6.1.1 Social Anarchism

Serbulent Turan

Social anarchism is a category that comprises the collectivist or socialist wing of anarchist thought. Social anarchism has been and remains the dominant form of anarchist thought, so much so, in fact, that the most common usage of the term ‘anarchism’ refers to social anarchism. Indeed, social anarchism has historically always been more engaged with political struggles and conflicts. It prioritizes community, cooperation, and social freedoms, seeing them as necessary for and complimentary to individual freedoms.

To social anarchists, the state is an undeniably oppressive institution that inhibits freedoms and forcibly prevents or destroys collectivist organizations: What the state cannot control, it seeks to destroy. Different forms of social anarchism such as anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, social-libertarianism, and collectivism have played major roles in numerous revolutions. As a political project, social anarchists seek to replace the state with smaller-scale, naturally democratic collectives that organically emerge from life: workers’ cooperatives that allow workers to collectively own and manage factories, citizens’ assemblies that allow direct democratic participation in decision making in communities and cities, and horizontally connected citizens’ confederations that will eventually replace the state through bottom-up organization. Thus, anarchists from this school of thought are involved in struggles on both smaller and larger scales, from establishing and defending workers’ cooperatives, associations, and trade unions, to armed uprisings and assassinations. Other politically engaged groups like anarcho-feminists (see Emma Goldman) and green-anarchists prioritize forming grassroots organic groupings and establishing horizontal alliances.

To Go Further: Various Forms of Social Anarchism Briefly Explained

- anarcho-communism aims to establish geographical communities collectively owning the land and ruled in every way through direct-democracy;

- anarcho-syndicalism focuses on worker’s cooperatives, trade unions, and horizontal alliances between those;

- social-libertarianism largely aims to shake off all authority and create individualistic communes each with their own rules;

- collectivism is aiming for similar communities but giving priority to the group over the individual;

- anarcho-feminism is focusing largely on gender inequalities and aiming to dismantles structures of patriarchy;

- green-anarchists prioritize human to non-human interactions, seeking to dismantle men’s domination of the environment.

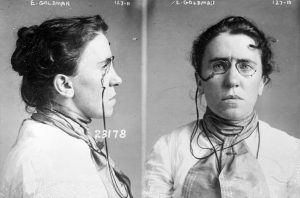

Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution”

Emma Goldman is one of the most famous anarchists of the 20th century. A theorist, agitator, prisoner, and would-be assassin, Goldman played an immense role in developing and popularizing anarchism in North America. She was present and fought in several of the major events of 20th century, including the Russian October Revolution and the Spanish Civil War. Today, she is best known for her tireless feminist work. One of the most famous quotes attributed to her – ‘If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution’ – is derived from her own memoires. She writes:

At the dances I was one of the most untiring and gayest. One evening a cousin of Sasha [Alexander Berkman], a young boy, took me aside. With a grave face, as if he were about to announce the death of a dear comrade, he whispered to me that it did not behoove an agitator to dance. Certainly not with such reckless abandon, anyway. It was undignified for one who was on the way to become a force in the anarchist movement. My frivolity would only hurt the Cause. I grew furious at the impudent interference of the boy. I told him to mind his own business, I was tired of having the Cause constantly thrown into my face. I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from conventions and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy. I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to become a nun and that the movement should not be turned into a cloister. If it meant that, I did not want it. ‘I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.’ Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world–prisons, persecution, everything. Yes, even in spite of the condemnation of my own comrades I would live my beautiful ideal. (1934, p. 56)

Media Attributions

- Anarchist flag © Trevor Dykstra is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Emma Goldman 1901 mugshot © Bain News Service is licensed under a Public Domain license