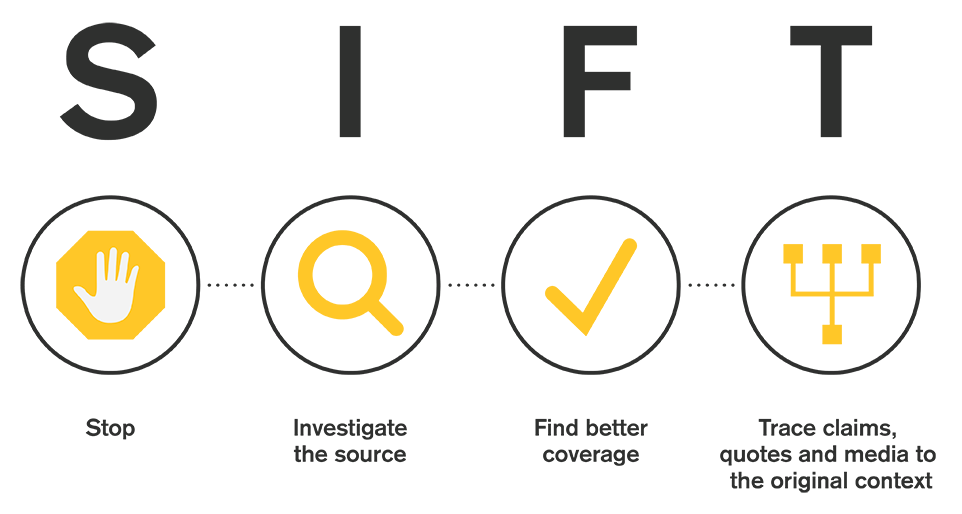

30 Beyond Checklists: The SIFT Method

So far we’ve looked at ways to evaluate sources of information according to some fairly simple criteria. Now it’s time to dig a little deeper and learn to ask questions about a source that can help you quickly decide whether to trust it or move on to find something better.

What follows is an adaptation of the SIFT (The Four Moves) method, a strategy for making a quick assessment as to whether or not a source of information is reliable and worthy of your attention. This method was developed to teach college students a shorter version of what experienced fact-checkers regularly do when confronted with news sources that are unfamiliar.

Move #1: STOP

The first thing to do when looking at a source of information is to STOP. Take a brief pause and ask yourself what you already know about the author, publication or website. Are they familiar to you? Do you already know them to be a reliable source?

ACTIVITY: Do you know these sites?

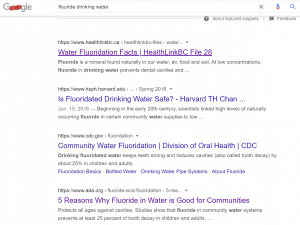

You are researching the topic of whether municipalities should add fluoride to public drinking water. The screenshot below shows a snip of some of the top results for this search. Most of the sites, or at least their domains, should be easily recognizable: Harvard School of Public Health (.edu) and the Centres for Disease Control (.gov).

Even if you do not recognize HealthLinkBC, a simple click on the link [link opens in a new tab], would indicate that it is part of the BC Ministry of Health (.gov.bc.ca).

(Click on the image to enlarge it. Use your browser’s back button to return to this page.)

If you are confident that your sources are known to be reliable, you don’t need to go any further. But if you are not familiar with an author or site, consider using the next 3 moves.

Move #2: INVESTIGATE THE SOURCE

Exploring the source means finding out whatever you can about its author, publisher, sponsoring organizations and partners and so on, before you spend too much time reading it. Knowing the context of a source will help you to be aware of any potential biases, hidden agendas or purposes, and even misinformation.

A key part of this move is to use something that digital literacy experts call “lateral reading“. Making a habit of reading through various external sources about your source will help you assess its credibility and appropriateness for your research. This involves getting off the page, opening up a new tab (or three!) and investigating the source itself. In their initial stages of information gathering, fact-checkers frequently use this strategy, investing some time in reading about the site up front, before turning their attention to the content.

