12 Tools to Develop Your Own Wisdom

Brad C. Anderson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn the following.

- The challenges of developing wisdom

- A wisdom-oriented mindset

- How to get the best out of your experience

- The importance of good mentors

- How to maintain a useful reflection journal

- Ways to build social and emotional intelligence

Wisdom is action-oriented. If you wish to develop your wisdom, then you must make an effort to do so. This chapter presents ways you may begin this process. It starts with a discussion of the challenges of developing wisdom. It explores a mindset that will help you effectively navigate those situations calling for wisdom. It then assesses how to utilize experience, mentoring, and reflection journaling to develop your capabilities. It then considers activities you can do to build your social and emotional intelligence, including engaging with cooperative learning, taking interdisciplinary courses, and indulging in your joy of the arts.

The ideas in this chapter are based on European and North American research and intended for university students and recent graduates. Individuals operating in other cultures or at different stages of their careers may need to explore methods more meaningful for their situation.

The Challenges of Developing Wisdom

Developing wisdom is different than learning other topics. To study accounting, you learn how to construct income statements and balance sheets. Becoming a scientist requires you to learn how to perform experiments. Artists learn how to paint, and so on. Those we consider wise, however, possess not only discipline-specific skills but also social and emotional intelligence, along with specific attitudes towards themselves and the challenges they face. Wisdom is a different kind of beast to master. Before we delve into specific activities you might undertake to develop wisdom, let’s first reiterate some crucial characteristics of this attribute that Chapters 1 & 2 introduced.

What people perceive as wise depends on the specific situation they are in, influenced by their values and cultural background. So, when we speak of wisdom, we need to ask, Whose wisdom? The person I think is wise, you may consider a dangerous fool. Wisdom is subjective, varying between people, and context-dependent, varying between settings and situations. You may think a course of action is wise, but that is only your opinion.[1][2][3]

Moreover, we are unable to measure the wisdom of a choice objectively. Life happens in real-time. Once we have made a choice, we are unable to go back and try something different to compare results. We may think the decision we made was good, but we will never know what might have been had we chosen something different. No matter how wonderful the outcome of our actions, there will always exist a nagging doubt, a lingering, “What if I chose this instead of that?“[4]

Additionally, though we might gain insights and develop skills the wise rely on, wisdom is gained through cumulative experience. You will, hopefully, be wiser in ten years then you are now, and wiser still in twenty years. Wisdom is not a destination but a journey. It is not an endpoint but a process. You do not attain wisdom. You develop it.[5]

So, how can you develop your wisdom? Let’s start by looking at your mindset.

Key Takeaways

- Wisdom is context-dependent

- Wisdom cannot be objectively measured

- We gain wisdom with experience

Wisdom Starts with Your Mindset

There are several attitudes discussed below that tend toward wisdom. These include recognition of the importance of values, recognizing the power and limits of knowledge, humbleness, a willingness to act in the face of uncertainty, and appreciating the dynamic nature of our problems. Let’s first look at our attitudes towards values.

A critical insight the wise possess is an understanding of the importance of values. It is our values that drive us to action just as it is another person’s values that drive their actions. Social systems require the expression of many values to thrive. Wisdom requires recognition of the importance of those values held by others. Wisdom also requires that we become consciously aware of the values that motivate our actions and how we might balance our values against others to meet the broader needs of society.[6][7]

Do you have a strong sense of what your values are? Could you clearly articulate them to someone else? How about your job, the career you pursue, or the company that hired you? Which values was that career designed to express? Does that company pursue values compatible with your own? Those aspiring to wisdom use these types of questions to guide them to vocations where they can become champions.

