Introduction

Kyle Jackson and Joy L. K. Pachuau

James Herbert Lorrain was one of the most significant missionaries and linguists to operate in the Indo-Burma borderlands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His Logbook—a record spanning four decades and some 147 handwritten pages—contains descriptions of his everyday experiences as well as interactions with local people, from his arrival in Bengal in 1890 to his departure in 1932 from the Lushai Hills District (today: Mizoram).[1] The Logbook preserves shorter summaries of the newsy letters Lorrain sent home to his parents, as well as to associates at the Baptist Missionary Society (BMS) and beyond. For Lorrain (or Pu Buanga, “Mr. Blond,” as he is known in the Mizo language), the Logbook thus represented a second, if partial, record of his time in Northeast India were his memories to fade or posted letters to go astray. Today, the original letters are seemingly lost to the historical record. Only the Logbook remains.

That the Logbook was never intended for a public audience makes it a particularly valuable resource for students of history: It is comparatively free from the strategic self-censorship and self-consciousness incentivized by official mission reports, funding letters, and other public records. An example of what historian Collette Sirat calls “personal writing,” the Logbook was produced by someone in a “familiar environment [and] writing for themselves.”[2]

But despite being one of the most important written sources in the early colonial history of Mizoram, the Logbook has until now been relatively inaccessible, the original available only for in-person consultation at the Angus Library and Archives at Regent’s Park College (Oxford). Issues of access for distant researchers are compounded by other inequalities, including what sociologists call the “global mobility divide”.[3] At the same time, existing physical reproductions available in India have introduced complications of their own. One facsimile known to the authors is a photographed copy of a xeroxed copy of a handwritten copy of the original! And while a handful of other primary source collections on the wider region’s history do exist, these are published commercially in physical formats by regional presses. The memoirs of colonial administrators, such books tend to spotlight the same sorts of agents who wrote them, offering carefully curated and top-down perspectives that often left little room for local voices.

Though the perspectives and experiences of diverse local peoples (for instance, Lushai, Kuki, Chin, Mru, Chakma, Mara, Lai, Naga, Assamese, and Bengali) remain mediated to varying extents, the Logbook is unique in recording much of what local peoples said and did during important moments in decades prior to mass alphabetic literacy in the region. It contains vivid descriptions about how local historical actors in this era were savvy knowledge brokers, go-betweens, translators, performers, dreamers, and experimenters. It reveals how a range of colonized peoples navigated complex processes of colonial modernity, even as they were barred from equal membership within it. In today’s era of increasingly complex contact between the Northeast and the rest of India, the need to challenge enduring stereotypes about the region—especially its supposed primitivism, remoteness, historical stasis, and exclusion from urban history—is more urgent than ever. The Logbook offers current and future generations of students some critical raw materials for doing just that.

As a primary source transcription and online educational resource (OER) for Northeast India, Lorrain’s Logbook: Notes from a Missionary to Mizoram, Northeast India (1891-1936) aims to “expand the archive.”[4] Lorrain’s historical observations are decades deep, encompassing a wide range of fields: From notes on labour and clothing to comments on climate and prices, and from observations of non-human life-forms to remarks on historical linguistics, the source certainly emphasizes, but also goes far beyond, Lorrain’s evangelical concerns. It is an invaluable record to students of history in and of the region.

This Introduction to Lorrain’s Logbook aims to provide students and scholars with some tools for thinking about and using this primary source. A first section (§I) briefly sketches the wider contexts of missionization in Northeast India. We then turn to Lorrain (§II) and his Logbook (§III), and the ways in which this primary source can be used not only to reconstruct history but also for developing new questions. The fourth part of this Introduction considers materiality (§IV): Much is gained, but what is lost with the digital transcription of an original source? The essay closes (§V) with technical notes on the transcription, as well as practical advice on how to use and further contextualize the Logbook.

I. Wider contexts of missionization

Lorrain’s brand of evangelism was nothing new. His work followed in the footsteps of various Nonconformist denominations in Europe—people who were profoundly moved and prompted by the felt need to proclaim and to make known to the world their ideas about God’s love. Such movements began with the Pietist movement in northern Europe in the seventeenth century and stretched through to the Nonconformist evangelicals of Britain, whose missionaries spread across the globe in territories colonized and beyond. But these movements cannot be seen as a homogenous category: they had evolved and undergone several changes in organization, emphases, affiliations, and compulsions. Their commonality, however, was framed by the Protestant movement led by Martin Luther, which drastically changed the nature and understanding of Christian doctrine and devotion. Going beyond the Reformation ideal of making scripture available in local languages, the Pietists took it a step further, stressing their felt need to make alphabetic literacy and numeracy universal.[5]

