7. Psychological Theories of Crime

7.8 Integrative Models of Criminality

Dr. Jennifer Mervyn and Stacy Ashton, M.A.

Theories under the umbrellas of individual psychology emphasise personality, cognitive fallacies, psychopathology, and brain structure. Evolutionary psychology looks at ancient survival pressures and their impact on the human genome. Cultural psychology looks at how individual behaviour is constructed by society. Biopsychosocial criminology, on the other hand, is a multidisciplinary perspective that views criminal behaviour by considering the interactions between biological, psychological, and sociological factors. This section describes three models that integrate theories from individual, evolutionary, and cultural approaches in their application to criminal behaviour.

- Moffitt’s Developmental Taxonomy: explains the development of antisocial behaviour as affected by biology, socialisation, and stages of development.

- General Aggression Model: explains the biological, personality, cognitive and social learning factors influencing an aggressive act.

- Risk Needs Responsivity Model: provides a method for offender assessment and treatment by examining the needs underlying criminal behaviour.

- Trauma-informed Systems of Care: combines the neurobiology of trauma with an analysis of the trauma-inducing aspects of the criminal justice system.

Developmental Taxonomy

The developmental taxonomy (Moffit, 1993, 2018) describes two types of offenders differentiated by their biology, parenting, personality, and socialisation: life-course-persistent offenders and adolescent-limited offenders. Life-course-persistent offenders are rare and have externalising behaviour from an early age continuing into adulthood. Neurological differences causing impulsivity and reactivity are believed to underlie their behavioural problems. Without intervention, difficulties with peers and school result, snowballing into later problems such as early school leaving and criminal activity. Early social rejection from peers is a major risk factor for later antisocial behaviour (Cowan & Cowan, 2004), and these individuals often eventually associate together (Laird et al., 2009). The individuals following this life-course trajectory are considered the smallest group of offenders, but they are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime (Piquero et al., 2012).

Conversely, adolescent-limited offenders engage in minor antisocial behaviour during a developmentally normative stage in the teenage years but have an otherwise normal early childhood. Adolescent-limited offenders determine the benefits of a criminal lifestyle are not worth the risk, and they change in their early adulthood. According to the developmental taxonomy, these individuals are capable of easily changing because they have well-developed social and educational skills.

General Aggression Model

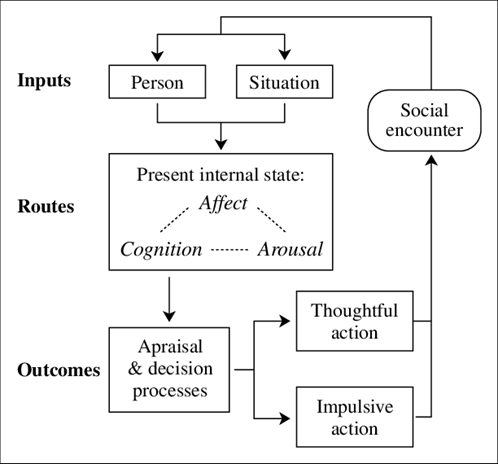

The general aggression model (GAM; DeWall et al., 2011) explains how various factors, including biology, personality, cognition and social learning, work together to produce an aggressive incident. The GAM is structured in terms of responses to a situation: there are inputs (aspects of the person and situation) and outputs (results from decision-making that was either thoughtful or impulsive). Impulsive actions are more likely to be violent than thoughtful actions. Once violence is used by a person, the theory suggests that violence becomes a tactic more likely to be used again in the future, forming a behavioural pattern. Whether violence happens or does not happen in response to a situation depends on how the individual involved perceives and interprets the social interaction, their expectations of various outcomes, and their beliefs about the best ways to respond.

Ferguson and Dyck (2012) outline some assumptions made in the GAM, including the assumption that aggression is primarily learned. Ferguson and Dyck (2012) suggest that other factors, such as environmental stress, play a more important role in instigating aggression. In addition, they note that the GAM seems to explain hostile, reactive aggression without adequately explaining aggression that is calculated, goal-directed and given forethought.

Risk Needs Responsivity Model

Two Canadian researchers, Don Andrews and James Bonta (2017), developed the risk needs responsivity (RNR) model for the assessment and treatment of offenders after many decades of researching the factors most related to criminal and violent behaviour. Their model incorporates social learning, cognition, personality, and social factors. The RNR model has three main parts. First is the “risk” principle, which involves assessing offenders on the eight risk factors research indicates are most directly linked with criminal behaviour. The intensity of treatment should match the level of risk, with individuals that score higher receiving more rehabilitation efforts. Criminogenic risk factors are outlined in Table 7.9.

| History of criminal behaviour | How early crime starts, frequency and variability of criminal behaviour |

|---|---|

| Antisocial personality pattern | Having traits such as impulsivity, sensation-seeking, hostility and callousness |

| Antisocial associates | Having friends that are involved in crime |

| Antisocial attitudes | Having cognitions that rationalize antisocial behaviour and/or disdain towards the law and justice system |

| Substance abuse: | Misuse of alcohol and drugs |

| Family/marital issues | For youth offenders, parents provide little warmth or control. For adult offenders, family/intimate relationships are unsupportive and/or with antisocial others |

| Leisure | Few prosocial leisure activities |

| Work/education | Poor performance and/or low satisfaction with work and/or school. |

Second, the “need” principle states that treatment should focus on addressing the needs associated with each risk factor found for the offender; factors the offender scores low on can be set aside in favour of rehabilitation focused on reducing the risk factors they score high on. Criminogenic needs are defined in response to eight risk factors; offenders scoring high on the work/education risk factor would be enrolled in alternative education or job retraining, while offenders scoring high in the antisocial attitudes risk factor would be referred to individual and/or group therapy.

