Violence Is Preventable (VIP) is a free, confidential, school-based violence prevention program for students in grades K-12 that reflects the competencies outlined by Ministry of Education. VIP presentations are delivered by Prevention, Education, Advocacy, Counselling and Empowerment (PEACE) Program counsellors. VIP increases awareness of the effects that domestic violence has on students while connecting those experiencing violence to PEACE program counselling. List of Programs.

Chapter 16: Knowledge about Relationship Violence Against Children

Balbir Gurm and Glaucia Salgado

- Relationship violence against children is known as child abuse and neglect. It includes children who witness abuse and any act or omission by the parent or guardian, resulting in (or likely to result in) harm to the child or youth.

- 1 in 3 children younger than 15 years old has experienced some form of abuse in Canada.

- Several studies and reviews indicate correlations between RV among children and impacts on children’s brain development and bio-psycho-social development from the time of conception throughout their life span.

- Systematic reviews have identified resilience factors in preventing or reducing adverse effects. These resilience factors are secure relationship and emotion regulation, social support, warm and affectionate relationships and cognitive skills and academic achievement.

- Effective prevention programs include parenting programs that strengthen the family unit and minimize harm to the child through education to the parent(s)/caregiver(s) through the introduction of alternative punishment strategies and parental self‐management strategies.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone that has a bond or relationship with the offender. In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, male violence, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology-facilitated coercive control, honour killing, female genital mutilation gang violence and workplace violence. In couples, violence can be perpetrated by women and men in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships where the victim is LGBTQ2SIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, intersex and asexual plus) (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010; Rollè et al., 2018). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, ageism, xenophobia and homophobia. It can span the entire age spectrum. It may start in-utero and end with death.

Relationship Violence Against Children

This chapter provides information on the impact of violence on children and their development. Relationship violence against children is known as child abuse and neglect. RV can have lifelong consequences to the child in terms of their development potential. Information on these adverse childhood effects is provided. Furthermore, resources that can be helpful are described, and these are largely parenting programs that are available. The goal of these parenting programs is to strengthen the family unit and minimize harm to the child through education to the parent(s) and other caregivers.

Definition and Prevalence

Relationship violence against children is known as child abuse and neglect. Child abuse is considered a severe issue that affects children worldwide. Although rates are not always reported, countries like Canada shows that 1 in 3 children younger than 15 years old had experienced some form of abuse (Statistics Canada, 2015). In Canada, for generations, we had the Indian Residential Schools, which forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families. In these residential schools is where many children suffered abuse and neglect. They were not allowed to speak their language or learn about their culture. The children were also isolated from their loved ones and taught the values of the dominant culture. The last residential school did not close until 1996 and Indigenous communities still suffer from the original and intergenerational trauma caused by this system.

In the US the Children’s Bureau (2020) provides the following statistics for 2018:

- Child abuse and neglect: 678,000 children are impacted

- Victim rate is 9.2 victims per 1,000 children

- 26.7 per 1,000 for children up to age one

- 9.6 per 1,000 for girls

- 8.7 per 1,000 for boys

- 15.2 per 1,000 for Indigenous (American Indian & Alaskan Native) children

- 14.0 per 1,000 for African American children

Globally, 25% of adults state they have been abused as children (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). The WHO goes on to state that internationally, 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men acknowledge they were abused as children.

Relationship violence against children is any behaviour or the failure to provide basic needs to someone under 18 years old. It involves an act or omission by the parent or guardian, resulting in (or likely to result in) harm to the child or youth. The forms of child abuse from BC Handbook for Action on Child Abuse and Neglect (Ministry of Children and Family Development, 2017) include:

- Neglect failure to provide food, shelter, primary health care, supervision or protection from risks, to the extent that the child’s or youth’s physical health, development or safety is, or is likely to be, harmed (p. 25)

- Physical abuse is a deliberate physical assault or action by a person that results in or is likely to result in physical harm to a child or youth. It includes the use of unreasonable force to discipline a child or adolescent or prevent a child or youth from harming him/herself or others. The injuries sustained by the child or teenager may vary in severity and range from bruising, burns, welts or bite marks to significant fractures of the bones or skull to, in the most extreme situations, death (p. 24)