The Nonconformists were also tied together by a religious zeal that enabled them to endure a range of material, emotional, and physical hardships. A self-styled spirit of adventure and discovery, as well as interest in the newly developing fields of anthropology, linguistics, biomedicine, and the natural sciences, seem to have been their portion too—not unlike what has been written of administrator-ethnographers in many frontier zones.[6] In India, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg and his friend Heinrich Plütschau were the first of the Pietist missionaries to arrive, establishing themselves in the Danish colony of Tranquebar (Tarangambadi) in Tamil Nadu in 1706. Beyond their desire for the spread of Christianity, their allied work of translation and providing access to education in local languages to all sections of society is well-known. Moving away from an earlier tradition wherein the Bible was presented in synoptic or paraphrased forms, the Pietists were interested in translating the Bible word for word. They were likewise deeply involved in trying to understand the environmental and political worlds around them. In their view, the ‘Book of nature’ was as important as the ‘Book of Grace’ (the Bible) for understanding how God worked in the world. Experiments such as the ‘cabinet of wonders’—with the aim of showcasing new ‘discoveries’—became an important aspect of their Christian endeavour, and descriptions and artifacts of all kinds were sent back to Europe.[7]

II. Who was J. H. Lorrain?

Lorrain and his close friend Frederick William Savidge (whose association with the Lushai Hills was as deep and enduring as Lorrain’s) belonged to a similar category of missionaries. Evangelical work did not merely mean presenting the Gospel to the ‘heathens.’ Instead, they followed the example of their predecessors and peers by emphasizing converts’ introduction to the world of colonial modernity. Converts were to be provided with the tools to participate in colonial modernity by making their faith a tool of self-transformation. While neither Lorrain or Savidge authored ethnographic studies, their constant touring, in addition to their work on grammars, dictionaries, and the Logbook itself, makes it clear that understanding and recording the cultures of local peoples was very important to them.

The mission to the Lushai Hills was not the first foray of Christian missionaries to Northeast India. Through the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the region came to be heavily evangelized. Except for present-day Arunachal Pradesh, the region hosted different mission groups with differing theological and missional practices. The missions were not always successful, according to their own benchmarks, as in the cases of the Serampore mission (early nineteenth century) and the Roman Catholic mission of the mid-nineteenth century. Working among the Nagas, the American Baptists attracted significantly more local interest, as did the Roman Catholic mission of the late nineteenth century, and the Welsh Presbyterians (Calvinistic Methodists), whose mission took them to the Khasis and Jaintias (in present day Meghalaya) and to the Lushais (Mizos).[8] Today, however, many more denominations exist (Salvation Army, Pentecostalists, Lutherans, Seventh Day Adventists, to name a few) whose members tend to be converts from other, more established denominations.

Lorrain and Savidge made attempts to enter the Lushai Hills well before the district came under total control of the British. These initial attempts failed. When in 1894 they were able to enter the Lushai Hills, Lorrain was only twenty-two years of age, and Savidge ten years older. Lorrain seems to have been the one with more initiative; he, for instance, had enrolled them both for mission work in the first place. Lorrain—the more prolific of the two—also has a larger archival presence. Their lengthy stay in the Lushai Hills unfolded in two stages, the first lasting from 1894 to 1899 (in Aijal/Aizawl), under an independent mission known as the Arthington Aborigines Mission; the second stint was from 1903 to 1932 (in Lungleh/Lunglei) under the Baptist Mission Society of London, with Savidge retiring in 1925.

The work of a missionary required more than spiritual proclivities. In fact, neither Lorrain nor Savidge were theologically trained: Savidge was a professional photographer with a studio in Ely, London, while Lorrain was trained as a telegraph communicator, having worked briefly at a Post Office in Holborn, London, prior to becoming a missionary. Missionary work required them to be versatile, and both moulded themselves according to the needs of the hour. This included learning an oral language and assisting in the construction of a workable script and orthographical system—not easy tasks. Prior to their venture into the Lushai Hills, they had spent time in Bengal and amongst the Abors (Adi) of Arunachal Pradesh, becoming proficient in both languages.

In the Lushai Hills, Lorrain and Savidge decided to adopt the Roman script and the ‘Hunterian’ system of orthography. Working from countless interactions with local peoples, and benefiting considerably from local linguistic expertise, they published a Lushai-English dictionary of more than 7,000 words not long after their arrival, along with a basic Lushai grammar in 1897. Lorrain would later bring out a more complete dictionary (of over 30,000 words) in 1939—his dedication to the project evident in how he remained in Calcutta for three years after his retirement in 1932 to see its completion. Proficient in Hebrew and Greek, Lorrain also played a significant role in the gradual translation into Mizo of the books of the Bible. And both Lorrain and Savidge enriched the literature of the Mizo people through the composition and translation of Christian literature in Mizo (Pilgrim’s Progress, Spurgeon’s Sermons, etc.), the creation of texts for newly established schools (from Aesop’s Fables to geometry textbooks), and the translation of hymns.[9]

