6 Power

Brad C. Anderson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn the following:

- The dimensions of power

- The faces and sites of power in organizations

- How people and groups exercise power

- How this textbook views power

If your teacher told you to pick up their dry cleaning, would you? Is it okay for a teacher to demand such a thing of you?

Most people agree that it is inappropriate for a teacher to ask you to perform personal favors. Yet, your teacher will require you to prepare reports and write exams. Conducting research and studying requires many hours per week of work. When you compare the effort of picking up dry cleaning to studying for a final exam, the work needed to pass a test is greater than picking up someone’s clothes. Nonetheless, a student who willingly loses sleep to complete a report for the teacher would likely reject that teacher’s request to pick up their laundry.

How is it a teacher can ask you to give hours for a term project yet remain unable to have you take twenty minutes to swing by the laundromat?

You might argue that the teacher gives you marks for school work but not personal favors. The teacher’s authority, then, is bound by what they can legitimately assign grades for. What allows the teacher to give you marks, however? Is there something preventing the teacher from having a graded assignment on picking up laundry? Is there a reason why that teacher marks your work rather than another teacher? Why does a teacher, rather than a classmate, grade your assignments? Why do we have marks at all?

The social structure of power answers these types of questions. Power is a creative force. Through the creation of webs of power, humans organize themselves into collective entities ranging in size from small teams to entire civilizations. This ability to organize is humanity’s killer app.

People commonly view power negatively. They see power as something a stronger aggressor does to a weaker victim. They see power as the ability to get other people to do something, often against their will. Thus, we fear the power that others might have over us.[1]

It is undeniable that some people have more power than others. It is also undisputed that these power asymmetries have led to oppression. Despite these truths, this textbook takes a decidedly optimistic view of power. Though power can lead to abuse, it is equally valid that it is through power we right injustice. Power is a creative force, and we each have the agency to choose what it is we create.

Wisdom is action-oriented. Acting requires you to exercise your power within your social setting. For your actions to have the desired effect, you must understand how the web of power governing your social setting works.[2]

To that end, this chapter summarizes several frameworks of power. It starts by exploring the dimensions of power that scholars have identified. Following this, it presents a discussion on the faces and sites of power in organizations, which considers how people experience power and where power operates in social systems. Then, this chapter will discuss how people exercise power in organizations, focusing on the connection between power and rationality and the different relations into which groups with power enter. This chapter then concludes with a perspective on power that readers will find helpful when seeking to develop wisdom in the organizations in which they operate.

This chapter serves to present a basic overview of power. Later sections of this textbook will then dive deeper into how power operates in organizations to give you a richer understanding of this topic.

As you read the following, please remember that for millennia, countless theorists and philosophers across the world have contemplated power. The literature and teachings describing power are, consequently, vast and filled with conflicting views. The creators of the frameworks this textbook presents were Western European/North American scholars. Thus, they premise their work on a body of Western research and philosophy. Other cultures will have different traditions of power.

By focusing on these frameworks, this textbook is not implying they are the only ways to understand power. Instead, this textbook presents these frameworks because the author believes they provide practical insights to individuals seeking to take action within their social setting. You may find other conceptualizations of power more relevant to your circumstances.

Dimensions of Power

Steven Lukes developed a framework that identified three dimensions of power.[3] The first two dimensions consider power as it pertains to conflicting interests between parties. The third dimension explores how those with power can avoid clashes of interests by shaping the wants and desires of others. Later, other scholars identified a fourth dimension that saw power as a web of relations that provides the scaffolding of societies.

The One-Dimensional View of Power

Under the first dimension, power is the ability to get someone to do what you want. Here, power is active in direct, observable conflicts. Our focus is on the behaviors people deploy in the process of decision-making when the interests of different parties are in opposition.

The Two-Dimensional View of Power

Whereas power’s first dimension considers the ability of one party to secure the compliance of other another when interests conflict, the second dimension considers how those with power suppress conflict. That is, a group has power if it can limit the scope of what is debated, thereby confining decision-making to issues they deem safe. Parties may achieve this through various means.

- Coercion: You secure the compliance of others through threats of deprivation. For example, an employer may say, “Do this, or I will fire you.”

- Influence: You secure the compliance of others without resorting to threats. You, instead, convince others to comply through various means (e.g., making a persuasive argument).

- Authority: Others comply with you because they recognize your authority (e.g., a young child may obey their parents because the parents are in charge).

- Force: You secure the compliance of others by stripping from them the choice of non-compliance (e.g., the police may close off the road, forcing you to find another route home).

