Muhammad and the Origins of Islam

Niall Christie

According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Muhammad was born in about 570 in the Arabian city of Mecca. At the time Mecca was an important trade and pagan pilgrimage centre, and like much of Arabia its society was arranged along tribal lines. Muhammad’s start in this environment was not auspicious, for his father had died before he was born, and his mother also died when he was very young. However, he was able to make his way in society, following his father’s trade as a merchant and establishing a reputation for trustworthiness. He attracted the attention of a wealthy widow named Khadija, becoming her business manager, and then her husband. The two loved each other deeply, and while she was alive Muhammad took no other wives, something that was unusual in the society of the time.

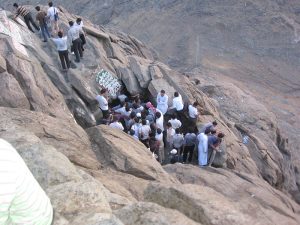

Muhammad was dissatisfied with the pagan beliefs followed by most of the Meccans, and he took to meditating in the mountains outside the city, seeking a deeper spirituality and relationship to the divine. It was during one of these retreats, on 27 Ramadan 610, that he was approached by the angel Gabriel, who revealed to him the first verses of the Qur’an, the Muslim holy book, initiating what would be an ongoing series of revelations that would take place during the rest of Muhammad’s lifetime. These revelations called humans to reject idol-worship and to return to good behaviour and the worship of the one true God, the same deity followed by the Christians and the Jews. Muhammad had been appointed by God as Rasul Allah, and it was now his duty to bring God’s message to humanity.

The Prophet began preaching the following year, attracting converts from his own household (starting with Khadija) and others. However, he also encountered opposition from the leaders in Mecca, as his message opposed the dominant pagan faith and thus threatened the wealth that visits from pilgrims brought into the city. As the Prophet, he also became the de facto leader of the new Muslim community, which threatened the authority of the traditional tribal leaders of the city. Muslims began suffering from verbal and physical attacks, and the situation came to a head in 619, when both Khadija and Abu Talib, Muhammad’s uncle and principal protector, died. Muhammad began seeking support outside Mecca, and in 622 he and his followers emigrated to the oasis of Yathrib, some 200 miles to the north, after he was invited to help the community there resolve a bitter feud between two tribes that was tearing it apart. This emigration is known in Arabic as the hijra, and is the event from which Muslims date their calendar.[1] Most of the Yathribis converted to Islam, although there were also a number of Jewish tribes who maintained their faith. Yathrib became known as Madinat al-Nabi, often shortened to al-Madina, and rendered as Medina in English.

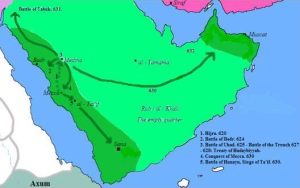

Circumstances drove Muhammad into a war with Mecca. If Islam was ever to become more than a local cult, he would need the expertise of the Meccans, and Medina also needed to be economically independent, which meant securing resources controlled by Mecca. Muhammad justified the war because the Meccans had opposed Islam, persecuted its followers, and were preventing others from practicing the faith. Over the course of eight years, during which there were three major battles and a number of raids and skirmishes, he fought the Meccans to a standstill and eventually managed to take over the city itself in 630. The Ka‘ba, a cuboid building in the central sacred area of the city that the Meccans had used as a pagan shrine, was confirmed as the most important holy site in Islam, constructed by Abraham and his son Ishmael, the ancestor of the Arabs.

During this period Muhammad also had to deal with opposition from three of the Jewish tribes of Medina, who were exiled or, in the case of the third tribe, enslaved and executed. This has been seen by some modern commentators as the origin of Muslim-Jewish hostility, but such a view misunderstands the circumstances. The problem at the time was not the Jews’ religion (even though they did not accept the Prophet’s message), but rather the fact that they had behaved treacherously and broken agreements, and in the process were also undermining Muhammad’s ability to spread Islam; arguably, by the customs of the time, the first two tribes got off lightly. Modern hostility between Muslims and Jews has much more to do with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than events in the 7th century, despite the efforts of some to claim the existence of a historic antipathy.

Over the last two years of his life, Muhammad extended Islam’s influence over the rest of the Arabian Peninsula. This was achieved mostly through diplomacy, and most of the time the Prophet received delegations from the various tribes of the region. Christians and Jews, seen as earlier recipients of the divine revelation, were allowed to keep their faith provided that they accepted Muslim authority and paid a poll tax. Pagans were required to convert to Islam. By the time that he died on 8 June 632, Muhammad and Islam’s authority were acknowledged in most of Arabia. It would be left to his successors to take the message further.

Media Attributions

- Map of Arabia 600 AD © Slackerlawstudent is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Entrance of Hira cave © Mardetanha is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Kaaba 111 © Tahir mq is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Muslim Conquest 2 © Javierfv1212 adapted by Snitty is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Muslims use a lunar calendar of 12 months. Thus the Muslim year is shorter than the solar year, and festivals and holy days move as the years pass. ↵

Religions with beliefs that do not involve strict principles, such as monotheism, which is central to Christian and Islamic thought. They tend to involve nature spirits, polytheistic beliefs, and be more flexible in their customs and ideas.

Also sometimes rendered in English as “Koran.” Arabic: “recitation.”

Arabic: “the Messenger of God”. “Allah” is the Arabic equivalent of the English “God”.

Arabic: “the city of the Prophet”.

Arabic: "the city"

shaped similar to a cube

a feeling of hared or animosity