5. Methods and Counting Crime

5.2 Planning

Dr. Wendelin Hume and Ashly Hanna, B.A.

As part of the planning process, the research often starts with a topic and then a research question begins to form. As a researcher, what is a social question you would like the answer to or what is a social problem you would like to find possible solutions for? The research question specifies the variables to be studied and their relationship to each other. A variable is a person, place, thing, or phenomenon you are trying to measure in some way, and it varies (Bachman & Schutt, 2017). For example, age is a variable, as is income and socioeconomic status. A hypothesis is your informed thought or expectation of what the relationship is between variables, and it is often written as an “if, then” statement (Hagan, 2014). For example, one might hypothesise that “If the employment rate is low, then the property crime rate is high.” The hypothesis should clearly indicate the directionality of each variable, in this case, the employment rate and property crime (as one increases, the other decreases, or vice versa, or perhaps they both change in the same direction) as well as the temporal ordering of variables (low employment comes before high property crime). This “if, then” characteristic points to an essential element of a hypothesis: that it be testable.

Beginning in the early planning stages, it is important for researchers to begin to understand and value Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies and to have an understanding of the basic scientific model. This blending of Indigenous worldviews and Western science is often referred to as Two-Eyed Seeing (Peltier, 2018). Cooperation between the researcher and the researched may lead to improvements in research methods and findings. One important step in this cooperative process is understanding first what the communities to be researched already know and have. This culturally relevant information can improve understanding between the researcher and the subjects, and it can provide a good context for research in these early planning stages. Collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders and communities to co-design the study, co-frame the research questions, co-interpret results, and jointly co-create solutions is a much-needed improvement. Of course, for the research project to truly be joint, any grant or other funding obtained for the research should be shared. Research decisions and titles such as principal investigator, lead investigator or co-investigator as well as authorship on publication efforts and credit for work completed should also be shared.

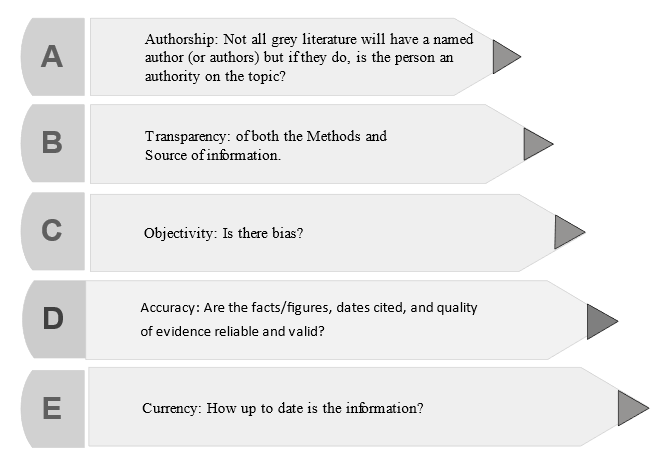

While forming our research question, we want to begin to examine existing literature about studies that have already been done on our topics. In addition to exploring the usual books and journal articles, we should work to avoid academic imperialism, or only learning from big name authors in mainstream journals, by including grey literature in our preliminary research efforts. Grey literature is literature or evidence that is relevant to the research question but not published in typical commercial or academic peer-reviewed publications (See GreyNet International). Grey literature can include government and community reports, conference papers, dissertations, and other sources. Incorporating grey literature reduces publication bias and increases the comprehensiveness of any systematic literature review.

The researcher will need to evaluate the information as there may not have been a peer review process.

Let us turn to our two examples now and discuss how we might begin the planning for each. Using the cultural insights from the Indigenous community as well as the understanding from our initial review of the literature for our examples, we might start by stating that we want to examine financial exploitation by asking a set of closed-ended survey questions that have been used successfully in other financial exploitation research; this would be a deductive, quantitative approach to this research. We start to think about how we might later word the questions so they are culturally relevant, such as asking about “gifting” rather than “donations” and if money has been “missing” rather than “stolen” or “swindled.”

With our spirituality example, perhaps nothing appears in the typical literature, but we know that Indigenous cultures, and by extension Indigenous research, recognises spirituality as an important contribution to ways of knowing. Western research ignores spirituality, which can cause tensions between research and its application in certain communities. For instance, perhaps elders told us during our meetings with them that the last group of researchers who studied the tribal people had concluded that Indigenous peoples were lazy and not concerned about their health because they did not use the gym that was built for them. What the researchers did not realise was that the facility was built on sacred ground and the local people chose not to use it unless it was moved to a non-sacred space. Based on this informal but very important initial input from elders, we decide that what we should do is ask broad, open-ended questions about spirituality, whether elders are assisted in practising their spirituality or if anything is keeping them from practising their spirituality. This is an inductive, qualitative approach to the study on spirituality; the approach emerged from the open-ended and open-minded line of questioning at the outset, which will be explained in more detail below in the section on choice of method.

a person, place, thing or phenomenon that you are trying to measure and that varies in value. Age, income, and number of crimes committed are all examples of variables.

a proposed explanation used as a starting point in the deductive model for further investigation, or emerging at the end of the research process in the inductive model. A hypothesis is typically written as an “if, then” statement and outlines how we expect the variables to be related to one another and the direction of that relationship.

the blending of Indigenous world views and Western science.

an unequal relation between academics where one group dominates while other groups are ignored or silenced.

information produced outside of traditional publishing and distribution channels, including government and community reports, conference papers, and dissertations.