12. Cultural Criminology

12.6 The Methods of Cultural Criminology

Dr. Steven Kohm

6:45 AM. The clock radio was blaring the closing notes of some banal pop song from the 1980s when the announcer chimed in with the daily news and weather. It was going to be a hot one today—34 degrees Celsius and it wasn’t yet June! The announcer made a quip about global warming before moving on to the traffic report. Gridlock on Portage Avenue due to a protest in front of RCMP headquarters. The discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at a former residential school had been in the news this week. I wonder if this protest was related to that? It also made me think about the red dress hanging in my neighbour’s front yard [Figure 3]. I made a mental note to avoid Portage Avenue on my morning commute downtown.

I switched off the radio, but before my feet could hit the floor I picked up my phone and upon recognising my face, the device unlocked revealing a dozen unread emails. I quickly scrolled through to see if anything was urgent. The first message screamed in all-caps: WINNER!!!!!!! CLAIM YOURE FREE iPhone 11 Now!! I quickly swiped that message and several more like it in to the trash before concluding there wasn’t anything important to deal with.

After a quick shower and coffee, I punched the code into the alarm keypad by the front door, arming the system before heading to the garage for my bike. I gave the tires a quick squeeze to ensure they were fully inflated and checked to make sure my Abus Granit XPlus™ bike lock was secured in its holster. I marvelled at how heavy it was, and I recalled watching a YouTube video showing the same type of lock being cut with an angle grinder. The lock could be defeated, but it would take some time. Surely a thief would pass my bike over in favour of easier prey?

I cycled down the back alley and noticed some new graffiti on a dumpster behind an apartment complex. I was trying to decipher the colourful letters when I almost collided with a man pushing a shopping cart. The cart was filled with cans and bottles and all sorts of metal odds and ends. Before I could mutter an apology for nearly running into the man, I heard shouts and I looked to see a uniformed security guard running from the apartment complex gesturing at the man with the cart. I decided to keep riding and ignore the ruckus.

A bit farther along my ride, I noticed several tarps and tents strung up under a highway overpass, and I wondered who might be living there. I also noticed the colourful mural dedicated to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls on the side abutment of the overpass. While reading the names of the women depicted in the mural I saw that someone had added a new graffiti tag on the overpass that read “FUCK BANKS.” The whole scene made me feel uneasy, and I quickly pedaled away [Figure 12.4].

