Introduction

Serbulent Turan

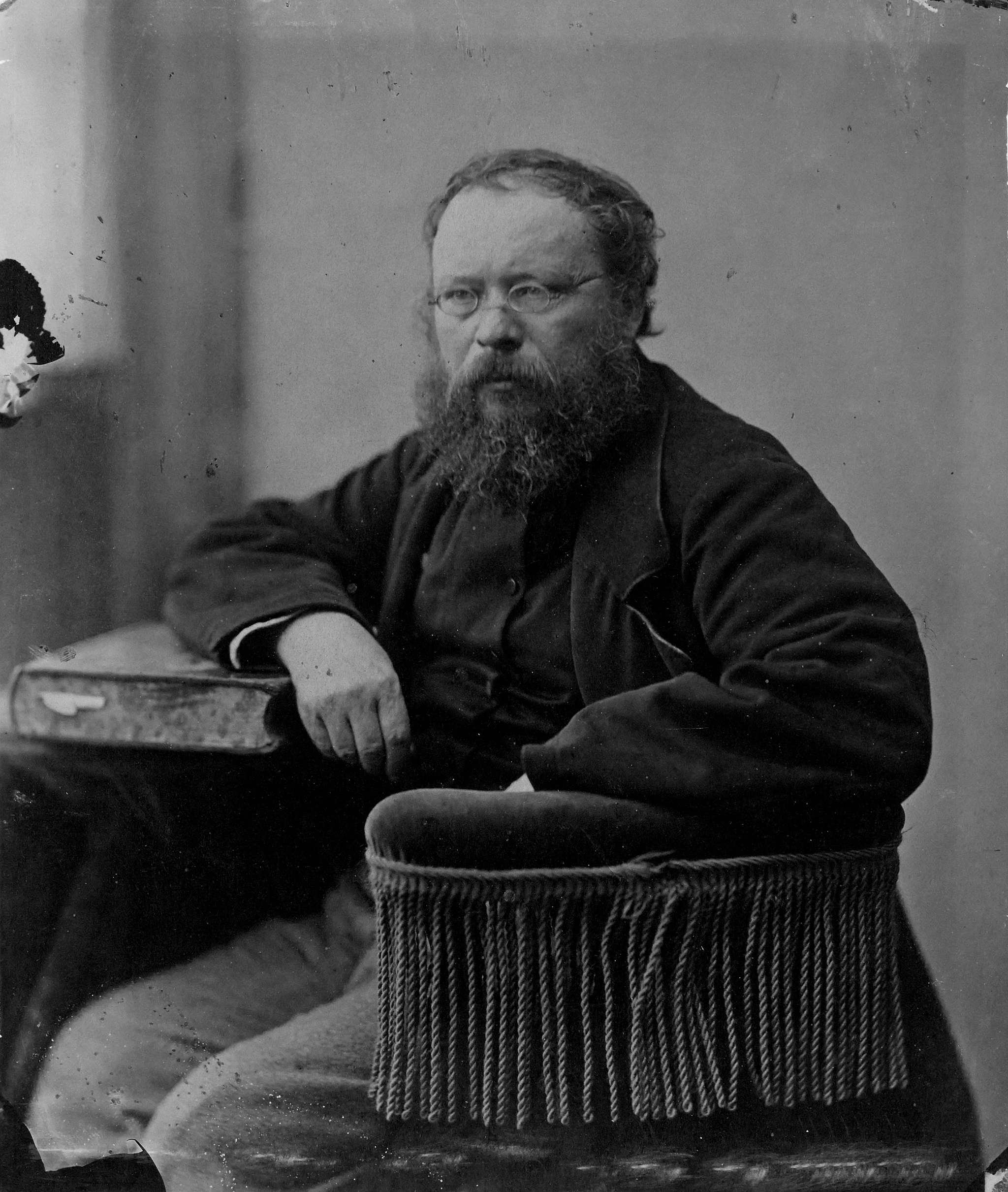

“Whosoever lays a hand on me in order to govern me is a usurper and a tyrant; I declare him my enemy” wrote the 19th-century philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1849). His statement captures the core of what is one of the oldest and most diverse political philosophies of the human experience: the rejection of institutionalized, permanent leadership and coercive government in order to preserve individual and societal freedoms. Indeed, the etymological origins of the word “anarchy” come from the Greek anarkhia, meaning without (an-) ruler (arkhos). Beyond a definite consensus on the rejection of permanent political authority, however, it is not easy to define anarchism. Partly due to its long history and partly because of the immense complexity of the political structures anarchists seek to abolish and replace, there is a wide variety of interpretations of anarchist thought, some of which can be at odds with each other. Accordingly, anarchism is best understood as a collection of practices and philosophical traditions that seek to dissolve hierarchical political power into horizontal, egalitarian organizations of willing individuals and groups. That being acknowledged, most anarchists see themselves as on the far left of the political spectrum and identify as anti-capitalists and anti-fascists. Historically, anarchism has been associated with socialism, with which it shares a number of assumptions and aims, diverging most notably on the abolishment of the state and its institutions. In fact, socialist thought owes some of its formative concepts to William Godwin, the first modern anarchist, whose theories on men’s inherent equality and the illegitimacy of political institutions profoundly influenced European revolutionary thought during and after the French Revolution. Much like socialists, anarchists aim to end the exploitation of labor and establish genuine equality in society. But whereas socialists seek to capture the state power needed to carry out the political revolution, anarchists seek to create popular grassroots organizations to carry out a social revolution and abolish the state and its institutions.

Societies without permanent political structures are as old as humanity, dating back to before the establishment of the first cities, realms, and empires. They exist today throughout the globe, in particular in indigenous and semi-nomadic populations where leadership is often task-based and temporary. The formal codification and definition of anarchism and its main principles, however, date back to the revolutions in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries (see Proudhon on To Be Governed). Anarchist groups and thinkers have been involved in rebellions and revolutions since, most notably the Springtime of Peoples in the 19th century and the Russian and Spanish civil wars in the 20th century. Following a period of relative quiet during the Cold War, anarchist political movements are on the rise once more, focusing on grassroots methods to create and support workers’ movements and joining anti-capitalist and climate justice struggles. While anarchists argue that only a true transformation of society can bring about a real political revolution, anarchism’s critics describe it as utopian, unrealistic, and often dangerous.

Proudhon on To Be Governed

“To be GOVERNED is to be kept in sight, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, estimated, valued, censured, commanded, by creatures who have neither the right, nor the wisdom, nor the virtue to do so… To be GOVERNED is to be at every operation, at every transaction, noted, registered, enrolled, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished. It is, under pretext of public utility, and in the name of the general interest, to be placed under contribution, trained, ransomed, exploited, monopolized, extorted, squeezed, mystified, robbed; then at the slightest resistance, the first word of complaint, to be repressed, fined, despised, harassed, tracked, abused, clubbed, disarmed, choked, imprisoned, judged, condemned, shot, deported, sacrificed, sold, betrayed; and, to crown all, mocked, ridiculed, outraged, dishonoured. That is government; that is its justice; that is its morality” (Proudhon, 1851).

Media Attributions

- Portrait Pierre-Joseph Proudhon © Nadar is licensed under a Public Domain license