The Pictorial Evidence

Jessica Hemming

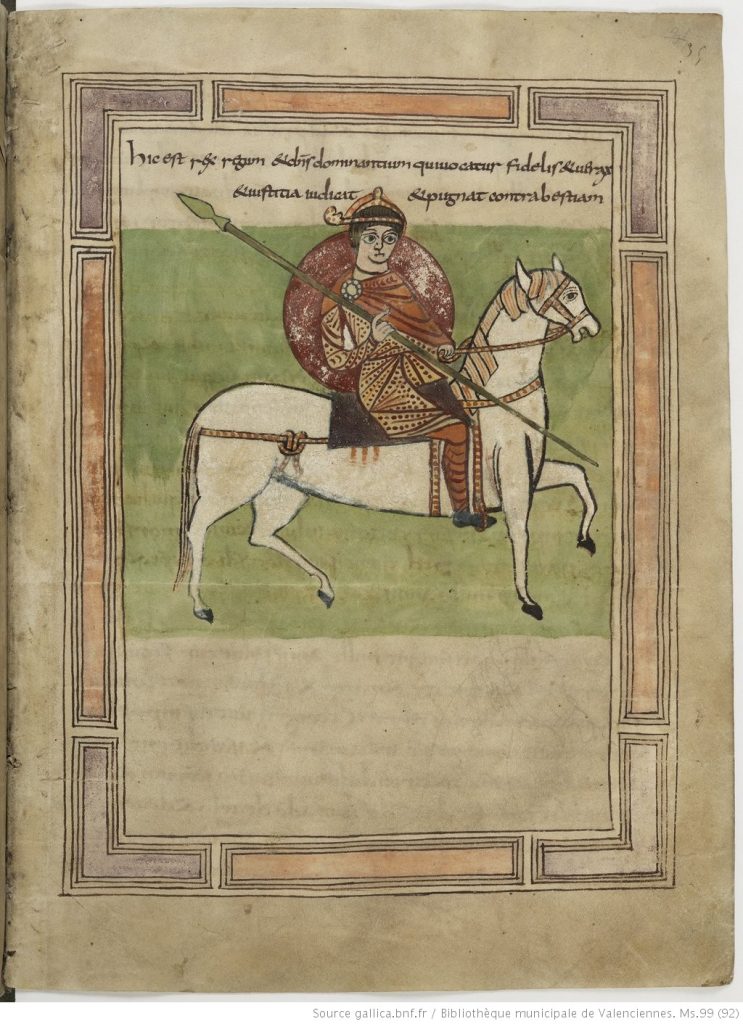

To return to the question of stirrup diffusion in Western and Central Europe, another type of source that can shed some light on the matter is visual art—especially in illuminated (illustrated) manuscripts. Unfortunately, there is no securely-dated artistic evidence for stirrups in manuscripts before the early 9th century. One of the earliest sources is the Apocalypse of Valenciennes, a Carolingian religious manuscript of c.800-825, which shows an exceptionally clear mounted spearman using stirrups:

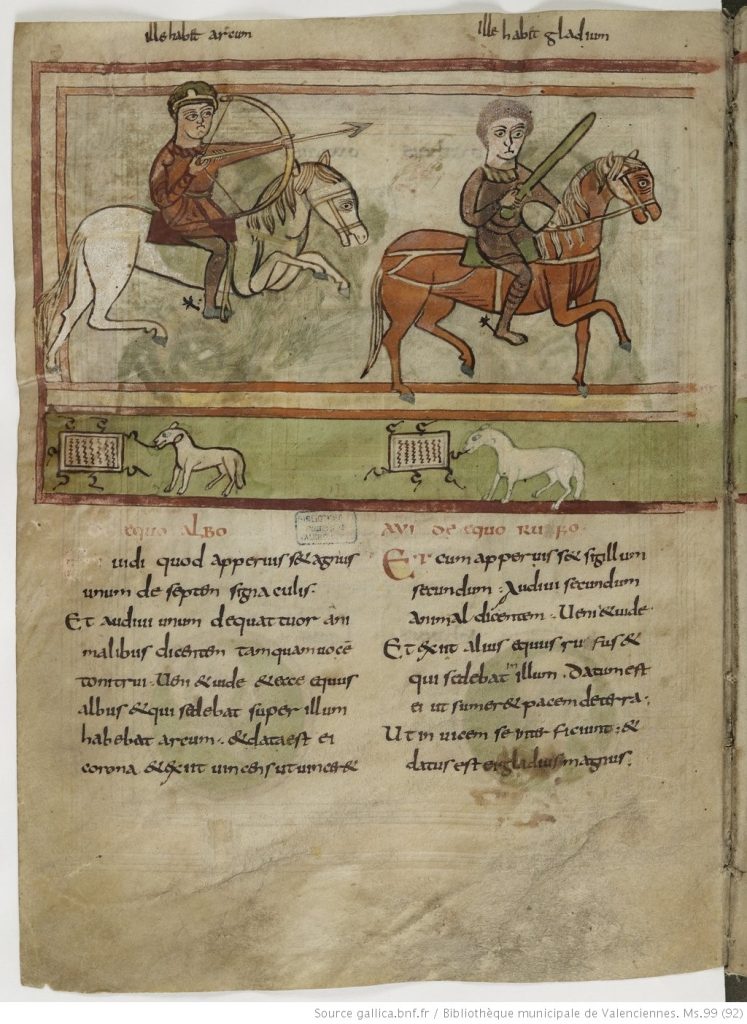

On another page we find two of the biblical “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” riding with stirrups and two without. This is intriguing, to say the least. On folio 12 verso[1] two of the apocalyptic riders appear with labels over their heads pointing out that one is an archer and one a swordsman; only the archer has stirrups. Given that the steppe peoples who used stirrups routinely were also famous for their mounted archery skills, could this be a visual allusion to an Avar or Bulgar horseman?

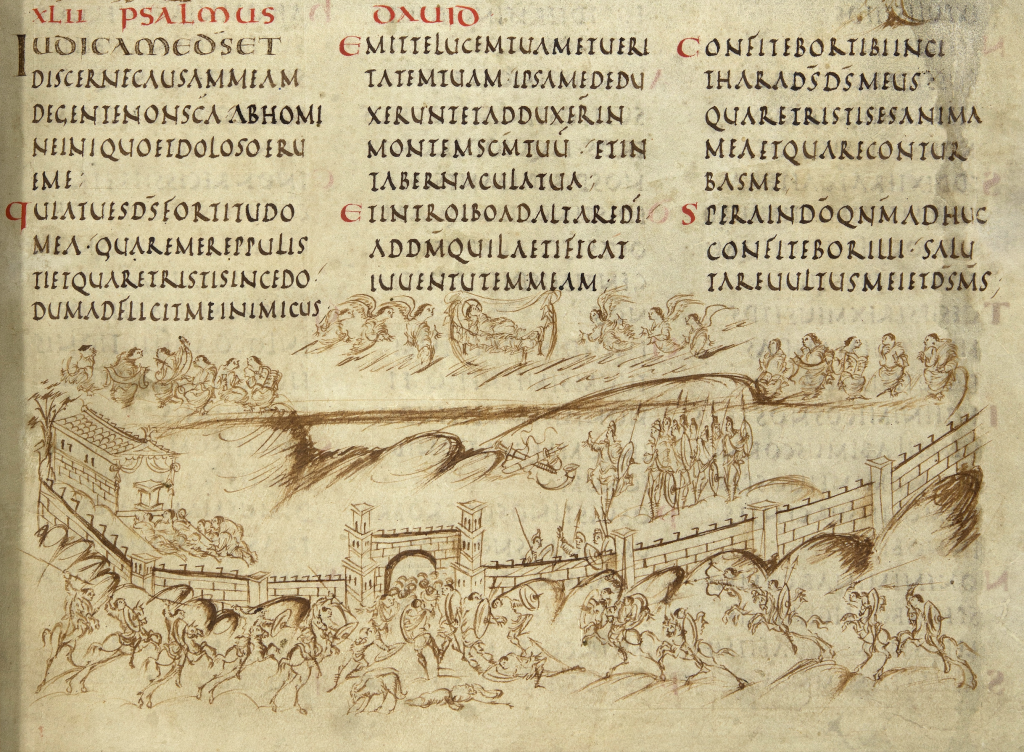

Two famous Carolingian psalters (books of Psalms) of this same century offer suggestive contrasts. The earlier one, dated c.820-845, is the astonishing Utrecht Psalter, now fully digitized and annotated here on the internet.[2] It contains 166 pen-and-ink drawings of extraordinary energy and dynamism. Among these are numerous depictions of armed horsemen—none of whom appear to be using stirrups. Some scholars claim to see an Avar warrior with a characteristic reflex (double-curved) bow and stirrups in one of the pictures (folio 25r).[3]

The slightly later Carolingian Golden Psalter (c.883-900) from the monastery of St Gall in Switzerland, by contrast, features plenty of stirrups, although not every horseman depicted has them. This is perhaps in itself significant.

What does this pictorial evidence tell us? It only proves that some Carolingian manuscript artists (who were generally monks) were familiar with stirrups by the early 800s at latest. It suggests that some Carolingian cavalrymen were actually using stirrups during this time, but that their distribution was uneven enough that illuminators were only including them sporadically, even within a single book. Although stirrups do make more frequent appearances in Western European art as time goes on, it has been pointed out more than once that on the Bayeux Tapestry (c.1080), not all the Norman horsemen are using them. We will return to this significant artefact in the section discussing the technical advantages of stirrups in warfare.

By the late 11th century, the stirrup begins to feature in Western European literature. The famous Old French martial epic known as The Song of Roland, which was written down in its current form c.1080, includes the words estrief or estrieu“stirrup,” derived from that same Germanic “climbing rope” word (in this case Frankish *streup). By the end of that century, it seems likely that stirrups were quite widespread in Central and Western Europe; representations of 12th-century horsemen typically all show them using stirrups.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Pamela Kyle Crossley at Dartmouth College and Rob Webley at the University of Exeter Warhorse project for discussing some of the finer details of stirrup distribution and use with me. Professor Crossley’s expertise in the history of Eurasian steppe societies and of horsemanship clarified some especially complex issues.

Media Attributions

- Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque de Valenciennes 35r is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque de Valenciennes 12v is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Utrecht Psalter 24v is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Carolingian Psalter is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- When talking about manuscripts, recto means the front side of a page (folio) of vellum, while verso means the back side of that same page. These are abbreviated like this: folio 14r, folio 14v. ↵

- Utrecht Psalter on University of Utrecht Library website: https://bc.library.uu.nl/utrecht-psalter.html. ↵

- Pohl, The Avars, 377. The bow is indeed very clear, but the stirrups are invisible to most observers. You can try for yourself using the zoom-in function on the website. ↵