3 Incorporate First Peoples’ Principles of Learning to Support Tutees

As we consider the elements of our tutoring, an important consideration is Indigenizing our practice. In this work we aim to make our tutoring respectful and culturally relevant for Indigenous tutees, as well as enrich the experience of all of our tutees by expanding the knowledges and ways of being that are available within the tutoring dialogue. In this practice, we also seek to be reflective about our own journey of reconciliation and relationship with the land we are on and the Nations that have stewarded it since time immemorial.[1]

Situate Ourselves[2]

In many Indigenous communities, it is important to begin our relationship and dialogue with one another by situating ourselves. This practice includes acknowledging our ancestry, community, and family background, as well as how we came to be on the land where we now live. Situating ourselves helps us to understand our relationships with Indigenous peoples and ways of knowing, as well as the land we are on. Before you move on in these materials, take a moment to situate yourself, either in writing, or by sharing with your tutor colleagues.

Incorporate First Peoples’ Principles of Learning to Support Tutees

The First Peoples’ Principles of Learning, presented by the First Nations Education Steering Committee (n.d.) outline principles that inform learning in Indigenous contexts. It is important to note that these represent a pan-Indigenous approach, and that the culturally-specific values of each community should be considered alongside these more general principles.

- Learning ultimately supports the well-being of the self, the family, the community, the land, the spirits, and the ancestors.

- Learning is holistic, reflexive, reflective, experiential, and relational (focused on connectedness, on reciprocal relationships, and a sense of place).

- Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one’s actions. Learning involves generational roles and responsibilities.

- Learning recognizes the role of Indigenous knowledge.

- Learning is embedded in memory, history, and story.

- Learning involves patience and time.

- Learning requires exploration of one’s identity.

- Learning involves recognizing that some knowledge is sacred and only shared with permission and/or in certain situations.

Source: http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Activity: Reflect on the principles presented above. Choose three principles, and identify how you can implement them as you work with your tutees.

| Principle | How I will implement this with tutees |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apply Whole Person Learning

As we explore the First People’s Principles of Learning, we notice the emphasis on holistic learning. In other words, learning involves all of who we are, including our physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual selves. This contrasts with dominant Westernized perspectives on learning that can place excessive focus on learning as a cognitive process.

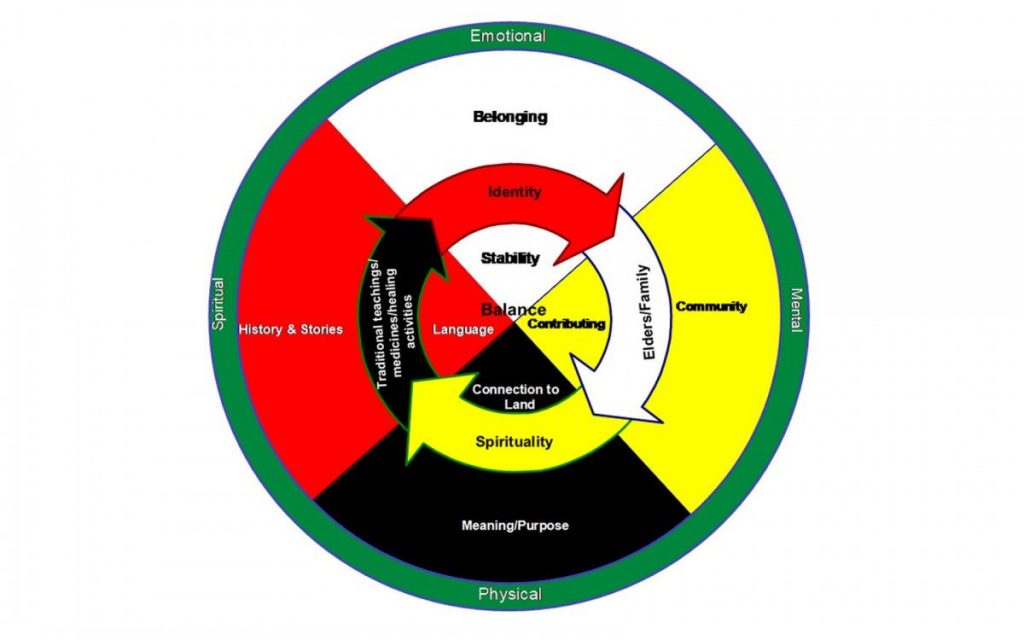

The Medicine Wheel is an important teaching of many Indigenous communities. A Medicine Wheel includes four quadrants; many Anishinaabe knowledge keepers draw on these quadrants, relating them to the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual aspects of our being (Yearington, 2010, as cited in Morcom and Freeman, 2018). The Medicine Wheel can also symbolize balance and interconnection.

The image below comes from the University of Manitoba. You are invited to reflect on this image, noticing what resonates with you. How have you experienced the elements, values, and practices pictured on the Medicine Wheel in your own journey as a learner?