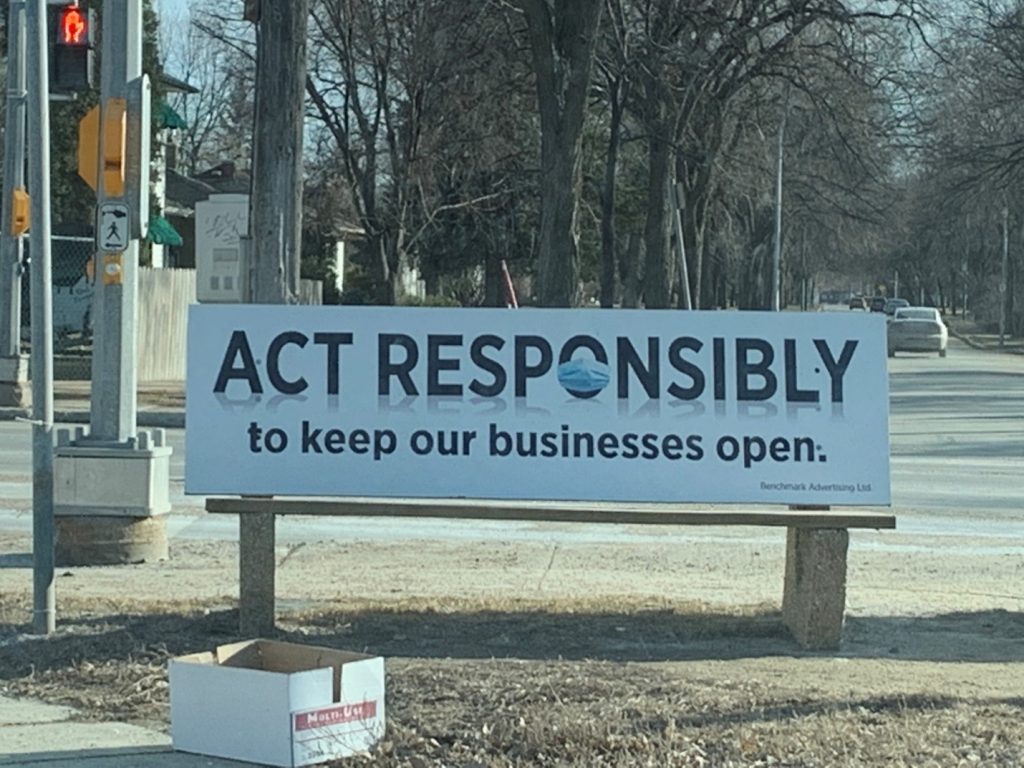

Later, while stopped at a red light, I noticed an advertisement on a bus bench had been recently vandalised. This bench bore the same message since the very start of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Act Responsibly to keep our businesses open” [Figure 12.5]. Today, it gave me a chuckle to see that above this slogan someone had added “Government should” in black marker. The light turned green, and I continued on.

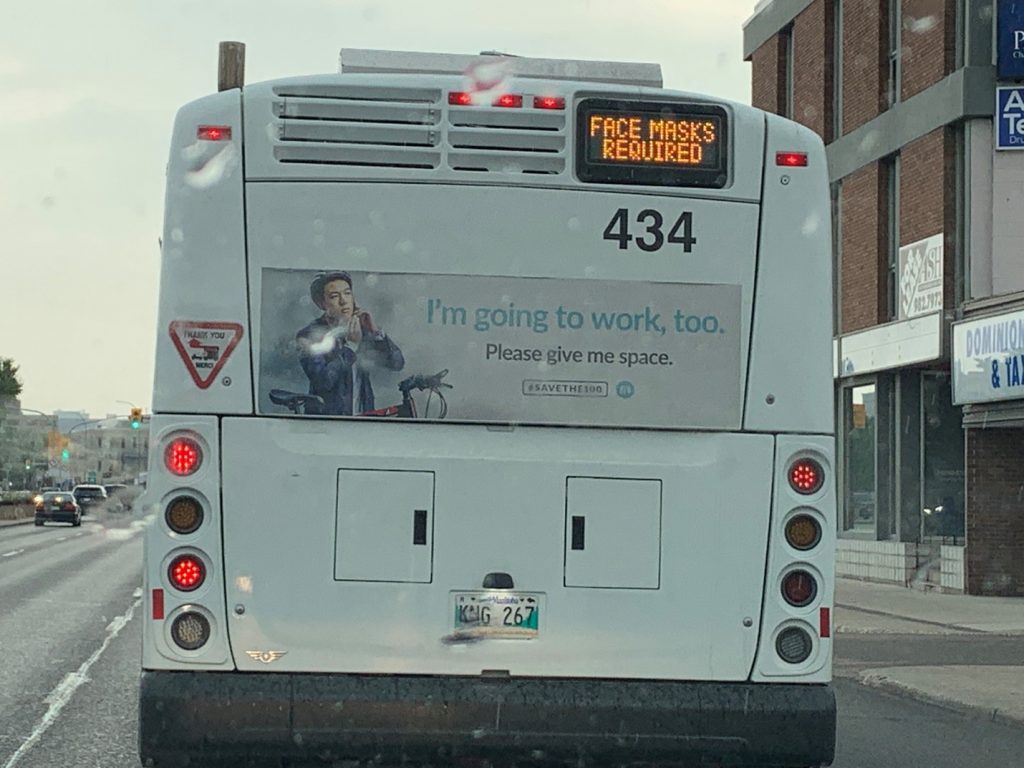

Part of my commute to work follows a bike lane along a busy stretch of road downtown. Aside from a white line of paint on the asphalt, nothing separates cars from cyclists and I felt a bit nervous, especially at intersections where cars sometimes turn in front of me without looking. Sometimes drivers even yell and make threatening gestures or cut me off in traffic [Figure 12.6]. Today, a car pulled into the bike lane and stopped suddenly in front of me. I braked hard to avoid a collision and looked on incredulously as a well-dressed man stepped out of the car without even acknowledging me. “What the hell?” I shouted angrily, gesturing toward the no parking signs. “Fuck you!” he replied, and all of a sudden he reached into his car and produced a tire iron. I quickly pushed my bike up onto the sidewalk and pedalled hard past the scene. My heart was pounding and I was shaking just a bit.

