2 Making Implicit Expectations Explicit

As educators, we have spent much of our lives in classroom cultures, both as students and as instructors. Over time, without even realizing it, this has given us a status of academic culture insiders. The expectations of our academic and disciplinary cultures have become second nature.

Many of our students, however, experience our academic culture as outsiders. This can be true of students whose previous education took place outside of Canada, but also true of many other groups that may feel traditionally alienated from academic culture. This group may include first generation students, Indigenous students, and adult learners returning to postsecondary education. Facilitating inclusion and equal participation for these students involves two strategies (1) shifting the classroom environment to make space for the contributions that our students offer, and (2) making the implicit expectations of the classroom explicit to students. This second strategy is an often-neglected pillar that avoid the disconnection that contributes to academic difficulties (Blasco, 2015).

A key skill to increase support and inclusion is identifying tacit, implicit knowledges and making them explicit for students. This is a challenging task for educators for two reasons:

- We have reached “expert” status in learning how to learn within the context of a particular education system.

- We have reached “expert” status in learning to think, read, write, and problem solve within our disciplines.

Implicit Knowledge about Academic Systems

We have tacit, unspoken knowledge about how academic systems work. This includes knowledge about how to relate and communicate in a classroom (whether online or face to face), knowledge about how to approach academic texts, and knowledge about how assessment takes place. Some of these unspoken knowledges might include:

Classroom knowledge:

- How to respectfully address the instructor

- When and how to ask questions or respond with comments

- How to join an online class meeting

- How to select whether using the microphone or chat function is more appropriate at a particular point in an online class

- What an appropriate academic tone for an online forum post might be

- How to respectfully disagree with a post on an online forum

Knowledge about academic texts:

- How to identify the important focal points in an academic reading

- Where to find key information in an academic journal article

- How to distinguish between information that should be memorized and information which should be integrated and applied

- How to organize an academic text in a particular class (consider the differences between a lab report, a history essay, and a business report)

- How to distinguish between formal and informal language use

Knowledge about how assessment takes place

- How courses with continuous assessment are paced over the course of a semester

- How to approach a course syllabus and extract information about key assignments

- What different assessment types (e.g. report, oral presentation, group project) might typically involve

Often, the knowledges listed above, and others, remain unexplained within the class. Students may assume that others already are familiar with the expectations, and are unaware that many of their peers are also in the same place on their journey. Students may feel hesitant to ask clarifying questions, or they may assume that the expectations from their previous educational experiences will also be true for their current learning. As a result, students who have the skills, abilities, and desire to succeed may fall short of expectations, largely because of unawareness.

In addition to knowledge about academic systems, we also carry discipline-specific knowledge and procedures, that while new to us earlier in our academic careers, have now become embedded within our ways of thinking and communicating. These knowledges, sometimes known as academic literacies (Lea and Street, 1998), go beyond reading and writing skills, and concern the ways that information is organized and presented, and the ways that problems are solved within a discipline.Implicit Knowledge: Disciplinary Thinking

The Decoding the Disciplines approach (Middendorf and Shopkow, 2018) provides one method for decoding some of the implicit knowledges. When these knowledges remain implicit, they can create learning bottlenecks for students. Bottlenecks, as defined by Middendorf and Shopkow, are areas in a course where a high percentage of students struggle to meet a particular learning outcome. These bottlenecks are common and frequent, central and foundational to the learning in the course, and often aggravating for educators to continually manage.