- Emotional (or psychological) abuse can include a pattern of scapegoating, rejection, verbal attacks on the child, threats, stalking, insults, or humiliation

- Sexual abuse is when a child or youth is used (or likely to be used) for the sexual gratification of another person. It includes touching or invitation to contact for sexual purposes, intercourse (vaginal, oral or anal), menacing or threatening sexual acts, obscene gestures, obscene communications or stalking, sexual references to the child’s or youth’s body or behaviour, requests that the child or youth expose their body for sexual purposes, deliberate exposure of the child or adolescent to sexual activity or material, and sexual aspects of organized or ritual abuse (p.24)

- Sexual exploitation is a form of sexual abuse that occurs when a child or youth engages in sexual activity, usually through manipulation or coercion, in exchange for money, drugs, food, shelter or other considerations. Sexual activity includes: performing sexual acts, sexually explicit activity for entertainment, involvement with escort or massage parlour services and appearing in pornographic images (p. 24-25)

NEVR’s definition of relationship violence also includes relationships with gangs because they inflict violence on those who are involved with them. Colleagues at the University of the Fraser Valley have written about relationship violence in gang groups of Abbotsford. They discuss how gangs are now more networked and job-specific, and they are only loyal to the money. This relationship violence has led to the deaths of gang members and results in the use of many public resources. The full report is available at Developing strategies on violence prevention and community safety in Abbotsford (South Asian Institute, 2019).