Missionary presence in the Lushai Hills lasted less than a hundred years. Today, despite it being more than fifty years since the last of the foreign missionaries departed Mizoram, the Mizos have generally not been antagonistic to the work of the missionaries—this despite the burgeoning criticism of colonial missionaries’ work elsewhere. Similar to the Dalit theology that has emerged in other parts of the country, Mizo Christian theologians have aimed to re-interpret and understand the nature of Christianity and conversion from within local and nativistic frames.[10] But as to the historical missionaries themselves, the overarching narrative remains a sense of deep regard and respect. Such feelings do not differ from the ‘Raj nostalgia’ evinced and articulated by ethnic minorities at the time of independence for colonial rule and its officials, according to historian David Zou.[11] A large part of such an attitude perhaps stemmed from the fact that the two main mission agencies—the Welsh Calvinist Methodists (Presbyterians) and the Baptists—consistently worked together through what was called the ‘comity arrangements.’ Adopted in the Lushai Hills and elsewhere, such an approach to missionization brought a geographically broad sense of unity and purpose, a consciousness of identity connected to, but expanding beyond, an earlier, more fractured landscape. Missionary efforts to push forward literacy, knowledge, and education in the faith, as well in the knowledge systems of the wider-world, significantly contributed to the making of the Mizo people—something that perhaps continues to be recognized and acknowledged in the region. Moreover, the long tenures of missionaries—some lasting several decades—coupled with their intensive touring of the region (and the relationships thus cultivated), paved the way for longstanding associations, multi-generational relationships, and connections across space.

While Lorrain and Savidge’s work in the Lushai Hills was generally well-regarded, loved, recognized, and respected by those in the region itself, one suspects that the missionaries’ return to their home country was not always easy. Many European missionaries remained in India for several decades (in the case of Lorrain it was four). They returned to their home country changed, and to changed circumstances. While they were often regarded with deep respect in the lands of their missions,[12] they retired to lives of relative anonymity upon their return. One can imagine that the contrast in their receptions would have been difficult to bear. And for missionaries who returned to Europe after the Second World War, the decline of the imperial project itself, alongside the fundamental questioning of religion and its role in an increasingly secularizing society in Europe, led some missionaries to question their faith and their role in the enterprise.[13] Not much has been written about missionary lives post-return to their home countries, but Lorrain—who lived only for another twelve years (d. 1944) after his return—seems to have spent this time systematizing the knowledge he had acquired, writing in mission journals about his work, and constantly being in touch through letters with the Mizo people he had encountered and loved. Just before he died, Lorrain was able to send greetings to the people of the Lushai Hills by posting a gramophone recording. An early and literal form of ‘voice mail,’ Lorrain’s record was played for keen audiences in the region’s two mission centres during their jubilee celebrations of Christianity’s arrival.

III. The Logbook as a source

The Logbook highlights for us Lorrain’s viewpoints, from minute details regarding initial attempts at establishing camp to the challenges of establishing a relationship with a people they knew next to nothing about. While the Logbook was written by a missionary as an account of his work and activities, thoughts and ideas, one can also glean local voices, and Indigenous ideas about the foreigners, through recorded reactions to the missionaries’ work. Scholars P. Thirumal, Laldinpuii, and C. Lalrozami use the Logbook to highlight local agency in linguistics, demonstrating how local men like Khamliana and Suaka were in fact vital partners in an accomplishment often solely ascribed to Lorrain: the creation of a writing system for the Mizo language.[14] The text likewise speaks to a host of historical topics both tangible (food, clothing, medicine, architecture, the materials of everyday life) and intangible (ideas, spirituality, preconceptions, humour, and emotion); at the same time, it preserves evidence of rapidly increasing local interest in Lorrain’s earliest biblical translations, providing an opportunity to explore the understudied demand—as opposed to solely the supply—side of missionization in the region. So, while the Logbook can be used to study Lorrain’s self-styled image as a “pioneer,” it also reveals the myriad ways his life fundamentally entangled with local materials, plants, and non-human animals, and even how his central religious mission—and indeed his own personal wellbeing—did not merely involve but depended upon hosts of local individuals.

Historian John Thornton argues that the general, nineteenth-century Christian missionary predisposition against Indigenous religions did not necessarily preclude thorough descriptions of those religions.[15] Lorrain was no different. Globally, missionaries at the time were intensely interested in the existing traditions and thought-worlds they encountered, though primarily for their own evangelical reasons and often in a search for the “parallels” with Christian doctrines that could demonstrate not only “common humanity” but also the global breadth of God’s grace.[16] Lorrain’s biases in observing, interpreting, and recording such details can be easy to anticipate, providing a useful—and, in the case of some of his earliest observations, an exclusive—record of local spirituality and ceremony.

