6.2 Anarchy in the 20th Century and Today

Serbulent Turan

Anarchism in the 20th century was marked by a strong paradox: The first half of the century saw the golden age of anarchist thought and action, with anarchists playing important roles and making substantial political gains from Asia to Europe to North America. The second half of the century, on the other hand, saw the retreat of anarchist thought into the margins of political struggles, with “anarchism” in the public eye largely becoming a synonym for a complete lack of order and aimless chaos and violence. Much of this latter development can be explained by the bipolar world of the Cold War era and the stark division of the global political order between capitalist democracies and state-socialisms, both of which saw anarchism as a threat to their institutionalized order.

Watch this short video to learn more about the Cold War:

Video 6.1. The Cold War by Geo History.

At the turn of the century, anarchist movements across the globe inherited a strong heritage of political action. Anarchists were present across the political spectrum, from violent political action to philosophy and literature. While anarchist labor organizations were notable parts of the global struggles for the five-day workweek and eight-hour workday (from the previous seven days of 12 to 14 hours of work), other anarchists took to violence, and yet others published and agitated. Anarchists killed kings, nobles, presidents and parliamentarians (for instance, the Italian anarchist Gaetano Bresci shot and killed King Umberto of Italy in 1900; in 1901, the American anarchist Leon Czolgosz shot and killed US President William McKinley). In the philosophical realm, anarchism was making splashes as well: one of the most influential anarchists of the time, Peter Kropotkin, who was once a Russian Prince and aid to the Tzar before stepping down for his ideals, published his Mutual Aid in 1902. Anarchist communes and groups played major roles in numerous uprisings in Europe and beyond. Following the First World War in particular, widespread disillusionment with the economic and political systems further fueled anarchist movements and even gave rise to the world’s first anarchist territory in Ukraine (see Ukrainian Free Territory). Anarchists also had a major presence in the Spanish Civil War and resisted the fascist takeover alongside communist forces. As could be expected, anarchists were present in all resistance movements fighting the Nazi occupation, and they even formed loosely organized guerilla forces throughout Europe.

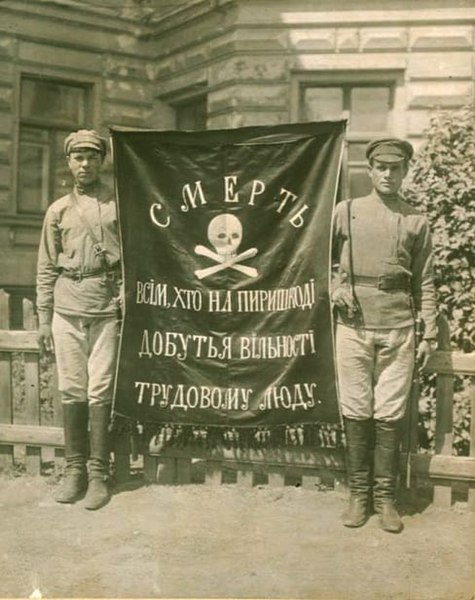

Ukrainian Free Territory (1918 to 1921)

The Free Territory was a large swath of Ukraine managed by free Soviets (workers’ associations) and communes that federated closely to form the world’s first Stateless-Libertarian territory. It was protected in its operation by the ‘Revolutionary Insurrectionary Anarchist Army,’ a large collection of anarchist guerilla bands that fought in the Russian Civil War. The Insurrectionary Anarchist army was widely known as the Black Army, named so in rivalry to the communists’ Red Army and monarchists’ White Army.

Numbering between 20,000 and 100,000 troops with its irregular members, the Black Army marched under the anarchist slogan “Land to the peasants, factories to the workers.” The Black Army led an uneasy alliance with the Red Army against the monarchist forces in the Civil War, and the combined anarchist-communist forces defeated the Tzarist armies. However, as soon as victory was on the horizon, the communist forces turned on the anarchists, and through a series of scorched earth tactics (burning the land, killing all inhabitants) they managed to isolate the Black Army, finally annihilating its regular forces after sending over 300,000 troops against it. The remaining forces of the anarchists dispersed into the rest of Ukraine and continued to wage guerilla operations until well into the 1940s (Eikhenbaum, 1974).

The relatively stable bipolar world order following the Second World War left little room for anarchism as both poles – authoritarian communism and liberal capitalism – fought to silence alternative ideologies. Despite a concerted effort from the world’s superpowers, however, anarchist communes blossomed wherever they could find room, from the freed territories in Denmark, to Kibbutzim in Israel, to communes in San Francisco. Anarchism, however, ceased to be perceived as a major world ideology, and was demoted in the public eye to disorganized chaos and meaningless violence. In the absence of diminished militantism and direct political action, literary anarchism became the main stream of anarchist presence, continuing a strong tradition of anarchistic education theory (like the Ferrer and Moderna schools). Thinkers and writers such as Robert Paul Wolff, John Simmons, and James C. Scott have been prolific in arguing the case of anarchy in history, philosophy, and political science.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it seemed, momentarily, that capitalist liberal democracies had won the day. Disillusionment soon followed, however, and faced with tremendous economic inequality and collapsing ecological systems, anarchistic communes and movements are resurfacing throughout the globe. Workers’ collectives, associations, syndicates, anti-fascist organizations, climate justice movements, feminist and LGBTQI+ movements, and even local electoral politics have become fertile grounds for social anarchists seeking to engage in direct political action. Indeed, compared to a few decades ago, it is safe to say that anarchists and anarchism are making a strong and visible comeback.

Watch this short video summarizing the history of anarchism:

Video 6.2. Introduction to the History of Anarchism by Then & Now.

Discussion Questions

As a political theory, anarchy remains a controversial proposal.

- Do you believe society can function without a state? What would that look like?

- Anarchists believe that men are rational and ultimately capable of governing themselves and that coercive governments that use force are more of a threat than a help. Would you agree?

- Anarchists argue that most humans are inherently good natured and, if left alone, would often form supportive groups based on equality and collaboration. In other words, cooperation, and not conflict, is the basic rule of humanity. Do you agree?

- Anarchists, in particular in the past, always had a strong preference for direct militant political action often amounting to bombings and assassinations. Anarchists justified these methods as ‘self-defense’ in the face of despots that forcibly imposed their rule on an unwilling population. Are these methods justifiable in our time?

Media Attributions

- Один из лозунгов махновцев © unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license