- Manipulation: You secure the compliance of others without their awareness (e.g., a company may withhold data about the negative side-effects of its products so that you buy them).

With both the first and second dimensions of power, there exist conflicts of interests between parties. The first dimension resolves those differences through open conflict, the second by suppressing one side’s ability or willingness to engage in a public battle. The third dimension considers the ability of those with power to avoid the need for conflict altogether.

The Three-Dimensional View of Power

The third dimension of power considers the ability to avoid conflict. Those with power can shape people’s perceptions of their situation and influence how they think and understand the world. Through such means, those with power can shape the preferences of others to the point they comply because they are incapable of imagining an alternative. They see compliance as natural.

For example, a business may promote the idea that a sign of good character is a willingness to work hard. Going above and beyond the call of duty is a virtue. The business rewards people who possess that virtue with promotions and career advancement. Over time, a worker immersed in this environment may come to believe that hard work is a virtue. Then, when the company asks that worker to work unpaid overtime on the weekend, the person may choose to do so willingly. They sacrifice their time for the company’s good not out of coercion, but because they believe doing so is virtuous. The company has shaped the worker’s beliefs and preferences to the point the worker adopts the interests that the company has.

A Contentious Fourth Dimension of Power

Another scholar, Michel Foucault, wrote extensively on power. Some people view his perspective as a fourth dimension. Dr. Lukes, who conceptualized the first three dimensions, disagrees with this. That is why this section is titled a “contentious” fourth dimension. Foucault’s work is influential, however, and people categorize it as a fourth power dimension. This textbook, therefore, introduces it here briefly.

The first three dimensions view power as repressive. They explore how the interests of one party may prevail over another either through conflict, suppressing conflict, or shaping preferences. Foucault, conversely, viewed power as productive. Through power, civilizations create things. One of the more critical items they create is individuals, or what Foucault called “subjects.” Society creates subjects through indoctrinating people into roles and beliefs, by transferring cultural knowledge to them, and then monitoring people’s behavior and enforcing norms. Through these processes, we create doctors, teachers, mothers, fathers, and every other subject that plays a part in society.

Foucault argued power was active in “micro-practices,” or the daily activities of life. When you exchange money for coffee, you reinforce the power structures through which our society creates an economy. When you study to do well on an exam, you reinforce the power structures through which our society transfers knowledge. Society is a rich web of power relations; our daily actions serve to create and re-create these webs.[4][5]

Key Takeaways

- Scholars have classified power into four dimensions

- One-dimensional power: The ability to get people to do something that you want through open conflict

- Two-dimensional power: The ability to get what you want through suppressing conflict and limiting the scope of debate

- Three-dimensional power: The ability to get what you want by influencing the preferences of others

- Four-dimensional power: The dense web of power networks through which societies organize themselves

The Faces And Sites of Power

Peter Fleming and André Spicer developed a framework that sought to organize the vast collection of scholarly thought on power. Their model has two categories: faces of power and sites of power.[6]

Faces of Power

The faces of power describe the forms through which people experience power. As you read about these faces, you will see similarities between it and the dimensions of power described earlier. See if you can connect the faces of power described below to power’s dimensions discussed above.

Fleming & Spicer identified two faces of power: episodic and systematic.

You can think of episodic power as the direct exercise of power. It includes coercion and manipulation.

- Coercion is the use of power to compel another party’s compliance when they otherwise would not comply. What are the sources of power that give one party the ability to coerce another? There are several, including:

- Bureaucratic authority

- A psychological propensity to use force or threats

- A capability to reduce uncertainty

- Possession of valuable resources

- Manipulation is the use of power to control the topics people discuss and to frame the issues discussed within desired boundaries. The power to manipulate comes from several sources, including:

- The ability to manipulate rules of conduct

- Being able to define the outcomes that people expect

- Mobilizing bias for or against certain issues within an organization

- Influencing the process through which people make decisions

Whereas episodic power is the direct exercise of power to obtain the compliance of others, systematic power considers the web of power that creates organizing structures within our society. It includes domination and subjectification.

- Domination is the use of power to shape people’s preferences and influence their interests. Domination occurs through several means, including:

- Indoctrination into an organization’s culture

- Adopting the unquestioned assumptions that guide behavior in a field of endeavor

- Adhering to an institution’s norms of operation

- Adopting those behaviors and beliefs that an organization perceives as legitimate

An Example of Domination

It can be tricky to wrap your head around the idea of domination. Let’s look at an example to clarify. As listed above, the sources of domination included things like culture, unquestioned assumptions, norms, and behaviors/beliefs the organization sees as legitimate. How might this operate in, let’s say, a hospital?