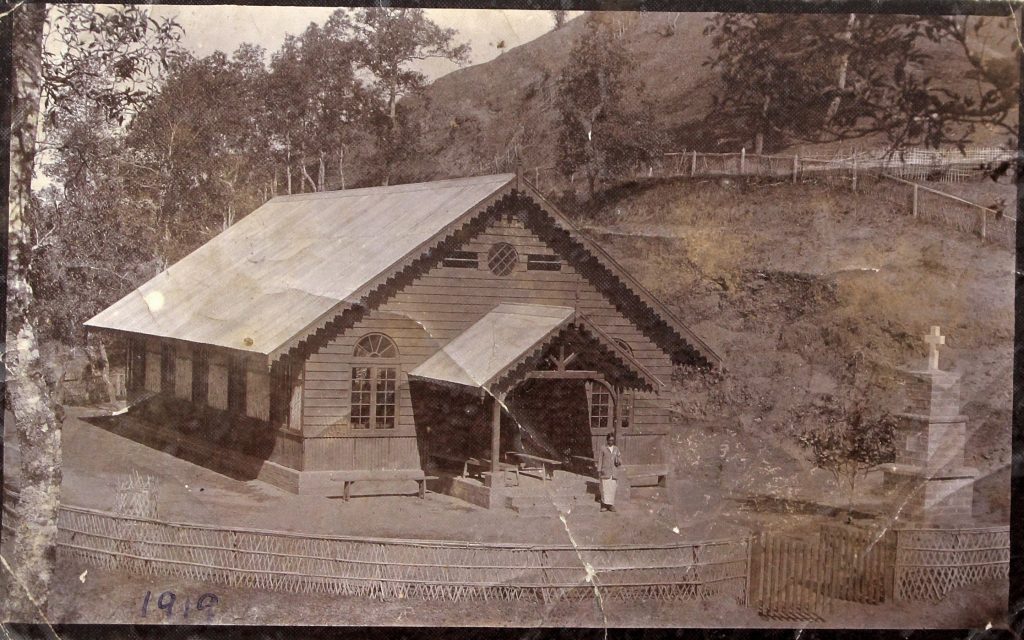

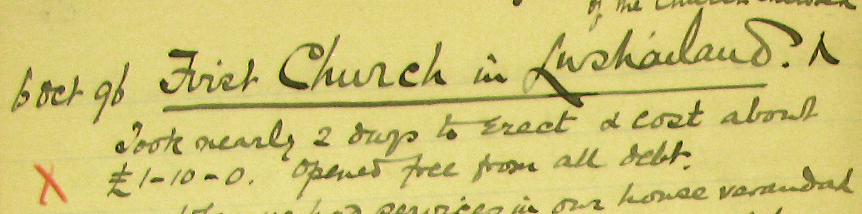

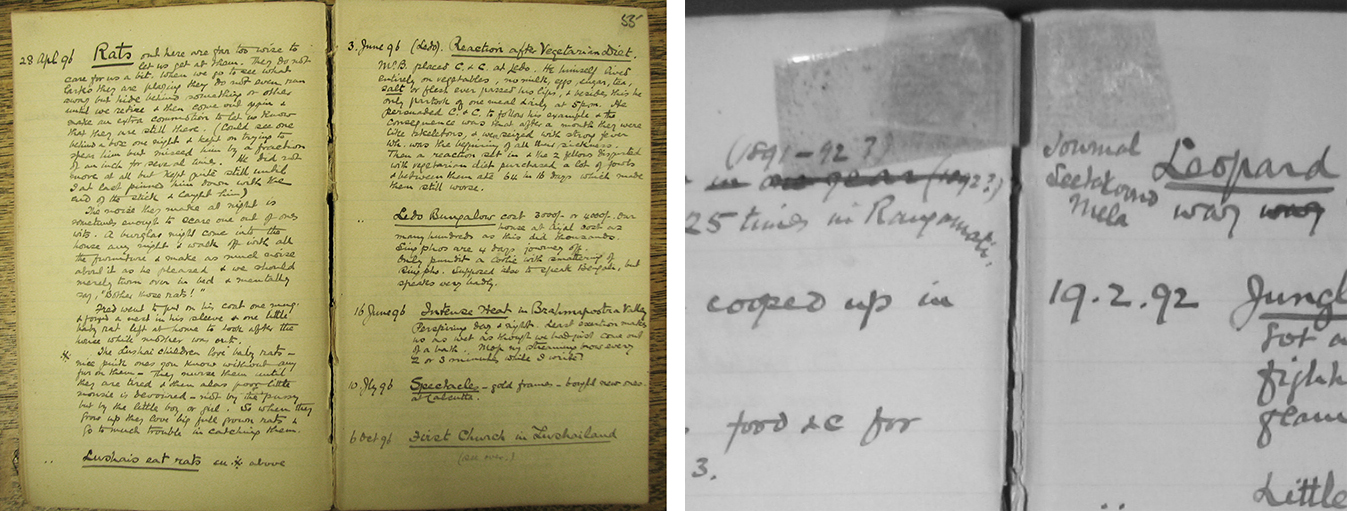

Another theme commonplace in the global paper trail of evangelism is the highlighting of “first achievements,” dates that Lorrain often emphasizes in the margins of the original Logbook by drawing “Xs” in bright, orange-red pencil crayon: the first mission house, the first convert, the first church, and so forth. In their colour, form, and sacred significance, these symbols can be read as Lorrain’s way of marking “red-letter days”—a phrase he uses explicitly in an April 1903 entry—invoking the old practice of using red letters to denote holy days in church calendars. For Lorrain and later Christians in the region, these moments came to represent the sacred first fruits in an ordained harvest of souls. Moments as heavy as these left their mark not only in the Logbook but also in the physical landscape: In 1917, for example, churches in the North Lushai Hills took up a collection to erect a towering monument to Khuma, “our first Lushai Christian” (Figure 2).[17] Another stone marker stands today in Zarkawt, a locality in Aizawl, to mark the location of Lorrain and Savidge’s first church in the region (see the related Logbook entry in 1896).

And yet historian Jean M. O’Brien reminds us that such narratives of “firsting” need also to be approached reflexively and critically. They can paint pictures that foreground only Europeans as “the first people to erect the proper institutions of a social order worthy of notice.”[18] Without minimizing the significance of these moments for Lorrain—a valid research topic in itself—nor the genuine emotional power these events still carry for many Christians in the region today, O’Brien asks students of history to also remain attentive to how discourses of “firsting” orient focus, highlighting what is “worthy of notice” in ways potentially dispossessive. In her own study of narrative “firsting,” historian Lauryn Beck reminds us that colonized “peoples […] experienced firsts just as much as Europeans did.”[19] Lorrain’s “red-letter days” are not the neutral or authoritative markers of history they are sometimes made out to be. We might instead ask: How did ideas of gender, race, and class, for example, impact the character of how these firsts played out and were documented? What exactly did these firsts mean, to whom, when, and why? What is their function today?

IV. The costs of digitization

