Introduction

Gregory Millard

Fascism is an unusual ideology. First, its name has become a universal term of abuse. Hardly anyone self-defines as fascist anymore, and certainly no one aspiring to political power does so; to be called a “fascist” is to be denounced, as the existence of movements such as Antifa illustrates. Second, it was remarkably short-lived as a mainstream force. Fascism exerted impressive political influence for only a single generation, blossoming dramatically in the 1920s and 1930s and then immolating in a catastrophe substantially of fascists’ own making: the Second World War.

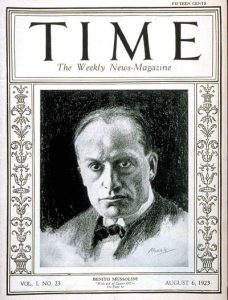

Benito Mussolini’s invention of the word “fascism” (fascismo) is derived from fascio, the Italian word for bundle or sheaf, which had long been used to convey militant solidarity (Paxton, 2005, p. 4). Having ascended to power in Italy in 1922, Mussolini led a fascist dictatorship that helped inspire Adolf Hitler, whose Nazi Party took office in Germany in 1933. Over the 1930s, fascism enjoyed considerable electoral success in Hungary and Romania while also emerging as a relevant force in Spain, Belgium, and (arguably) France and Britain (Paxton, 2005, pp. 68-75). Japan in the same era is often described as fascist (Paxton, 2005, p. 198). North America was not immune; far-right politics and an outright fascist party coalesced in Canada, centred in Québec, during the same period. A fascist rally in New York’s Madison Square Garden attracted 20,000 Swastika-waving attendees in 1939.

Yet within six years of that event, fascism collapsed. The total defeat of the fascist-aligned Axis powers in World War Two brought the spread of fascism to a sudden halt and wiped out the political and symbolic structures it had created. The fascist powers’ causal role in this apocalyptic global war and the genocidal horrors of the Holocaust – cataclysms that killed somewhere between 35 and 60 million people – made explicit fascist politics taboo thereafter (Paxton, 2005, p. 174).

In historical terms, then, fascism was born, rapidly went nova, and suddenly blinked out. By contrast, while the influence of ideologies such as liberalism, socialism, and feminism has waxed and waned in particular periods, their appeal has been much more consistently enduring across generations.

As is true of some other categories explored in this text, such as conservatism and populism, not everyone accepts that fascism is an ideology proper. The fascist is always more concerned with one specific community, valorizing it over others, than the more universal outlook typical of most ideologies. Furthermore, some scholars point out that classical fascist parties and leaders adopted fluid platforms that they did not take especially seriously (e.g., Paxton, 2005, pp. 15-18).

The fascist [wanted] to bring his people into a higher realm of politics that they would experience sensually: the warmth of belonging to a race now fully aware of its identity, historic destiny, and power; the excitement of participating in a vast collective enterprise; the gratification of submerging oneself in a wave of shared feelings, and of sacrificing one’s petty concerns for the group’s good; and the thrill of domination (Paxton, 2005, p. 17).

While fascist politicians were neither the first nor the last to take a casual attitude to programs and position statements, the view that fascism is essentially irrational – not about ideas but rather about feelings, will, and action for action’s sake – is sometimes used to deny that fascism is a political ideology proper. Certainly, fascism boasts no iconic thinkers of world-historical significance as do rival configurations such as liberalism (Mill, Locke) or socialism (Marx, Engels). The closest fascism comes to a classic text is The Doctrine of Fascism(pdf) by Mussolini and Giovanni Gentile.

Other analysts, bewildered by the diversity of phenomena that have been labeled “fascist” over the years, even doubt whether the term is useful (see: Griffin, 2018, p. 32). This is probably going too far. All social phenomena are complex and diverse, but this does not necessarily mean we should abandon generalizations about them.

Media Attributions

- Benito Mussolini Time cover 1923 © Time Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license