Link to image source: https://news.umanitoba.ca/look-to-the-medicine-wheel-for-mental-health-elders-advise-in-first-nations-study/

As tutors, you have already learned to follow the practice of many educators in creating learning objectives for your tutoring sessions based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. These learning objectives traditionally include knowledge, skills, and attitudes. LaFever (2016), a Settler scholar, uses the Medicine Wheel as a model for adding the spiritual dimension to our consideration of whole-person learning. She suggests that the spiritual dimension includes:

- honouring our own presence as learners through mindful awareness of our reactions and emotions.

- building supportive relationships with respectful attention to our identities and those of others.

- growing a sense of belonging, both to the university and broader community.

- understanding how our learning connects with our broader sense of purpose and community actions.

Activity

Reflect on how you honour whole person learning, and how you can create a tutoring environment that encourages tutees to do the same. While a chart is presented below, you are encouraged to select a method of reflection that best meets your needs. This could include a journal, freewriting, or another artistic representation. If you are completing this section in a group setting, you may follow this activity with a sharing circle.

| Dimension of Personhood | How I Honour this Dimension | How I Can Support Tutees in Honouring this Dimension |

| Physical |

|

|

| Mental |

|

|

| Emotional |

|

|

| Spiritual |

|

Integrate Two-Eyed Seeing

Etuaptmumk, Two-Eyed Seeing, is a concept articulated by Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall, rooted within broader Mi’kmaq understandings of learning and seeing the world. Two-Eyed Seeing is

the gift of multiple perspective treasured by many Aboriginal peoples and explains that it refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing, and to using both these eyes together, for the benefit of all. (Bartlett et al., 2012, p. 335).

Two-Eyed Seeing demonstrates respect and honour for Indigenous Knowledges. Rather than attempting to synthesize Indigenous and Western perspectives, Two-Eyed maintains the integrity of each way of knowing, drawing from the strengths of both. Elder Albert Marshall also describes this process with the metaphor of weaving. As in a woven basket, where each strand can be distinctly seen while creating a product of beauty and value, Two-Eyed Seeing aims to create a better understanding of the world by actively using multiple ways of knowing. Marshall emphasizes that Two-Eyed Seeing is intended to motivate people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, to work towards improving the world for the Seven Generations that follow us (Bartlett et al., 2012).

Activity: Watch: TEDx Talks. (2016, June 13). Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing | Rebecca Thomas [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bA9EwcFbVfg

In this video, Rebecca Thomas, a Mi’kmaq educator, Poet Laureate for the Halifax Regional Municipality, and Coordinator of Indigenous Student Supports at Nova Scotia Community College, shares her experience with Two-Eyed Seeing.

For reflection:

- How would you use the concept of Two-Eyed Seeing to support a tutee that identifies as Indigenous?

- How can Two-Eyed Seeing enhance learning for all tutees?

Connect Tutees with Indigenous Campus and Learning Resources

- The Gathering Place: KPU’s Gathering Place is located on Surrey Campus. The goal of the Gathering Place is to create an inviting gathering place for all students: a space that supports the social and educational activities associated with attending KPU in an environment that recognizes the important contribution of the Kwantlen, Semiahmoo, Tsawwassen, Qay’Qayt, Katzie, and all other Indigenous Nations (Information from: https://www.kpu.ca/indigenous/gathering-place).

- Indigenous Research and Information Literacy: As a tutor, you may work with students in Indigenous studies courses, or who are conducting research using Indigenous knowledge. KPU librarian Rachel Chong has created a series of videos to support learning about Indigenous information literacy. Indigenous information literacy includes finding sources by Indigenous authors, conducting research in Indigenous communities according to appropriate protocols that incorporate reciprocity, and citing knowledge from Elders and traditional knowledge keepers. The videos below will introduce you to concepts you may encounter in your practice as a writing tutor. You can find the full video series here. This information is also available in a Pressbook: https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/indigenousinformationliteracy/.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter have been adapted from:

Anaquod, J. and Page, C. (Forthcoming). Two-eyed Seeing: Incorporating Indigenous and Intercultural Perspectives in Curriculum Design. Kwantlen Polytechnic University

References

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

First Nations Education Steering Committee (n.d.) First people’s principles of learning. http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

LaFever, M. (2016). Switching from Bloom to the Medicine Wheel: creating learning outcomes that support Indigenous ways of knowing in post-secondary education. Intercultural Education, 27(5), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2016.1240496

Morcom, L., & Freeman, K. (2018). Niinwi-Kiinwa-Kiinwi: Building non-Indigenous allies in education through Indigenous pedagogy. Canadian Journal of Education, 41(3), 808–833.

- We (Christina Page and Alice Macpherson) write these materials as Settler scholars. We are grateful for the knowledge that has been shared with us, and we share it in turn to the best of our understanding. We take responsibility for any errors as we seek to grow in our learning. ↵

- We would like to express our gratitude to Rachel Chong, a Métis librarian, for sharing this practice with us. ↵