Scholar Paul Duguid tells a story about a Portuguese archive in which he encountered a researcher behaving bizarrely.[20] Instead of slowly reading through a collection of eighteenth-century letters, the researcher was energetically sniffing them, pausing only to note an occasional date and place of writing. Mystified, Daguid asked the researcher what he was doing. The man replied that in the 1700s, towns affected by cholera would ensure that outward-bound letters were sprinkled with pungent vinegar—a measure to stop the spread of disease. He was using his nose to map a history of cholera outbreaks.

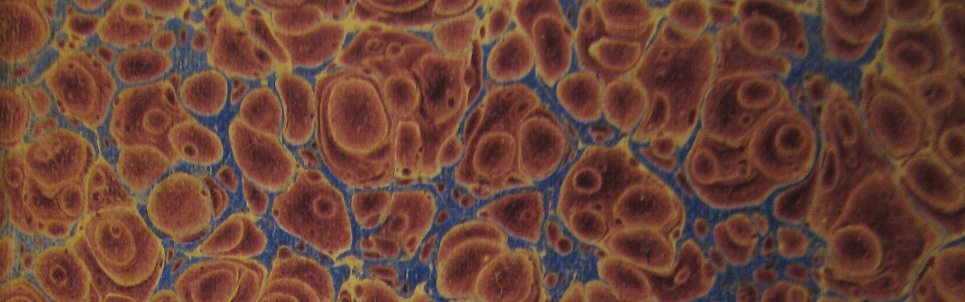

The example shows how the digitization of a physical source—a digital photograph of a letter, a transcription of a Logbook—is not merely a neutral act of “preservation”; rather, digitization implicitly delineates where a source’s value begins and ends.[21] In English, historical documents “contain, hold, carry, and convey information”—verbs evoking materiality, like the scent of vinegar preserved in a Portuguese archive.[22] In short, the digital version of Lorrain’s Logbook that follows is not a “copy” but something new, separated from what sociologist Brenda Danet calls the “physical stuff of texts – the surfaces on which they are inscribed, the materials used to do the inscribing and the aesthetic aspects of their creation and manipulation.”[23] While our transcription preserves Lorrain’s celebratory “red-letter day” markings, approximating them with pixels in the shape of an orange-red “X“, it cannot preserve the physical aspect of these markings (Figure 3), how in these moments Lorrain pressed his pencil tip into the paper firmly, leaving decided strokes and dark pigment that mirror, and even physically embody, his understanding of the weightiness of these achievements.

What is the physical stuff of the Logbook? A black vinyl cover (see Figure 1) encloses the string-bound pages of light-brown, lined paper on which Lorrain handwrote over 60,000 words in black inks, pencil leads, and orange-red pencil crayon. In person, the object feels small, a compactness conducive to transport and storage. Marbled endpages feature one-of-a-kind designs handmade by an artisan who dipped papers onto floating ink drops (Figure 4). A final section inside the Logbook bulges with ephemera cut-and-pasted by Lorrain—typewritten letters, newspaper articles, and obituaries—a material feature we have attempted to preserve in the digital version by including images of the clippings.

The Logbook also bears the marks of physical environments and age. Some of the page spreads are split at the inside joint (Figure 5, left), while the outer spine is corroded and torn open, evincing not only age but also years of opening and closing. Visible attempts, probably Lorrain’s, to repair the Logbook are an interplay between materiality and text: Where adhesive bands (Figure 5, right) hold split bindings together, nearby entries read “umbrella over me in bed” (February 1891) or remark upon significant swings in daily temperature (December 1891). The legendary humidity of Northeast India infuses the Logbook on multiple levels, from the written word to the molecular.

Finally, the material character of Lorrain’s handwriting itself conveys one of his hallmarks as a missionary: his enduring presence in the hills. Lorrain “stayed on” far longer than any other foreign missionary in the region—or indeed any British administrator. The sheer regularity of the handwriting in the Logbook, largely consistent across decades and geographies, shows little evidence of any meaningful change in writing conditions. The consistent movements of his pens, the relative lack of errors or struck text, and the careful organization indicate that the handwriting took place in predictable places and on clean, flat writing surfaces. For the most part, these were not entries scribbled on the go, on a lap, or in a hurry.[24] Things change only towards the end of the notebook, where Lorrain crams more than forty tiny lines of handwriting to a page, compared to the twenty-seven typical of earlier, roomier entries. This, we believe, also comes down to materiality: Paper is running out. In such sections, our transcribers sometimes had difficulty deciphering the prose, resulting in one of the few digital artifacts from the Logbook’s physical form: parenthetical notes that read “illegible.”

Given that the Logbook was physically written in Northeast India, our digitization project can be viewed in some measure as an act of its partial repatriation, if only in virtual form.[25] When Lorrain departed the Lushai Hills, the Logbook probably followed a typical route out of the region, first powered on roads by the muscles of humans or oxen, then over the waters of the Tlawng and Barak rivers by the tightening sinews of Bengali boatmen. Coal-fire would have driven it down the Brahmaputra River to the Goalundo terminus of the Eastern Bengal State Railway, from where it would have travelled southwestward to the port of Calcutta and, later, beyond. Abstracted to crude lines, this is horizontal travel across some 8,000 kilometres and a vertical descent of some 700 metres, to an eventual below-ground storage room in the Angus Library and Archive, in which the Logbook has sat undisturbed save for the rare research request or a slight, one-in-a-generation earthquake (1986). And yet, as this section has shown, the Logbook is first a thing in this world. We acknowledge that the “accessible and open” transcription that follows unfortunately keeps much—material qualities, physical environments, and even certain research questions—inaccessible and closed.

V. Notes on the transcription

Our transcribers have tried to create as accurate and precise a transcription of the original text as possible, with only minimal annotations. If the Logbook punctuates incorrectly, the transcription does also. Square brackets signal an editorial intervention: While the parenthetical note (sic) means that Lorrain is signalling a grammatical error, [sic] means that the transcription editors are signalling Lorrain’s error. The text appears essentially as-is in the original, save for two racial slurs omitted under our guiding principle of doing no further harm; here we also follow current practices in archival studies by linking to scholarship on the wider history of racism and traumatic text, as well as relevant scholarship authored by members of the communities who the terminology disparaged.[26]

The formatting of the digital version of the Logbook gestures towards the original, imitating the original indentations and other non-textual markings. Drawings are preserved in image form. Our version is divided into two parts. Part 1 (1891-1897) is a straight-forward year-by-year account, while Part 2 (1903-36) includes entries recorded after Lorrain returned from furlough in Britain to the Lushai Hills, a distinction he also makes explicit in the original text. In the latter section, Lorrain pays less attention to precise chronology, and pastes scrapbook materials towards the end of the notebook. While we have introduced these two overarching sections to provide structure to the OER, the entries themselves appear sequentially and verbatim, with fidelity to the original.

Publishing a record that Lorrain did not intend the world to see brings up complex issues of consent. Lorrain himself was aware of this problem, recording a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem about how documents can outlive authors (Logbook section: 1930-36):

“Lives of great men all remind us

As these pages o’er we turn.

That we’re apt to leave behind us,

Letters that we ought to burn.”

While our publication respects the formal rules of copyright, and while we have received permission, for example, to publish Lorrain’s photograph as a cover image for this OER, we are mindful that we cannot receive Lorrain’s permission to disseminate his notes so widely, a dilemma rarely remarked upon but common to many digital repositories of history.

