4 Develop an Intercultural Tutoring Practice

Your Culture Activity:

Take a few minutes to jot down some thoughts about yourself. Then spend the next five to ten minutes sharing these thoughts with one other person.

- How do you define ‘Culture’?

- How do you identify yourself culturally or ethnically? What are the other “small cultures” (Holliday, 1999) that make up your identity (e.g., gender, sexual orientation, religion/spirituality, language)?

- What do you enjoy or appreciate most about your culture(s)?

- What assumptions do people make about your culture(s)?

Note: Prepare to discuss with your cohort members and Trainers.

What is Culture?

Culture is dynamic – neither fixed nor static. It is a continuous and cumulative process that is collectively learned and shared by a group. You can see it through the behaviour and values exhibited by a group of people. Culture includes what is creative and meaningful in our lives. It has symbolic representation through language and activity. It is that which guides people in their thinking, feeling and acting.

Culture Is Not:

Culture is not just artifacts or material used by a people or a “laundry list” of traits and facts. It is not biological traits. Although it is attractive, it is not the ideal and romantic heritage of a people as seen through music, dance, holidays or a higher class status derived from knowledge of the arts, manners, literature. Finally culture is not something to be bought, sold or distributed.

Why It Is Important To Know About Culture?

Culture is a means of survival. All people are cultural beings and need to be aware of how culture affects people’s behavior. Culture affects us everywhere including in the classroom, at home and at work. Culture also affects how learning is organized, how work and school rules and curriculum are developed, and how teaching methods and evaluation procedures are implemented. Cultural awareness and acceptance can ease communications at school and in the community. Culture is an integral part of Canadian society.

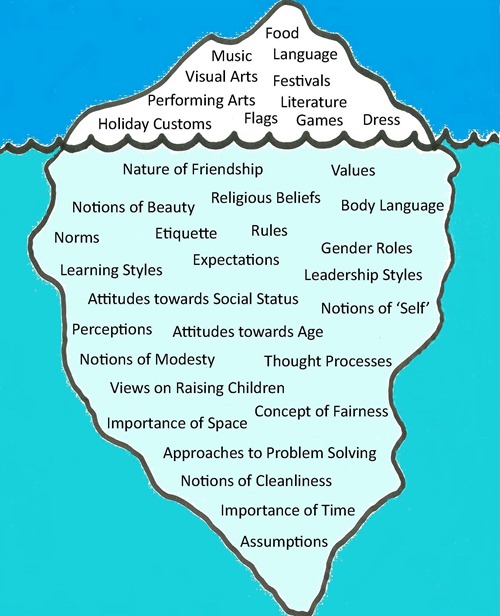

Iceberg Model of Culture

Like an iceberg, what we see is only a small part of the whole. Culture is complex.

Adapted from Edward T. Hall (1976)

Developing a Cross-Cultural Perspective

Culture can be very different from person to person. Knowing the perspectives of others will help you to interact respectfully with them.

Dimensions of Culture

Culture in Ourselves

Seeing culture in ourselves involves perception or knowledge gained through our senses and interpreted internally. It is not always obvious since it is shared socially with those we meet on an everyday basis. It helps us to understand and avoid areas of conflict, and allows us to learn through contrast. This reflection on culture in ourselves implies that thought processes occurring within each of us also occur within others, but may take on a different shape or meaning for that person.

Culture in Others

We have to see the difference between ourselves and others to be able to see someone else’s culture. Our cultural perceptions can involve a certain degree of ethnocentrism, the belief that our own cultural ways are correct and superior to others. This is natural and occurs in each of us. While it helps to develop pride and a positive self-image, it can also be harmful if carried to the extreme of developing an intolerance for people of other cultures. It is perhaps best represented by the concept of cultural relativism which is the belief that there are many cultural ways that are correct, each in its own location and context. It is essential to building respect for cultural differences and appreciation for cultural similarities.

