Chapter 6: Marketing Research

6.2 Marketing Research, Intelligence and Ethics

Learning Objectives

- Learn how marketing intelligence differs from marketing.

- Describe the limitations of market intelligence and its ethical boundaries.

- Explain when marketing research should and should not be used.

A certain amount of marketing information is being gathered all the time by companies as they engage in their daily operations. When a sale is made and recorded, this is marketing information that’s being gathered. When a sales representative records the shipping preferences of a customer in a firm’s customer relationship management system, this is also marketing information that’s being collected. When a firm gets a customer complaint and records it, this too is information that should be put to use. All these data can be used to generate consumer insight. However, truly understanding customers involves not just collecting quantitative data (numbers) related to them but qualitative data, such as comments about what they think.

Internally Generated Data and Reports

As we explained, an organization generates and records a lot of information as part of its daily business operations, including sales and accounting data and data on inventory levels, back orders, customer returns, and complaints. Firms are also constantly gathering information related to their websites, such as data generated about the number of people who visit a website and its various pages, how much time they spend there, and what they buy or don’t buy. Companies use these data in all kinds of ways. They use them to monitor the overall visitor traffic a site gets, to see which areas of the site people aren’t visiting and why, and to automatically offer visitors products and promotions by virtue of their browsing patterns.

Watch a fascinating documentary about how Walmart, the world’s most powerful retailer, operates.

Analytics Software

Increasingly, companies are purchasing analytics software to help them collect and make sense of internally generated information. Analytics software allows managers who are not computer experts to gather all kinds of different information from a company’s databases—information not produced in reports regularly generated by the company. The software incorporates regression models, linear programming, and other statistical methods to help managers answer “what if” types of questions. For example, “If we spend 10 percent more of our advertising on TV ads instead of magazine ads, what effect will it have on sales?”

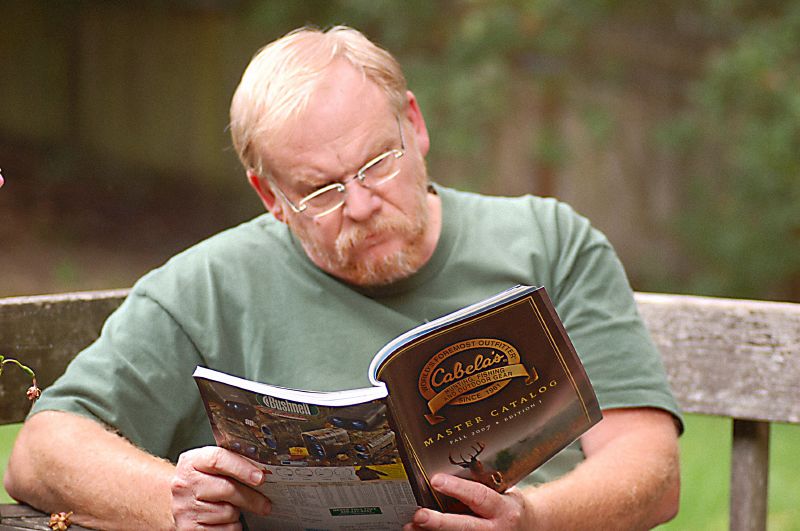

The camping, hunting, fishing, and hiking retailer Cabela’s has managed to refine its marketing efforts considerably using analytics software developed by the software maker SAS. “Our statisticians in the past spent 75 percent of their time just trying to manage data. Now they have more time for analyzing the data with SAS, and we have become more flexible in the marketplace,” says Corey Bergstrom, director of marketing research and analysis for Cabela’s. “That is just priceless” (Zarello, 2009).[1]

The company uses the software to analyze sales transactions, market research, and demographic data associated with its large database of customers. It combines the information with web browsing data to gain a better understanding of individual customers’ marketing channel preferences as well as other marketing decisions. For example, does the customer prefer Cabela’s one-hundred-page catalogues or the seventeen-hundred-page catalogues? The software has helped Cabela’s employees understand these relationships and make high-impact data-driven marketing decisions (Zarello, 2009).[2]

Market Intelligence

A good internal reporting system can tell a manager what happened inside his firm. But what about what’s going on outside the firm? What is the business environment like? Are credit-lending terms loose or tight, and how will they affect what you and your customers are able to buy or not buy? How will rising fuel prices and alternate energy sources affect your firm and your products? Do changes such as these present business obstacles or opportunities? Moreover, what are your competitors up to?

Not gathering market intelligence leaves a company vulnerable. Remember Encyclopedia Britannica, the market leader in print encyclopedia business for literally centuries? Encyclopedia Britannica didn’t see the digital age coming and nearly went out of business as a result (suffice it to say, you can now access Encyclopedia Britannica online). By contrast, when fuel prices hit an all-time high in 2008, unlike other passenger airline companies, Southwest Airlines was prepared. Southwest had anticipated the problem and early on locked in contracts to buy fuel for its planes at much lower prices. Other airlines weren’t as prepared and lost money because their fuel expenses skyrocketed. Meanwhile, Southwest Airlines managed to eke out a profit. Collecting market intelligence can also help a company generate ideas or product concepts that can then be tested by conducting market research.

