5. Methods and Counting Crime

5.1 The Research Process

Dr. Wendelin Hume and Ashly Hanna, B.A.

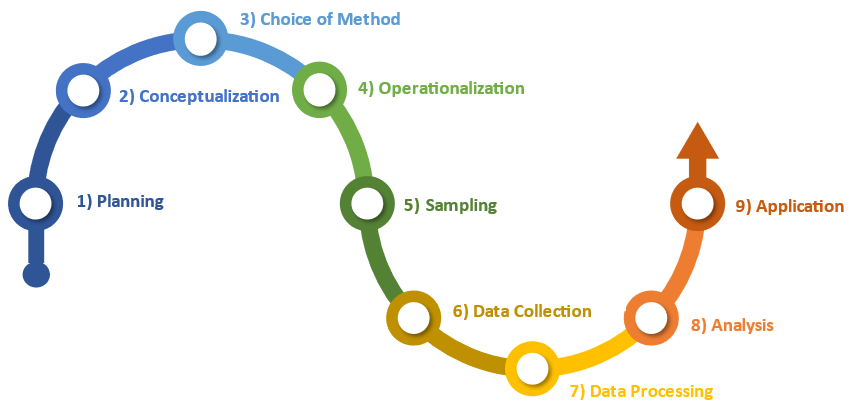

An understanding of quality research methods is fundamental to informed citizenship, scientific advancement, economic activity and government decision-making. While research designs vary depending on a number of factors such as the topic being studied, the variables under consideration and the preferences and training of who is conducting the research, a basic Western research design is a good place to start in discussing research methods. In the subsections below, and as shown in Figure 5.1, each of the nine steps of this basic research process are outlined, beginning with planning.

Planning

A key part of the planning stage is knowing what your objectives are. Are you trying to discover new information, or are you trying to find an answer to influence policy and programs? As you start to plan, you start to take a look at other studies on the topic. You look at the theory (or theories) referred to in those studies and the hypothesis they may have set out to test. You start to think about what your own research question(s) might be.

Conceptualization

As you envision and start to become clearer on the key question(s) for your own research project, you are engaging in conceptualisation and creating a mental picture of what your research methods will look like and what the concepts of interest are. You are very specific about what these concepts mean in your project. For example, if you want to study the fear of crime, what exactly do you mean by fear and what kind of crime are you referring to? Are you interested in whether people are afraid to walk alone at night, or are you interested in whether they are afraid that their identity will be stolen? You continue to review existing literature. This can help shape your image of your research project and identify what gaps exist in the literature, which you may choose to address in your own project.

Choice of Method

As you think about what you are studying, you need to choose a particular method that is suited to answer your research question. For instance, determining someone’s opinion about something might best be captured by using a survey, whereas learning about actual behaviours may best be documented through observations in field research. Looking at what methods were used in other studies on the same or a similar topic may be helpful here.

Operationalization

Now that you have identified the concepts and chosen the most appropriate method to answer your research question, you must determine specifically how you will measure the concepts. This is called operationalisation. For instance, in a survey, what specific wording for the questions and options for answers will accurately capture the concepts of interest? If you are doing field research, what specific observations will you be making?

Sampling

Next, you need to consider who you are studying. You need to think about the overall population you want to draw conclusions about and then choose an appropriate sampling technique because that population is typically too large to study each and every member. Furthermore, if you are dealing with people instead of an official dataset, it may be difficult to obtain permission from everyone. The sample you end up with will be a subset of those data or people from the larger population.

Data Collection

Next, you need to collect your data via whatever methods you have chosen. Data collection may happen quickly if, for instance, you had a short survey you administered to a small number of people. However, the collection process may instead take place over a long period of time, such as observing changes in inmates over a three-year study in a prison setting.

Data Processing

Depending on the method chosen, you now have a number of questionnaires with responses or perhaps notebooks full of recorded observations. These raw data will need to be processed into a useable form. While a fulsome discussion of the various levels of measurement is outside of the scope of an Introduction to Criminology textbook (typically this is covered in an introductory research methods course), it is important to understand at this stage that data (whether they are textual or numerical) are typically processed using either Excel or a statistical analysis program, such as SAS or SPSS, or if textual, a qualitative software program like Nvivo. The process involves extracting bits of data from the instrument used (such as the survey or the interview notes) and organising them in such a way that allows for easy analysis.

Analysis

Once the data are processed, they must be analysed. Analysis can be statistical in a quantitative project or thematic in a qualitative project. Either way, the goal of analysis is to make sense of the data and to synthesise and summarise the findings in a way that can be communicated to a larger audience. Graphs, tables, and charts are typically used to visually present data that have been analysed. In this stage, we often refer to the literature again to connect what we have found in our own research to the existing body of knowledge.

Application

The final stage of this research process is application, which involves using the conclusions you have reached to inform or educate others. At times, research can be used to influence policy making and may result in improvements such as fewer victimisations, fewer traffic accidents, and so on. As a final step, the researcher should also consider what errors may have been made that could be corrected in future research and, just as importantly, what future research would be helpful moving forward. This would be a valuable contribution to the literature and help other researchers identify gaps and choose their own research topics to explore.

9 Steps of the Research Process: A Brief Illustration

Perhaps I notice there are few victim services programs for First Nation elders in my community. When I ask program administrators why there are not more programs, they explain that there are low rates of abuse of the elderly so programs are not needed. I start

- planning what my research question might be and think about how I could research to determine if this assumption about low victimization rates is correct. I would start looking at other studies on the topic as well.