Respectful Interaction

Respectful interaction is a key element to resolving and utilizing the immediate conflicts that may arise when you and your personal culture come into contact with the diverse needs of others. The communication skills of active and empathic listening and paraphrasing followed by effective questioning and feedback techniques are all elements of this interaction. Personal flexibility and adaptability to the needs of others is a necessary trait in a multicultural environment.

Being Self-Reflective and Reflexive

It is important to locate oneself in terms of culture of origin, culture of choice, gender, age, income, education, and personal values. What do these mean in terms of your inherent privileges or disadvantages, your empowerment or lack of it, your social position and prospects? How does this impact those that you work with?

Reflexivity refers to reciprocal and circular relationships between cause and effect. A reflexive relationship works with both the cause and the effect of interactions as people are affecting one another in a situation.

Committing to Intercultural Development

Student Intercultural Development Self-Reflection Guide

Intercultural development is a lifelong journey that shapes ways of thinking, emotional responses, ways of relating to others, and ways of advocating for change in the world. Intercultural growth occurs through participating in intercultural life experiences, reflecting on how these experiences shape us, and identifying steps for ongoing development.

This self-assessment includes reflection questions in five intercultural domains. Honestly reflect on your current level of development. This process will help you to identify strengths that support you in effective cross-cultural relationships and to set intentions for ongoing development.

Affective (attitudes and emotions that support interculturality)

- I am curious about other people, other contexts, and other ways of seeing the world.

- I am open-minded when I explore new situations.

- I can withhold judgement when I encounter a situation I do not fully understand.

Cognitive (ways of thinking interculturally)

- I am a lifelong intercultural learner.

- I can avoid stereotypes when describing the cultural identities and values of others.

- I can identify multiple culturally-influenced points of view on an issue.

- I can tolerate an ambiguous situation where the right action/ answer is not immediately clear.

Intrapersonal (internal intercultural development)

- I can identify the factors that contribute to my identity(ies).

- I can identify my strengths, abilities, and limitations.

- I engage in regular self-reflection to support my ongoing journey of growth, change, and development.

- I can recover from setbacks and mistakes in intercultural relationships, continuing to actively engage with others.

Relational (intercultural development expressed in relating)

- I can develop relationships with others from a different cultural background than my own.

- I can adjust my communication style when interacting across a linguistic difference.

- I can adjust my way of relating to demonstrate sensitivity for someone else’s cultural preferences.

- I can express empathy in an intercultural situation.

- I can relate to others from a place of equality, working to eliminate any power imbalances in the relationship.

Social (intercultural understanding that supports equity and justice)

- I am aware of how my identities influence relationships in my own and in other cultures.

- I am able to challenge discriminatory ideas.

- I am able to identify actions to take when I observe a social injustice.

- I am able to support other communities’ efforts towards equity.

Informed by: King and Baxter Magdola (2005), Deardorff (2006), Dervin (2016) and Foronda et al., (2016).

Supporting Tutees Through Intercultural Tutoring Communication

Culture Stress

Entering a new cultural environment is a demanding, challenging, and stressful process. It includes the mental, physical and emotional adjustment to living in a new context, as well as the coming to terms with different ways of approaching everyday living. This process embraces everything from fundamental philosophical assumptions (one’s worldview) to daily chores.

All students experience some level of adjustment-related stresses as they go from high school to university or from the world of work to the world of education. Some students have even more of a shift when they come from a different country to study in Canada (or when a student travels to another country from Canada). Your tutee may be experiencing culture stress for a variety of these reasons.

Some of the signs of culture stress include:

- Homesickness.

- Boredom.

- Withdrawal (spending most of your time in your room, only seeing other students from your background, avoiding people who are different from you).

- Negative feelings and stereotyping of others.

- Inability to concentrate.

- Excessive sleep or insomnia.

- Compulsive eating or drinking or lack of appetite.

