7.2.3 Types of Nationalism: the Case of Québec

Frédérick Guillaume Dufour and Dave Poitras

During the second half of the 20th century, Canadian politics was punctuated by important rounds of constitutional debate regarding the status of Québec in the Canadian federation (Gagnon, 2004). In fact, the history of Québec has been shaped by multiple episodes of political contention, several of which have implied republican or nationalist claims. In 1837, a political movement, Les patriotes, inspired in large part by the political institutions of the young United States of America, took arms in order to fight British troops in Lower Canada and demanded representative political institutions and an elected representative body. It was forcefully suppressed by British military forces. For most of the following century, the Catholic Church, the French-language, and le code civil remained at the core of French-Canadian identity. It was during the middle of the twentieth century that new political forces in Québec merged into a state-seeking nationalism. They opposed what they perceived as linguistic and economic oppression caused by an Anglo-dominated Canada bestriding the political institutions of the Dominion.

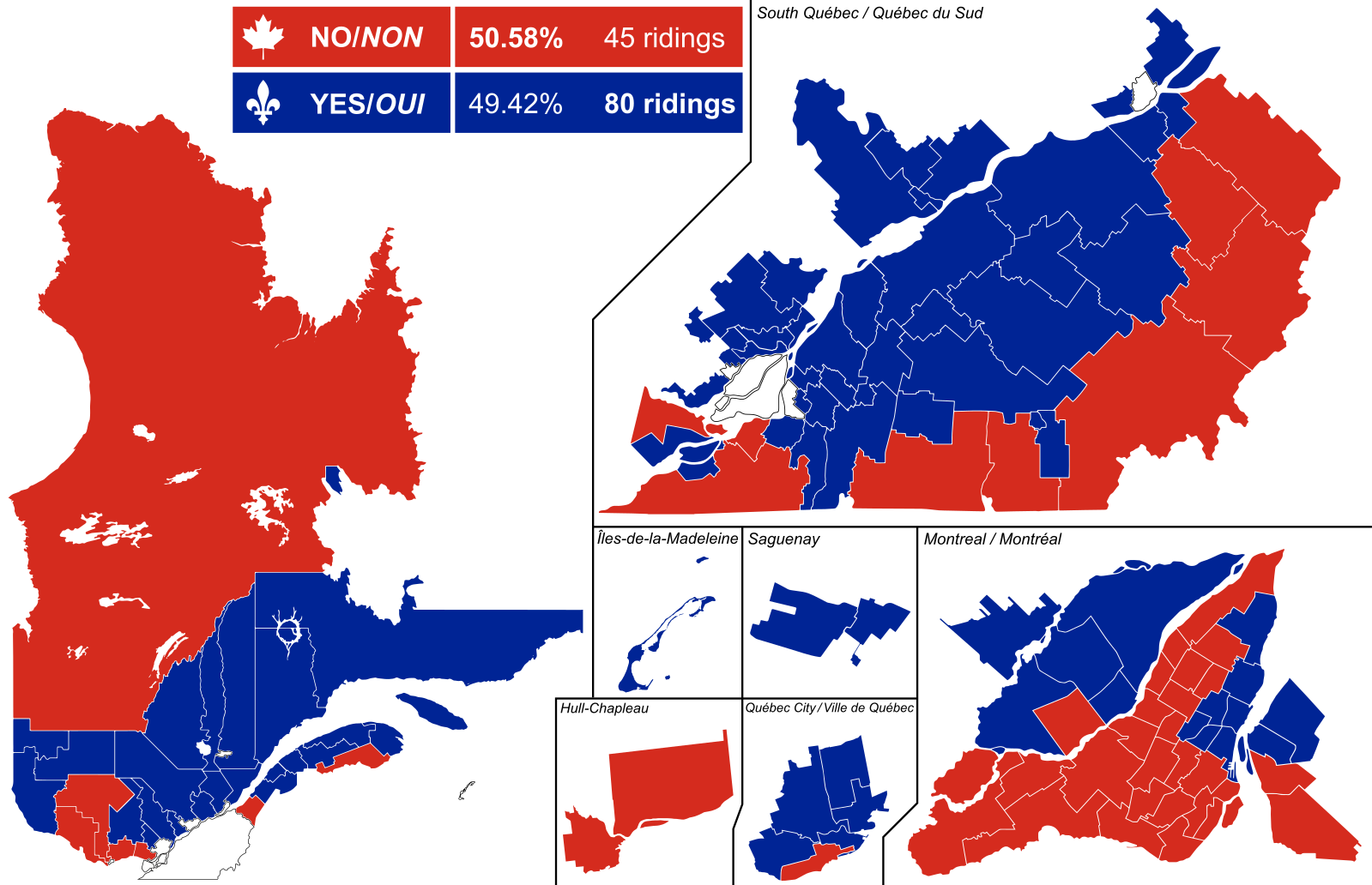

During the nineteen sixties, the Révolution Tranquille swiftly transformed the relationship between the province and the Catholic religion and its clergy, leaving the door wide open for outside influences and Québécois eager for novelty. Alongside this, an important national-liberation movement took root. The once-disparate movement promptly consolidated into an influential political formation during the nineteen seventies, le Parti Québécois. Since then, important constitutional litigations (such as the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Accord) as well as two referendums have been held in Quebec on the status of the province in Canada. At the core of the referendums was the idea that Québec should become a sovereign country from Canada. The second referendum in 1995 came very close to a victory of the camp in favour of Québec’s sovereignty. It won 49.5% of the vote, while the camp in favour of remaining in the federation won 50.5%. Since the beginning of the year 2000, the sovereignist option in Québec has held an approval rating slightly below 40%. Although the sovereigntist movement seems to be in decline, claims-making in favour of more autonomy for Québec, a more decentralized federation, and an asymmetric conception of the federation remain popular.

While the sovereignist movement has not succeeded in transforming the province of Québec into an independent state, it may be argued that this movement nevertheless made it a nation. Before the sixties, citizens of the province would mostly refer to themselves as French Canadians, whereas today they mainly consider themselves as Québécois, with French Canadians being the French-speaking Canadians living in the other provinces of Canada.

Media Attributions

- Monument Patriotes Pied-du-Courant © Jean Gagnon is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Quebec referendum,1995 – Results By Riding (Simple Map) © Dr. Random Factor is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license