11.2.1 The Christian Right as Religious Fundamentalism

Gregory Millard

As with all fundamentalisms, the Christian right is in revolt against what it perceives as a sustained and ongoing assault against its religious identity. During the last three decades of the 20th century, the Christian right often used the term ‘secular humanism’ to describe the many-headed Hydra that its members believe is ‘waging a culture war on religious conservatives, undermining traditional values and religious practice’ (Wilcox, 2011:27).

Their proofs of this are many:

- The abandonment of prayer in public schools;

- The teaching of evolution without giving equal time to Biblical ‘creationism’ or ‘intelligent design’;

- The 1960s counter-culture that challenged censorious attitudes toward sex, drugs, and self-expression and took a critical view of established authority, including the military and police;

- New waves of feminism, along with rising challenges to patriarchal gender roles, heteronormativity, and even to gender itself, as with demands for trans rights and legal recognition of same-sex marriage;

- Increased legal access to abortion;

- Changing attitudes, technologies, and practices around both birth and death, e.g., stem-cell research using human embryos and the rise of medically assisted dying;

- Declining marriage rates, rising divorce rates, and an increase in non-traditional family arrangements in many societies over the past half-century;

- Permissive attitudes to sex and pornography, and a perceived increase in lewdness and violence in entertainment of all sorts, from movies to music to video games.

The Christian right deplores such phenomena. It sees them as flowing from a moral corruption that spreads like a malignancy once a society abandons God. Moreover, through the expansion of social programs and the welfare state (and, in America, forced racial desegregation) the government has extended its power into areas of life best left to individual conscience, churches, and private charities (Bowman, 2018: 201-213).

Indeed, for many fundamentalists, when a society abandons God, it invites divine retribution. According to biblical texts, God rewarded his chosen people, Israel, with prosperity and power when they were faithful to him and punished them with humiliation and conquest when they strayed. The thought is that He will do the same to nations today. Social, political, and economic disfunction can thus be explained as signs or symptoms of God’s displeasure (Wilcox, 2011: 224).

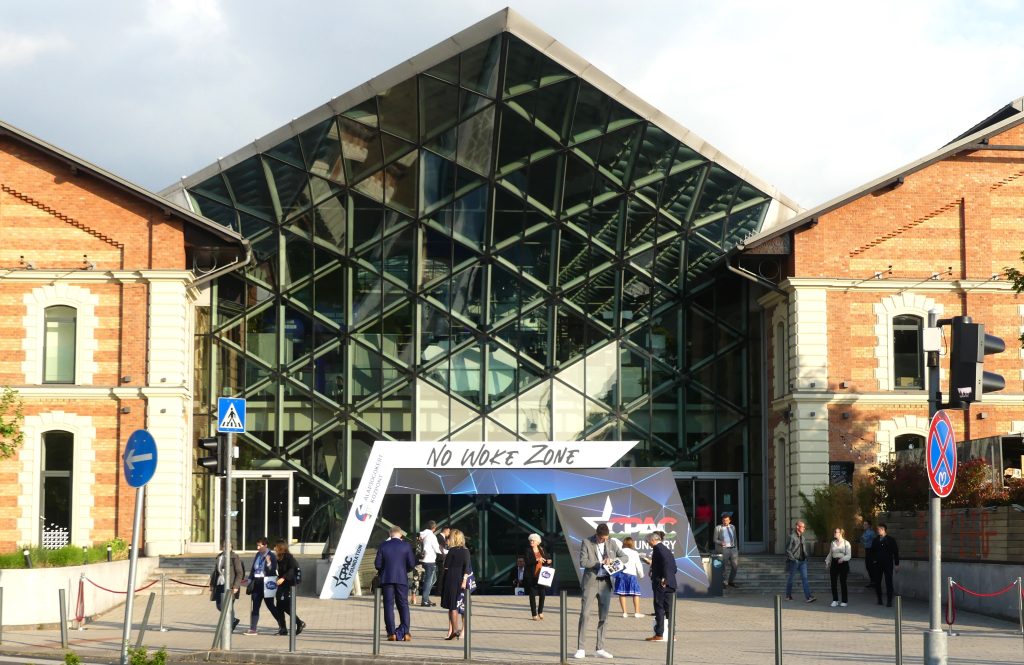

In the 21st century, the Christian right’s terms of engagement shifted somewhat. After 9/11, ‘radical Islam’ – seldom clearly distinguished from Islam as such – tended to supplant ‘secular humanism’ as the named target (FitzGerald, 2017: 475; Boerl and Donvaband, 2015: 80-84). By the late 2010s, the focus of fundamentalist ire shifted yet again, toward what some might call the ‘woke left:’ a loose configuration associated with ‘Critical Race Theory,’ critical gender ideology, anti-capitalism, and other challenges to traditional identity and power hierarchies. Each of these moving targets represent more or less the same thing in Christian fundamentalist thought: an assault on the moral foundations of society. This assault has to be resisted in the name of traditional morality and absolute truth.

The answer, then, is to transform society. The nation needs to become a Christian nation. Its governments, its judges, its schools, its elites and a critical mass of its citizens all need to embrace (or ‘return to’) explicitly Christian values. At the very least, Christian fundamentalists need to ally with religious Jews and Roman Catholics to ensure that the nation affirms the supremacy of the Judeo-Christian God and His principles. In terms of policy, this means rolling back the list of perceived evils catalogued four paragraphs ago. It also means a robust ‘law and order’ agenda (including increased spending on military and police to push back against the chaos unleashed by moral corruption), lower taxes, and a constrained welfare state. In a nutshell, the Christian right links a loose economic libertarianism – low taxes and low regulation with an emphasis on either individual self-reliance or reliance on family, churches, and voluntary charity as support systems – with an unyielding social conservatism that upholds traditional familial, gender, religious, and even economic hierarchies (Himmelstein, 2007).

Media Attributions

- Donald Trump Speech Awake Not Woke © Vox España is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- No Woke Zone © Elekes Andor is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license