Third, the “responsivity” principle states that treatment should be provided in a way that optimises the offender’s successful response to the treatment. Treatment should be evidence-based but also implemented in a way that considers the individual’s learning style, motivation needs and other characteristics that might impact treatment success.

The RNR approach has been criticised for being demotivating (Ward, 2002). Instead of RNR’s focus on risks, what is wrong, and what needs fixing, the good lives model (Ward & Gannon, 2006) suggests that a positive approach that addresses a person’s strengths, priorities, and ways to better their lives may be more effective. The good lives model assumes that all human beings are motivated by the same “primary goods,” such as relatedness, agency and creativity. Offenders are attempting to attain these primary goods using inappropriate means and require new ways to obtain the primary goods they seek. The good lives model and RNR model focus on individual assessment and rehabilitation based on criminogenic needs and offender motivation, but the good lives model focuses on the offender’s goals instead of their deficits.

Models that rely on risk assessment use tools that have not been shown to be valid across cultures. Recently, a Canadian Indigenous offender successfully challenged the use of risk assessment tools in the Supreme Court of Canada, targeting the fairness and validity of making decisions about Indigenous offenders’ risk based on these tools (Ewert v. Canada, 2018). The failure to recognise biases in risk assessment adds to obstacles and overrepresentation already faced by Indigenous offenders in Canada (Forth & Book, 2017; Hart, 2016; Perley-Robertson et al., 2019; Wilson & Gutierrez, 2014). Rather than relying on risk factors that could unintentionally criminalise characteristics common to disadvantaged areas, such as low educational attainment, antisocial peers and criminal history, Indigenous leaders suggest strength-based approaches rooted in culturally relevant social norms (Shepherd & Anthony, 2018).

Trauma-Informed Systems of Care

A trauma-informed approach draws on the interplay of neurobiology and adverse childhood experiences to explain the development of criminal behaviour and offers approaches to law enforcement, mental health treatment, and rehabilitation that seek to avoid re-traumatisation. Existing systems of care inadvertently contribute to the creation of toxic environments that interfere with mental health recovery and criminal rehabilitation. In the process, these systems undermine the well-being of police and mental health workers so that their own experiences of trauma on the job reduce their ability to effectively address criminal behaviour.

Staff who work within a trauma-informed environment are taught to recognise how organisational practices may trigger painful memories and re-traumatise clients with trauma histories. For example, they recognise that using restraints on a person who has been sexually abused or placing a child who has been neglected and abandoned in a seclusion room may be re-traumatising and interfere with healing and recovery.

A trauma-informed approach reflects adherence to six key principles rather than a prescribed set of practices or procedures. These principles, which are outlined in Table 7.10, may be generalisable across multiple types of settings, though their terminology and application may be setting- or sector-specific.

| Safety | Staff and the people they serve, whether children or adults, feel physically and psychologically safe. |

|---|---|

| Trustworthiness and Transparency | Organizational operations and decisions are conducted with transparency with the goal of building and maintaining trust with clients and family members, among staff, and others involved in the organization. |

| Peer Support | Peer support and mutual self-help are key vehicles for establishing safety and hope, building trust, enhancing collaboration, and utilizing personal stories and lived experience to promote recovery and healing. |

| Collaboration and Mutuality | Importance is placed on leveling of power differences between staff and clients and among organizational staff, from clerical and housekeeping personnel to professional staff to administrators, promoting meaningful sharing of power and decision-making. |

| Empowerment, Voice and Choice | Throughout the organization and among the clients served, individuals’ strengths and experiences are recognized and built upon. The organization fosters a belief in the primacy of the people served, in resilience, and in the ability of individuals, organizations, and communities to heal and promote recovery from trauma. Staff facilitate recovery instead of controlling recovery. |

| Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues | The organization actively moves past cultural stereotypes and biases (e.g., based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, religion, gender- identity, geography, etc.); offers access to gender responsive services; leverages the healing value of traditional cultural connections; incorporates policies, protocols, and processes that are responsive to the racial, ethnic and cultural needs of individuals served; and recognizes and addresses historical trauma. |

Trauma-informed care recognises the impact of historic events on current-day practices. The Truth and Reconciliation movement has brought new and needed attention to the multi-generational effects of colonialism on the Indigenous peoples of Canada, which have led to many devastating impacts including substance abuse and domestic violence (Monchalin, 2016). Preliminary research indicates that incorporating culturally relevant programming for Indigenous offenders leads to higher completion rates and more effective treatment outcomes, including lower odds of recidivism (Gutierrez et al., 2018). Importantly, creating programs that are culturally relevant requires consulting and collaborating with Indigenous peoples and recognising the diversity and needs within their communities.

a multidisciplinary approach that seeks to understand criminal behaviour by examining the interactions between biological, psychological and sociological factors.