5 Practice Cultural Safety and Anti-Racist Tutoring

Many tutors are drawn to the work of tutoring because of a strong desire to make a difference. We want to help our tutees succeed academically and experience a sense of belonging in the university. As we work with our tutees, we often have firsthand experience of the ways that our tutees experience the university as a difficult space that may not fully offer equitable opportunities for learning, and that may not support all aspects of cultural identity. This is why the work of tutors can also be considered as an act of social justice. The Canadian Writing Centres Association (2021), states that,

[Learning] centres recognize that expressions of ideas, opinions, and thoughts are political acts. Speaking, writing, and visual expression both shape and reflect patterns and habits of thinking within communities and institutions, and these practices of speaking and writing are connected to histories of subjugation and coercion that have privileged some and marginalized others (Garcia, 2019). Teaching and supporting [tutees], then, is also a political act; as [learning] centres are founded as acts of social justice, each tutoring session is an act for social justice.

Part of our work towards tutoring as a socially just space involves the practices of culturally safe and anti-racist tutoring.

Practicing Cultural Safety

The American Psychological Association (2020) defines cultural sensitivity as “awareness and appreciation of the values, norms, and beliefs characteristic of a cultural, ethnic, racial, or other group that is not one’s own, accompanied by a willingness to adapt one’s behaviour accordingly.” Cultural sensitivity is a core value that informs our interaction with tutees, and positions us as lifelong learners who seek to learn from each of our tutees about cultural values, practices, and ways of interaction that support their learning and well-being (Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998). In contrast, cultural un-safety is a subjective sense that one’s cherished values, goals, language, identity, and ways of life are denigrated or threatened in an encounter, or that one is being asked to venture into a foreign culture without knowing how to function in it and without positive accompaniment. Unsafe cultural practice is any action which demeans, diminishes or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of people.

Creating cultural safety requires both openness to learning from others, and a commitment to self-reflection on how our own identities shape our ways of understanding the world and interacting with others. Often, we may be unaware of how our cultural and social locations shape our assumptions and expectations. For example, we are deeply shaped by the educational systems we have participated in our youth and adulthood, and these systems may shape our expectations of how to learn in an academic context. We may not fully realize that these assumptions may not be shared by all of our tutees.

Cultural safety addresses power relationships between the service provider and the people who use the service. Practicing cultural safety asks us to carefully reflect on the power dynamics that may occur within our relationships with tutees. For example, even as peer tutors, we recognize that our tutees may feel vulnerable, especially at the beginning of the relationship, and that our knowledge of academic processes places us into a leadership position within our roles. Cultural safety also asks that we consider how power affects intercultural relationships within our institutional contexts.

Canadian Human Rights law forbids discrimination on a number levels, including: race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex (including pregnancy and breastfeeding), sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, marital status, family status, disability (physical and mental), and genetic characteristics. Your awareness of your personal background and biases that may exist will help you to support a tutoring environment that is free from discrimination and safe for all.

Ethnically/Culturally Sensitive Attitudes and Values

The following list is adapted from material by Mercedes Tompkins and Casea Myrna Vasques, from an interview with Elva Caraballo (1996).

|

DO |

DO NOT |

|

Do with |

Do for |

|

Come alongside |

Lead |

|

Assist |

Control |

|

Provide input |

Demand |

|

Facilitate |

Determine |

|

Provide additional resources |

Impose additional requirements |

|

Encourage |

Mandate |

|

Respect |

Condescend |

|

Show concern |

Paternalize |

|

Empathize |

Sympathize |

This is not very different from how most people want to be treated and is a key component of how tutors need to act to be effective. The interesting thing is that many people believe that the process by which we interact with others should be different from how we want to be treated. It is often useful and always polite to respectfully inquire how a person wishes to be treated or helped.

Anti-Racist Tutoring Practice

Anti-racist action asks for an additional layer of analysis, as we consider how systems, practices, and processes may cause disadvantage and harm to non-dominant groups. The Ontario Anti-Racism Secretariat defines anti-racism as “the practice of identifying, challenging, and changing the values, structures and behaviours that perpetuate systemic racism”. This extends beyond an understanding that education is a cultural practice, to understanding the ways in which some are advantaged, and others disadvantaged, within this cultural system. Anti-racist educational practice, including tutoring, includes reflecting on our own relationship with academic cultures, learning how racism affects ourselves and those around us, and taking focused actions to challenge the impacts of racism.