“Just another fucking Monday.” I muttered to myself as I made the rest of my way to work.

This vignette is meant to illustrate how everyday moments contain within them opportunities to think about how crime and control are woven into our daily lives, as well as the way power is both exercised and resisted from below in late modern life. It also shows how crime and control play out through moments embedded in culture. Take a moment to think about the range of crimes implied by this anecdote. Everything from minor graffiti and the pilfering of scrap metal, to online fraud, to state sponsored acts of murder and colonial genocide all weave their way in and out of our everyday culture, as do acts of resistance to the exercise of control. Individuals with power and privilege can rely on private security and home alarm systems for protection, while those who are unhoused are vulnerable to exploitation and criminalisation for engaging in acts of survival. Conflicts between motorists and cyclists boil over into violent confrontation, and protests take the form of traffic blockades, pop-up art installations and guerilla graffiti aiming to subvert government messaging. Imagine your own day and think about how crime and justice weave seamlessly into your own lives and into culture.

For students trained in social science, this sort of criminology of the everyday may not seem like a method of analysis at all. However, cultural criminology reaches back into the history of the discipline to reclaim earlier approaches to studying crime. Looking to the origin of the discipline, we can see that “many of criminology’s foundational works emerged out of an idiosyncratic, impressionistic approach to ethnographic inquiry” (Ferrell, 2004, p. 295). Regarded as the intellectual foundation of American criminology, the Chicago School of Sociology in the early twentieth century epitomised this idiosyncratic approach. Chicago School sociologists undertook their research far from their university offices and viewed the city as an unknown territory ripe for scholarly investigation. They used a form of field research adapted from anthropology called ethnography that involved long-term interaction and the observation of cultural groups in their natural settings (see chapter on Methods and Measuring Crime) to study unconventional groups and behaviours found throughout the city—from Depression-era hobos (Anderson, 1923) to juvenile delinquents (Shaw, 1930). Frederic Thrasher spent seven years undertaking immersive field research before writing his 571-page book The Gang (1927). Robert Park, a leading figure of the Chicago School, was a former newspaper reporter and used a similar approach to gathering stories from those living in the city. These rich, detailed and experiential accounts of human behaviour nowadays seem almost romantic and hardly resemble contemporary academic criminology. Also, it seems incredibly impractical to spend seven years on field research. Can these approaches be updated and modernised for late modern times when the world appears to be moving faster and faster?

In answer, many cultural criminologists propose that researchers engage in instant ethnography—an approach that recognises that late modern life unfolds in unpredictable and haphazard ways. Researchers can gain important insights into crime and control by observing these fleeting moments which appear when researchers take the time to simply look around. As the opening anecdote illustrates, keeping our eyes open to the way crime and control seeps into our day-to-day culture can provide insight lacking in more traditional and planned approaches. Cultural criminology celebrates and uses the unpredictability of late modern life to analyse and offer social and political critique about crime and control. Take a few moments to look around your world today. You may be surprised at what you see.

Media Attributions

- A Red Dress: Art or Politics? © Dr. Steven Kohm is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Never Forgotten © Dr. Steven Kohm is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- (Government Should) Act Responsibly © Dr. Steven Kohm is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Please Give Me Space © Dr. Steven Kohm is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

is a method of field research pioneered in cultural anthropology that involves immersive and lengthy interaction with cultural groups in order to learn about their ways of life and beliefs. In the nineteenth century, ethnography was used predominantly to study cultures in distant and non-western contexts. However, through the twentieth century, scholars in the social sciences began using this method to study subcultural groups closer to home. Ethnography involves participation in aspects of the culture under study as well as lengthy periods of contact and the development of mutual trust and respect. A common critique of this method is that researchers may grow too close to their subjects, and lose scholarly, detached perspective. A considerable strength of the method is that researchers gain deep, detailed, and realistic knowledge about a culture by adopting the perspective of insiders. Ethnography is a favoured method of cultural criminology, but it is not the only approach in this perspective.