The hospital’s organizational culture might value saving lives. It may pursue this value because this is what society expects hospitals to do–that is, saving lives is a legitimate pursuit. Healthcare workers in that hospital adopt those values. Then, when a patient comes to see a doctor, the doctor assumes the patient wants to live longer. They then choose to perform actions to save that patient’s life.

Through these processes of domination, healthcare workers see saving lives as the natural course of action. Doing anything else is unimaginable.

What happens, then, when a patient with an incurable illness arrives suffering terribly from pain and disability? Physicians cannot save the patient’s life–the disease is fatal. Prolonging life merely prolongs the patient’s suffering. What is the role of healthcare workers, then?

- Subjectification is the process through which individuals obtain their sense of identity within a social system. Through conforming to these identities, people perform specific actions, assume different levels of authority, and adopt prescribed beliefs and values. Subjectification occurs through several means, such as:

- Working in groups

- Monitoring of individual behavior within a group

- Development of strategies that identify specific roles that individuals fill

- The creation of words and concepts that defines identities and functions (e.g., manager, cashier, teacher, student). Each of these words means something, and when you apply that title to yourself, you take on that meaning as part of your identity.

As mentioned earlier, there is an overlap between these faces of power and the dimensions of power the previous section described. The following table summarizes these areas of overlap. Coercion intersects with the concept of one- and two-dimensional power. Power’s second dimension aligns with manipulation. Domination, conversely, overlaps with the third- and fourth-dimensions of power, whereas subjectification overlaps with the fourth dimension.

| One-dimensional power | Two-dimensional power | Three-dimensional power | Four-dimensional power | |

| Coercion | + | + | ||

| Manipulation | + | |||

| Domination | + | + | ||

| Subjectification | + |

Sites of Power

In addition to describing the faces of power, Fleming and Spicer identified four sites of power surrounding the organization. These include power in, through, over, and against the organization.

- Power in organizations describes the efforts of individuals within an institution’s boundaries to affect its structures governing the organization. Examples include resisting change initiatives, conflicts between staff and their managers, dealing with whistleblowers, and so on.

- Power through organizations describes the efforts to use the organization to achieve an objective outside the organization. Examples include government or non-governmental agencies partnering with other institutions to pursue some political end.

- Power over organizations describes the efforts of influential individuals or groups to exert influence over an organization. Examples include shareholder activism, intervention by government regulators, and lobbying by third-parties to change a business’s activities.

- Power against the organization describes the efforts of outside individuals or groups to create a change in the structures governing the organization. Examples include tapping into social movements to create change (e.g., women’s rights movement driving gender equity in salary structures and advancement opportunities within an organization)

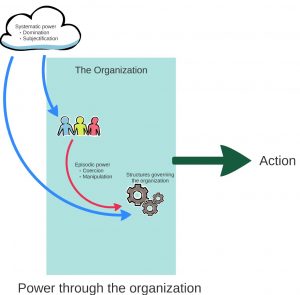

The following series of figures visually represent the relationship between the faces of power and the sites of power in organizations. The diagram below shows power in organizations. Individuals inside the organization use episodic forms of power as they contest each other for the ability to shape the structures governing the organization. Systematic power shapes the preferences and behaviors of individuals and the structures governing the organization.

The next figure shows power through organizations. Individuals inside the organization use episodic forms of power to drive the structures governing the organization, creating the actions of the organization. Systematic power shapes the preferences and behaviors of individuals and the structures governing the organization.

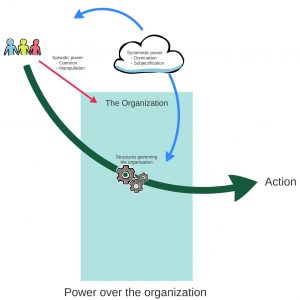

The next figure shows power over organizations. Individuals outside the organization use episodic forms of power to drive the structures governing the organization, influencing the actions of the organization. Systematic power shapes the preferences and behaviors of individuals and the structures governing the organization.

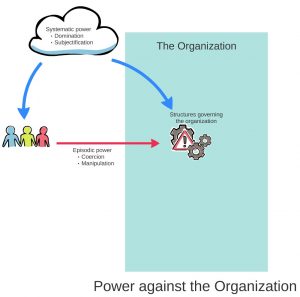

The next figure shows power against the organization. Individuals outside the organization use episodic forms of power to contest the organization’s governing structures. Systematic power shapes the preferences and behaviors of individuals and the structures governing the organization.