Impact of RV against Children

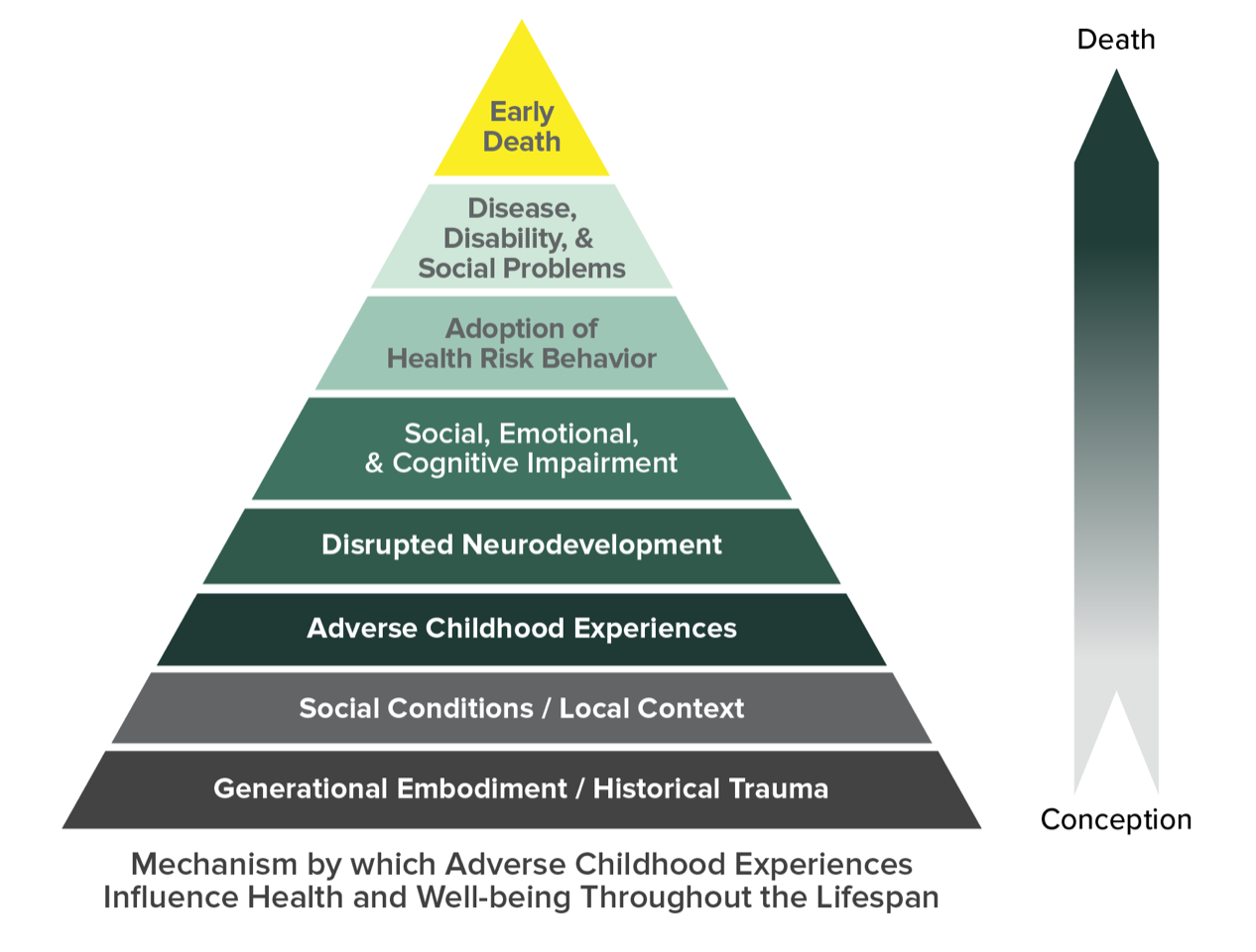

Since the 1990s, significant research has been conducted to show the longitudinal impact of abuse and violence on children’s development. Several studies and systematic reviews provide evidence on the correlations between RV among children (including children who witness abuse) and the impact on children’s brain development and bio-psycho-social development (Mueller & Tronick, 2019; Nocentini et al., 2019; Petersen et al., 2014; Racine et al., 2018; Teicher et al., 2006). Click here to watch a video on the impact of RV on children. The adverse childhood experiences study findings below demonstrate the relationship between childhood adverse events such as experiences of relationship violence against children and health and well-being consequences throughout life. See details from Kaiser Permanent Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). Figure 16.1 explains how generational trauma is transmitted at conception and impacts health and social behaviours through the life span and leads to an early death.

Figure 16.1 – Adverse Childhood Experiences (CDC-Kaiser Ace Study, 2020)

The CDC-Kaiser Permanent Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study collected information from 17,000 individuals in California, US. Questionnaires and surveys are available online, and data continues to be collected by healthcare practitioners. The ACE study included three categories of violence: abuse, neglect and family challenges. The research shows that there is an impact on the child from the time of conception. Also, the longer the time of exposure, the more significant the biopsychosocial implications for the child that can even lead to death. There are sensitive and critical periods of a child’s brain development from birth to age 8 (Figure 16.2). During these years, the brain is most vulnerable and influenced by experiences at home, school and community and has the greatest and long-term impact on how the child’s brain and behaviour are developed (Petersen et al., 2014). Figure 16.2 shows the typical brain development of children ages 0-8, and it is essential to understand that exposure to, and experiences of RV, will have a lifelong impact on children, particularly those under the age of 8 because their brain is forming neuron connections and capacities that are critical for life. The ACE study underscores this developmental issue. Find a summary of the ACE study here. Figure 16.2 shows the typical development for children 0-8 which may be impacted due to trauma from relationship violence.

Figure 16.2 – Typical Developmental Domains for Children Ages 0-8

Findings consistent with the ACE study were found in a systematic review. Mueller & Tronick (2019) suggest that early exposure to relationship violence impacts the brain and behaviour in several ways:

-

- Exposure during pregnancy may lead to:

- Antepartum hemorrhage

- Intrauterine growth

- Preterm delivery

- Fetal death

- Increased cortisol (stress hormone) resulting in high stress and decreased focus for infant

- Exposure during infancy to early childhood (first five years) may lead to:

- Eating problems, sleep disturbances and mood issues, poor overall health, higher irritability, increased screaming and crying

- Increased hyperarousal and fear, aggression and interference with development and sometimes loss of already learnt skills such as toileting in severe RV

- Long-term consequences are liked to PTSD, social and general anxiety, social withdrawal and depression

- Decreased IQ and cognitive function

- Exposure during pregnancy may lead to:

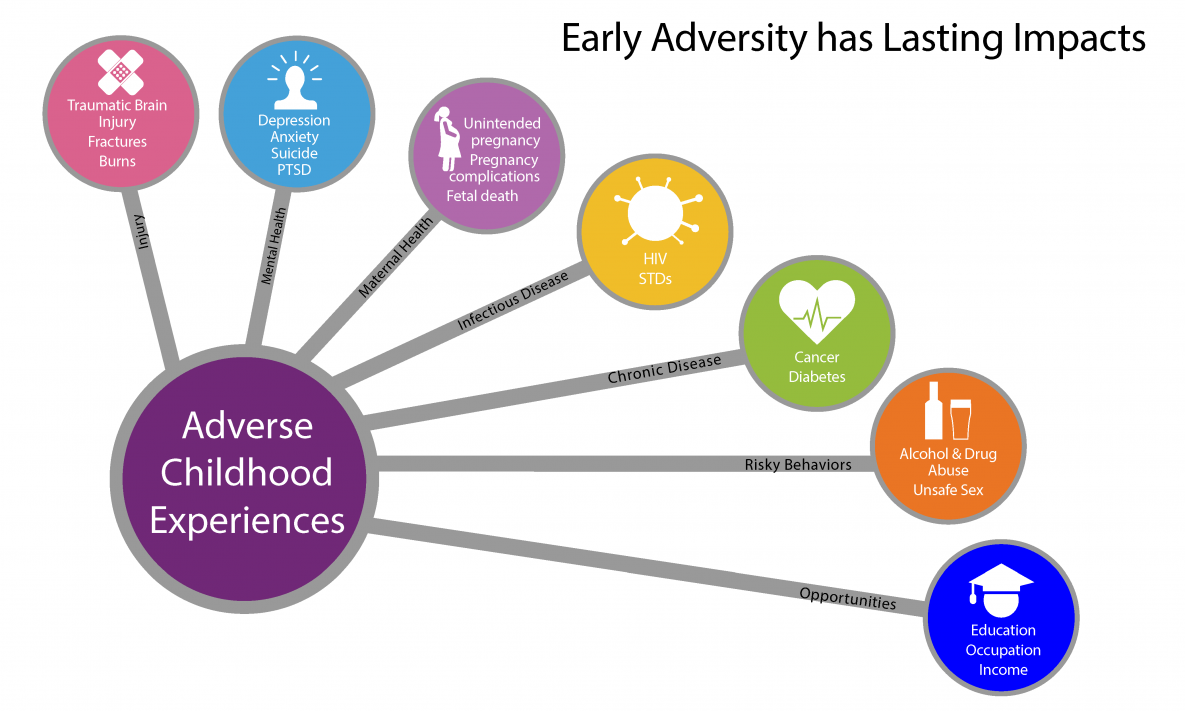

The above is consistent with findings that verbal abuse (yelling, swearing, blaming, insulting) and witnessing family violence can cause higher levels of depression, anger, hostility and dissociation than familial sexual abuse without verbal abuse and domestic violence (Teicher et al., 2006). Parental arguing can lead to hyper-arousal in the infant, causing sleep disturbances and the inability of self-regulation that lead to the development of aggressive or submissive behaviours. In addition, Nocentini et al. (2019), in a meta-analysis, found that conflict, violence, child maltreatment, and authoritarian parenting are associated with an increased risk of bullying and cyberbullying. Check some of the lasting health issues from relationship violence from the ACE Study below. Early adversity may lead to injury (traumatic brain injury, fractures and burns), mental health challenges (depression, anxiety, suicide, PTSD), maternal health challenges (unintended pregnancies, pregnancy complications, fetal death), infectious disease (HIV, STDS), chronic disease (cancer, diabetes), risky behaviours (alcohol & drug abuse, unsafe sex) and decreased opportunities (education, occupation and income).