- I then need to conceptualize the overarching research question more concretely and think about what method I could use to collect useful data about the elderly and their needs. I will continue to look more in depth at other studies on the same or similar topics.

- As I choose a method, I will continue to examine related existing research on this topic and see what methods they used, and I may consult with a few elders to receive their input and advice. I may choose to have tribal service providers give a survey to the elders in their community.

- Then, I operationalize the specific (survey/interview) questions to be asked by making sure they are culturally relevant, respectful and worded in such a way that they can uncover if there is abuse taking place but perhaps not being reported to officials. Since the service providers are quite busy, I would not expect them to give a survey to every elder, but perhaps we could

- obtain a random sample of 70 elders out of the population of 210 elders in the community. I provide the survey in a readable format where elders can fill in the bubble sheet or circle their answers to the questions and give it back to the service providers, thus completing the

- data collection. While showing concern for the participants is not a specific step, it should always be a part of the overall research design. Once the questionnaires are returned, I will use a coding sheet to enter the responses into my statistical program in numerical form appropriate for

- data processing. Once all the data are entered and double checked, I will

- run analyses describing things such as the average age of the people who completed the survey and whether or not experiences of abuse were reported. I will compare my findings with the findings of previous research. The service providers will assess whether the questionnaire brought up troubling emotions for the elders or if it encouraged the elders to tell someone about their victimization. Based on my findings, which are shared only with permission of the tribe, I may

- apply the findings by recommending that additional services be provided and that new methods of dealing with offenders be developed. This would involve consultation with elders, so more elders will be willing to report when bad things happen to them or at least so they could seek out available services. I might start thinking about completing a follow-up survey in about two years to see if the situation has improved for elders in the community after programmatic changes take place.

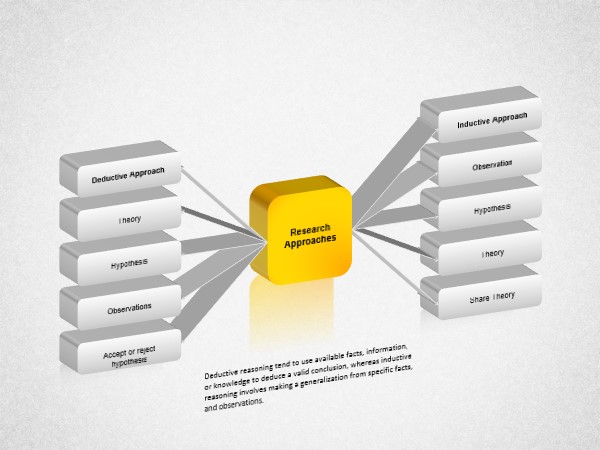

We will now go through the nine steps again, in much more detail using two examples. One example will focus on the possible financial exploitation of Indigenous elders and will employ a deductive, quantitative approach, and the other will explore the concept of spiritual abuse of Indigenous elders using an inductive, qualitative approach. See Table 5.1 below for a summary of key features of the quantitative vs qualitative approaches and Figure 5.2 for a visual graphic of the inductive versus deductive approaches of research.

| Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

|---|---|

| focuses on testing or confirming theories and hypotheses | focuses on exploring ideas and understanding subjective experiences |

| focus on statistical analysis | focus on thematic, textual analysis |

| mainly expressed in numbers, graphs and tables | mainly expressed in words |

| requires many respondents | requires few respondents |

| closed-ended (multiple choice) questions | open-ended questions |

| methods include experiments, surveys | methods include interviews, field observation |

| key terms: testing, measurement, objectivity, replicability | key terms: understanding, context, complexity, subjectivity |

a typically European or colonial approach with adherence to the scientific method grounded in a belief in individualism, autonomy, purposefulness and meaning.

an explanation for observed facts and laws that relate to a particular phenomenon. It is made up of a set of concepts and an explanation of how these concepts are related to one another.

a proposed explanation used as a starting point in the deductive model for further investigation, or emerging at the end of the research process in the inductive model. A hypothesis is typically written as an “if, then” statement and outlines how we expect the variables to be related to one another and the direction of that relationship.

to form a concept or idea about something and to become very specific about what we mean by those concepts for the purpose of our own research.

a method of collecting data by asking respondents questions in a questionnaire.

a qualitative method that involves observing and possibly interacting with research subjects in their natural environment.

turning abstract concepts or phenomena that may not be directly observable into measurable observations. For example, this would involve selecting the exact wording of survey questions.

all members of a particular area or group, or all things, that you want to learn more about from which a sample is drawn.

the process of selecting which people or things to research (i.e. selecting our sample) from the larger population, with the typical goal of generalizing our findings from the sample to the population. In quantitative research, our sampling techniques are random, while in qualitative research, we use non-random sampling techniques to select those people or things with specific characteristics of interest.

data sets often produced by official governmental agencies for administrative purposes, such as Census data or crime figures.

a subset of people or things from the larger population we want to know more about. In quantitative research, our samples are larger than in qualitative research.

data collected directly from the source and that exist at this point without any processing, transformation, or analysis. Interview notes or survey responses are examples of raw data.

the process of compiling and reviewing information, and then summarizing and synthesizing the data, often with the aide of statistical techniques, to reach a conclusion or explanation about the phenomenon under study.

research that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data. It can involve testing causal relationships and making predictions. Methods include closed-ended surveys and experiments.

research that involves the collection and analysis of in-depth textual or verbal, non-numerical data. Methods include interviews, focus groups, and field observation.

a research model that involves working from the general to the specific, or from theory to data collection. The deductive model employs quantitative methods of research.

a research model that involves working from the specific to the general or from observations to the development of theory. The inductive model employs qualitative methods.