Chapter 14: Creating Healthy Relationships How to Change to Reduce and Eliminate Relationship Violence

Balbir Gurm and Glaucia Salgado

Key Messages

- Based on different theories, there may be different actions that can be taken to reduce the acceptance of relationship violence. Some actions we recommend are:

- Make a personal commitment to change. Take the pledge at all our rallies and events.

- Highlight personal stories of abuse and impacts on families.

- Promote local helplines and have support for those who want to stop abusing.

- Provide feedback to those that create an environment of safety and equity.

- Establish a national prevention campaign that shows the impact of violence, and normalizes healthy relationships.

- Normalize equitable decision-making among couples.

- Encourage media to describe the impacts of relationship violence.

- Share the stories of survivors in our communities.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollà et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death.

Behavioural Change Models

Relationship violence is a pandemic affecting every country in the world and it needs to be addressed. How can we change individuals/societies and communities? There are a number of behavioural change models that can be used, and a summary can be found below (Dyson & Flood, n.d.).

-

-

- The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) argues that lasting attitude and behaviour change occurs when participants are motivated to hear a message, able to understand it and perceive the message as relevant to them. For example, if I believe what you are saying is relevant to me, I will listen carefully.

-

-

-

- The Social-Ecological Model suggests that the problem of violence against women is essentially one of culture and environment, rather than one of the psychological or biological deficits in individuals. For example, violence against women continues not because of genetic or mental health issues, but because society accepts it.

-

-

-

- The Social Norms Approach suggests that the majority culture, or normative environment, may support an individual’s beliefs and behaviours and seeks to achieve change through social marketing. This approach aims to shift men’s perception of social norms by revealing the extent to which other men also disagree with violence or are uncomfortable with common norms of masculinity. For example, if other men or people think what you are doing is wrong, you are less likely to do it. In some cultures, the phrase “what will people say” is used to keep survivors from reporting to keep the relationship abuse a private matter.

-

-

-

- The Community of Responsibility Model is based on the premise that everyone in a community has a role to play in ending violence against women (Dyson & Flood, n.d. p 16-17). For example, it is not an issue just for men, women, or children but for every single one of us even if we are not involved in the abuse cycle.

- The Appreciative Inquiry model is based on the premise that we need to focus on the positive and amplify it. For more details click here.

