What Muslims Believe

Niall Christie

The Qur’an:

The first source of Muslim belief is the Qur’an, which is regarded by Muslims as the very word of God, transmitted to humanity through His Prophet. It is seen as the final, perfect version of the revelation that was previously made humans, who misunderstood or distorted its teachings on earlier occasions. The book itself is roughly the size of the New Testament, and deals with a number of themes:

- God: We are told about the nature of God. He is omnipotent and omniscient, but also kind and benevolent to humanity. Most importantly, God is one single being, with no partners, associates, or offspring. Idolatry is thus fiercely opposed. Meanwhile Christians and Jews are also criticised for associating other figures with God. In particular, the Christian claim that Jesus is the son of God, and also God, is explicitly refuted; indeed, in the text Jesus himself is described as denying the truth of such a claim.

- Stories of the Prophets: The Qur’an also recounts or alludes to stories of the prophets, most of whom would be recognised by readers of Bible. In the Muslim view, the first prophet was Adam, and then God communicated with many subsequent figures such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus; the latter was the precursor to Muhammad, the very last and Seal of the Prophets. Of these figures, Abraham, Moses, David, and Jesus were given scriptures to share with humanity, but as noted above, humans misunderstood or distorted these revelations, making the new revelation to Muhammad necessary.

- Legal Teaching: The text describes or at least alludes to a range of legal teachings, making it a social contract as well as a book of religious doctrine. Thus one may consult the Qur’an to establish how to divide up inheritance, how to treat the women in the community, how to look after the poor, the correct manner in which to undertake warfare, and how to deal with non-Muslims. Not all the teachings in the text are clearly stated, however, and as time went on the Muslims periodically encountered situations where Qur’anic teaching could not be applied easily, and so legal scholars used hadith material (see above) and further legal argumentation to develop the Qur’an’s teachings into a full-blown legal code known as the shari‘a.

- The Day of Judgment: The Qur’an tells us that we will all die at the times appointed for us. Then, at time known only to God, we will all be resurrected and judged according to our deeds, finding our way to Paradise or Hell as appropriate. Both these places are described in great detail in the Qur’an; Paradise is a garden, with trees and rivers, where food and drink are plentiful, there are gems and gold, and (depending on the translation) beautiful maidens who will be heavenly wives for the pious. Hell is a place of burning fires and eternal torment.

The “Pillars of Islam”:

To avoid Hell and gain a place in Paradise, Muslims are expected to believe in God and His scripture, and to express that belief through their actions, obeying Islamic legal teaching and seeking to do good. As part of this, Muslim daily life is regulated through five practices commonly known as the “Pillars of Islam”. These are as follows:

- Shahada (profession of faith): Muslims testify to the truth of their faith through two statements: There is no god except God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God. These statements are made frequently in Muslim ritual practices, such as during salat, below.

- Salat (ritual prayer): Most Muslims conduct ritual prayer five times a day, at dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset and later in the evening. The ritual prayer consists of a set of standard invocations and recitations, accompanied by changes of bodily posture, from standing, to bowing, to kneeling, to prostrating oneself before God; the number of times that one does this depends on the time of prayer. Salat can be performed anywhere, but if possible it should be conducted facing Mecca. A mosque is a place set aside for prayer, and Muslims are particularly encouraged to join their fellows in the mosque for Friday noon prayers, when they will also hear a sermon. Muslims do, of course, also conduct informal personal prayer in addition to the formal salat ritual.

- Zakat (almsgiving): Muslims are expected to donate a portion of their wealth to charity every year.

- Sawm (fasting): During the month of Ramadan, Muslims fast from dawn until dusk, abstaining from food, drink, smoking and sexual activity. Not all are required to fast: pregnant or nursing women, pre-pubescent children, the sick, the infirm, and travellers are either exempted or required to make up the fast later on. This practice is undertaken to commemorate the first revelation to Muhammad, and is seen by many Muslims as an opportunity to refocus their attention on their faith.

- Hajj (greater pilgrimage): Once during their lifetime, if they are able, every Muslim should perform the greater pilgrimage to Mecca. This takes place at a set time of the year, in the Muslim month of Dhu’l-Hijja. The hajj involves a number of rituals, including visiting a number of sites in and around Mecca, and engaging in activities such as walking around the Ka‘ba and throwing stones at pillars representing Satan.

- See A step-by-step guide to the hajj from AlJazeera.

- Watch Seven things you don’t know about the hajj from the BBC.

Jihad:

Jihad is a concept that is often misunderstood in the modern day. At the basic level, the word means “striving”. In Muslim teaching, the term is associated with any sort of struggle for the faith. In times of war this can be a military struggle, though such activity must be conducted within a number of restrictions, including not harming non-combatants (Muslim or non-Muslim), not engaging in wanton destruction of property, and not deliberately killing oneself on the battlefield. However, Muslims see the military aspect of jihad as but one part of a much wider concept. One can also wage jihad by speaking out for social justice, for example. From the earliest days, the concept was also understood to encompass the inner struggle that one wages against one’s own inner sinfulness, and by about the 12th century Muslim religious scholars, especially those influenced by mystical ideas, had elaborated a theory of jihad that saw this inner struggle as the most important, and a prerequisite for going out to wage the external struggle. Thus the concept of jihad is a rather more complex one than some media outlets or extremists would have us believe.

Interfaith Relations:

Since the earliest days of the faith, Christians and Jews were allowed to live in Muslim communities, provided that they paid poll tax, accepted Muslim authority, and did not cause trouble. Over time this usage became extended to other non-Muslims as the Muslim world expanded. Islamic law does contain certain social restrictions that may be placed on non-Muslims if the ruler chooses, but many rulers kept these to minimum or chose not to impose them, with the result that at times non-Muslims rose to positions of prominence within Muslim states. There were exceptions, of course, of whom one of the most notorious was the Egyptian caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (r. 996-1021), who persecuted Christians and attained particular notoriety in 1009 when he ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. However, in both the middle ages and the modern day there were plenty of cases of co-operation and co-existence between Muslims and non-Muslims, even in face of opposition from Muslim authorities; one of the most striking recent examples occurred during the Egyptian revolution of 2011, when Christian and Muslim protestors co-operated closely with each other to advance their shared goal of regime change.

Media Attributions

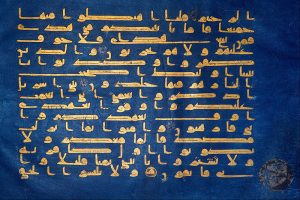

- Blue Qur’an Page

- 2014 Eid ul-Fitr Praying – Imam Ali Shrine – Najaf 4 © Sonia Sevilla is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Egyptian Unity © Gigi Ibrahim is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Arabic masjid, lit. “a place of prostration”

deliberately cruel