Anti-racist tutoring emphasizes that, because of the systemic nature of racism, it is not sufficient simply to avoid active acts of discrimination; actively challenging racism and the systems that support it is required. Singh (2019) writes that anti-racist practice involves different processes for white people and people of colour. For white people, this work involves acknowledging participation in a racist system, having internalized it as “normal” through the lens of the dominant culture. This work also includes acknowledging power and privilege, questioning the dominant culture system, and taking active steps to learn the full history of other racial groups. Anti-racist work for people of colour may include challenging internalized racism and stereotypes, and developing a broader knowledge of other ethnic groups, their histories and struggles.

Anti-racist tutoring practices require both a commitment to personal growth, learning, and internal change, as well as an active commitment to shift tutoring practices and ways of relating to tutees. Action steps that inform tutoring practice include considering how expectations of an “ideal” tutee may be racially biased and creating a supportive environment where tutees can question biased content or practices (Wheaton College Massachusetts, 2021).

Activity

What are the similarities and differences between cultural safety and anti-racism? How does each contribute to your understanding of tutoring practice?

A Framework for Growing in Anti-Racist Practice

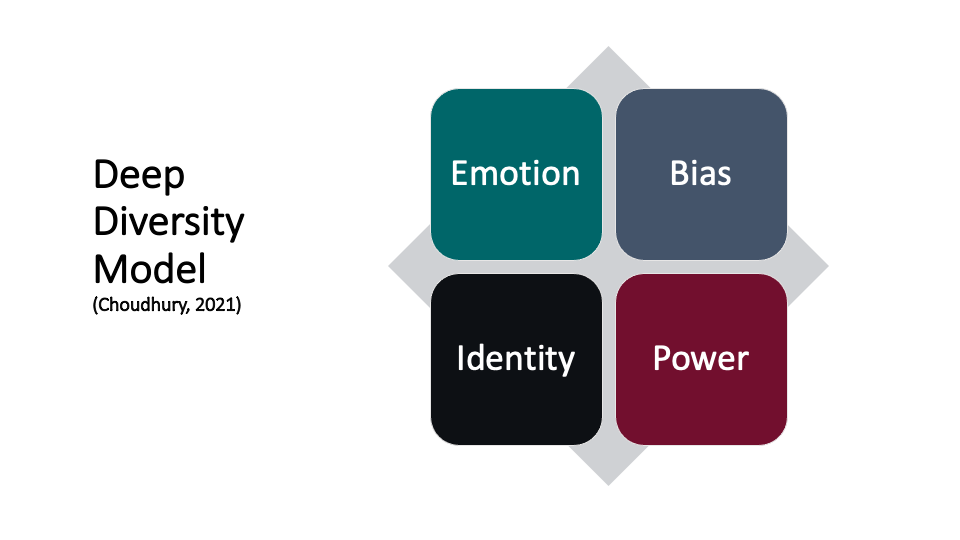

Shakil Choudhury (2021) presents the Deep Diversity framework as a way to frame our personal growth towards an anti-racist way of being in the world. Choudhury identifies four dimensions of understanding and practice.

| Element of Deep Diversity | Action Steps for Growth |

| Emotions: Understand that anti-racism work requires non-judgementally recognizing emotional reactions towards those like and unlike ourselves and recognition of how emotions spread throughout a group. |

|

| Bias: Recognize that all people have implicit biases. They are a common human reality, but are changeable with focused work. |

|

| Identity: Recognize the ways in which we are shaped by our desire to belong to our “in-group”. |

|

| Power (Systemic): Recognize that racism and other forms of discrimination arise from the historical and current application of power by the dominant group against non-dominant groups. |

|

| Power (Personal): Develop our strategies to use our own social position, relationships, and influence to create positive change. |

|

Activity: Drawing on the Deep Diversity framework, identify one concrete step you plan to take in your own journey towards anti-racist tutoring practice.

Attribution Statement

Content in this chapter is adapted from: Page, C. (2021) Interculturalizing the Curriculum. Kwantlen Polytechnic University. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/interculturalizingcurriculum/

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Cultural sensitivity. In APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/cultural-sensitivity

Canadian Writing Centres Association. (2021). CWCA/ACCR Position Statement on Writing Centres in Canada. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zNMRc0kgBA_1bcEvBYCQdMtWhfzh02SA/view

Choudhury, S. (2021). Deep diversity: A compassionate, scientific approach to achieving racial justice.

Singh, A. A. (2019). The racial healing handbook: Practical activities to help you challenge privilege, confront systemic racism, and engage in collective healing. New Harbinger Publications.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

Wheaton College Massachusetts. (2021). Becoming an anti-racist educator. https://wheatoncollege.edu/academics/special-projects-initiatives/center-for-collaborative-teaching-and-learning/anti-racist-educator/