Doing so also elevates this source into a new prominence. We anticipate that it will join the records of early colonial administrators in historiographical visibility, not only because of its vivid detail but also simply because of its availability. Recent scholarship on digital history tracks the “growing tendency among researchers to expect that informational resources will be available online” and to ignore sources that are not.[27] The National Archives of Australia, for example, has digitized and made accessible online just two percent of its holdings. But this tiny slice nevertheless enjoys the same overall consultation as the entirety of the physical collection.[28] While our OER gives the Logbook a new and user-friendly digital afterlife, we also encourage you to consider the spotlighting nature of digital transcription.

This is particularly important because the Logbook provides just one perspective, and from a person who eventually enjoyed relative power and prominence. One entry, for example, records the boyhood memory of a Lushai man called Zakhama, who recalled witnessing a moment of compassion during the British invasion of the hills decades prior, when Col. John Shakespear had guarded and fed a group of elderly individuals and several other people with disabilities, all of them abandoned after a battle. Lorrain documents “Shakespear’s Kindness” (section 1919-1929)—but not the reason these vulnerable individuals were left behind in the first place. The rest of the villagers at Chhipphir had run for their lives, fleeing the violence unleashed by Shakespear’s army, leaving people with less mobility behind. In fact, the shocking brutality that immediately preceded Lorrain’s tenure in the hills is almost entirely absent from the Logbook, save for a brief 1895 reference to cultural disruption: Years of warfare had so fully dislocated regular village life that traditional Lushai sports and games were on the verge of being forever forgotten. The Logbook is almost silent on the shadow of violence over the land.[29]

And so we encourage you to explore this invaluable primary source in its new and text-searchable format, but also to seek out other materials—in oral, visual, archaeological, ecological, digital, and physical forms—to illuminate it more fully. The Mizo-language newspaper Mizo leh Vai Chanchinbu (digitized by Aizawl Theological College) represents one starting point, as do the multilingual collections available online through the Endangered Archives Programme or the Further Reading section of this OER, which highlights a range of physical and e-books to explore. Lorrain’s Logbook represents a complex bundle of assumptions, preconceptions, and gaps that needs to be assessed and disentangled with care and a critical eye, even as it offers much of interest to a wide range of historical fields.

Focus questions for students

- How does Lorrain’s tone, as well as the topics he deems worthy of recording in his Logbook, change across time? What stays the same?

- The lone “pioneer missionary on the frontier” is a trope of sorts in the history of Christian missions. Can you “read against the grain” to find evidence of the agency of local people or lay Christians in Lorrain’s Logbook? How would you characterize this agency?

- It is often implied that “history” refers to human history. But life on this planet is interconnected. How does Lorrain’s Logbook reveal the connected histories of human and non-human life?

- Emotions do not only suffuse the human experience of history, but also shape how history itself unfolds. What evidence can you find of Lorrain’s emotional life? How do emotions shape Lorrain’s world? How do they shape his curation of the Logbook itself?

- As a missionary, Lorrain is fundamentally concerned with beliefs, Christian and otherwise. How does he characterize these various beliefs in his writing? Do you notice any changes in how he characterizes them over time?

- Lorrain worked extensively on Lushai-English grammars and dictionaries (e.g., 1898, 1940) and translated books from the Bible. Do you notice any trends or themes in how he uses the Lushai/Mizo language in his Logbook? What are his thoughts on the language, and are those thoughts static or dynamic?

- Lorrain assembles a scrapbook of sorts in the final section of his Logbook. How do you think that historians should interpret this material—not only the clippings that Lorrain decided to include but also the creative and physical act of scrapbooking itself?

- J. H. Lorrain, “Logbook,” BMS Acc. 250 Lorrain, Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, United Kingdom. ↵

- Colette Sirat, Writing as Handwork: A History of Handwriting in Mediterranean and Western Culture (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2006), p. 430, quoted in Elizabeth A. Lambourn, Abraham's Luggage : A Social Life of Things in the Medieval Indian Ocean World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 8. ↵

- Steffen Mau, Fabian Gülzau, Lena Laube, and Natascha Zaun, “The Global Mobility Divide: How Visa Policies Have Evolved over Time,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41.8 (2016), pp. 1192-1213. ↵

- Yasmin Saikia, "History on the Line: Beyond the Archive of Silence: Narratives of Violence of the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh," History Workshop Journal, 58 (2004), pp. 275– 87, quoted in Willem van Schendel, "A War Within a War: Mizo rebels and the Bangladesh Liberation Struggle," Modern Asian Studies, 50.1 (2016), pp. 75-117 (p. 78). ↵

- Andrew Porter, “An Overview, 1700-1914,” in Norman Etherington, ed., Missions and Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 40-63; and Robert Eric Frykenberg, Christianity in India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). ↵

- Angma Dey Jhala, An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma and Bangladesh (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019). ↵

- Frykenberg, Christianity, pp. 146-9. Also see the seventy-two cultural objects deposited by Lorrain at the British Museum between 1899 and 1924. ↵

- F. S. Downs, History of Christianity in India: North East India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Bangalore: Church History Association of India, 1992). ↵