ACTIVITY: What can you determine about this site?

The previous search on fluoride and public drinking water also led to this result, a story on the website Natural News. (Link opens in a new tab. Keep it open to answer some questions about the site.)

Never heard of Natural News? Now is the time to investigate this source!

Open a new tab or window and do a quick Google search for the website or the owner’s name. (You can find his name on the About page of the website.) Scan the first few results. How is the website or its owner regarded by other sources, namely the mainstream press and Wikipedia?

Open another tab and do a quick search for the topic fluoride and drinking water. Notice that the Water Fluoridation page on Wikipedia includes a link to controversy surrounding this topic. Go one step further and open the Talk page for this article. What do the comments from Wikipedia editors indicate?

Head back to the Natural News story. What might the heavy presence of advertisements for various alternative and natural health products suggest about the purpose of this site?

Move #3 FIND BETTER COVERAGE

Investing a bit of time up front in order to determine the quality of a site will pay off. Look around for better coverage of your topic, whether this means re-wording your initial search or following the references of other sites. What you are aiming for is an understanding of the context of a topic and who the credible authors and organizations are that can provide consensus and agreement.

Remember, you are not obligated to stay with any specific source. Keep looking, and you will find something better.

ACTIVITY: Can you find a better source?

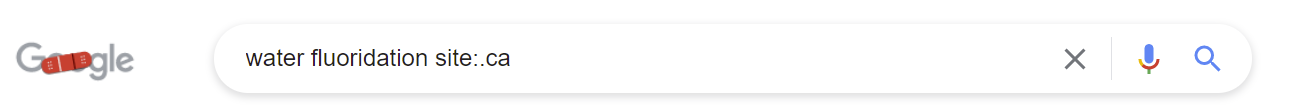

It is beyond the scope of this section to provide all the tips for better searching in Google, but there is one strategy you might consider using for our water fluoridation topic: the site or domain limit in Advanced Google search. For this subject, it might be appropriate to consider searching educational sites or perhaps Canadian governmental sites, which would include information from scientists and public health professionals.

Going back to Google and trying a new search for water fluoridation, see what happens when you limit the search to the domain .edu or .ca.

Click the images below to see the results list. Where are the majority of sites coming from?

Move #4 TRACE CLAIMS QUOTES AND MEDIA TO THE ORIGINAL CONTEXT

Much of what we find online comes to us out of context and sometimes could be a misrepresentation of original stories, reports or findings, either intentional or by mistake. If the source you are considering claims justification through citing research or referring to an earlier source, go one step further and trace back to the original. Did the source get it right? Have they distorted findings or only partially considered what was reported?

ACTIVITY: Find the original source

Our earlier Natural News story included a reference to an article published in the journal Environmental Health. However, rather than linking out to the scientific article, the author of the story instead points to other Natural News pieces on the topic, making it difficult for the reader to assess the accuracy of the claim and ultimately casting doubt about the trustworthiness of this site.

Checking for the original article using the library’s Summon search, you can see for yourself that the authors conclude that any association between levels of fluoridation and ADHD warrants further study. A Google search of the article shows several leading scientific journals point out methodological flaws of the study and caution against making causal connections.

Making use of one or more of these strategies will ultimately lead you to better information.

Sources

Text and graphic adapted from SIFT (The Four Moves) by Mike Caulfield is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Text adapted from Teaching Lateral Reading by Stanford History Education Group is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

“Water Fluoridation Found to Increase Hypthyroidism Risk by 30%” (2018) from Natural News.

“Water Fluoridation” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 4.1 The <a href=”https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/”>SIFT Method</a> of online source evaluation.

Article: Malin, A. J., & Till, C. (2015). Exposure to fluoridated water and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States: an ecological association. Environmental Health : A Global Access Science Source, 14, 17 https://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12940-015-0003-1.