8. Sociological Theories of Crime

8.2 The Chicago School

Dr. Sean Ashley

The Chicago School

In the late 1800s, few cities in North America were as diverse as Chicago. The population of the city was rapidly expanding thanks to successive waves of immigration from Europe. In 1870, the city had a population of 299,000, which grew to 1,698,600 by 1900, making it the fastest growing city in the world at the time (Cumbler, 2005). The city provided a tableau for a new way of thinking about crime and society that came to be known as the Chicago School.

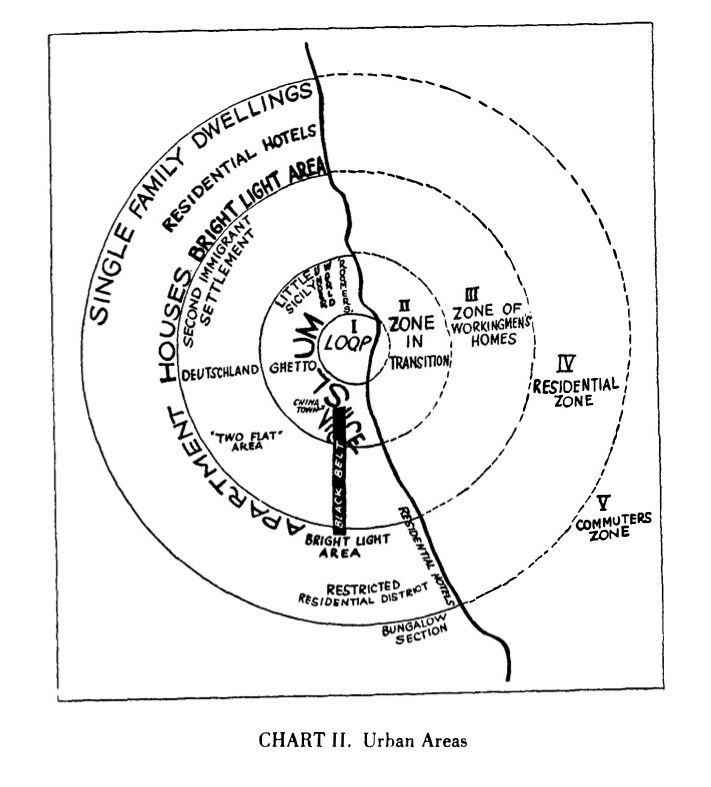

The Chicago School had a distinctly macro-level ecological approach to studying crime. Under the influence of Robert Park and Ernest Burgess, generations of researchers were trained to go out into the city and learn about the dynamics of delinquency firsthand. In their book The City, Park et al. (1925/1967) observed that crime was not evenly distributed throughout Chicago but was concentrated in particular neighbourhoods. The model they proposed for understanding the geographic distribution of crime was akin to the rings on a tree, with each concentric circle representing a different urban zone. Certain zones were marked by greater degrees of social disorganisation due to the transitional nature of these areas as new immigrant communities moved in and older ones moved out. Crime was a characteristic of this transitional state, and while unwanted it represents the normal dynamic of a developing city, with disorganisation leading to reorganisation over time (Park et al., 1925/1967).

Working in this tradition, Frederic Thrasher’s (1936/2013) book The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago catalogues the activities of gangs operating in the city during this period. Like Park and Burgess, Thrasher argues that gangs are located in interstitial areas of the city, the zones between the settled, more organised neighbourhoods.

The characteristic habitat of Chicago’s numerous gangs is the broad twilight zone of railroads and factories, of deteriorating neighbourhoods and shifting populations, that borders the city’s central business district on the north, west, and south. The gangs dwell among the shadows of the slums in this zone (Thrasher, 1936/2013, p. 3).

Perhaps the most famous example of the ecological perspective on crime to emerge from this period is Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay’s (1942) book Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Shaw and McKay (1942) argue that the key variable that leads to crime is the social disorganisation that characterises interstitial areas. They found that zones of transition are characterised by higher levels of residential mobility, ethnic heterogeneity, and lower socio-economic status (Sampson & Groves, 1989). Drawing upon decades of court records, they show that it does not matter which ethnic group lives in the area—it is the zone itself that is criminogenic. As groups move to other zones, their crime rates correspondingly drop (Lilly et al., 2019). While their work builds on the ecological approach, Shaw also pioneered the use of life histories within criminology, such as his semi-autobiographical account of the life of a juvenile delinquent in The Jack-Roller (Shaw, 1966).

The approach taken by the Chicago School remains influential today, but there are nevertheless some important limitations to their findings. While the concentric zone model may have worked for Chicago, it is not characteristic of all cities. The idea of disorganisation itself has also been criticised; while such neighbourhoods may look disorganised to outsiders, for those who live within them there is a definite order made up of informal associations and networks (Cohen, 1955). Despite these criticisms, Sampson and Groves (1989) provide empirical support for Shaw and McKay’s approach by measuring the relative degrees of social disorganisation within neighbourhoods and showing some correlation with respective crime rates.

Media Attributions

- Concentric Zones © Park, R., Burgess, E. & McKenzie, R. The city. University of Chicago Press, 1967 p. 55 is licensed under a Public Domain license

Studying crime in terms of its environmental influences.

An approach that links crime and delinquency to the disordered ecological characteristics of a neighbourhood.

In between spaces