In addition to understanding values, those striving for wisdom recognize the power and limits of knowledge.[8] Be curious. Become a continual learner. As a practitioner in whatever vocation you have chosen, continue developing your competencies and skills. Not only will deepening your skills enhance your ability to act, but it will also educate you on the limits of your knowledge. It takes an expert to know what they don’t know.[9]

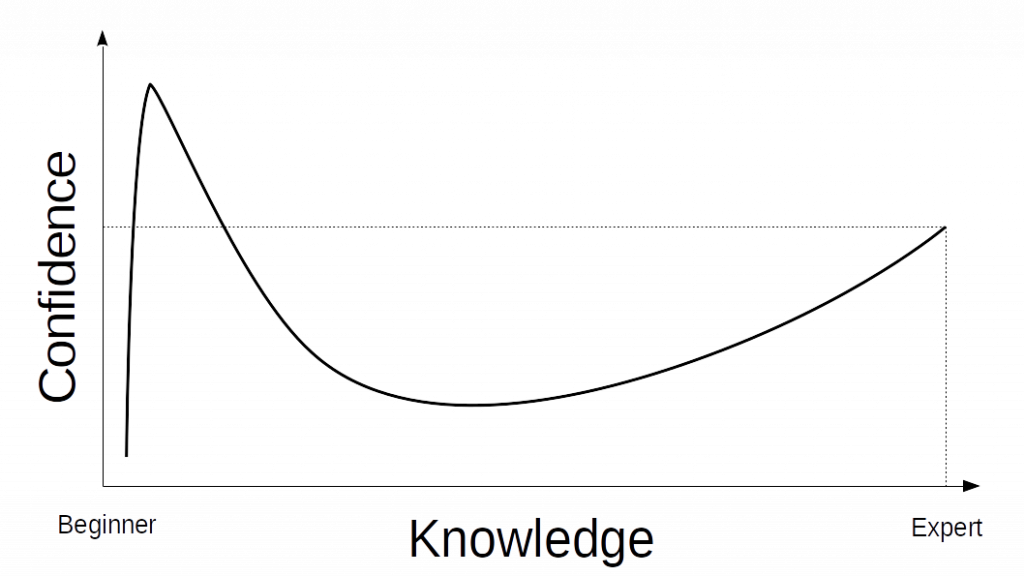

The Dunning-Kruger effect described below highlights the validity of this perspective.

Examples: The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect describes the phenomena of an individual’s level of confidence in a subject relative to their expertise. People with very little training in an area commonly possess unduly high confidence in their ability. As their training advances, they lose that confidence as they begin to recognize their limitations. With further training, they begin to regain their self-assurance, but never to the same level as when they were uneducated. This pattern emerges because, as your knowledge deepens, you become more aware of its limitations.

If you wish to learn more, click here for an in-depth discussion on this topic.

“Dunning-kruger” by Jens Egholm Pedersen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Dunning-Kruger effect has been used to explain why non-medical professionals feel they are capable of challenging physicians’ recommendations to vaccinate their children. It also explains why lay-people with no training in climate science feel they can speak confidently about what the science says about human-caused climate change.

Wisdom requires humbleness. Our knowledge, after all, is always limited and flawed. Thus, those moments when we feel we are wise, when we are confident of our rightness, are when we are likely in the greatest danger of playing the fool.

Regardless of our uncertainty, we must still act. Acting while acknowledging our limitations requires us to proceed with a willingness to learn and adapt. We need to develop our ability to improvise when we reach a gap in our knowledge. Your ability to improvise improves as you broaden your education outside your specific field.[10] This does not mean you need to become a professional student and collect degrees throughout your life but rather to be curious about other disciplines. Create opportunities to learn from others. Doing this will broaden your perspective, which will allow you greater capacity to view problems from multiple angles and come up with clever solutions.

Finally, an attribute of wisdom is the recognition that the challenges we face are dynamic. Once people act, the problem will change. The best solution, therefore, may change over time. Retain your willingness to adapt as the challenge you face evolves.[11]

Key Takeaways

- A critical insight the wise possess is an understanding of the importance of values

- Those striving for wisdom recognize the power and limits of knowledge

- Wisdom requires humbleness

- Wisdom requires a willingness to act in the face of uncertainty, which is enhanced through developing an ability to improvise and broaden your base of knowledge outside your specialty

- Wisdom requires recognition that problems are dynamic, and thus our solutions must evolve in lock-step with our problems

Getting the Best Out of Your Experience

As you gain experience, you gain the ability to draw meaning out of your environment and integrate it into what you already know to develop appropriate actions.[12] Not all experience is created equal, however. As you might imagine, terribly upsetting and traumatic experiences may shut down a person’s growth. Working with a supportive mentor can help you avoid those situations and get the best out of your experience (more on mentors in a moment).[13]