-

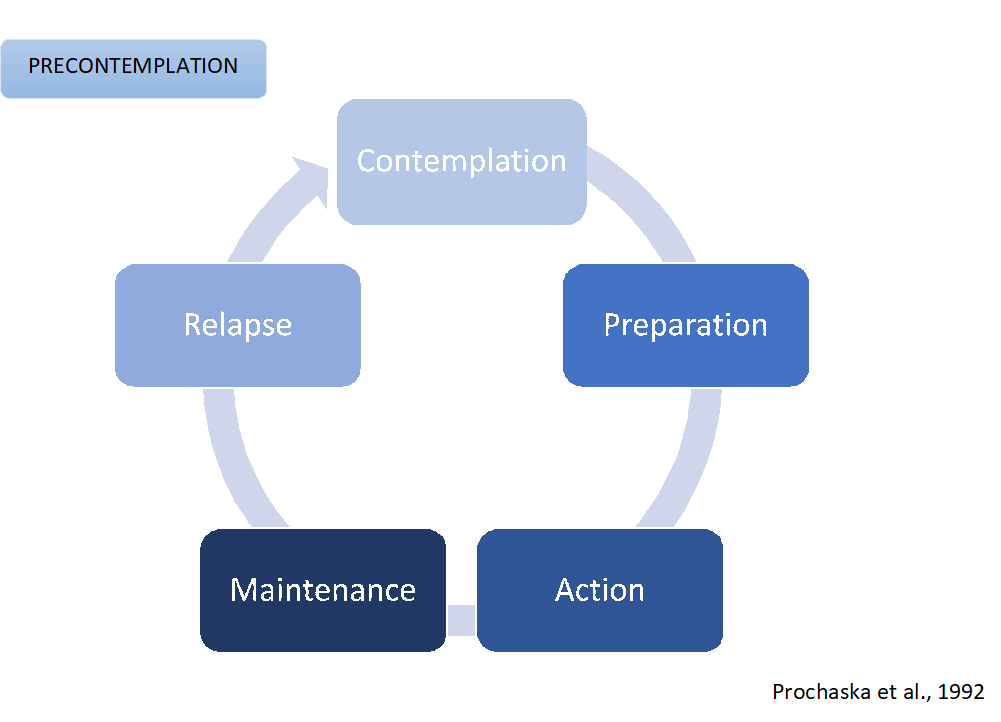

We believe change needs to be addressed using multiple approaches. There are many other theories that can be utilized to implement personal/family and community change. The Transtheoretical Model of planned change was developed by James Prochaska and colleagues (Prochaska et al., 1992) from health psychology. It contains more than 20 years of research documenting its success. It is highlighted below. This model has 6 steps that repeat making it a cyclical model.

Figure 14.1 – Process of Change

- Precontemplation (Not yet acknowledging that there is a problem behaviour that needs to be changed)

- Contemplation (Acknowledging that there is a problem but not yet ready or sure of wanting to make a change)

- Preparation/Determination (Getting ready to change)

- Action/Willpower (Changing behaviour)

- Maintenance (Maintaining the behaviour change) and

- Relapse (Returning to older behaviours and abandoning the new changes) (Prochaska et al., 1992)

From years of research, it is now believed that there are 10 processes that help individuals move through change. Gurm (n.d.) adapted these processes that were originally created for anti-smoking to anti-violence programs organized. These processes are listed under the heading of experiential or behavioural (see below). They were retrieved from The Stages of Change pdf where more details can be found.

Processes of Change: Experiential

1. Consciousness Raising [Increasing awareness]

I recall the information I had received on the prevalence of the issue and some signs and symptoms of abuse.

2. Dramatic Relief [Emotional arousal]

I react emotionally to the personal stories of abuse.

3. Environmental Reevaluation [Social reappraisal]

I consider the view that abuse in its different forms is toxic, it is a serious health issue across the lifespan.

4. Social Liberation [Environmental opportunities]

I find society changing in ways that make it easier for survivors to come forward. The #metoo has helped.

5. Self Reevaluation [Self reappraisal]

Figure 14.2 – Process of Change Experimental (adapted)

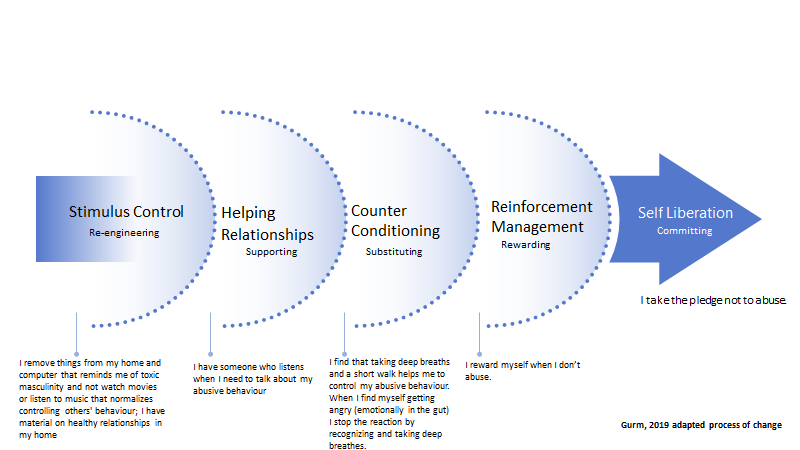

II. Processes of Change: Behavioural for male offenders in heterosexual relationships

6. Stimulus Control [Re-engineering]

I remove things from my home and computer that reminds me of toxic masculinity and I do not watch movies nor listen to music that normalizes controlling others’ behaviour; I have material on healthy relationships in my home.

7. Helping Relationship [Supporting]

I have someone who listens when I need to talk about my abusive behaviour.

8. Counter Conditioning [Substituting]

I find that taking deep breaths and a short walk helps me to control my abusive behaviour. When I find myself getting angry (emotionally in the gut) I stop the reaction by recognizing and taking deep breaths.

9. Reinforcement Management [Rewarding]

I reward myself when I don’t abuse.

10. Self Liberation [Committing]

I take the pledge not to abuse.

Figure 14.3 – Process of Change Behavioural (adapted)

These steps are mediated by the characteristics of those involved. Each one of us can do this on a personal level.

