14. Victimology

14.6 Impacts of Victimisation

Dr. Jordana K. Norgaard and Dr. Benjamin Roebuck

Trauma is messy. There’s no road map; there’s no structure that’s going to work perfectly for all people, all the time. Getting through it is tough. It takes a lot of resilience, a lot of strength and people in your corner. A support network is so important. — Female survivor of sexual assault (Roebuck et al., 2020a).[1]

Victimisation can affect people physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. When survivors are unable to work or miss work because of the time involved in talking to police, lawyers, or attending court, they can lose their income or housing, and accumulate debt. Some survivors experience permanent disabilities or long-term symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can include dissociation, hyperarousal, avoidance, and feeling trapped in negative thought patterns or moods (Andrews et al., 2003). The impact of victimisation can vary based on the characteristics of the crime, the characteristics of the victim and their relationship to the offender, and post-crime factors like receiving access to timely and effective support (Karmen, 2020; Roebuck & Stewart, 2018; Wemmers, 2017). After victimisation, survivors are suddenly forced to navigate many new and complicated realities, potentially interacting with healthcare providers, media, police, and victim service providers, all while grieving and being presented with complicated choices about how to move forward (Roebuck et al., 2020a). For many survivors, there is so much work to do after experiencing violence that it can take a while before they have the time and space to process what has happened. Throughout this time, friends and family may not know what to say and may be silent to avoid causing further distress or they might offer unhelpful advice (Brison, 2002).

Survivors can be particularly sensitive to language. Consider the impact of the following words:

“They are in a better place now”

“Everything happens for a reason”

“You’re lucky it wasn’t worse”

“I understand what you’re going through”

“You shouldn’t have had so much to drink”

“Do you have closure now?”

“You need to forgive them and move on”

“Triggered” (gun-related violence)

Highlight Box 6: Documentary and Discussion Guide – After Candace: The Art of Healing

Cliff and Wilma Derksen share their story of resilience and posttraumatic change following the murder of their daughter Candace in 1984. Wilma reflects on complex grief and healing, while Cliff shares the power of art to transform trauma. Full of wisdom, faith, and vibrant creativity, Cliff and Wilma help us understand the multifaceted nature of violence and recovery. Filmed on location in Winnipeg, Canada.

Resilience, Posttraumatic Growth, and Posttraumatic Change

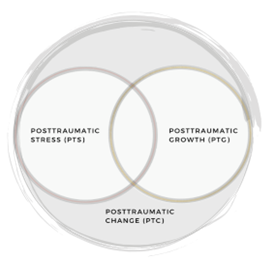

While the pain of victimisation may never fully subside, many survivors find ways to move forward with their lives, navigating and negotiating their way through adversity—this is the process of resilience (Ungar, 2004). Some survivors identify that doing this work also contributes to posttraumatic growth (PTG). Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) found that trauma survivors commonly report growth in five domains: new possibilities, relating to others, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. Growth-related language provides an optimistic framework for some survivors, while others resist the idea of PTG. Posttraumatic change is a broader concept that incorporates posttraumatic stress and PTG responses to violence, but also creates room to consider how survivors experience changes that are hard to frame as negative or positive, or paradoxes such as a survivor feeling proud of their advocacy work and while finding it humiliating at the same time (Roebuck et al., 2022).

Survivor Reactions to Services

“When people ask what the worst thing was to ever happen to me, I don’t say the sexual abuse or rape. I say it was the trial.” – Female survivor of childhood sexual assault (Roebuck et al., 2020a, p. 15).

Some victims choose not to participate in services to avoid re-victimisation. Re-victimisation is the process by which victims feel victimised for a second time by the criminal justice system and legal processes (Ahlin, 2010). Emotionally, victims may not be able to cope with this level of stress and may feel unprepared to initiate contact for services and/or continue seeking services to help them with their recovery. Some victims have been reported to have symptoms of their (PTSD) triggered through court proceedings (Kilpatrick & Acierno, 2003). Findings from a victim satisfaction survey administered by the Canadian Department of Justice found that few victims (approximately 21%) used specialised victim services when provided at no-cost to the victim (Department of Justice Canada, 2005). Patterson et al., (2006) contended that there are several possible explanations for the refusal and/or withdrawal of these services, similar to the reasons for not reporting victimisation to police. A close relationship to the perpetrator, the gender of the victim and/or survivor, and fear can all play a role in service participation. Patterson et al. (2006) found that some victims of crime were more hesitant to share their experiences with victim service providers for fear of having any information used against them in the future. The Canadian Department of Justice (2005) found that victims were less likely to engage in victim-based services when they were less satisfied with the criminal justice system. Survey respondents often felt frustration when information was limited, inaccurate, and/or confusing (Department of Justice Canada, 2005). Dissatisfaction also arose when participants were forced to initiate contact themselves with a criminal justice professional as well as from receiving incorrect/inconsistent information from criminal justice professionals due to changes in staffing (Department of Justice Canada, 2005). Further, previous negative interaction with the criminal justice system was more likely to make victims wary of accessing services. Victims were less likely to seek out services as disappointment from previous interactions influenced their perceptions of victim-based services (Department of Justice Canada, 2005). Moreover, victim-based service providers interviewed in the Northern territories of Canada found that many victims had previously tried to reach out for support and were turned away. This negative interaction discouraged clients from reaching out again in the future (Levan, 2003, p. 136).