Getting the Right Kind of Experience

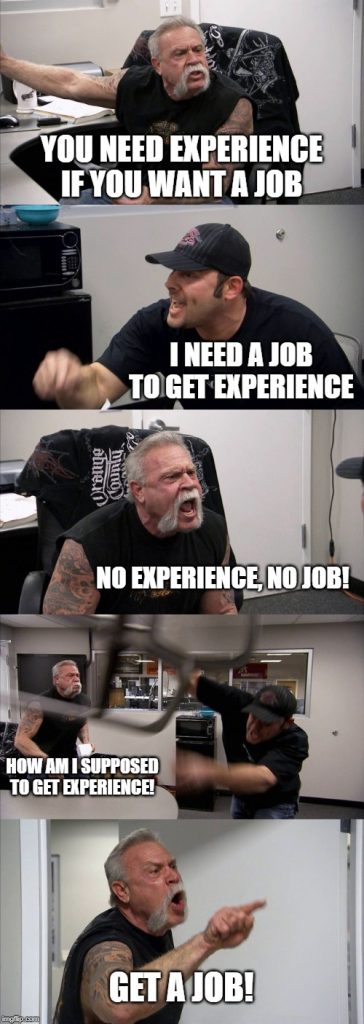

Students reading this section on the importance of experience may feel like throwing their hands up, lamenting the old paradox that, “You need experience to get a job, but you can’t get a job without experience.”

“Get a job” by Brad C. Anderson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

“Get a job” by Brad C. Anderson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

All cynicism aside, even students who have yet to start their careers have opportunities to gain experience. Take advantage of opportunities to work with industry partners, whether through class projects, internships, or co-op programs.[14][15][16] Select instructors who rely on experiential learning methods, which may include industry projects, computer simulations, team projects, cases, and so on.[17][18][19] These types of projects can mimic the experience of working in the ‘real world’ under the tutelage of your instructor, making them powerful learning opportunities.

If you have already begun your career, create opportunities to broaden your responsibilities. For example, you might volunteer for assignments that push you outside your comfort zone, especially if your employer is willing to mentor you. Speaking of mentoring, let’s turn to that topic next.

Key Takeaways

- Experience improves your ability to draw meaning out of your environment and integrate it into your thinking

- Not all experience is equal; some experiences are beneficial, but some may discourage personal growth

- As a student, take advantage of opportunities to work with industry partners

- Internships & co-op programs

- Select classes where teachers have you work with industry partners

- Select classes where teachers rely on experiential learning methods

- As an employee, create opportunities to broaden your responsibilities, especially under the mentorship of your boss, if they are willing

Mentoring

This section will look at the benefits of having a mentor and then explore how you can find someone willing to mentor you.

Benefits of a Mentor

The previous section identified that experience is an essential component of developing your wisdom, but experiences vary in their capacity to foster your growth. A good mentor will help you organize your experiences to pull out relevant learning.[20] They will challenge you to reflect on how you perceive the challenges you face, your methods of addressing those problems, the actions you have taken, and the effectiveness of those actions.[21][22]

Another benefit of mentoring is this. We learn from mistakes, but no one said those mistakes have to be our own. A good mentor will share their experience with you, helping you to avoid making the same mistakes they made.

“Zen proverb” by Brad C. Anderson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

All this may sound great, but how does one find a mentor? The next section explores this question.

Finding a Mentor

This section presents a North American business perspective. Consequently, some of the advice may be inapplicable to other industries and cultures. Do your due diligence to learn about the appropriate way to approach mentors in the field and culture in which you are operating.

Commonly, people feel nervous approaching others to ask for mentoring. Individuals in a position to mentor are often very busy and in positions of authority. It may feel like an imposition to ask them to give some of their valuable time to you.

Though people who have achieved the qualities that would make them a good mentor are often busy, you may be surprised by the number of people who are willing to help if you approach them with respect and a genuine desire to learn. Many people enjoy the opportunity to share what they have learned with others. The following paragraphs discuss the qualities of a good mentor, how to approach them, and then how to maintain the relationship.

A Good Mentor

A good mentor is someone you perceive as wise in an area you wish to develop. If you want to be a wise leader, seek out someone you consider a wise leader. If you hope to be a wise parent, seek out a wise parent, and so on. The person you reach out to for mentoring should be someone with whom you feel comfortable. Ideally, they will have had experience with the types of situations you face.

The criteria that make a mentor ideal for you may change as your vocation progresses. There will come times when you have learned all you can from one individual. Recognize that you may have many mentors throughout your life. Mentoring is not a “one and done” type of endeavor but rather a dynamic, life-long process.

Where to Find Mentors

Where can you find a mentor? There are many places, including but not limited to, the following.

- Work

- Your personal and professional network

- Mentorship programs

- Industry events

- Business associations

- Conferences

- Volunteering

- Social media

Approaching a Potential Mentor

Avoid asking, “Would you please be my mentor?” Be cool about it. Instead, reach out to them and ask if they have time for a short meeting (say, fifteen minutes), or if you could treat them to a quick coffee to discuss some questions you had about your career (or whatever topic on which you want mentoring). They may say no–people are busy, after all. If this is the case, thank them and move on with your search. If they agree, prepare for the meeting.

Preparing For Your Meeting

You will build a much stronger relationship with a mentor if you respect their time. Be organized. Consider ahead what your questions are. Your time with them may be brief, so have an idea of what insight you want to gain from that time and make a plan to get that insight.

What types of questions might you ask? Well, ask about whatever you would like insight on that is relevant to their experience. For example:

- Career planning: What expertise and training do you need for the career you want?

- Career insights: What does it take to be successful in this career?

- Advice: Share with them the challenges you are experiencing, how you are tackling them, and then ask whether they have any helpful ideas.

- And so on.

When meeting with them, present yourself in a manner that is respectful and appropriate for the circumstances. Wearing formal business attire may be necessary if you are meeting with a high-powered banking executive but out of place if your appointment is with an artist.

During The Meeting And Beyond

Be respectful of their time. If you asked for fifteen minutes, then let them know when you reach the fifteen-minute mark. If they are willing to speak longer, great. Otherwise, thank them and be on your way.

Be friendly and interested in them. Ask your questions. Have a discussion. Consider how you will remember any tidbits of good advice you receive. Will you take notes during the meeting? Write things down afterward?

If you feel you received value from the meeting and had a good rapport with the person, ask if you may contact them in the future to discuss further issues. If you got along well, you might feel comfortable calling them up to ask for advice whenever you hit a rough patch in your activities. Or, perhaps you might limit your interactions to two or so meetings a year.

Whatever the frequency, make a plan to meet with your mentor regularly and follow through on that plan.

Pay it Forward

Mentoring is a powerful tool to develop the capacity of individuals to act wisely. Through mentoring, we can learn from the experience of others. Regardless of your stage of life, you have experiences from which someone else can learn. Societies grow strong when we leverage our expertise to strengthen each other.

The world needs to hear your stories, so please share them. Look for opportunities to mentor others. Not only will mentoring others help them, but it also helps you. Mentoring requires that you reflect deeply on your experiences so you can pull out relevant lessons. As the next section discusses, this type of reflection is a potent, personal tool to develop your inner wisdom.

Key Takeaways

- A good mentor will help you organize your experiences to pull out relevant learning

- A good mentor will share their experience with you, helping you to avoid making the same mistakes they made

- What makes a mentor “good?”

- You look up to them as a wise leader

- You feel comfortable talking to them

- They have experience in the situations you face

- When approaching a potential mentor

- Ask permission to meet with them

- Be respectful of their time

- Come to the meeting prepared

- Maintain your relationship with them

- Pay it forward; sharing your experiences by mentoring others helps them as well as gives you a deeper understanding of your own experience

Reflection Journaling

Earlier, this textbook claimed that experience was one of the most effective ways to develop wisdom. This sentiment is, alas, somewhat inaccurate. We do not learn through experience but by reflecting on our experience.

“Reflection” by Brad C. Anderson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

Reflection journals are a tool to facilitate the contemplation of our actions and their outcomes. The methods the following sections describe are based on several sources, but you may adapt them to your needs.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

When making journal entries, you may use text, audio, video, or whatever format you prefer. What is important is your ability to record your reflections in a way that you can come back and easily review them at a later date.