Appreciative Inquiry

NEVR uses the appreciative inquiry (AI) approach to address relationship violence. Click here for a quick overview of AI. The AI model originally had 4 steps and was developed for organizations but now has been expanded to 5 steps, and it can be applied to individuals, organizations and communities. Click here to read about the 5D model.

1. Define – we have explained the issue of RV in multiple chapters

2) Discover – we centre human rights legislation and socio-environmental framework

3) Dream – we identify the goal, what we envision

- Governments work with media to create positive messages about healthy communication so they are abundant.

- Everyone is treated with dignity and respect and not traumatized.

4) Design – we suggest actions

- Make resources open access and plan to train each person to be a community champion (this is what we are doing)

- Create a central repository for all resources similar to the COVID-19 response

- Governments and non-profit organizations work together to ensure adequate services to deal with relationship violence exist (design)

- Governments at all levels to work together to create national campaigns on relationship violence to run over a generation (25-30 years) (design)

- Communities are made aware of relationship violence resources (design)

5) Destiny – when we reach our goal, we want to embed the processes

- Keep statistics on RV and share and build on successes

Bystander Training

Bystander training is extremely important, yet there is no standard teaching approach. From the teaching literature, we need to create a signature pedagogy for these programs, for the way we teach is as important as what content we teach. Signature pedagogy’s key principles are:

- Break complex skills into small components in teaching and learning – this can be done by scaffolding and having group members practice components of the skill and then put the complex skill together.

- Be intentional with sequencing – plan and design with the end in mind.

- Team teach – have individuals from different disciplines teach the content to show perspectives – for example, with peer teaching, you could have three people with a diversity of gender identity, race, socioeconomic status teach together.

- Active learning and real-world problem solving – provide real-life situations that may be gathered from the group being taught or developed together with service agencies. This will allow participants to mimic the situations that they may see.

- Context – the social, biological and emotional environment is important. Need to ensure cultural safety and intersectionality and provide food at workshops.

- Learning environment – need to ensure that the rationale of all elements of the above (1-5) are explained. Learners need to understand why design and delivery are so important. (Adapted from Gurung et al., 2009 by author, Balbir Gurm for this chapter).

Human Rights Education

Human rights is a theme for RV as it is a human rights violation; it is a social justice concern. The United Nations Global Programme for the Implementation of the Doha Declaration (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC) created education materials on social justice. NEVR member, Yvon Dandurand, was part of the United Nations Team involved in the development of these modules that were created using the best available evidence and expert knowledge. The modules provide lectures, slides, and in-class exercises for university faculty to use free of charge to combat injustices, access the modules here.

Human Rights Education (HRE) is a lifelong process for all. It is an important contributor to the prevention of RV and early intervention. This is particularly true for children and youth, where they learn peaceful problem-solving, relationship skills and boundaries, during their formative development periods. Access to HRE provides an opportunity to develop skills and attitudes that support healthy relationships or to unlearn negative behaviours/attitudes from their own experiences and exposures to RV. The International Centre for Human Rights Education provides toolkits on human rights and focuses on gender-equality. Their Play it Fair toolkit teaches children and positive youth values, such as non-discrimination, respect for diversity, gender equality, inclusion and solidarity are shared and contribute to a sense of common humanity (Equitas, n.d.). All their toolkits can be found here. Discrimination and relationship violence are widespread, deep-rooted, and prevalent in all parts of the world. Equitas helps to strengthen collaboration between women’s organizations and human rights organizations and to encourage decision-makers to respect their obligations related to gender equality. All these toolkits need to be adapted to include minority lenses including gender and sexual diversity and race.

References

Carney, M., Buttell, B. & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Dyson, S., & Flood, M. (n.d.) Building cultures of respect and non-violence: A review of literature concerning adult learning and violence prevention programs with men. https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/-/media/ProgramsandProjects/DiscriminationandViolence/PreventingViolence/RespectResponsibilityReport.pdf?la=en&hash=9FBE28668BBB1B646D168F9C4EC0C281DA6B47D3

Equitas. (n.d.). www.equitas.org

Gurung, R. A. R, Chick, N.L., & Haynie, A. (Eds.) (2009). Exploring signature pedagogies: Approaches to teaching disciplinary habits of mind. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychology, 47, 1102-1114.

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex Couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC. (2019). The Doha Declaration: Promoting a culture of lawfulness. https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/crime-prevention-criminal-justice/module-10/index.html