17. Restorative, Transformative Justice

17.5 Justice Stakeholders

Dr. Alana Marie Abramson and Melissa Leanne Roberts, M.A.

Restorative justice aims to meaningfully include three stakeholders in the justice process: victim, offender, and community.

Victims

The focus of the current justice system is on apprehending, prosecuting, and sentencing people who cause harm or “offenders.” Only a fraction of the over $30 billion dollars spent on justice in Canada each year is directed towards victims. The Victims Rights Movement began in the 1970s and brought awareness to the exclusion victims face and the secondary victimisation they experience. Secondary victimisation refers to the harm victims may experience after reporting a crime. This harm could be perpetuated by members of the criminal justice system, the medical system or the victims support network of friends and family. It can take the form of victim blaming, not being believed, or treating victims with scorn, disrespect, mistrust, or suspicion. Secondary victimisation can also be experienced as a result of the investigation by police or providing testimony in court. In both these examples, people are asked to relive their victimization experience and may even have their stories/truth/experience called into question by criminal justice professionals. In cases of physical or sexual violence, the medical examination and evidence collection process can be incredibly traumatic for victims.

Restorative justice attempts to minimise the risk of secondary victimisation by placing victims’ needs at the centre of the justice process. According to Achilles and Stutzman-Amstutz (2006, p. 217), the promise of restorative justice is:

- an elevation of the victim’s status,

- identification of the victim as the person that the offender is first and foremost accountable to,

- greater and more meaningful participation in the legal process,

- a focus on harm to provide a necessary identification of victim needs as the starting point of justice, and

- the creation of a space where victims in the aftermath of trauma can control the process of justice.

Offenders

From a restorative justice perspective, harming another person creates obligations on the part of the harm-doer to take responsibility for what happened and to be accountable through making things as right as possible. Beyond punishment and rehabilitation, offenders are invited to take part in acts of reparation/restoration by being willing to repair both material and symbolic dimensions of harm. Material reparations might include the repayment of monies stolen or financial restitution of items lost, stolen or damaged. Symbolic reparation could involve acts of service in the form of volunteer work or personal service to the victim to repay the costs related to the crime. This could also mean apologies, recognition of wrongs, and displays of contrition. Restorative justice also means that offenders consider how to minimise the risk further through making amends and demonstrate changed behaviour over time.

The obligations created by harm are often too vast for the victim or offender to address alone. This is where restorative justice questions can expand the circle to ask, “Who else’s obligations are these?” Communities of care that include both informal and professional supports can assist in addressing the immediate, intermediate, and long-term needs arising from incidents involving harm.

Community

Community has multiple facets and can be considered geographically (where the harm took place) or it could be socially defined in terms of who was impacted (Schiff, 2007). From a restorative, transformative perspective, communities are obligated to play a role in both providing support to those directly impacted and holding themselves and others accountable for creating the conditions for crime and harm to occur. The larger and more socially disconnected a community is, the harder it will be for obligations to be undertaken. The question becomes: To what extent is the wider community obliged and what role should the community play in restorative justice. For a further explanation of community accountability, check out restorative justice advocate and practitioner Phil Gatensby from the Yukon territory in The Problem With Youth – It’s Adults!

A community can include anyone who feels connected to the harm or the people involved in the harm. Community members—those directly or indirectly impacted by the harm—have individual needs that often mirror victim needs. Community members may express other needs such as:

- recognition of their position as victims

- reassurance that what happened was wrong, that something is being done about it and that steps are being taken to discourage its recurrence

- information about what happened and the response

- avenues for building a sense of community and accountability

- encouragement to fulfill responsibilities for the well-being of victims and offenders

- engagement in activities that promote community restoration and social pride (Obi et al., 2018, pp. 6-7).

Restorative justice approaches encourage collaborative, collective, community-based responses that aim to address the conditions that create harm and the impacts of harm. The obligations communities have when harm occurs include:

- responsibility for communicating the harm that occurred, its degree and expectations for appropriate repair;

- communicating standards of expected behaviour, norms, and values;

- collective ownership of the causes of harm and work together on how to address it;

- supporting the completion of reparation agreements that result from restorative justice processes;

- creating a safe environment for community members, including the victim and the offender;

- being informed of available services to support victims and offenders;

- mentorship and support (materially, physically, emotionally) to victims/survivors and offenders; and

- developing reintegration strategies (Schiff, 2007, pp. 236-238).

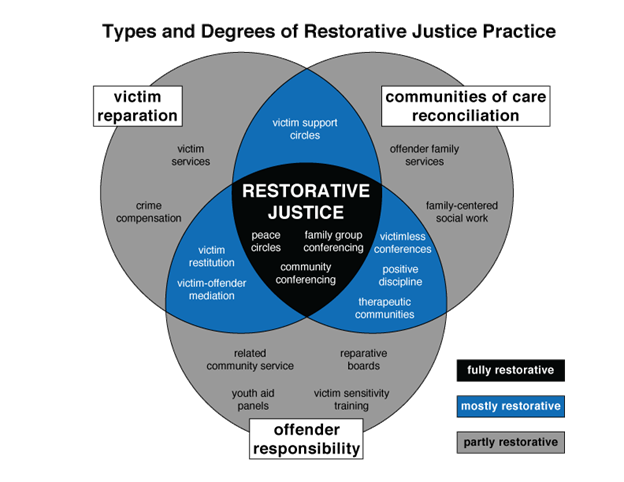

Some restorative justice theorists believe that all three stakeholders – victim, offender, community – must all be involved for a process to be considered fully restorative. See Figure 17.2 for a visual representation of the types and degrees of restorative practice and an illustration of the interplay of these three stakeholders.

Media Attributions

- Types and Degrees of Restorative Justice Practice © Paul McCold and Ted Wachtel adapted by Alana Marie Abramson is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license