What to Include in Your Journal

Regularly (several times a week)

Describe the event: Describe events that occur during your day. Focus on the actions you take and the decisions you make. Include meaningful discussions, disagreements, and so on. Record successes and things that trouble you.

State the rationale for your actions: What were you thinking? Why did you act the way you did? Be sure to address the following elements as you discuss your rationale.

- Values: What values does your action express?

- Emotions: This is a big one. We like to think we are rational performance machines. In reality, we often make decisions based on our feelings. Reflect on what you were feeling during the event you described. It is critical to reflect on how those emotions influenced your actions. The goal is not to eliminate your feelings but to gain insight into how your emotions affect your performance.

- Rationale: What was the intellectual underpinning of your actions? What was the type of rationality on which you relied (e.g., technocratic, body, bureaucratic, etc.)?

- Assumptions: What assumptions were implicit in the choices you made?

What was influencing other individuals in the encounter: If your event involved other people, what do you believe was driving their actions? What values, emotions, and rationale do you think influenced them?

Short term outcome: What was the immediate result of your actions? Are you happy with the outcome? If yes, what was the key to achieving that outcome? If no, what prevented you from getting the result you wanted?

Short term lessons learned: Did you get any insights from this experience? Highlight them so you can easily refer back to them later.

Action items: Based on the above reflection, are there any actions you need to take?

Periodically (every three to four months)

Review your journal: Scan through your journal every few months.

Long-term outcomes: Assessing long term effects of our actions is critical, yet easy for us to ignore. Our efforts have long-lasting effects. We need to teach ourselves to see these consequences. Now that time has passed since your initial decision, are there any long-term consequences to note? Are you happy with those long-term effects? Why or why not?

Trends: Do you notice any trends in your behavior? Does the same situation arise frequently? Do you make the same mistakes time and again? Is there a system you can put in place to address these recurring issues?

Long-term lessons learned: Based on the above reflection, are there additional lessons you have learned? Highlight critical learnings so you can remind yourself of them often.

Action items: Identify any actions you need to take based on these long-term lessons you learned.

Key Takeaways

- We do not learn from experience but from reflecting on our experience

- Reflection journals are a tool to facilitate the contemplation of our actions and their outcomes

- Reflect regularly through the week on your actions and the values, assumptions, and rationale behind your decisions

- Periodically through the year, revisit your reflections to pull out recurring themes in your performance and decision-making

Developing Social and Emotional Intelligence

Organizational wisdom is a group activity. Working well with people requires social and emotional intelligence. You can develop this type of intelligence through cooperative learning, taking interdisciplinary courses, and (the most enjoyable bit of advice ever) indulging your interest in whatever art forms you enjoy.

Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning means working in groups. Life gives us no shortage of opportunities to engage in group work. These opportunities include playing on sports teams, joining clubs, being a part of a workgroup, team projects in class, and so forth. The best opportunities to develop your social and emotional intelligence come from being in a group that is working towards a particular goal under pressure. This pressure forces people to interact in productive ways. Combining these activities with your reflection journal can create potent opportunities to deepen your insight into social and emotional considerations of group efforts.[29][30]

Interdisciplinary Courses

Chapter 5‘s discussion on rationality alluded to the idea that different disciplines indoctrinate their practitioners into various forms of rationality (e.g., business schools teach economic rationality, science schools technocratic, and so on). When all you know is one form of rationality, people acting on different types of rationality may seem strange and, perhaps, a bit clueless about the things you think are essential. Fear not, for they likely feel the same way about you!

Breaking this barrier requires you to work with people from different educational backgrounds. If you are in school, look for interdisciplinary classes where not only are your fellow students from different disciplines but so are the teachers.[31] Outside of school, look for opportunities to volunteer or work with community groups of diverse backgrounds. Again, combining this experience with your reflection journal will help you see the blind spots of your preferred form of rationality and see the strengths of others.

Indulge your Appreciation for the Arts

Arts include any form of human expression, such as cinema, literature, music, dance, painting, baking, crafts–any artistic endeavor. An appreciation of the arts can develop social and emotional intelligence through increasing imagination, empathy, and a sense of connectedness.[32][33]

Most people are drawn to some art form. Follow your interests and dive into them. If you participate in art as a hobby, say, playing the guitar or drawing, carve time into your week to practice your craft. If you are not called to create, you still most likely enjoy experiencing artistic endeavors, whether it be reading, watching live music, attending dance performances, or whatever. Indulge that interest.

