Chapter 3: Consumer Behaviour

3.1 Consumer Decision-Making Process

Learning Objectives

- Understand what the stages of the buying process are and what happens in each stage.

- Distinguish between low-involvement and high-involvement buying decisions.

Stages in the Consumer Decision-Making Process

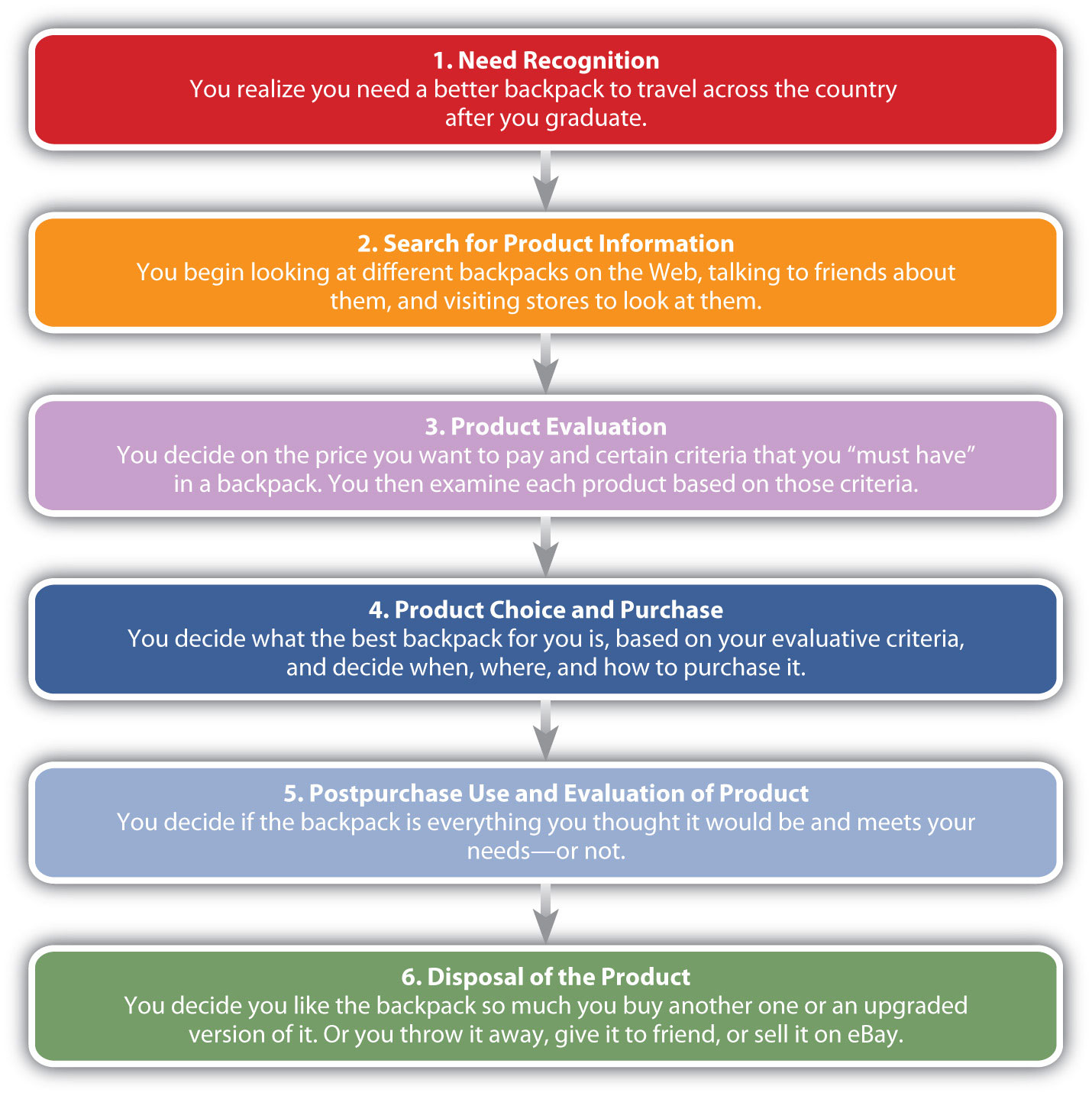

Figure 3.1 outlines the buying stages consumers go through. At any given time, you’re probably in a buying stage for a product or service. You’re thinking about the different types of things you want or need to eventually buy, how you are going to find the best ones at the best price, and where and how you will buy them. Meanwhile, there are other products you have already purchased that you’re evaluating. Some might be better than others. Will you discard them and, if so, how? Then what will you buy? Where does that process start?