- Crying uncontrollably or Outbursts of anger, irritability.

- Physical ailments, such as frequent headaches or stomachaches.

It is helpful to know that most students adapt successfully. When your tutee seems to be experiencing culture stress, tutors can be encouraging and empathic but you are not counsellors and need to refer those students who are struggling with this shock to other resources and departments as needed.

Helping your Tutee Adapt to a New Culture

When adjusting to a new culture, individuals often move through various stages, including euphoria, rejection of the new culture, acceptance of the new culture, and adaptation. These stages are typical of many students, but it is important to realize that individual experiences of culture stress may vary, and to seek to meet to tutees where they are.

- Euphoria (Tutors can share enthusiasm with their tutees).

- Fear, Anxiety, Rejection (Tutors listen and refer to other resources and support systems as needed).

- Acceptance and Adjustment (Tutors encourage a positive outlook as tutees adjust).

- Resolution (Tutors and tutees are normal and focused on coursework).

Building a Cultural Bridge

To increase your effectiveness when working with people from a variety of cultural backgrounds:

Be informed.

Having some knowledge of another’s cultural background can result in useful insights to areas of potential cross-cultural conflict.

Be interested (in the world of personal meanings).

Aspects of the individual that are under-validated in the host culture can be validated in a discussion or interview. For instance, you may ask the meaning of a person’s name, family history, attachments, etc.

Be flexible and be an astute listener.

For the person communicating in a second language, simply feeling understood can reduce anxiety. Show respect for varieties of English that are different from your own.

Adjust your communication style responsively

Avoid using idioms and cultural references that may be unfamiliar to your tutee, or provide explanations as you use them. Use clear and simple language.

Be informative (a cultural interpreter).

Your role may include acting as an interpreter of the academic culture of the university and beyond for a tutee.

Take your cues from the other person and ask!

Use these techniques when you can tell whether the other person is comfortable with them. If you are unsure you can ask, “Is this a good time to talk?” “Would it be all right if I asked you about your name?” etc.

Using Academic Literacies to Explain Academic Culture

When working with tutees, it is important to avoid “deficit thinking” that positions tutees as lacking in the qualities needed for academic success. One positive approach to exploring academic culture with tutees is to use language and concepts from Academic Literacies (Lee & Street, 1998). Academic Literacies is an approach to understanding how individuals move into a new academic culture. The model states that all students enter university, and specifically their university program as novices and learners of a new “academic language” and way of communicating.

The Academic Literacies model assumes that language and ways of communicating are contextual, not universal. It avoids stigmatizing other ways of communicating and using language as “wrong”, and instead emphasizes that there are multiple good ways of making meaning using language, and that they are specific to certain contexts and disciplines.

Here are some example statements that demonstrate the use of academic literacies when working with tutees:

- In science writing, we often avoid using first person (“I”) pronouns, because writing objectively is valued in the sciences.

- In Canadian business writing, we usually use the term ____ instead of ____.

- When writing nursing papers, instructors usually prefer that we avoid long direct quotations, and that we paraphrase the ideas from our readings instead. Let’s take a look at this example of a nursing paper — what do you notice about how the author uses ideas from other sources?

- Many instructors in Canada expect communication to be very direct, and don’t consider this too strong or rude. This is why we put a very clear and direct thesis statement early in the paper introduction.

Activity:

- What ways of communicating/ making meaning are valued in the courses that you tutor?

- Create 2-3 sample statements that you might use with tutees using concepts from the Academic Literacies model.

Attribution Statement

The content in the Committing to Intercultural Development section of this chapter is adapted from: Page, C. (2021). Interculturalizing the curriculum. Kwantlen Polytechnic University. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/interculturalizingcurriculum/

References

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: A theoretical and methodological toolbox. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D.-L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

Holliday, A. (1999). Small cultures. Applied Linguistics, 20(2), 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/20.2.237

King, P. M., & Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 571–592. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0060

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364