Yes, that’s right. A school textbook is telling you to turn off the computer and do something fun.

Key Takeaways

- Organizational wisdom is a group activity, and working well with others requires social and emotional intelligence

- You can develop your social and emotional intelligence through:

- Cooperative learning: Working with groups. Combine this with reflection journaling for enhanced learning

- Interdisciplinary courses: These are courses where teachers from multiple disciplines teach students from various disciplines

- Indulging in your appreciation of the arts: All forms of artistic expression increase imagination, empathy, and a sense of connectedness

This textbook has thus far explored the nature of wisdom and how you can enhance this capacity in yourself. At the end of the day, however, wisdom is action-oriented. Therein lies one of the biggest hurdles to our ability to act wisely. Acting requires not only the willingness to take the time and effort to do something but bravery as well. Taking action is hard and risky. The following chapter discusses this one last hurdle.

In This Chapter, You Learned

The challenges of developing wisdom

- Wisdom is context-dependent

- Wisdom cannot be objectively measured

- We gain wisdom with experience

A wisdom-oriented mindset

- A critical insight the wise possess is an understanding of the importance of values

- Those striving for wisdom recognize the power and limits of knowledge

- Wisdom requires humbleness

- Wisdom requires a willingness to act in the face of uncertainty, which is enhanced through developing an ability to improvise and broaden your base of knowledge outside your specialty

- Wisdom requires recognition that problems are dynamic, and thus our solutions must evolve in lock-step with our problems

How to get the best out of your experience

- Experience improves your ability to draw meaning out of your environment and integrate it into your thinking

- Not all experience is equal; some experiences are beneficial, but some may discourage personal growth

- As a student, take advantage of opportunities to work with industry partners

- Internships & co-op programs

- Select classes where teachers have you work with industry partners

- Select classes where teachers rely on experiential learning methods

- As an employee, create opportunities to broaden your responsibilities, especially under the mentorship of your boss, if they are willing

The importance of good mentors

- A good mentor will help you organize your experiences to pull out relevant learning

- A good mentor will share their experience with you, helping you to avoid making the same mistakes they made

- What makes a mentor “good?”

- You look up to them as a wise leader

- You feel comfortable talking to them

- They have experience in the situations you face

- When approaching a potential mentor

- Ask permission to meet with them

- Be respectful of their time

- Come to the meeting prepared

- Maintain your relationship with them

- Pay it forward; sharing your experiences by mentoring others helps them as well as gives you a deeper understanding of your own experience

How to maintain an effective reflection journal

- We do not learn from experience but from reflecting on our experience

- Reflection journals are a tool to facilitate the contemplation of our actions and their outcomes

- Reflect regularly through the week on your actions and the values, assumptions, and rationale behind your decisions

- Periodically through the year, revisit your reflections to pull out recurring themes in your performance and decision-making

Ways to develop social and emotional intelligence

- Organizational wisdom is a group activity, and working well with others requires social and emotional intelligence

- You can develop your social and emotional intelligence through:

- Cooperative learning: Working with groups. Combine this with reflection journaling for enhanced learning

- Interdisciplinary courses: These are courses where teachers from multiple disciplines teach students from multiple disciplines

- Indulging in your appreciation of the arts: All forms of artistic expression increase imagination, empathy, and a sense of connectedness

- McNamee, S. (1998). Reinscribing Organizational Wisdom and Courage: The Relationally Engaged Organization. In S. Srivastva & D. L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Organizational Wisdom and Executive Courage1 (pp. 101–117). San Francisco: The New Lexington Press. ↵