Stage 1. Need Recognition

You plan to backpack around the country after you graduate and don’t have a particularly good backpack. You realize that you must get a new backpack. You may also be thinking about the job you’ve accepted after graduation and know that you must get a vehicle to commute. Recognizing a need may involve something as simple as running out of bread or milk or realizing that you must get a new backpack or a car after you graduate. Marketers try to show consumers how their products and services add value and help satisfy needs and wants. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Gatorade, Powerade, and other beverage makers locate their machines in gymnasiums so you see them after a long, tiring workout? Or that you hear a McDonald’s ad on the radio during your morning commute?

Functional vs Psychological Needs

Functional needs refer to the performance of the product or service.

Psychological needs refer to the gratification from the product or service.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

One of the most important humanists, Abraham Maslow (1908–1970), conceptualized personality in terms of a pyramid-shaped hierarchy of motives, also called the Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs will be discussed in further detail in chapter 3.2 “Factors that influence consumers’ buying behaviour”.

Stage 2. Search for (Product) Information

For products such as milk and bread, you may simply recognize the need, go to the store, and buy more. However, if you are purchasing a car for the first time or need a particular type of backpack, you may need to get information on different alternatives. Maybe you have owned several backpacks and know what you like and don’t like about them. Or there might be a particular brand that you’ve purchased in the past that you liked and want to purchase in the future. This considered internal search for information and is a great position for the company that owns the brand to be in—it is something firms strive for. Why? Because it often means you will limit your search and simply buy their brand again.

If what you already know about backpacks doesn’t provide you with enough information, you’ll probably continue to gather information from various sources. People frequently ask friends, family, and neighbours about their experiences with products. Magazines such as Consumer Reports (considered an objective source of information on many consumer products) or Explore might also help you. Similar information sources are available for learning about different makes and models of cars. This is considered external search for information.

Internet shopping sites such as Amazon have become a common source of information about products. Consumer Reports is an example of a non-profit review company. The site offers product ratings, buying tips, and price information. Amazon also offers product reviews written by consumers. People prefer “independent” sources such as this when they are looking for product information. However, they also often consult non-neutral sources of information, such as advertisements, brochures, company websites, and salespeople.

Stage 3. Product Evaluation/Evaluate Alternatives

Obviously, there are hundreds of different backpacks and cars available, and it’s not possible for you to examine all of them. In fact, good salespeople and marketing professionals know that providing you with too many choices can be so overwhelming that you might not buy anything at all. Consequently, you may use heuristics or rules of thumb that provide mental shortcuts in the decision-making process. You may also develop evaluative criteria to help you narrow down your choices. Backpacks or cars that meet your initial criteria before the consideration will determine the set of brands you’ll consider for purchase.

Evaluative criteria are certain characteristics that are important to you such as the price of the backpack, the size, the number of compartments, and the colour. Some of these characteristics are more important than others. For example, the size of the backpack and the price might be more important to you than the colour—unless, say, the colour is hot pink and you hate pink. You must decide what criteria are most important and how well different alternatives meet the criteria.

Companies want to convince you that the evaluative criteria you are considering reflect the strengths of their products. For example, you might not have thought about the weight or durability of the backpack you want to buy. However, a backpack manufacturer such as Osprey might remind you through magazine ads, packaging information, and its website that you should pay attention to these features—features that happen to be key selling points of its backpacks. Automobile manufacturers may have similar models, so don’t be afraid to add criteria to help you evaluate cars in your consideration set.

Consumers don’t have the time or desire to ponder endlessly about every purchase! Fortunately for us, heuristics, also described as shortcuts or mental “rules of thumb”, help us make decisions quickly and painlessly. Heuristics are especially important to draw on when we are faced with choosing among products in a category where we don’t see huge differences or if the outcome isn’t ‘do or die.’

Heuristics are helpful sets of rules that simplify the decision-making process by making it quick and easy for consumers.