Trauma and Violence-Informed Care

Trauma sustained from a crime can have long-term impacts on a victim and/or survivor, regardless of whether the violence itself is on-going or occurred in the past. In recent years, the criminal justice system has renewed its interest in the development and implementation of trauma-informed practices to support victims and/or survivors of crime. Trauma and violence-informed care (TVIC) approaches are policies and practices that recognise the connections between violence, trauma, negative health outcomes and behaviours (Government of Canada, 2018). TVIC approaches expand on the concept of trauma-informed practice to account for the intersecting impacts of the criminal justice system and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life. As such, these approaches bring attention to broader, historical, social conditions and institutional forms of violence rather than seeing problems as solely residing in the person’s psychological state (Varcoe et al., 2016). The Government of Canada (2018) argues that this shift in language to include “violence” is critical as it underscores the importance of the relationship between violence and trauma. TVIC approaches can increase safety, control, and resilience for people who are seeking services in relation to experiences of violence and/or have a history of experiencing violence. They can also minimise harm and re-traumatisation to victims and/or survivors in a safe and respectful manner, acknowledging both individual and systemic violence (Varcoe et al., 2016).

Service providers, organisations, and systems may not be aware that they can cause unintentional harm to people who have experienced violence and trauma. Re-traumatisation can occur for victims of crime in a number of different ways. For example, a crime victim may feel re-traumatised when asked to re-tell their story of victimisation to different individuals and/or organisations throughout a criminal investigation. They may have to tell their story to the attending officer who was first to respond to the crime, to a doctor who treated their injuries, to a detective overlooking the criminal case, to a victim support worker to access victim compensation, and to a judge in a trial for the crime. This can be triggering to the victim and/or survivor.

TVIC approaches can help make systems and organisations more responsive to the needs of all people and to provide opportunities for practitioners to provide the most effective support to their clients. By practicing universal trauma precautions, service providers can offer safe care and support. Organisations can develop structures, policies, and processes that can foster a culture built on an understanding of how trauma and violence affect peoples’ lives. According to the Government of Canada (2018), there are four key principles for implementing TVIC approaches for service providers and organisations.

- understand trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples’ lives and behaviours;

- create emotionally and physically safe environments;

- foster opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection; and

- provide a strengths-based and capacity-building approach to support client coping and resilience

For example, an organisation that provides shelter for victims of violence may help prevent re-traumatisation by not requiring victims to disclose experiences of abuse in order to access housing. The organisation may hire staff with lived experience of partner violence who can better understand and support the victims they serve. Another example is the development of child advocacy centres to provide emotionally and physically safe environments for children who have been abused. These centres coordinate the investigation, intervention, and treatment of child abuse, while helping abused children and their non-offending family members navigate service systems and recover from experiences of violence (Government of Canada, 2018). By conducting joint interviews during the investigative phase of the work, this multidisciplinary team is able to minimise the number of times a child needs to re-tell their story of abuse while helping them feel comfortable and safe.

Media Attributions

- Posttraumatic Stress, Posttraumatic Growth, and Posttraumatic Change © American Psychological Association adapted by Norgaard & Roebuck is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Throughout this chapter we will include quotes from survivors drawn from a Canadian study on resilience and survivors of violent crime (Roebuck et al., 2020a, p.6). ↵

A disorder caused by exposure to extremely traumatic and stressful situations that fall outside the realm of normal, everyday, individual experiences.

A process of positive adaptation in the context of significant adversity. This involves navigating and negotiating tensions arising from adversity in a way that promotes personal well-being.

A framework for understanding positive changes that trauma survivors experience over time from the process of reflecting on and reframing their narratives.

A concept that incorporates posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth responses to trauma, while also exploring ambivalence and paradox in personal narratives about change.

The process by which victims feel victimized for a second time by the criminal justice system and/or legal process.

Policies and practices that recognize the connections between violence, trauma, negative health outcomes and behaviours.

A strengths-based framework grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma.