Images of Muhammad

Niall Christie

From as far back as we can trace, Islam has had a mixed relationship with depictions of living things, and of the Prophet in particular, in art. The Qur’an was revealed in a region where the religion of the majority of the people was paganism, characterised in particular by frequent idol worship. The holy text, not surprisingly, repeatedly and emphatically opposes this practice, but at the same time, it contains no explicit prohibition of the depiction of living things by humans. The hadith include some stories that seem to prohibit depictions of this type, but there has been debate about to what extent they should be seen as universally applicable. The end result is that Muslim attitudes to images of living things, including the Prophet, have been, and continue to be, variable depending on the temporal, geographical and cultural context.

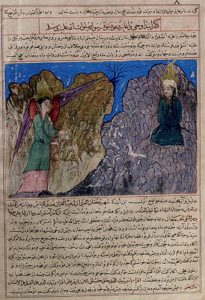

At times Muslim depictions of the Prophet demonstrate no qualms at all, resulting in pieces like the 15th-century image to the right, in which we see the first revelation being made by the angel Gabriel to the Prophet.

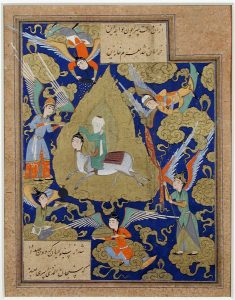

Other works demonstrate more reluctance to provide a full depiction of Muhammad, and one of the methods that artists have used is to veil his face, as in the example below of Muhammad’s ascension[1]. Note that the angels accompanying the Prophet are not veiled, so the artist is not simply avoiding depicting the faces of living things as a whole here, but is only doing so with the figure of Muhammad. The fact that the Prophet is veiled can also be interpreted as having the effect of turning him into an “everyman” figure, someone whom Muslims can seek to emulate in their own practice of their faith.

Yet despite the fact that depictions of the Prophet, and other living creatures, can be found widespread throughout Islamic art, one thing that is striking is that one generally does not see such depictions in explicitly religious contexts such as mosques (the major exception are vegetal motifs, representing Paradise), and there are also very few Muslim pictorial depictions of God. Such avoidance reflects Muslims’ desire to avoid idolatry, even if it might be accidental, as well as a desire to render suitable respect to God and the Prophet.

This brings us, of course, to the question of controversies surrounding depictions of Muhammad in modern media such as the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten (in 2005) or the French magazine Charlie Hebdo (in 2011 and 2012). While undoubtedly some of the protestors who took part in the demonstrations that followed the publication of these were motivated by a sense of offense at the act of depicting Muhammad, what was much more offensive to the protestors was the fact that these depictions were clearly meant to be insulting (something that was exacerbated, in the first case, by the fact that in 2003 Jyllands-Posten had refused to publish a cartoon of Jesus on the grounds that Christians might be offended). It is also undeniable that some Muslim extremists took the controversies as an opportunity to incite protests to become more violent or to claim that their terrorist acts were enacted in response to the events. The Charlie-Hebdo attack of January 2015 is one example of this, and was condemned by Muslims across the globe.

Media Attributions

- Muhammad Majmac al tawarikh is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The Mi‘raj © thesandiegomuseumofartcollection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ascension. According to Muslim tradition, during one night early on in his mission, before the hijra, Muhammad travelled to Jerusalem and then ascended to Paradise, where he met God and some of the prophets who had come before him. ↵

political, earthly affairs, as opposed to spiritual

through pictures