- P. L. Lianzuala, Zofate Chanchin Tha Rawn Hlantute (Lunglei, Mizoram: Joseph Lalhlimpuia, 2012). ↵

- See, for example: Lalsawma, Revivals: the Mizo Way (Aizawl: Lalawma, 1994); Vanlalchhuanawma, Christianity and Subaltern Culture. Revival Movement as a Cultural Response to Westernization in Mizoram (New Delhi: ISPCK, 2007); and Zolawma, “A Critical Assessment of the WCC’s Study Project on ‘Ecclesiology and Ethics’ from a Tribal Perspective,” Mizoram Theological Journal, 8.1 (2008), pp. 14-44. ↵

- David Vumlallian Zou, “Vai phobia to Raj nostalgia: Sahibs, chiefs and commoners in colonial Lushai Hills,” in Lipokmar Dzüvichü and Manjeet Baruah, eds., Modern Practices in North East India: History, Culture, Representation (New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 119–43. ↵

- Savidge was said to have received over 2,000 letters from people in the Lushai Hills from the time he retired in 1925 to his death in 1934, showcasing people’s affection for him—and a fact made more exceptional by the relative financial poverty of the people and the difficulties in communication; see Lianzuala, Zofate Chanchin, p. 368. ↵

- Joy L. K. Pachuau's interview with the spouse of a well-known Welsh missionary in the Lushai Hills. ↵

- P. Thirumal, Laldinpuii, and C. Lalrozami, Modern Mizoram: History, Culture, Poetics (New York: Routledge, 2019), pp. 49-54 (esp. pp. 49-50). On Khamliana, see Lalhmingliani, "Khamliana," Historical Journal Mizoram, 12 (2011), pp. 1-11, and Kyle Jackson, "A chief and his wheelbarrow: Digitisation and history in India’s Northeast," 4 November 2014, Endangered Archives Blog, British Library, London, https://blogs.bl.uk/en dangeredarchives/2014/11/mizoram.html, accessed 4 March 2023. ↵

- See John Thornton, "European Documents and African History," in John Edward Philips, ed., Writing African History (Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2005), pp. 254-65. ↵

- Bronwen Douglas, “Encounters with the Enemy? Academic Readings of Missionary Narratives on Melanesians,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 43.1 (2001), pp. 37-64 (p. 43). ↵

- F. J. Sandy, "Chief matters dealt with at the North Lushai Presbytery, Sept 20-24, 1917," National Library of Wales, CMA 37 335, p. 1. ↵

- Jean M. O'Brien, Firsting and Lasting : Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), p. vii. ↵

- Lauren Beck, "Introduction" in Lauren Beck, ed., Firsting in the early-modern Atlantic world (New York: Routledge, 2020), p. 1-22 (p. 3). Also see Kyle Jackson, The Mizo Discovery of the British Raj: Empire and Religion in Mizoram, Northeast India (1890-1920) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). ↵

- John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000), 173-4. ↵

- Brown and Duguid, The Social Life, p. 189. ↵

- Brown and Duguid, The Social Life, p. 184. ↵

- Charles Jeurgens, “The Scent of the Digital Archive - Dilemmas with Archive Digitisation,” BMGN - Low Countries Historical Review, 128.4 (2013), pp. 30-54 (p. 34); and Brenda Danet, “Books, Letters, Documents: The Changing Aesthetics of Texts in Late Print Culture,” Journal of Material Culture, 2.1 (1997), pp. 5-38 (pp. 5-6), quoted in Lambourn, Abraham's Luggage, p. 243. ↵

- Sirat, Writing as Handwork, p. 430. ↵

- Librarian Todd Michelson-Ambelang highlights “the cultural importance of ownership” of historical sources, even in digitized forms; Todd Michelson-Ambelang, "Our Libraries Are Colonial Archives: South Asian Collections in Western and Global North Libraries," South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 45.2 (2022), pp. 236-49 (p. 247). On the repatriation of a facsimile of another set of sources from Oxford to Northeast India, see Arkotong Longkumer, “'Lines that speak': The Gaidinliu notebooks as language, prophecy, and textuality," HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 6.2 (2016), pp. 123-147. ↵

- Kate Holterhoof, “From Disclaimer to Critique: Race and the Digital Image Archivist,” Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11.3 (2017). ↵

- Jeurgens, "The Scent," p. 45. ↵

- Adrian Cunningham, "The Postcustodial Archive," in Jennie Hill, ed., The Future of Archives and Recordkeeping: A Reader (London: Facet Publishing, 2011), pp. 173-189 (p. 182), quoted in Jeurgens, “The Scent,” p. 45. ↵

- See Joy L. K. Pachuau and Willem van Schendel, The Camera as Witness: A Social History of Mizoram, Northeast India (Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2015), chapter 6; and Jackson, The Mizo Discovery, chapter 1. ↵