tool kit: Responding safely to situations of relationship violence. https://www.kpu.ca/sites/default/files/NEVR/Community%20Champions%20Toolkit.pdf

Powney, D., & Graham-Kevan, N. (2019). Male victims of intimate partner violence: A challenge to the gendered paradigm. In The Palgrave Handbook of Male Psychology and Mental Health, 123-143. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Riccardi, P. (2010). Male rape: The silent victim and the gender of the listener. Primary care companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(6).

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex Couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Sidanius, J., & Veniegas, R. C. (2013). Gender and race discrimination: The interactive nature of disadvantage. In Reducing prejudice and discrimination, 57-80. Psychology Press.

Statistics Canada (2011). Homicide in Canada. http://capg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Homicide_in_Canada_2011.pdf

Statistics Canada (2018). Family violence in Canada: A statistics profile, 2016. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54893/tbl/tbl3.3-eng.htm

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

Thureau, S., Le Blanc-Louvry, I., Gricourt, C., & Proust, B. (2015). Conjugal violence: a comparison of violence against men by women and women by men. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 31, 42-46.

Todahl, J. L., Linville, D., Bustin, A., Wheeler, J., & Gau, J. (2009). Sexual assault support services and community systems: Understanding critical issues and needs in the LGBTQ community. Violence Against Women, 15(8), 952-976.

Tsui, V. (2014). Male victims of intimate partner abuse: Use and helpfulness of services. Social Work Advance, 59, 121–130. doi: 10.1093/sw/swu007.

United Nations. (1996). Clarification of the term gender. In Women’s Initiative for Gender Justice. http://iccwomen.org/resources/gender.html

Williams, J. R., Ghandour, R. M., & Kub, J. E. (2008). Female perpetration of violence in heterosexual intimate relationships: Adolescence through adulthood. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9, 227-249. doi:10.1177/1524838008324418

World Health Organization. (2002). World report on violence and health: Summary. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf

Wortley, S., & Tanner, J. (2004). Social groups or criminal organizations? The extent and nature of youth gang activity in Toronto. From enforcement and prevention to civic engagement: Research on Community Safety, 59-80.