Stage 4. Product Choice (Decision) and Purchase

With low-involvement purchases, consumers may go from recognizing a need to purchasing the product. However, for backpacks and cars, you will likely decide which one to purchase after you have evaluated different alternatives. In addition to which backpack or which car, you are probably also making other decisions at this stage, including where and how to purchase the backpack (or car) and on what terms. Maybe the backpack was cheaper at one store than another but the salesperson there was rude. Or maybe you decide to order online because you’re too busy to go to the mall. Other decisions related to the purchase, particularly those related to big-ticket items, are made at this point. For example, if you’re buying a Smart TV, you might look for a store that will offer you a discount or a warranty. Before purchasing an Amazon Prime subscription, you are eligible for a 30-day free trial.

Ritual consumption refers to patterns consumers exhibit that are connected to life events (birthdays, anniversaries) or everyday behaviours (coffee breaks or happy hour).

Stage 5. Post-Purchase Use and Evaluation

At this point in the process, you decide whether the backpack you purchased is everything it was cracked up to be. Hopefully it is, but if it’s not, you’re likely to suffer what’s called post-purchase dissonance or “buyer’s remorse.” Typically, dissonance occurs when a product or service does not meet your expectations. Consumers are more likely to experience dissonance with products that are relatively expensive and purchased infrequently.

You want to feel good about your purchase, but you don’t. You begin to wonder whether you should have waited to get a better price, purchased something else, or gathered more information first. Consumers commonly feel this way, which is a problem for sellers. If you don’t feel good about what you’ve purchased from them, you might return the item and never purchase anything from them again. Or, worse yet, you might tell everyone you know how bad the product was.

Companies do various things to try to prevent buyer’s remorse. For smaller items, they might offer a money-back guarantee or they might encourage their salespeople to tell you what a great purchase you made. How many times have you heard a salesperson say, “That outfit looks so great on you!” For larger items, companies might offer a warranty, along with instruction booklets, and a toll-free troubleshooting line to call or they might have a salesperson call you to see if you need help with a product. Automobile companies may offer loaner cars when you bring your car in for service.

Companies may also try to set expectations in order to satisfy customers. Service companies such as restaurants do this frequently. Think about when the hostess tells you that your table will be ready in 30 minutes. If they seat you in 15 minutes, you are much happier than if they told you that your table would be ready in 15 minutes, but it took 30 minutes to seat you. Similarly, if a store tells you that your pants will be altered in a week and they are ready in three days, you’ll be much more satisfied than if they said your pants would be ready in three days, yet it took a week before they were ready.

Stage 6. Disposal of the Product

There was a time when neither manufacturers nor consumers thought much about how products got disposed of, so long as people bought them. But that’s changed. How products are being disposed of is becoming extremely important to consumers and society in general. Computers and batteries, which leach chemicals into landfills, are a huge problem. Consumers don’t want to degrade the environment if they don’t have to, and companies are becoming more aware of this fact.

Take, for example, Soda Stream, an appliance that makes sparkling water. By using this product, customers don’t have to buy and dispose of plastic bottle after plastic bottle, damaging the environment in the process. Instead of buying new bottles of it all the time, you can make your own carbonated drinks. You have probably noticed that most grocery stores now sell cloth bags consumers can reuse and are charging for paper bags. Ikea, Patagonia and Arc’teryx offer their customers a chance to resell their products back to the company who will in turn sell it on their website.

Other companies are less concerned about conservation than they are about planned obsolescence. Planned obsolescence is a deliberate effort by companies to make their products obsolete, or unusable, after a period of time. The goal is to improve a company’s sales by reducing the amount of time between the repeat purchases consumers make of products. In 2020, Apple was found guilty of deliberately slowing down its older phones so customers would purchase new models.

Products that are disposable are another way in which firms have managed to reduce the amount of time between purchases. Disposable pens are an example. Do you know anyone today that owns a refillable pen? There are many more disposable products today than there were in years past—including everything from bottled water and individually wrapped snacks to single-use eye drops and cell phones. How many disposable masks have you used since the COVID-19 pandemic first started?

