Consolidation

Barrie Brill

From the 730s, it can be said that Charles occupied a ‘vice-regal’ position that was widely recognized, albeit still unsanctioned. Nonetheless, he still had to consolidate Frankish power in the newly conquered territories, particularly in the north and east. This led him actively to support the evangelization policy carried out in the regions by Anglo-Saxon missionaries.

The Extension of Frankish Rule in Frisia and Germany

The succession crisis of 714 had revealed the extent of the danger that threats from the peripheral areas could pose for the Franks. The Frisians, Saxons, and Aquitainians had taken advantage of the disarray to launch pillaging raids especially against Austrasia. All Charles’ work north and east of the Rhine seems to have been part of a project to create a barrier dedicated to protecting the kingdom. He defended vulnerable borders by erecting new fortresses such as that of Christenberg near Marburg. He encouraged colonization by those Austrasians who later would be called orientales Franci (eastern Franks) of the region of the lower and middle valleys of the Main that was well on the way of becoming Franconia. This provided a route to the east and also provided more convenient access to the southern duchies of Bavaria and Alemannia.

In Frisia, Charles broke with the policies of his predecessors since he understood that, to definitively integrate western Frisia, it would be necessary to attack the centre of Frisian resistance east of the Rhine. To accomplish this, he mounted a naval expedition, utilizing the services of the Frisians who had already submitted to his authority, and succeeded in controlling the whole of Frisia after 734.

Against the Saxons, Charles did not have the means to act directly, but he organized a protective barrier in middle Germany, reinforcing the Frankish colonization along the lower and middle Main valley. This afforded some protection against the Saxons. This policy that sought to control the territories east of the Rhine by military means was completed by the support that Charles provided to the Anglo-Saxon missionaries who were undertaking to evangelize the region.

Support for Willibrord and Boniface’s Mission

Frisia and Alemannia were favoured regions of Anglo-Saxon missionaries in the eighth century. Willibrord, a missionary monk from England, settled at Utrecht, which was a Frankish advance post in contact with the Frisians. The Frisians were pagans and were hostile to Christianity. The military campaigns of Pippin had opened the region to missionaries and the installation of churches. Willibrord was anxious to have his activities approved by the papacy and travelled to Rome in 695. At the time of this visit, he was consecrated Bishop of the Frisians. His mission now had a national or ethnic framework recognized by the Church. He also had need of the resources and the support offered by the Austrasian mayor of the palace and his family. In 697-698, they had donated the land for a family monastery that was established at Echternach and was devoted to the education of missionary monks. The undertaking was so political that the death of Pippin, in 714, was followed by a general uprising in Frisia and a temporary return to paganism. Charles Martel, like his father, pursued the same ends, and he inflicted a major military defeat on the Frisians and supported Willibrord and his disciples.

Another missionary, Winfrid, had remained a monk in Wessex until he was about forty. He had entered the monastery of Nursling as an oblate and received an excellent education from various scholars including the grammarian Aldhelm. Winfrid became a teacher in the monastic school and gained a reputation as a scholar. He was elected abbot of Nursling in 717, an office that he quickly gave up in order to devote himself to the conversion of his Saxon brethren who had remained on the continent and who were still pagan. He visited Willibrord in 716 and again in 719. He took the model of Willibrord to heart and like him only envisaged his missionary activity in close relation with the pope. Winfrid landed in Friesland, but went to Rome in order to seek the support of Pope Gregory II. On May 15, 719, the pope recognized Winfrid as his representative and gives him the name of Boniface as a sign of the link that united him to the Roman see. Boniface began to work in the central Germanic territories and then returned to Rome in 722, where he was ordained bishop without a fixed see. He then sought the official support of the mayor of the palace, who granted him without any restriction the possibility of using all the administrative and military structures set up by the Franks. His continuous success as a missionary led Pope Gregory II in 732 to give Boniface the pallium thus making Boniface an archbishop with authority throughout Germany.

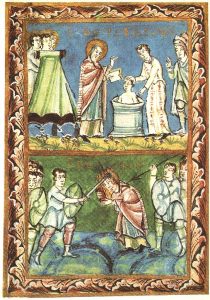

With all these supports, Boniface set up the first ecclesiastical network in the central and southern Germanic territories. In Wurzburg, the former political centre of the dukes of Thuringia, Boniface founded the first episcopal seat of the region in 741, based on the heritage of the Irish missionary Kilian (d. 690), and he considered the region sufficiently Christianized to implant there three monastic communities of Anglo-Saxon nuns. These ecclesiastical structures supported the Frankish colonization movement in the Upper Main Valley. Further north, where he himself felled the sacred oak dedicated to Thor near Geismar, he founded two dioceses, Erfurt and Büraburg, whose existence was constantly threatened by the Saxon raids. In 744, he founded the monastery that was destined to become the great centre of missionary activity in Saxony: Fulda. Here he promoted the rule of Saint Benedict. Boniface went on to reorganize the church in Bavaria with the consent of Duke Odilo. He continued his missionary activity and would die a martyr in an ambush in Dokkum in June 754 in Frisia, where he had begun his missionary activity decades before. His body was buried at Fulda. While these territories beyond the Rhine were difficult to control, they were always part of a zone of influence of the Austrasians in general and the Pippinids in particular.

Questions for Consideration

- In what ways did Charles’ alliance with the Anglo-Saxon missionaries serve to strengthen his control throughout the region?

- What challenges remained for Charles’ successors?

Media Attributions

- St. Boniface Baptising and Martyrdom in 754 is licensed under a Public Domain license

A person who has dedicated themselves to the service of God, but who has not yet taken formal vows

the seat of power and jurisdiction for a bishop

OED: A woollen vestment conferred by the Pope on archbishops in the Latin Church