- Pitsis, T. S., & Clegg, S. R. (2007). Interpersonal Metaphysics--"We Live in a Political World": The Paradox of Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 399–422). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Sampson, E. E. (1998). The Political Organization of Wisdom and Courage. In S. Srivastva & D. L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Organizational Wisdom and Executive Courage (pp. 118–133). San Francisco: The New Lexington Press. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction--Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R. E., & McKee, A. (2013). Primal Leadership: Unleashing the Power of Emotional Intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction--Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction--Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction--Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction--Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Jordan, J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2007). Individual Logic--Wisdom in Organizations: A Balance Theory Analysis. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 3–19). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Bierly III, P. E., Kessler, E. H., & Christensen, E. W. (2000). Organizational Learning, Knowledge and Wisdom. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13(6), 595–618. ↵

- Dewey, J. (1998). Experience and Education (60th Anniv). Indianapolis: Kappa Delta Pi. ↵

- Fowers, B. J. (2003). Reason and Human Finitude in Praise of Practical Wisdom. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(4), 415–426. ↵

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books. ↵

- Talbot, M. (2004). Good Wine May Need to Mature: A Critique of Accelerated Higher Specialist Training. Evidence from Cognitive Neuroscience. Medical Education, 38(4), 399–408. ↵

- Bartunek, J. M., & Trullen, J. (2007). Individual Ethics--The Virtue of Prudence. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 91–108). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Conger, J., & Hooijberg, R. (2007). Organizational Ethics--Acting Wisely While Facing Ethical Dilemmas in Leadership. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 133–150). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Statler, M., & Roos, J. (2006). Reframing Strategic Preparedness: An Essay on Practical Wisdom. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy, 2(2), 99–117. ↵

- Dewey, J. (1998). Experience and Education (60th Anniv). Indianapolis: Kappa Delta Pi. ↵

- Baltes, P. B., & Kunzmann, U. (2004). The Two Faces of Wisdom: Wisdom as a General Theory of Knowledge and Judgment about Excellence in Mind and Virtue vs. Wisdom as Everyday Realization in People and Products. Human Development, 47(5), 290–299. ↵

- Freeman, R. E., Dunham, L., & McVea, J. (2007). Strategic Ethics--Strategy, Wisdom, and Stakeholder Theory: A Pragmatic and Entrepreneurial View of Stakeholder Strategy. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 151–177). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Adler, N. J. (2007). Organizational Metaphysics–Global Wisdom and the Audacity of Hope. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 423–458). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Coulson, D., & Harvey, M. (2013). Scaffolding student reflection for experience-based learning: A framework. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(4), 401–413. ↵

- Gardner, H. (2011). Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership. New York: Basic Books. ↵

- Harvey, M., Coulson, D., & McMaugh, A. (2016). Towards a theory of the Ecology of Reflection: Reflective practice for experiential learning in higher education. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 13(2). ↵

- Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction–Understanding, Applying, and Developing Organizational and Managerial Wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books. ↵

- Cooper, J. L., Robinson, P., & McKinney, M. (1994). Cooperative Learning in the Classroom. In D. F. Halpern (Ed.), Changing College Classrooms: New Teaching and Learning Strategies for an Increasingly Complex World (pp. 74–92). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1991). Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Co. ↵

- Fukami, C. V., Clouse, M. L., Howard, C. T., McGowan, R. P., Mullins, J. W., Silver, W. S., … Wittmer, D. P. (1996). The Road Less Traveled: The Joys and Sorrows of Team Teaching. Journal of Management Education, 20(4), 409–410. ↵

- Freeman, R. E., Dunham, L., & McVea, J. (2007). Strategic Ethics--Strategy, Wisdom, and Stakeholder Theory: A Pragmatic and Entrepreneurial View of Stakeholder Strategy. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational and Managerial Wisdom (pp. 151–177). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. ↵

- What Businesses Can Learn from the Arts. (2019). Retrieved December 9, 2019, from https://www.economist.com/business/2019/12/08/what-businesses-can-learn-from-the-arts ↵

A phenomena that is dependent on a specific social situation. As the social situation (i.e. the context) changes, so, too, does the phenomena.

Motivated by their personal values, champions drive action in their organization. They possess specific characteristics.

- They are passionate about the cause they champion. They exhibit enthusiasm, optimism, and resilience.

- They possess the skills needed to produce useful power relations.

- They possess sufficient bureaucratic rationality to know how to implement activities in their organization's structure.

- They are adaptable.

- They are realistic about what they can accomplish within their organization.

The awareness of your emotions and those of others combined with the ability to manage these emotions constructively.