Key Takeaways

- Faces of power describe the forms through which people experience power. These faces include episodic and systematic power

- Episodic power is the direct exercise of power, including coercion and manipulation

- Systematic power is the web of power that creates organizing structures within social systems, including domination and subjectification

- Sites of power define where power operates within organizations. It includes:

- Power in organizations

- Power through organizations

- Power over organizations

- Power against organizations

How Do People And Groups Exercise Power?

The previous section defined episodic power as the direct exercise of power, which includes coercion and manipulation. Bent Flyvbjerg identified several examples of how individuals and groups exercise power.[7] The tactics he identified fall into two categories: (i) power and rationality and (ii) power relations

Power and Rationality

As later chapters will explore, many scholars see a tight connection between power and rationality. As the previous chapter discussed, we use rationality to justify our actions and determine our course of action. Thus, if I can influence what you perceive as rational, then I can influence your actions. That gives me power.

Exercises

If I seek to influence your actions by shaping what you perceive as rational:

- Using Lukes’s three-dimensions of power, which dimension am I exercising?

- Using Fleming & Spicer’s faces of power, which face am I utilizing?

The relation between rationality and power takes several forms.

- Defining rationality: Those with power seek to shape what others perceive as rational. This process can be as benign as two friends debating what movie they will watch tonight. Each may use their forms of reason and persuasion to convince the other. This process may also be much less benign. An institution might, for example, seek to sway public opinion by hiding the results of studies showing its activities cause harm.

- Ignoring rationality: This is the ability of parties to perform irrational acts without consequence. For example, an analysis might conclude the optimal spot to locate a business is in Neighborhood A. The owner of the company lives in Neighborhood B and wants to avoid commuting to work. They subsequently choose to ignore the study and locate the business in Neighborhood B.

- Using rationalization as rationality: How do rationalization and rationality differ? Rationality is the process of using reason to understand the world and select actions. Rationalization is the process of finding excuses to justify the action you want to take (or already took). Using rationality means you use reason to guide your actions. Rationalization means you create a veneer of rationality to defend your actions. Power is the ability to use rationalization and have others accept it as rationality.

Power relations

The opening of this chapter stated that societies create webs of power that organize human activity. The phrase, “webs of power” implies that power is a matrix in which we are embedded. The social setting will assign more power to some individuals, less to others, depending on the role they play. That said, everyone has some power.

Moreover, power is dynamic. That means it shifts and changes. Think of power as a fluid rather than a solid. For example, a CEO may rule her company with an iron fist, yet when she needs surgery to remove cancer, her doctor reigns supreme. In one setting, the CEO is queen; in another, she is a supplicant. Power ebbs and flows.

Remember those two points: everyone has some power, and power is dynamic.

As individuals and groups exercise their power to act in a social setting, they encounter other individuals and groups in possession of their power to act. The relative power each party possesses may be equal, but frequently, one group will have more power relative to another. Consequently, the interactions between groups can become quite complex as each party pursues its aims. The relations between these different strands of power take several forms.

- Maintaining stability: One party takes purposeful action to avoid conflict with another party. For example, a human resources administrator may voluntarily choose to seek a department’s approval before implementing a new safety policy. Even though they may not need the department’s approval, they may seek it to avoid the possibility the department will resist the new policy later.

- Conflict: One party openly defies and seeks to defeat another party. For example, a union may go on strike to protest the unsafe working conditions a company maintains.

- Production of power relations: Two or more parties take action to form a working relationship with each other. For example, an individual may sign an employment contract with a company, or two departments in a company may arrange how they will work together.

- Reproduction of power relations: Two or more parties currently in a working arrangement with each other take actions to reinforce that arrangement. These actions could be as simple as choosing to abide by the conditions of the arrangement. For example, an employment contract may stipulate annual performance evaluations, and so both employee and employer partake in these annual evaluations. These actions could also include modifying existing arrangements as new situations arise. For example, two cooperating departments might revise their communications processes when the company introduces new IT infrastructure.

- Historical power relations: Social settings are open systems. Open systems affect and are affected by the outside world. There is also a time-aspect to open systems. Past events can affect the present. Historical power relations refer to actions parties take as a consequence of long-standing relations with other parties.

Key Takeaways

- People and groups exercise power through several means.

