1.3.3 Left and Right on the Ground: Local Ideological Spectrums

Gregory Millard

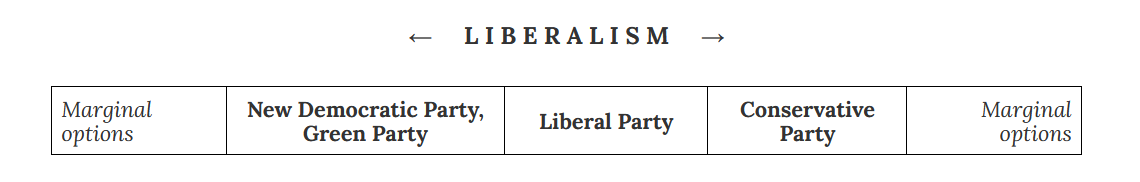

The preceding has explored what we might call an absolute ideological spectrum. It encompasses all the major ideological options of modern politics. However, since the Second World War, the day-to-day politics of most liberal democracies has tended to work within a much narrower band of possibilities. For example, communism and fascism exist only at the very fringes of Canadian political life. Canada’s Marxist-Leninist Party received a paltry 4,124 votes out of 18,350,359 votes cast in the 2019 federal election (Elections Canada, 2019). This is fewer than half the votes received by the satirical Rhinoceros Party, and only a fraction of the total number of spoiled ballots! Meanwhile, there is no self-defined fascist party in Canada at all. Instead, political debate in Canada clusters very heavily around the centre of the absolute ideological continuum. Liberal ideology is thus at the core of Canadian politics, with support shading off toward the left in the form of very moderate social-democratic beliefs on the one hand and a largely moderate conservatism on the right. Indeed, seen from the perspective of the absolute ideological continuum, most of the heated debates within Canadian life – e.g., should Canada adopt a national Pharmacare program? A carbon tax? A pipeline? A higher or lower level of government deficit? – concern minor policy disagreements within a broadly shared allegiance to liberal-democratic capitalism and a global order defined by sovereign states or nations. So when we talk about left and right in Canadian politics, we refer to something much more confined than the absolute ideological spectrum. And something similar holds for politics in most contemporary liberal democracies, most of the time.

At this local level, the political centre – meaning the median point between the most relevant political polarizations within a particular society – does tend to shift leftwards or rightwards as time passes. The political mainstream in Canada in the 1990s hewed further to the right in its commitment to balanced budgets and high tolerance for material inequalities than did the political mainstream of the 1960s, or, arguably, that of the 2020s. And Canada is usually thought to lean further left, on the whole, than the United States; yet many European countries, especially the Scandinavian ones, show much stronger commitments to the redistribution of wealth and material equality than Canada. What exactly counts as the “centre” of mainstream politics, then, varies from society to society, even as each of those societies leans further left or right, and back again, as it moves through time.