1.1 Ideology as a Justification for Error and Oppression

Dr. Gregory Millard

The origin of the term “ideology” is often traced back to Antoine Destutt De Tracy (1754–1836). De Tracy used it to denote a “science of ideas” that, he thought, would help us understand why people believe what they believe. He hoped this science could then be used to root out error and superstition – wrong beliefs, in other words. If we can figure out the causes of such errors, we might be able to eliminate those causes and build a more rational society.

Living as we do in a time of accusations of “fake news” and bizarre conspiracy theories like QAnon, De Tracy’s project might seem tempting. His use of the term “ideology” is not, however, what we typically mean by the word. The project has another problem – that of knowing what is “correct” versus a false belief. De Tracy seems to have thought this was evident, but most philosophers will tell you that it can be a challenging matter.

Instead of embracing De Tracy’s definition, many after him have focused on the “false belief” element and defined ideology as a particular category of false belief. In its more sophisticated forms, this approach sees ideology as the belief system that conditions us to accept and support a specific way of organizing society, even though it may not be in our own best interest.

Ideology, from this perspective, is what justifies the economic, political, and social order we live in. If that order is corrupt, then ideology is a key part of the rip-off – a way of deluding exploited people into thinking their exploitation is necessary, normal, or maybe even fair and reasonable. This view of ideology is most closely associated with Karl Marx (1813–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), the founders of what we now call (ironically, perhaps!) the ideology of Marxism (see chapter V in this textbook). They analyzed and critiqued the capitalist economic system that was enveloping Europe in the 19th century and, in some form, continues to dominate the globe today. For Marx and Engels, the capitalist economy is fundamentally exploitative: it privileges one class, namely those who own capital and businesses (i.e., the capitalist class, also called the bourgeoisie), and subordinates everyone else – particularly the workers, or proletariat, who have no choice but to sell their labour to the owners of the businesses. But why would anyone other than capitalists support such a system? Why would you, as an exploited worker, believe this system is acceptable, even necessary?

The answer, Marx and Engels suggest, is that you have been deluded by ideology. “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas,” they write (Marx and Engels, 1932). We have been conditioned by these “ruling ideas” to think that private property is an important freedom, even a “human right,” and that competition and money-making greed are “natural” human traits. We might even think we live in a society that is free because, say, no law stops us from doing what we want much of the time, or that people in our society are equal because all have the same rights under the law. In fact, Marx and Engels suggest our freedom is empty. As a worker, you lack the resources to live a truly fulfilling life and you spend most of your time being controlled by the bourgeoisie, who exploit your labour for their own profit. Nor are you in any meaningful way equal to the capitalists. They have far more power and wealth than you, and the law systematically favours their interests, not yours.

Ideology thus masks relations of domination and subordination, disguising those relations in languages of justice, nature, and necessity. And if ideology is a false belief that props up unjust social arrangements – the domination of the ruling groups over the rest – then there seems to be little point in studying ideology in depth. Wouldn’t we be better off focusing our attention on understanding those relationships of domination and how to change them? As Marx famously asserted: “philosophers have merely interpreted the world; the point, however, is to change it” (Marx, 1888).

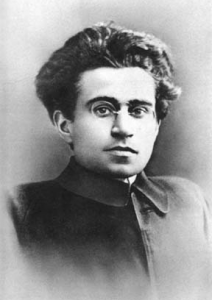

Scholars of ideology who work in the Marxist tradition remain fascinated by the mechanisms our society uses to get people to accept its structures and norms such that they seem normal, necessary, and maybe even natural. However, they tend not to share Marx’s (early) view that those mechanisms are ephemera best set aside by clear-eyed analysts. The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), who was less confident than Marx and Engels that ideas are of secondary importance to economic relationships, used the term “hegemony” to describe a belief system that is so dominant that alternative ways of thinking are almost inconceivable. Capitalism becomes a truly hegemonic system when people overwhelmingly see its way of doing things as “common sense.” For Gramsci, such hegemonic beliefs are reproduced by all sorts of social mechanisms. Teachers, thinkers and journalists propagate them and influence others to believe in them; but so, we may infer, do less obvious sources such as movies, novels, music, churches, and the family. Gramsci was interested in counter-hegemony: how to get people to think and act differently? Meaningful change could be fostered, in part, by changing how people think.

Later thinkers within the rich and complex scholarly traditions known as “Western Marxism” and “Critical Theory” have explored the ways in which support for capitalism is generated through the institutions, psychology, practices, and discourses of daily life (see Leopold, 2015 and McNay, 2015), usually with an eye to the possibility of radical resistance. Common to these traditions is the conviction that capitalist market economies are faulty ways of organizing our affairs. We would do better to challenge, destabilize, and (hopefully) transcend this economic system and its cognate political and social structures, replacing them with something else. (What might that be? See chs. 5, 6, and 12 in the present book for some ideas). But writers in these traditions have become gradually less certain that ideology is something we can leave behind. Perhaps a society freed of exploitation and domination (assuming this to be possible) would still need “ideology” in the sense of a widely shared set of beliefs that help to make the society run. Those beliefs, however, would no longer be geared to propping up an unjust set of social arrangements – surely a great gain, if it could be achieved (e.g., Leopold, 2013).