So, what is critical realism?

Brad C. Anderson

Let’s first distinguish the difference between the natural world and the social world. The natural world includes all the things in the universe, including stars, planets, gravity, and atoms.

The social world is the world of human activity, and it includes things like teachers, students, money, and national borders. A critical difference between the two is the social world requires human action to exist. If all of humanity vanished tomorrow, stars and planets would still exist, but teachers and money would not.

The social world is socially constructed.

Society is socially constructed. Money is not a product of nature–we invented it. Same with lawyers, newspapers, and schools. When we set up these systems, we establish rules of who can do what. Take teacher-student relations, for example. Society has agreed that teachers have the right to set assignments that you will lose sleep trying to finish, yet cannot ask you to take fifteen minutes out of your day to pick up their dry cleaning.

Social systems resist change.

Since human activity created things like teachers and students, you would think it would be easy to change the social world. If humans created the roles of teachers and students, and you are a human, then it should be a simple process for you to change the roles of teachers and students. Maybe you could change the system so you can tell the teacher what to do for a change.

Yet, these roles are resistant to change. Humans created these roles, but once set in place, some force protects them from change. Sure, people could alter these roles, but doing so across society would be extremely hard.

These systems impact us whether or not we are aware of them.

Most people never consciously think about why some people get to do some things but not others. Have you ever consciously considered why teachers can design your exam, but a lawyer cannot? Yet, even though we do not consciously contemplate these issues, we still unconsciously abide by society’s systems.

Even when we are unaware of the social structures that constitute human activity, these structures still have the power to enable or constrain the actions we can take. These structures have power over us, even if we are ignorant of their presence or nature.

Social systems are quasi-permanent

Furthermore, the nature of teacher-student relations existed long before you first walked into a classroom. They will likely persist long after you step into a class for the last time. Thus, even though these social structures exist only in humans’ minds, they possess a quasi-permanence separate from any one individual.

In total, once these social structures are created, they resist change. They have the power to enable or constrain your actions regardless of whether you are consciously aware of them, and they are semi-permanent.[1] Not bad for figments of our imagination.

Layers of Social Reality

To explain the observations described in the previous section, Roy Bhaskar developed the philosophy of critical realism. He described social reality as having three layers.[2]

- The real domain

- The actual domain

- The empirical domain

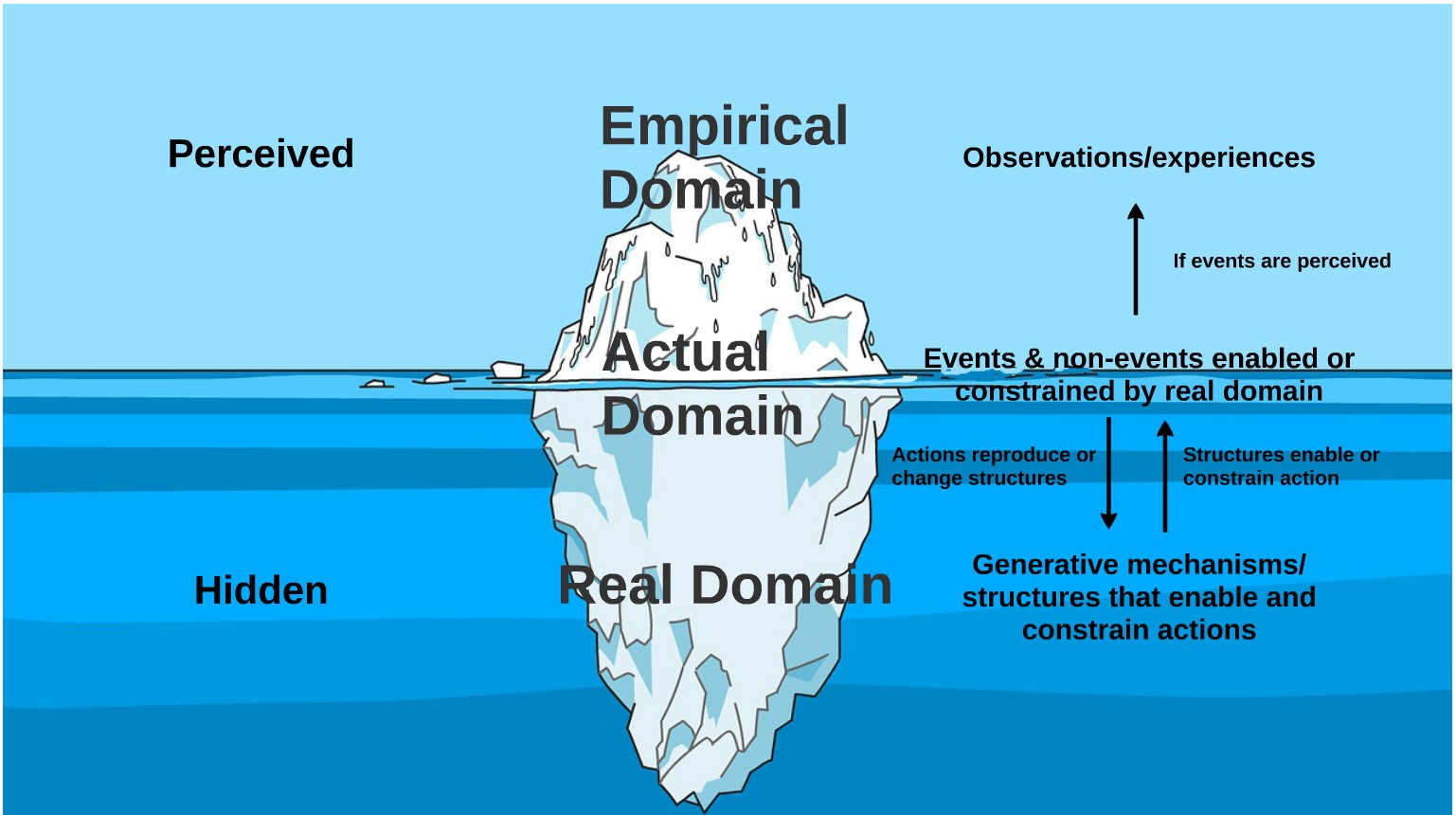

The following figure depicts the relationship between these three layers, after which the subsequent sections describe these layers in detail.

In brief, the real domain contains social structures and generative mechanisms (we’ll discuss what those are in a moment). These structures distribute resources and authority to different people within a social setting, which, in turn, enables or constrains the actions they can take.

These actions (or lack of action) create events (or non-events) in the actual domain. The actions people take tend to either reproduce structures back in the real domain or change those structures.

Sometimes an event happens, and no one notices. If an event is observed, however, that observation/experience occurs in the empirical domain. Let’s dig into the details of these layers and flesh them out.

Key Takeaways

Critical realism envisions three layers of social reality.

- The real domain

- The actual domain

- The empirical domain

- Ackroyd, S., & Fleetwood, S. (2000). Realism in Contemporary Organisation and Management Studies. In S. Ackroyd & S. Fleetwood (Eds.), Realist Perspectives on Management and Organisations (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Routledge. ↵

- Bhaskar, R. (1978). A Realist Theory of Science. New York, NY: Harvester Press. ↵