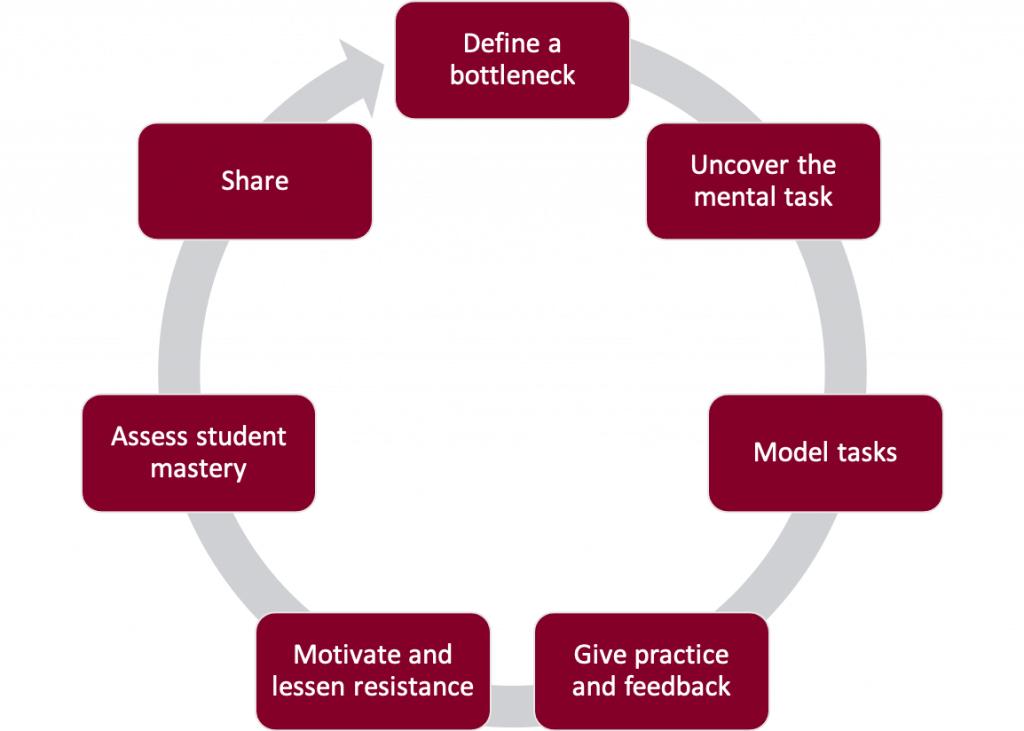

The Decoding the Disciplines model moves through a seven step cycle:

Define the Bottleneck

The first step in addressing a bottleneck is to ensure that it is defined precisely. For example, a statement like, “students’ portfolios list experience without reflection” is likely too general to identify and support a specific thinking and writing task. A more specific statement such as “students do not yet understand that reflective writing combines evidence with personal reflection on its significance and meaning for their future work” is likely to be of more help.

Uncover the Mental Task

Perhaps the most challenging step in addressing bottlenecks is uncovering the mental processes that a proficient expert uses to address the task. This step involves breaking down the task into its smallest component steps, thinking out loud to be able to directly explain a task that is typically intuitive and automatic to experts. This step involves two key questions:

- What are the specific steps in this process?

- Why do you do each step?

Because this process is inherently challenging, it is often helpful to work alongside a colleague outside of your discipline who can help in uncovering assumptions and identifying gaps between your thinking process and how you currently articulate that process to others. For example, your colleague could try to follow your verbal or written directions (e.g., assignment guidelines) to complete a task, and identify the points that are unclear. Through the process, a colleague can continue to ask questions and summarize, providing you with clearer knowledge of what might need to be more explicit to a novice learner.

Example:

- Critically reading research articles

- Taking notes

- Paraphrasing key information

- Integrating key information into a longer argument

- How I read the abstract and keywords to determine if the article is relevant to my research.

- The process I use to skim a literature review, and how I identify additional sources I may want to review. Because I observe that many students do not yet understand the purpose of a literature review, I would highlight that this portion of the article provides background knowledge about what is known about the topic, but that it does not reflect the main findings of the research that will be described in the article.

- The way I skim the methods section to gain basic information about how the study is conducted. At this stage, depending on the level of the students’ course, I will mention to students that they will encounter unfamiliar terminology, and that their goal should be to gain a broad understanding without becoming stuck on specific research terms.

- I will highlight the way that I carefully read the results and discussion, taking notes on key points. I might also model specific annotation strategies that my students may find helpful.

Give Practice and Feedback

After modelling the task, the next step is to provide a practice exercise for students. Break larger tasks into smaller subtasks, and provide formative feedback on the students’ work. Examples of practice tasks might be a thesis statement design exercise, an executive summary development task, or practice on a single section of a lab report. In my example of the article reading task, after completing the modelling exercise in class, my next step might be to assign students a reading exercise where they read an assigned research article following a list of guided reading questions, take notes on what they believe to be the key information in the article, and receive formative feedback on the quality of their notes and the accuracy with which they identified key information.

Address Emotional and Developmental Bottlenecks

In addition to skill-related bottlenecks, bottlenecks can also arise from emotional and developmental factors. Emotional bottlenecks can include students’ worry about a course that they have been repeatedly told is difficult, leading to anxiety about their performance, or a value conflict between the course material and students’ personal or community beliefs. Developmental bottlenecks common to students who are early in their postsecondary education include a tendency towards polarized thinking and difficulty including multiple perspectives (Evans et al., 1998). Possible strategies to address these bottlenecks include regular opportunities for reflective writing, and a practice of celebrating small successes throughout the course.

Assess Mastery

At this stage in the process, students build back up from the smaller practice tasks they have completed in their learning journey towards a final product. The tasks that were previously broken down, and the formative assessment that students received are now integrated into the larger project. As tasks are integrated, students are assessed on their ability to complete the full project.

Share

The final step in the journey is to share learning with other colleagues. When multiple colleagues in disciplinary teams work through this process on different bottlenecks, faculty teams can develop a rich collection of shared pedagogical resources that can effectively support student learning through bottlenecks.

References

Blasco, M. (2015). Making the tacit explicit: rethinking culturally inclusive pedagogy in international student academic adaptation. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2014.922120

Evans, N. J., Forney, D. S., & Guido-DiBrito, F. (1998). Student development in college: Theory, research, and practice (1st ed). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

Middendorf, J. K., & Shopkow, L. (2018). Overcoming student learning bottlenecks: Decode the critical thinking of your discipline (First edition). Stylus.