- Power and rationality, including defining rationality, ignoring rationality, and using rationalization as rationality

- Power relations, including maintaining stability, conflict, production of power relations, reproduction of power relations, historical power relations

So, How Will You View Power?

The above sections present several ways that power manifests in social systems. This knowledge may help us to recognize when someone is trying to exert power over us. It may help us exercise our power more thoughtfully. Because of the impact power has, though, it takes on a moral quality. Consequently, we need to decide how we choose to perceive power. Is power dangerous, something we must strive to contain? Or, is it a force of creation, something we must nurture and shape? Maybe a little of both?

You will have to decide this for yourself. This textbook, however, is written with a specific view of power. Since this book is an exercise of power–it is attempting to define rationality–it is essential to state this textbook’s perspective explicitly. You can then judge whether you will adopt this perspective yourself.

This Textbook’s View of Power

It is common for people to view power negatively. We see power asymmetries leading to oppression, which in turn leads us to fear the power that others have over us. Consequently, people strive to protect themselves by either gaining power of their own or dismantling the power that others have.

Though asymmetries in power can lead to oppression, it is through the exercise of power we right these injustices. This textbook, thus, argues power is a creative force through which we build societies. To that end, it has adopted a conceptualization of power developed by Dr. Flyvbjerg, described below.

Dr. Flyvbjerg formulated a means to conceptualize power consistent with the development of phronesis. Some of these points may seem abstract right now. Later chapters will dive deeper into how power operates in organizations. In those chapters, you will see practical examples of how these following principles apply.

Dr. Flyvbjerg summarized his conceptualization of power as follows.[9][10]

- Power is a positive and creative force: It is through the exercise of power that civilizations create themselves.

- Power exists as a dense web of social relations: Power is the organizing force of civilization. Social systems consist of countless roles people fill. Societies define behaviors and authorities for each function that integrates with the many other duties people fill. Power, thus, is a web of actions and authorities that serves as the scaffolding for society.

- Power is dynamic: Societies are vibrant. So, too, is the web of power that constitutes those societies. People fill multiple roles throughout the day and their power changes with each function they fill (e.g. from VP at a bank to a patient in a doctor’s office). Moreover, people continuously negotiate and renegotiate the relations between different roles in society (e.g., a worker may discuss with their boss changes to their schedule). Consequently, the web of power governing a social system is ever-evolving.

- Power produces knowledge, and knowledge produces power: People create rationalities that justifies their actions and get them what they want (i.e., power produces knowledge). Likewise, the rationality a social system creates will lead people to conclude that certain parties must do certain things. This knowledge empowers those parties to do those things (i.e., knowledge produces power).

- How power is exercised is more important than identifying who has power: Creating action in an organization requires knowledge of how power works in that specific social setting. How are decisions approved? How are changes made? Through what mechanisms does the system control people’s actions? Part of this process will require you to learn who is responsible for making which decision, but knowing who has power is insufficient to drive action. You must understand how people in the social system exercise that power.

- Start your study of power with small questions: Recall from the earlier discussion of power’s fourth dimension that power was active in “micro-practices” or the daily activities of life. You will gain an understanding of how power is exercised by looking at these micro-practices (that is, by asking small questions). For example, how do you get your topic on a meeting agenda? What types of criticism might your plan face from individuals within the organization? How does a manager determine what tasks their employees will perform? How do you set up a meeting with crucial decision-makers? To understand how people in the social setting exercise power requires that you know these nuances of life in the organization.

Key Takeaways

- Though there are many ways people view power, this textbook adopts an approach used when seeking to develop phronesis. The principles of this conceptualization include:

- Power is a positive and creative force

- Power exists as a dense web of social relations

- Power is dynamic

- Power produces knowledge and knowledge produces power

- How power is exercised is more important than identifying who has power

- Start your study of power with small questions

Wisdom is Action-Oriented

To act, you must use your power.[11] Wisdom, therefore, requires power–but it requires us to use power wisely. How do we use power wisely? Remember, values guide wise action, so we use power wisely when we exercise it in pursuit of values we venerate. Knowledge is required, but insufficient for wisdom. We use power wisely when we use it to define rationality consistent with the values we pursue. We use power wisely when we recognize the limits of rationality. Knowing rationality’s limits leads us to listen to the knowledge other groups possess, which creates a more vibrant picture of our problems and to develop innovative solutions.