Gathering market intelligence involves a number of activities, including scanning newspapers, trade magazines, and economic data produced by the government to find out about trends and what the competition is doing. In big companies, personnel in a firm’s marketing department are primarily responsible for their firm’s market intelligence and making sure it gets conveyed to decision makers. Some companies subscribe to news service companies that regularly provide them with this information. LexisNexis is one such company. It provides companies with news about business and legal developments that could affect their operations. Other companies subscribe to mystery shopping services, companies that shop with a client and/or competitors and report on service practices and service performance. Let’s now examine some of the sources of information you can look at to gather market intelligence.

Search Engines and Corporate Websites

An obvious way to gain market intelligence is by examining your competitors’ websites as well as doing basic searches with search engines like Google. If you want to find out what the press is writing about your company, your competitors, or any other topic you’re interested in, you can sign up to receive free alerts via e-mail by going to Google Alerts. Suppose you want to monitor what people are saying about you or your company on blogs, the comment areas of websites, and social networks such as Facebook and Twitter. You can do so by going to a site like WhosTalkin.com, typing a topic or company name into the search bar, and voilà! All the good (and bad) things people have remarked about the company or topic turn up. What a great way to seek out the shortcomings of your competitors. It’s also a good way to spot talent. For example, designers are using search engines like WhosTalkin.com to search the blogs of children and teens who are “fashion forward” and then involving them in designing new products.

WhosTalkin.com and Radian6 (a similar company) also provide companies with sentiment analysis. Sentiment analysis is a method of examining content in blogs, tweets, and other online media (other than news media) such as Facebook posts to determine what people are thinking at any given time. Some companies use sentiment analysis to determine how the market is reacting to a new product. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) uses sentiment analysis to track the progress of flus; as people post or tweet on how sick they are, the CDC can determine where a flu is increasing or decreasing.

Publications

The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Fortune, BusinessWeek, the McKinsey Report, Sales and Marketing Management, and the Financial Times are good publications to read to learn about general business trends. All of them discuss current trends, regulations, and consumer issues that are relevant for organizations doing business in the domestic and global marketplace. All these publications are online as well, though you might have to pay a subscription fee to look at some of their content. If your firm is operating in a global market, you might be interested to know that some of these publications have Asian, European, and Middle Eastern editions.

Other publications provide information about marketplace trends and activities in specific industries. Consumer Goods and Technology provides information that consumer packaged-goods firms want to know. Likewise, Progressive Grocer provides information on issues important to grocery stores. Information Week provides information relevant to people and businesses working in the area of technology. World Trade provides information about issues relevant to organizations shipping and receiving goods from other countries. Innovation: America’s Journal of Technology Commercialization provides information about innovative products that are about to hit the marketplace.

Trade Shows and Associations

Trade shows are another way companies learn about what their competitors are doing (if you are a marketing professional working a trade show for your company, you will want to visit all your competitors’ booths and see what they have to offer relative to what you have to offer). And, of course, every field has a trade association that collects and disseminates information about trends, breakthroughs, new technology, new processes, and challenges in that particular industry. The American Marketing Association, Food Marketing Institute, Outdoor Industry Association, Semiconductor Industry Association, Trade Promotion Management Association, and Travel Industry Association provide their member companies with a wealth of information and often deliver them daily updates on industry happenings via e-mail.

Salespeople

A company’s salespeople provide a vital source of market intelligence. Suppose one of your products is selling poorly. Will you initially look to newspapers and magazines to figure out why? Will you consult a trade association? Probably not. You will first want to talk to your firm’s salespeople to get their “take” on the problem.

Salespeople are the eyes and ears of their organizations. Perhaps more than anyone else, they know how products are faring in the marketplace, what the competition is doing, and what customers are looking for.

A system for recording this information is crucial, which explains why so many companies have invested in customer relationship management systems. Some companies circulate lists so their employees have a better idea of the market intelligence they might be looking for. Textbook publishers are an example. They let their sales representatives know the types of books they want to publish and encourage their representatives to look for good potential textbook authors among the professors they sell to.

Suppliers and Industry Experts

Your suppliers can provide you with a wealth of information. Good suppliers know which companies are moving a lot of inventory, and oftentimes they have an idea why. In many instances, they will tell you if the information you’re looking for is general enough so they don’t have to divulge any information that’s confidential or that would be unethical to reveal—an issue we’ll talk more about later in the book. Befriending an expert in your industry, along with business journalists and writers, can be helpful, too. These people are often “in the know” because they get invited to review products (Gardner, 2009).[3]

Customers

Lastly, when it comes to market intelligence don’t neglect observing how customers are behaving. They can provide many clues, some of which you will be challenged to respond to. For example, during the latest economic downturn, many wholesalers and retailers noticed consumers began buying smaller amounts of goods—just what they needed to get by during the week. Seeing this trend, and realizing that they couldn’t pass along higher costs to customers (because of, say, higher fuel prices), a number of consumer-goods manufacturers slightly “shrank” their products rather than raising prices. You have perhaps noticed that some of the products you buy got smaller—but not cheaper.

Can Market Intelligence Be Taken Too Far?