Low-involvement and High-involvement Decisions

As you have seen, many factors influence a consumer’s behaviour. Depending on a consumer’s experience and knowledge, some consumers may be able to make quick purchase decisions, while other consumers may need to get information and be more involved in the decision process before making a purchase. The level of involvement reflects how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product and how much information you need to make a decision. The level of involvement in buying decisions may be considered a continuum from decisions that are fairly routine (consumers are not very involved) to decisions that require extensive thought and a high level of involvement. Whether a decision is low, high, or limited, involvement varies by consumer, not by product, though some products such as purchasing a house typically require a high level of involvement for all consumers. Consumers with no experience purchasing a product may have more involvement than someone who is replacing a product. You have probably thought about many products you want or need but never did much more than that. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. When you run out of products such as milk or bread that you buy on a regular basis, you may buy the product as soon as you recognize the need because you do not need to search for information or evaluate alternatives. As Nike would put it, you “just do it.” Low-involvement decisions are, however, typically products that are relatively inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if purchased by mistake.

Consumers often engage in routine response behaviour when they make low-involvement decisions—that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behaviour. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. Similarly, if you run out of Diet Coke at home, you may buy more without any information search. Some low-involvement purchases are made with no planning or previous thought. These buying decisions are called impulse buying. While you’re waiting to check out at the grocery store, perhaps you see a magazine with your favourite celebrity on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. You might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one, or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry or just want them. These are items that are typically low-involvement decisions. Low-involvement decisions aren’t necessarily products purchased on impulse, though they can be.

By contrast, high-involvement decisions carry a higher risk to buyers if they fail, are complex, and/or have high price tags. A car, a house, and an insurance policy are examples. These items are not purchased often but are relevant and important to the buyer. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behaviour when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called “extended problem solving”, where they spend a lot of time comparing different aspects such as the features of the products, prices, and warranties.

High-involvement decisions can cause buyers a great deal of post-purchase dissonance (anxiety) if they are unsure about their purchases or if they have a difficult time deciding between two alternatives. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware that post-purchase dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, they try to offer consumers a lot of information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and how they won’t let the consumer down. Salespeople may be utilized to answer questions and do a lot of customer “hand-holding”.

Limited problem solving falls somewhere between low-involvement (routine) and high-involvement (extended problem solving) decisions. Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a little more information. Assume you need a new backpack for a hiking trip. While you are familiar with backpacks, you know that new features and materials are available since you purchased your last backpack. You’re going to spend some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re travelling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favourite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or, you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way, you shorten or limit your involvement and the decision-making process.

Products, such as chewing gum, which may be low involvement for many consumers often use advertising such as commercials and sales promotions such as coupons to reach many consumers at once. Companies also try to sell products such as gum in as many locations as possible. Many products that are typically high involvement such as automobiles may use more personal selling to answer consumers’ questions. Brand names can also be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low-versus high-involvement decision—say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favourite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behaviour), but you may not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brand or brands. For example, when considering an electric car, some buyers may only consider Tesla. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the manufacturers of products that are typically high-involvement decisions can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

Maybe you already thought of examples from your own decision-making while reading this chapter. Use the exercise below to think through a decision in detail.

Key Takeaways

Consumer behaviour looks at the many reasons why people buy things and later dispose of them. Consumers go through distinct buying phases when they purchase products:

- realizing the need or wanting something,

- searching for information about the item,

- evaluating different alternatives,

- making a decision and purchasing it,

- evaluating the product after the purchase, and

- disposing of the product.

Review and Reflect

- What can marketers do at each stage to influence the customer in their favour?

- What is post-purchase dissonance and what can companies do to reduce it?

- How do low-involvement decisions differ from high-involvement decisions in terms of relevance, price, frequency, and the risks their buyers face? Name some products in each category that you’ve recently purchased.

- What stages do people go through in the buying process for high-involvement decisions? How do the stages vary for low-involvement decisions?

Media Attributions

- Stages of Consumer’s Decision-Making Process © Principles of Marketing is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Osprey Backpack © Melanie Innis is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Recycling Center Pile © jqpubliq is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Disposable Face Mask on street, East Downtown, Vancouver during coronavirus pandemic © GoToVan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a pyramid-shaped hierarchy of motives

certain characteristics that are important to you

when a product or service does not meet expectations of the buyer

a deliberate effort by companies to make their products obsolete, or unusable, after a period of time