Figure 16.3 – Impact of Early Adversity

(CDC, 2020)

Resilience Factors

Systematic reviews have been conducted to understand what can help children not develop adverse effects. The resilience factors identified are:

- Secure relationship and emotion regulation (Mueller & Tronick, 2019; Gartland et al., 2019)

- Social support (Racine et al., 2018; Nocentini et al., 2019)

- Warm and affectionate relationship (Nocentini et al., 2019)

- Cognitive skills and academic achievement (Gartland et al., 2019)

Prevention

Primary prevention at a broad policy level is required because the resources required to deal with relationship violence are in the billions. Recommendations of a report prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016, p.10) discusses a public health approach to relationship violence. You can find the chart from the report in figure 16.4. It states five goals and some strategies to prevent violence in families. Primary prevention should be aimed to: 1. Strengthen economic supports to families through improving household financial security and family-friendly workplace policies. 2. Change social norms to support parents and positive parenting through public campaigns and legislation that reduces corporal punishment. 3. Provide quality care and early education through preschools and family engagement, and improved quality of childcare through licensing and accreditation. 4. Enhance parenting skills to promote healthy child development through early childhood education and parenting skills and family approaches. 5. Intervene to prevent future risk through enhanced primary care, behavioural parent training programs, treatment to decrease the harm of abuse and neglect exposure, and treatment to prevent problem behaviour and later involvement in violence (CDC, 2020).

Figure 16.4 – Primary Prevention (CDC, 2020)

The CDC (2019) published a paper on prevention based on the best available evidence for governments and policymakers that expands on the five ideas above.

Actions

These policies need to be translated into actions. In order to develop effective interventions, it may be prudent to understand the perspective of survivors of childhood abuse. Arai et al. (2019) synthesized 33 qualitative reports and “…recommend that professionals be mindful of diversity in children’s experiences of DVA (domestic violence and abuse) and tailor their treatment approach accordingly. Listening carefully to children’s own accounts may be more effective than the assumption that children are affected by DVA in the same way” (p. 10). This is extremely important because many studies report results in averages that may not apply to any single person. Children and young people should be allowed to describe their experience and may require the assistance of professionals to explore these experiences. This process is necessary in order for professionals to respond appropriately. There may be a tool that can be used to help assess children. Ravi and Toni (2019) conducted a systematic review to identify the usefulness of the Child Exposure to Domestic Violence Scale (CEDV). They found the scale had internal consistency and validity (measured what it is designed to measure) even when used across different cultures. They state this tool may be used by social workers.

Although the impacts of relationship violence on a large scale are fairly well understood, there is less research on effective programs. A few systematic reviews are below.

Leijten et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review using qualitative comparative analysis. They found the two components of effective programs were alternative punishment strategies and parental self‐management strategies. The Child Welfare Information Gateway in the United States (2019), in their brief issue state relevant and effective programs, should include the components below. Read the full brief.

-

-

- Providing parents with an opportunity to network with, and receive support from, parents who are in or who have been in similar circumstances

- Efforts to engage fathers

- Treating parents as equal partners when determining which services would be most beneficial for them and their children

- Tailoring programs to the specific needs of families

- Addressing trauma to ensure that it does not interfere with parenting and healthy development

- Ensuring families with multiple needs receive coordinated services

- Offering programs that are culturally relevant to meet the needs among the diverse population

-

In addition requirements of programs include:

-

-

- Positive parent-child interaction and communication skills

- Importance of parental consistency

- Time for parents to practise new skills during coached training sessions

- The use of a time-out when emotions or behaviours escalate

- Requiring providers to have a minimum of a postsecondary/bachelor’s degree and often a graduate degree

- Duration of training or treatment ranges from 5 to 20 weeks

- Services are typically offered in both the home and in the community

- Feedback is provided during parenting sessions (Barth & Liggett-Creel, 2014)

-

The report reviews the literature and has a directory of websites (p. 7) where you can find the evidence for programs. Using all available data, the CDC created positive parenting tips from 0-17 organized by age (CDC, 2020):

One effective service located in Surrey BC is Sophie’s Place Child & Youth Advocacy Centre. It has integrated services that address the needs of children 0-18 years of age who have been sexually, physically or mentally abused. The centre has the ability to video record testimony to decrease the number of times the story has to be repeated.

Effective Research-based Programs

The following are effective research-based programs. Many are offered free of cost. Visit their websites for more information.