The previous two chapters plus this one have presented frameworks to understand the three underlying structures of wisdom: values, rationality, and power. In real life, these structures do not operate in isolation but interact in vibrant and dynamic ways. The chapters in the following section of this textbook explore these interactions to give you real insights into how to facilitate the development of wise organizations.

In This Chapter, You Learned

The dimensions of power

- Scholars have classified power into four dimensions

- One-dimensional power: The ability to get people to do something that you want

- Two-dimensional power: The ability to get what you want through suppressing conflict and limiting the scope of debate

- Three-dimensional power: The ability to get what you want by influencing the preferences of others

- Four-dimensional power: The dense web of power networks through which societies organize themselves.

The faces and sites of power in organizations

- Faces of power describe the forms through which people experience power. These faces include episodic and systematic power

- Episodic power is the direct exercise of power, including coercion and manipulation

- Systematic power is the web of power that creates organizing structures within social systems, including domination and subjectification

- Sites of power define where power operates within organizations. It includes:

- Power in organizations

- Power through organizations

- Power over organizations

- Power against organizations

How people and groups exercise power

- People and groups exercise power through several means.

- Power and rationality, including defining rationality, ignoring rationality, and using rationalization as rationality

- Power relations, including maintaining stability, conflict, production of power relations, reproduction of power relations, historical power relations

How this textbook views power

- Though there are many ways people see power, this textbook adopts an approach used when seeking to develop phronesis. The principles of this conceptualization include:

- Power is a positive and creative force

- Power exists as a dense web of social relations

- Power is dynamic

- Power produces knowledge and knowledge produces power

- How power is exercised is more important than identifying who has power

- Start your study of power with small questions

- Hardy, C., & Clegg, S. R. (1996). Chapter 3.7: Some Dare Call It Power. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of Organization Studies (pp. 622–641). London, UK: Sage Publications. ↵

- Hardy, C., & Clegg, S. R. (1996). Chapter 3.7: Some Dare Call It Power. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of Organization Studies (pp. 622–641). London, UK: Sage Publications. ↵

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A Radical View (2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ↵

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Toronto: Random House. ↵

- Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality - Volume 1: An Introduction. Toronto, Canada: Random House. ↵

- Fleming, P., & Spicer, A. (2014). Power in Management and Organization Science. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 237–298. ↵

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago, United States: The University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago, United States: The University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Clegg, S. R., & Pitsis, T. S. (2012). Phronesis, Projects and Power Research. In B. Flyvbjerg, T. Landman, & S. Schram (Eds.), Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis (pp. 66–91). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Hardy, C., & Clegg, S. R. (1996). Chapter 3.7: Some Dare Call It Power. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of Organization Studies (pp. 622–641). London, UK: Sage Publications. ↵

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

The ability to get what you want from others through direct, open conflict

Obtaining what you want through suppressing conflict and limiting the scope of what is debated to issues you deem safe.

The ability to get what you want by influencing the preferences of others.

The dense web of power networks through which societies organize themselves.

Episodic power is the direct exercise of power. It includes coercion and manipulation.

Coercion is an form of episodic power. It is the use of power to compel another party's compliance when they otherwise would not comply.

Manipulation is a form of episodic power. It is the use of power to control the topics people discuss and to frame the issues discussed within desired boundaries.

Systematic power considers the web of power that creates organizing structures within our society.

Domination is a form of systematic power. It is the use of power to shape people's preferences and influence their interests.

Subjectification is a form of systematic power. It is the process through which individuals obtain their sense of identity within a social system.

Power in organizations describes the efforts of individuals within an institution's boundaries to affect the structures governing the organization.

Power through organizations describes the efforts to use the organization to achieve an objective.

Power over organizations describes the efforts of powerful individuals or groups to exert influence over an organization.

Power against the organization describes the efforts of outside individuals or groups to create a change in the structures governing the organization.

A tactic of power where one party seeks to shape what others perceive as rational.

Ignoring rationality is the ability of parties to perform irrational acts without consequence.

This is the ability to use rationalization and have others accept those rationalizations as rationality. (Note: Rationality is the process of using reason to select actions. Rationalization is the process of finding excuses to justify your actions)

One party takes purposeful action to avoid conflict with another party.

One party openly defies and seeks to defeat another party.

Two or more parties take action to form a working relationship with each other.

Two or more parties currently in a working arrangement with each other take actions to reinforce that arrangement.

Historical power relations refer to actions parties take as a consequence of long-standing relations with other parties.

A system that has an effect on and is affected by the outside world.

Ancient Greek for practical wisdom; prudence; mindfulness