Can market intelligence be taken too far? The answer is yes. In 2001, Procter & Gamble admitted it had engaged in “dumpster diving” by sifting through a competitor’s garbage to find out about its hair care products. Although the practice isn’t necessarily illegal, it cast P&G in a negative light. Likewise, British Airways received a lot of negative press in the 1990s after it came to light that the company had hacked into Virgin Atlantic Airways’ computer system (Miller, 2001).[4]

Gathering corporate information illegally or unethically is referred to as industrial espionage. Industrial espionage is not uncommon. Sometimes companies hire professional spies to gather information about their competitors and their trade secrets or even bug their phones. Former and current employees can also reveal a company’s trade secret either deliberately or unwittingly. Microsoft recently sued a former employee it believed had divulged trade secrets to its competitors (“Microsoft Suit,” 2009).[5] It’s been reported that for years professional spies bugged Air France’s first-class seats to listen in on executives’ conversations (Anderson, 1995).[6]

To learn more about the hazards of industrial espionage and how it’s done, check out video 6.5.

Video 6.5. Spying at Work: espionage, who, how, why, how to stop it. Ideas theft. Business Security Speaker by Futurist Keynote Speaker Patrick Dixon.

Marketing Research

Marketing research is what a company has to resort to if it can’t answer a question by using any of the types of information we have discussed so far—market intelligence, internal company data, or analytics software applied to data. As we have explained, marketing research is generally used to answer specific questions. The name you should give your new product is an example. Unless your company has previously done some specific research on product names—what consumers think of them, good or bad—you’re probably not going to find the answer to that question in your internal company data. Also, unlike internal data, which are generated on a regular basis, marketing research is not ongoing. Marketing research is done on an as-needed or project basis. If an organization decides that it needs to conduct marketing research, it can either conduct marketing research itself or hire a marketing research firm to do it.

So when exactly is marketing research needed? Keep in mind that marketing research can be expensive. You therefore have to weigh the costs of the research against the benefits. What questions will the research answer, and will knowing the answer result in the firm earning or saving more money than the research costs?

Marketing research can also take time. If a quick decision is needed for a pressing problem, it might not be possible to do the research. Lastly, sometimes the answer is obvious, so there is no point in conducting the research. If one of your competitors comes up with a new offering and consumers are clamouring to get it, you certainly don’t need to conduct a research study to see if such a product would survive in the marketplace.

Is Marketing Research Always Correct?

To be sure, marketing research can help companies avoid making mistakes. Take the example of Tim Hortons, a popular coffee chain in Canada, which has been expanding in the United States and internationally. When Tim Hortons first opened drive-thru kiosks in Europe, the service was a flop. Why? Because many cars in Europe don’t have cup holders. Would marketing research have helped? Probably. So would a little bit of market intelligence. It would have been easy for an observer to see that trying to drive a car while holding a cup of hot coffee at the same time is difficult.

That said, we don’t want to leave you with the idea that marketing research is infallible. As we indicated at the beginning of the chapter, the process isn’t foolproof. In fact, marketing research studies have rejected a lot of good ideas. The idea for telephone answering machines was initially rejected following marketing research. So was the hit sitcom Seinfeld, a show that in 2002 TV Guide named the number-one television program of all time. Even the best companies, like Coca-Cola, have made mistakes in marketing research that have led to huge flops. In the next section of this chapter, we’ll discuss the steps related to conducting marketing research. As you will learn, many things can go wrong along the way that can affect the results of research and the conclusions drawn from it.

Key Takeaways

Many marketing problems and opportunities can be solved by gathering information from a company’s daily operations and analyzing it. Market intelligence involves gathering information on a regular, ongoing basis to stay in touch with what’s happening in the marketplace. Marketing research is what a company has to resort to if it can’t answer a question by using market intelligence, internal company data, or analytical software. Marketing research is not infallible, however.

Review and Reflect

- Why do companies gather market intelligence and conduct marketing research?

- What activities are part of market intelligence gathering?

- How do marketing professionals know if they have crossed a line in terms of gathering marketing intelligence?

- How does the time frame for conducting marketing intelligence differ from the time frame in which marketing research data are gathered?

Media Attributions

- Cabela’s © Echo9er is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Zarello, C. (2009, May 5). Hunting for gold in the great outdoors. Retail Information Systems News. Accessed September 13, 2021. ↵

- Zarello, C. (2009, May 5). Hunting for gold in the great outdoors. Retail Information Systems News. Accessed September 13, 2021. ↵

- Gardner, J. (2001, September 24). Competitive intelligence on a shoestring. Inc. Accessed December 14, 2009. ↵

- Miller, L. (2001, August 31). P&G admits to dumpster diving. PRWatch. Accessed December 14, 2009. ↵

- Microsoft suit alleges ex-worker stole trade secrets. (2009, January 30). CNET. Accessed August 1, 2023. ↵

- Anderson, J. (1995, March 25). Bugging Air France first class. Ellensburg Daily News, 3. Accessed December 12, 2009. ↵

software that allows managers who are not computer experts to gather all kinds of different information from a company’s databases

gathering corporate information illegally or unethically