Table 16.1 – List of Programs in Canada

| Agency | Program | Summary |

| Healthy Families BC | BC Healthy Connections Project | The BC Healthy Connections Project ensures that all pregnant and parenting women receive the care that they and their families need (Healthy Families British Columbia, 2015). |

| Child and Youth Advocacy Centres (CYAC) | CYAS | CYACs provide coordination (and sometimes co-location) of police, child protection workers and victim services, to minimize system-induced trauma by providing a single, child-friendly setting for victims, witnesses and their non-offending family members. They support children to navigate complex investigation processes, while reducing the number of meetings/interviews and coordinating effective referrals to services such as health and mental health. There a are a number of them across BC. Find one near you |

| Violence is Preventable (VIP) | VIP |

|

| McMaster University | Nurse-Family Program | Home visits provided by nurses and training staff to provide support to mothers (McMaster University, 2015). |

| NSPCC and Fraser Health Authority | Caring Dads | It targets fathers to enhance the safety and well-being of their children (NSPCC, 2017). |

| Strengthening Families Initiative | Strengthening Families Program | It intends to facilitate a closer connection with families allowing parents to get help more easily with staff members (Center for the Study of Social Policy, 2013). |

| PREVNet | PREVNet | It is a national organization, PREVNet that brings together researchers and community organizations from across Canada to address bullying. It is a healthy relationship hub. PREVNet has many resources including toolkits for bullying prevention in schools. It is an excellent site. |

| Stroh Health and BC | Respectful Futures | It is a resource for 12 to 18 year olds that can be delivered in schools and in communities throughout BC in order to prevent relationship violence. Its focus would be to promote social inclusion and to help to create and reinforce a better understanding of healthy and respectful relationships. |

| Group of Organizations | Early Childhood Exposure to Domestic Violence: You can help | It brings resources on the definition of domestic and how it impacts children. This resource also shows signs used to identify violence and strategies to help victims. |

| KPU and Surrey Schools | Peer Mentor Manual for Middle and High School. | Offers peer training manual on healthy relationships for grades 5 and up NEVR, n.d.). |

Table 16.2 – Programs outside Canada

| Agency | Program | Summary |

| Triple P International and the University of Queensland | Triple P Positive Parenting Program | For parents and caregivers of children ages 0–16. It intents to inform parents and caregivers about strategies for promoting social competence and self-regulation in children. It is delivered through Community agency, outpatient clinic, school, adoptive home, birth-family home, foster or kinship home, hospital, or residential |

| National Selfcare Training and Research Center | SafeCare | It provides parent assessment to understand the characteristics and challenges in the family. Second, staff members help parents to use positive connections with their children coaching positive verbal and physical interactions. |

| PCIT International | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy | The main idea in this initiative is to instruct parents to learn a more positive parental style that can help children between ages 2 and 7 manage their behaviour. |

| Center for Growth and Development | Nurturing Fathers Program | Focus on fathers and families at risk of experiencing moderate levels of dysfunction. It teaches parenting and nurturing skills to men through the promotion of healthy family relationships and knowledge of child development. It is delivered through the State or local community agency, school, church, prison, etc. |

| Incredible Years Inc | Incredible Years | Programs for parents or caregivers of children from birth through 12 years old, teachers of young children. To promote social and emotional competence and prevent, reduce, or treat behavioural and emotional problems in young children. Delivered through a community agency, outpatient clinic, school, birth-family home, foster or kinship home, hospital, or workplace. |

| The California Evidence-based Clearing House | Strong Communities Initiative | It Involves the whole community through voluntary assistance by neighbours for one another, especially for families of young children. |

| Duke Sanford Center for Child & Family Policy | The Durham Family Initiative | It provides resources like therapeutic and respite care, family education, and home-based services to high-risk families (Duke Sanford – Center for Child and Family Policy, n.d.). |

| HRSA Maternal & Child Health | The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program | Home visits are provided to pregnant women and families in order to assess and provide resources. |

| United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC | University Module Series Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice | Series of Modules for University Students, Module 12 Violence against Children |

References

Barth, R. P., & Liggett-Creel, K. (2014). Common components of parenting programs for children birth to eight years of age involved with child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, 40, 6-12.

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm and programmatic activities. https://www.governor.wa.gov/sites/default/files/documents/BRCCF_20160614_ReadingMaterials_can-prevention-technical-package.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the best available evidence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/preventingACES-508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Positive parenting tips. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/infants.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC-Kaiser ACE study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html

Center for the Study of Social Policy. (2013). Strengthening families: increasing positive outcomes for children and families. https://cssp.org/our-work/project/strengthening-families

Children’s Bureau. (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. U.S. department of health & human services, administration for children and families, administration on children, youth and families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

Duke Sanford – Center for Child and Family Policy. (n.d.). The Durham family initiative https://childandfamilypolicy.duke.edu/project/durham-family-initiative/

Gartland, D., Riggs, E., Muyeen, S., Giallo, R., Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H., Herrman, H., Bulford, E., & Brown, S. J. (2019). What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(4), e024870. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024870

Healthy Families British Columbia. (2015). BC healthy connections project. https://www.healthyfamiliesbc.ca/home/bc-healthy-connections-project

Leijten, P., Gardner, F., Melendez-Torres, G. J., van Aar, J., Hutchings, J., Schulz, S., Knerr, W., & Overbeek, G. (2019). Meta-analyses: Key parenting program components for disruptive child behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(2), 180-190. https://jaacap.org/article/S0890-8567(18)31980-4/fulltext

Learning to End Abuse. (2017, October 11). Impact of domestic violence on children. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUB9tpv_u9k&list=PLooxoqkxjFkJdTSLDwldYZWsVf5DbevGi&index=5

McMaster University. (2015). Nurse-Family program. https://nfp.mcmaster.ca/

Ministry of Children and Family Development. (2017). The B. C. Handbook for action on child abuse and neglect. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/public-safety-and-emergency-services/public-safety/protecting-children/childabusepreventionhandbook_serviceprovider.pdf

Mueller, I., & Tronick, E. (2019). Early-life exposure to violence: Developmental consequences on brain and behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 156.

Network to Eliminate Violence in Relationships. (n.d.). Peer to peer manual: Healthy relationships, sexual health, drug abuse, and internet safety – a peer mentoring guide. https://www.kpu.ca/sites/default/files/NEVR/Peer%20Mentor%20Manual%20for%20Middle%20and%20High%20Schools.pdf

NSPCC. (2017). Caring dads program. https://www.caringdads.org/about-caring-dads-1

Nocentini, A., Fiorentini, G., Di Paola, L., & Menesini, E. (2019). Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 41-50.

Nurse-Family Partnership (n.d.). Helping first-time parents succeed. https://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. (2015). http://www.pcit.org/

Petersen, AC, Joseph, J, & Feit, M. (2014) New directions in child abuse and neglect research. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK195987/

Racine, N. M., Madigan, S. L., Plamondon, A.R., McDonald, S.W., & Tough, S.C. (2018). Differential associations of adverse childhood experience on maternal health. Am J Prev Med, 54(3):368‐375. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.028

Ravi, K.E., & Tonui, B.C. (2020). A systematic review of the child exposure to domestic violence scale. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(1), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz028

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When intimate partner violence meets same-sex couples: A review of same-sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506

Statistics Canada. (2015). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/170216/dq170216b-eng.pdf?st=JuEgB_N3

South Asian Institute. (2019). Developing strategies on violence prevention and

community safety in Abbotsford, BC. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/33/2019/10/Dandurand-McCormick-Bains_2019_Violence-prevention_SASI-SARF-REPORT.pdf

Strengthening Families Initiative. (n.d.). Strengthening Families program. https://strengtheningfamiliesprogram.org/

Strong Communities Initiative. (n.d.). Strong Communities for Children program. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/strong-communities-for-children/detailed

Teicher, M.H., Tomoda, A., & Andersen, S.L. (2006). Neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1071, 313–323.

The Child Development Centre. (2020). Sophie’s Place Child and Youth Advocacy Centre. https://the-centre.org/sophies-place/

The Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). Parent Education to Strengthen Families and Prevent Child Maltreatment. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/parented.pdf#page=2&view=What%20the%20research%20shows

Triple-P Initiative. (n.d.). Triple-P in a nutshell. https://www.triplep.net/glo-en/find-out-about-triple-p/triple-p-in-a-nutshell/

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC. (2019). The Doha Declaration: Promoting a culture of lawfulness. https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/crime-prevention-criminal-justice/module-12/index.html

World Health Organization. (2016). Child Maltreatment. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment