3 Critical Realism: A Framework to Understand Organizations

Brad C. Anderson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn the following.

- What critical realism is

- The layers of social reality envisioned by critical realism, including:

- The real domain

- The actual domain

- The empirical domain

- How critical realism helps us understand organizations

- The relation between critical realism and organizational wisdom

Back in the 1990s, the Australian New South Wales Police Service underwent significant reform in response to a report of corruption among the ranks of law enforcement officers. Despite many changes to leadership and operations, old patterns of behaviors persisted. For example, whereas previously the service based promotions on officer seniority, they implemented systems to instead base promotions on merit. Yet, a decade after the introduction of this new system, senior officers continued receiving promotions over younger ones regardless of merit. The new system failed to change the organization’s behavior.[1] Implementing change is hard. Indeed, roughly seventy percent of major change programs fail to achieve their goals. Why is it so difficult to change how organizations operate?

This chapter answers that question by presenting a framework called critical realism. Critical realism is a model of how organizations (and society in general) operate. Many frameworks explain how systems of social activity work. Two popular ones besides critical realism include positivism and post-structuralism. Because both positivism and post-structuralism are quite popular, this text introduces them briefly before diving into the details of critical realism.

Positivism maintains that immutable laws govern human activity. Through the application of the scientific method, we can understand these laws and develop theories of how social groups operate. These theories, in turn, will then allow us to design systems that control how groups behave.

Conversely, post-structuralism argues social reality is created through discourse (i.e., language) rather than immutable laws. For example, we have the word ‘teacher.’ The role of ‘teacher,’ however, has no meaning without a ‘student.’ Embedded in the words ‘teacher’ and ‘student’ is a social relationship with defined authorities and responsibilities.

By ignoring positivism, poststructuralism, and all the other frameworks that exist, this textbook is not claiming critical realism is right while everything else is wrong. Instead, it focuses on critical realism because this framework helps us understand the forces that control an organization. Since wisdom is action-oriented, critical realism helps us create organizational action.

Key Takeaways

- Critical realism is a model of how social systems work

- Critical realism is one of many models of social systems

- This text focuses on critical realism because it has utility in conceptualizing forces governing organizational action

So, What is Critical Realism?

Let’s first distinguish the difference between the natural world and the social world. The natural world includes all the things in the universe, including stars, planets, gravity, and atoms. The social world is the world of human activity, and it includes things like teachers, students, money, and national borders. A critical difference between the two is the social world requires human action to exist. If all of humanity vanished tomorrow, stars and planets would still exist, but teachers and money would not.

Since human activity created things like teachers and students, you would think it would be easy to change the social world. If humans created the roles of teachers and students, and you are a human, then it should be a simple process for you to change the roles of teachers and students. Yet, these roles are resistant to change. Humans created these roles, but once set in place, some force protects them from change. Sure, people could alter these roles, but doing so across society would be extremely hard.

Moreover, many of you have likely never thought about the socially constructed nature of things like teacher-student relations. You have probably never wondered why the teacher has the right to set assignments that you will lose sleep trying to finish. Yet, when the teacher asks you to write a report, you sacrifice evenings and weekends to write a report. You probably never wondered why raising your hand is the conventional way to get the teacher’s attention rather than, say, tapping your knuckles on the desk. Yet, when you raise your hand, the teacher calls on you, but if you rap your knuckles on the desk, they tell you to stop being disruptive. Even when we are unaware of the social structures that constitute human activity, these structures still have the power to enable or constrain the actions we can take. These structures have power over us even if we are ignorant of their presence or nature.

Furthermore, the nature of teacher-student relations existed long before you first walked into a classroom. They will likely persist long after you step in a class for the last time. Thus, even though these social structures exist only in the mind of humans, they possess a quasi-permanence separate from any one individual.

In total, once these social structures are created, they resist change. They have the power to enable or constrain your actions regardless of whether you are consciously aware of them, and they are semi-permanent.[2] Not bad for figments of our imagination.

Layers of Social Reality

To explain the observations described in the previous section, Roy Bhaskar developed the philosophy of critical realism. He described social reality as having three layers.[3]

- The real domain

- The actual domain

- The empirical domain

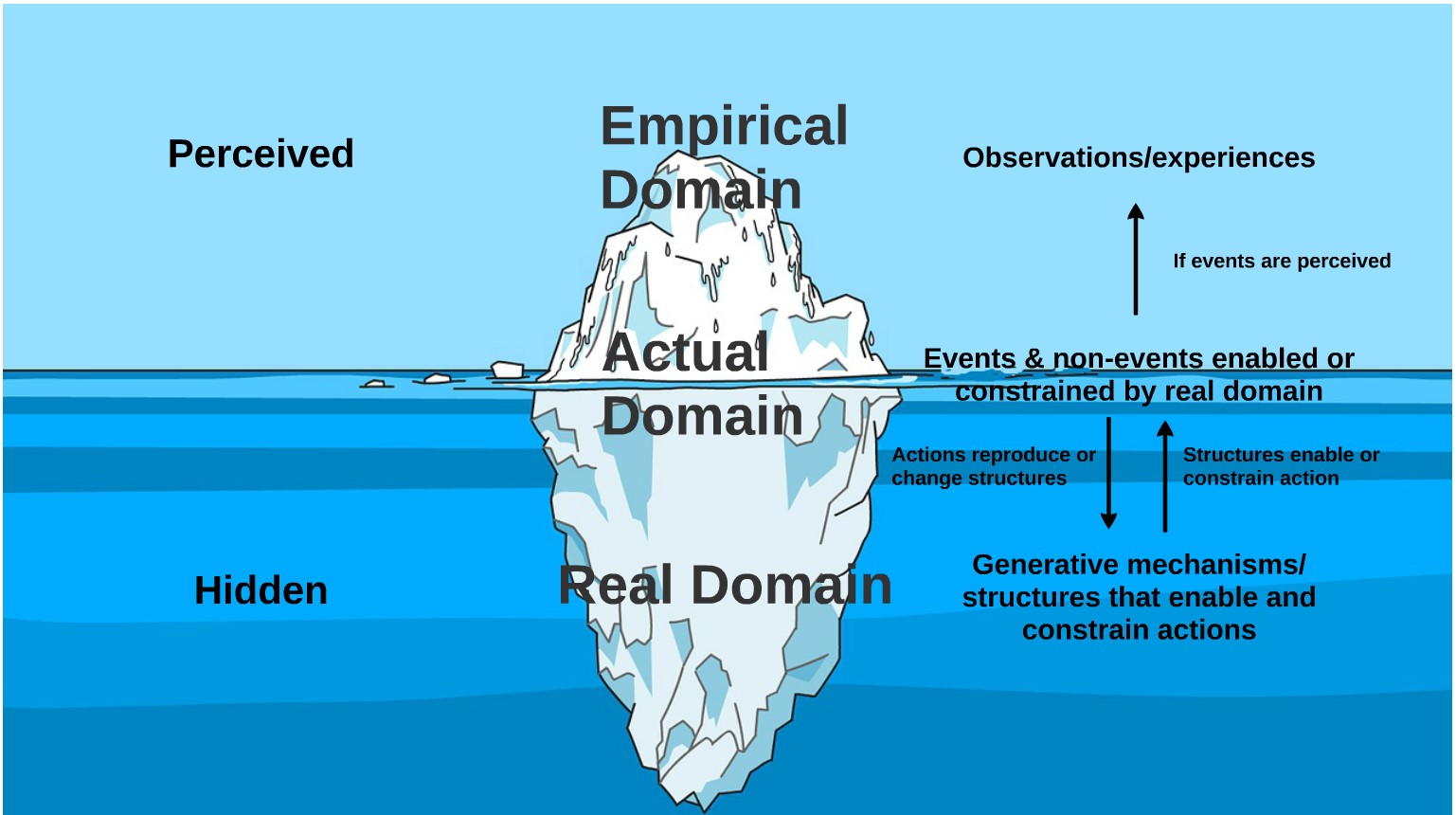

The following figure depicts the relationship between these three layers, after which the subsequent sections describe these layers in detail. In brief, the real domain contains social structures and generative mechanisms (we’ll discuss what those are in a moment). These structures distribute resources and authority to different people within a social setting, which in turn enables or constrains the actions they can take. These actions (or lack of action) create events (or non-events) in the actual domain. The actions people take tend to either reproduce structures back in the real domain or change those structures. Sometimes an event happens, and no one notices. If an event is observed, however, that observation/experience occurs in the empirical domain. Let’s dig into the details of these layers and flesh them out.

Key Takeaways

Critical realism envisions three layers of social reality

- The real domain

- The actual domain

- The empirical domain

The Real Domain

Within the real domain, social structures exist that enable or constrain people’s actions within a social setting. Though the word ‘structure’ gives the impression of something physical, like the structure of a house, social structures are, in fact, intangible.[4] Structures, for example, may include the policies and procedures staff follow during their workday or the education levels within a labor pool from which a company hires employees.[5][6]

Social settings are complex, open systems. This complexity is reflected in the web of structures governing these settings. Different structures may contradict each other–for example, structures influencing professional conduct within a work environment may moderate structures of racism.[7][8] The time between when a structure influences a person’s behavior and when that person chooses to act may make it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relations between the structure and action.[9] At times, there may exist forces that hide the role another structure had in generating an event,[10] or there may exist structures that exist but lie dormant until certain circumstances activate them.[11]

An earlier section asked why, since teacher-student relations are the product of human imagination, are you unable to change the nature of this relation when you dislike a class. The philosophy of critical realism would argue the answer lies in the structures governing our education system. Structures enable and constrain action. These structures constrain you from unilaterally changing the roles, responsibilities, and authorities inherent in the teacher-student dynamic of our education system. The following section describing the actual domain will introduce an exploration of how these structures, though intangible, have the force to prevent you from changing the education system on a whim. Later chapters of this textbook discussing power will then elaborate on how societies imbue intangible structures with the force to control behavior.

Exercises

There are countless structures active in society. Consider a social setting with which you are familiar. This setting could include, for example, your workplace, a sports team you play with, one of your classes, a religious organization you belong to, and so on. Reflect on the activities of that group. Who does what? How do they do it? What is your role in the group?

- Reflect on the definition of structures. What are some of the structures that enable people to take the actions they do in the social setting you have chosen? What structures constrain the actions people might want to take?

- Think broadly about what enables and constrains action in the social setting you have chosen. Are there policies and procedures that determine who can do what? Traditions? Culture? Does gender, ethnicity, age, education, wealth, or other factors influence who can take what actions?

- Consider how these structures enable and constrain action. To do this, start by considering an action someone is unable to take (for example, a woman may want to join an all-male hockey team, but is not allowed). What happens they try to do something they are forbidden from doing? What, specifically, prevents their action? Likewise, consider an action someone is allowed to do in a social setting (for example, the head coach may determine the drills the team performs during practice). What is it that allows them rather than someone else to take those actions?

- The more detailed you can get with your answers to these questions, the stronger your understanding of social structures will be.

Key Takeaways

- The real domain is the deepest layer of social reality

- The real domain contains structures

- Structures are those forces that enable or constrain action

The Actual Domain

Within the actual domain, individuals perform actions (or refrain from performing actions) leading to events (or non-events). The complex web of structures within the deeper real domain governs the actions individuals perform in the actual domain. Here is where things get interesting.

So far, this text has defined structures as intangible elements of social systems that enable or constrain action. This definition creates the illusion that individuals are ‘locked into’ the roles the social system assigns to them. That is, if you hold a position in a social network in which the prevailing structures of that system enable you to perform a specific action, then you will take that action. If the structures prevent you from taking that action, then you will not act. Remember, though, that structures are intangible. They are the product of human imagination. Money, for example, is a social structure enabling you to buy stuff. Money, however, only has the power to purchase things if enough people in the social system agree that it does. If enough people stop accepting cash in exchange for stuff, then money loses its power to buy things.

In other words, even though structures enable and constrain action, it is our actions that create, maintain, and change structures[12] The structures of our social system govern the actions available to us, but we have agency. We can use our agency to choose activities that reproduce the system’s structures or change them.

Though we can act to change structures, doing so is hard. Consider an extreme example–national borders. The borders between countries are socially constructed structures. Though we can act to change a nation’s borders, doing so usually involves armed conflict between nation-states. Structures are backed by systems of power that may undermine your attempts to change them.

More often, we choose actions that maintain the structures of our social system. That is, after all, what makes societies stable. When you are a student, you may have a teacher who assigns you a research paper. You will likely choose to complete that assignment to the best of your abilities. That compliance reinforces the structures of the educational system. Through your actions, you are contributing to the social reality where teachers assign research papers, and students complete them. If you have children of your own, you will likely teach them how to behave in a classroom, perpetuating those social structures into the future.

Exercises

In the exercise at the end of the previous section, you identified structures within a social setting. Using that same social setting, consider the actions people take (or choose not to take).

- Consider the structures you identified in the previous exercise. Then, think of specific examples of actions you or others took in that social setting. In what way did those actions reinforce the structures you identified?

- Has anyone ever tried to change the structure of the social setting (for example, changing the entrance criteria for a sports team, changing how shifts are assigned at work, and so on)? What specific actions did they take to make the change? How did others in the social setting respond? Did they successfully implement their change? If no, what did people do to prevent the alteration? If yes, what actions were vital to successfully achieving the change?

Key Takeaways

- The actual domain is the middle layer of social reality

- Actions, events (or non-events) occur in the actual domain

- Structures in the real domain govern the actions available to people

- The actions people perform either reproduce or change structures in the real domain

The Empirical Domain

In the empirical domain, individuals have observations and experiences. These observations and experiences are a result of actions and events in the actual domain. The empirical domain constitutes the everyday experiences of our lives, such as the good day at work or the frustrating meeting you had with your boss. We seldom look beneath these experiences to see what drives them. Through the application of a critical realist framework, however, we can peer deeper into our social environment to gain insights into what is creating the experiences we have.

Key Takeaways

- The empirical domain is the surface level of social reality

- The empirical domain contains observations/ experiences caused by actions in the actual domain

How Does Critical Realism Help us Understand Organizations?

Let’s look at an example to see the utility of the critical realist framework for understanding organizations.

An Example of Applying a Critical Realist Framework: National Manufacturing Characteristics[13]

The situation

During the latter part of the Twentieth Century, low-skilled workers and low-value-added processes dominated the British manufacturing industry. British companies competed globally based on low cost. Foreign investments and trade relations led some businesses to try shifting their manufacturing towards high-skilled labor and high value-added processes to make more profits. Companies found making this shift was near impossible.

Recasting the situation through a critical realist lens

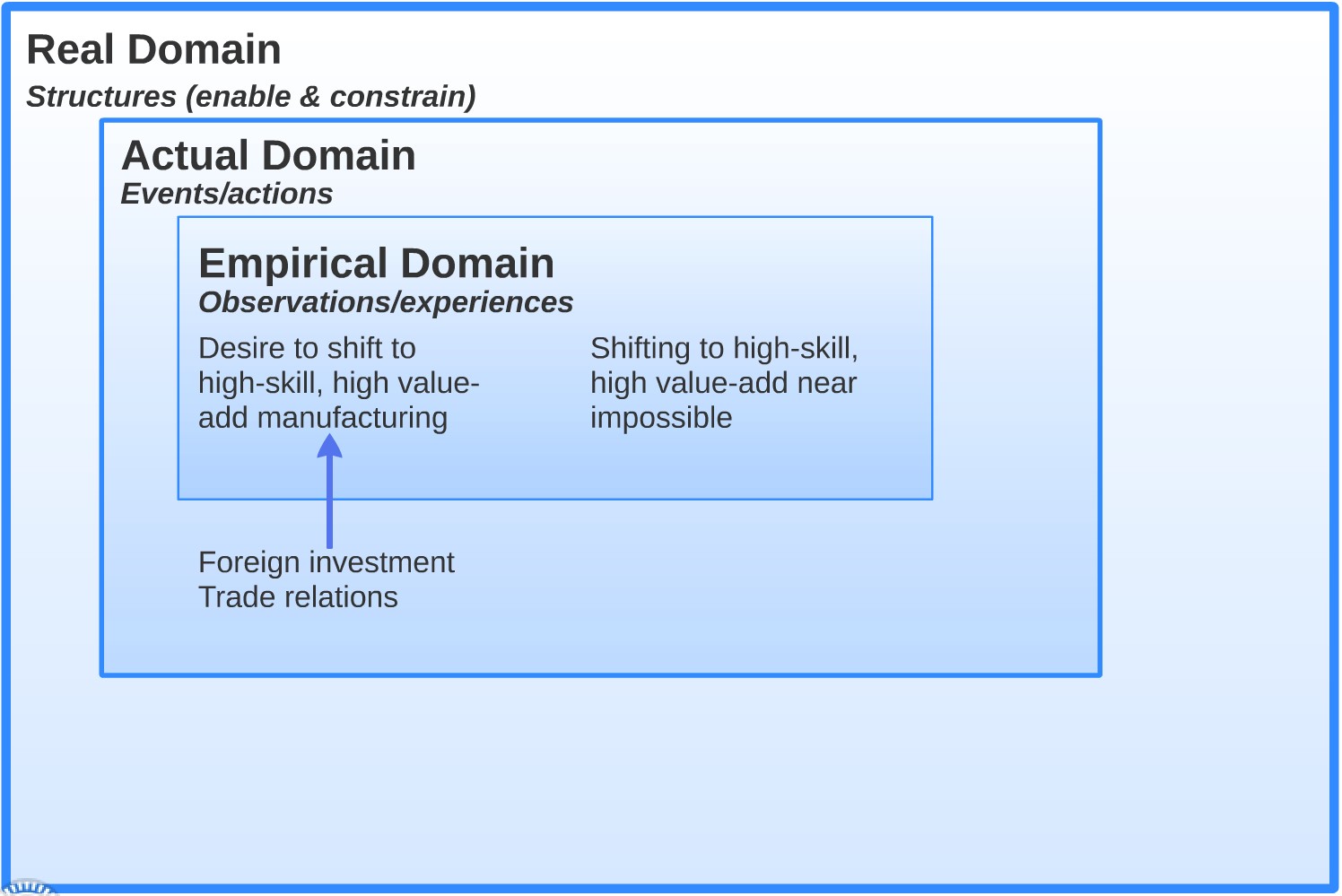

The desire to shift towards high-skilled labor and value-added processes is an experience (empirical domain). This experience was borne out of foreign direct investment and trade relations (events in the actual domain). The difficulty businesses experienced in making this shift was another experience (empirical domain). The following figure diagrams this situation using a critical realist framework.

Why was making this shift so hard? It would seem all a company would have to do is hire highly skilled employees to work with high tech machinery to produce a high-value product. Simple, right? What forces prevented them from making this shift? To answer this, let’s look at the underlying social structures enabling and constraining these businesses ‘ ability to act.

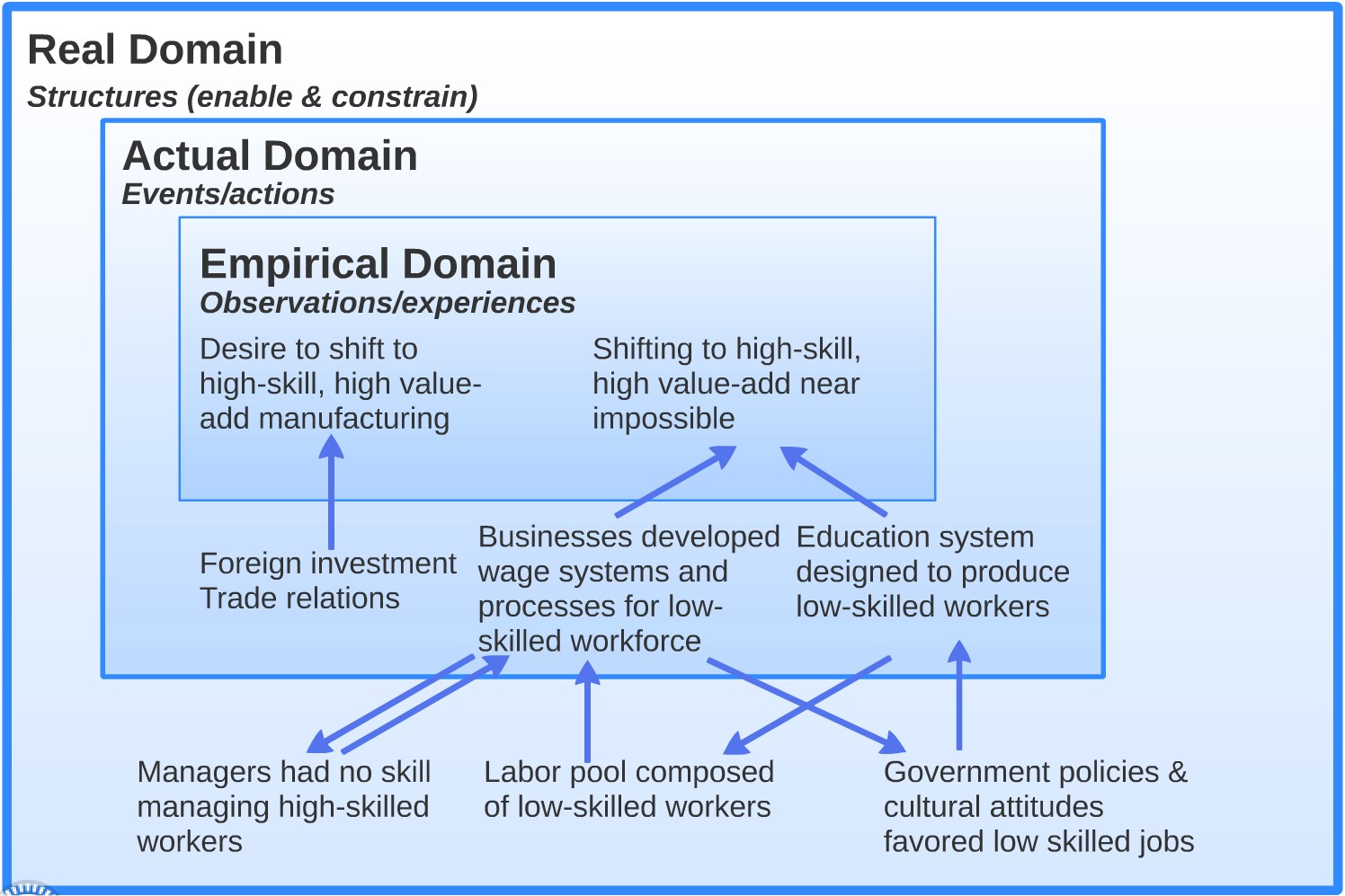

The British labor pool at the time had only low-skilled workers; thus, there were no high-skilled workers to hire (constraining structure). Consequently, managers in these businesses had no experience hiring or managing a high-skilled workforce (constraining structure). Additionally, government policies and cultural attitudes (structures) promoted training systems that produced low-skilled workers (action). Consequently, there was no pool of high-trained workers to draw from (constraining structure). In response, businesses developed wage systems and processes that accommodated this low-skilled workforce (action), which in turn reinforced those constraining structures preventing the industry from moving to high-skilled, high-value work. The following figure diagrams this situation using a critical realist framework.

In the above example, viewing Britan’s attempt to shift to a high-skilled, high value-add workforce through the lens of critical realism shows us why making such a change was difficult. The current system produced and maintained structures which in turn supported and maintained the current system. Those same structures then created constraints on businesses that tried to shift to a different system.

Critical realism, however, does more than identify constraining structures. It also gives insight into what advocates must do to shift to high-skilled, high value-add processes. The above example identified three constraining structures: lack of manager talent, a labor pool devoid of highly skilled workers, and government policies and cultural attitudes. To shift the manufacturing regime to high-skilled, high value-add processes, advocates would have to train managers capable of managing a high-skilled workforce. They would further have to alter the education system to produce high-skilled workers. To do this, advocates would have to act to change government policies and cultural attitudes.

Viewing social systems through a critical realist lens allows us to identify those structures that support the status quo. The insights gained from this framework can tell you what actions you need to take to support the current system–that is, which structures do you need to reinforce and strengthen. Conversely, if your goal is to change a system, the critical realist framework helps you identify what structures you need to alter and where points of resistance may lie.

Key Takeaways

- By gaining insight into the underlying structures of an organization, critical realism provides a framework to understand what actions are possible (and what efforts the organization will resist)

- By understanding these structures, individuals can develop plans to implement desired actions

What Does This Have to do With Organizational Wisdom?

Chapter 1 identified three themes of wisdom:

- Values: Values guide wise action

- Rationality: Knowledge is required but insufficient for wise action

- Power: Wisdom is action-oriented

Under a critical realist framework, values, rationality, and power are structures that enable or constrain actions.[14] Values, for example, inform the ends we find worth achieving and the means we find appropriate to achieve them. By defining the ends we pursue and the methods we use, values enable those actions consistent with our values and constrain actions that oppose them.

Rationality encompasses what we know, how we know it, and how we justify our actions.[15] Rationality, therefore informs action by giving us our understanding of the environment in which we operate. What we know (or think we know) enables some activities while constraining others.

Power is the creative force that organizes social systems and allows them to act.[16] People within social systems (such as organizations) create this power network by distributing resources and authority among its members. Depending on the role an individual fills in the organization, this distribution enables them to perform some actions while constraining them from performing others.

To develop organizational wisdom, individuals need to understand the underlying structures of values, rationality, and power with their organization. They must then use that understanding to develop and enact strategies to achieve desired outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Values, rationality, and power are essential themes of organizational wisdom

- Values, rationality, and power are structures under the critical realist framework

We will begin to gain an understanding of values, rationality, and power in the next three chapters. First, we will explore the values active in organizations. The following chapter will then introduce you to the many forms rationality can take. Then, this textbook turns to an exploration of how power operates in social settings.

In this chapter, you learned:

What critical realism is

- Critical realism is a model of how social systems work

- Critical realism is one of many models of social reality

- This text focuses on critical realism because it has utility in conceptualizing forces governing organizational action

The layers of social reality envisioned by critical realism

- The real domain is the deepest layer of social reality

- The real domain contains structures

- Structures are those forces that enable or constrain action

- The actual domain is the middle layer of social reality

- Actions, events (or non-events) occur in the actual domain

- Structures in the real domain govern the actions available to people

- The actions people perform either reproduce or change structures in the real domain

- The empirical domain is the surface level of social reality

- The empirical domain contains observations/ experiences caused by actions in the actual domain

How critical realism helps us understand organizations

- By gaining insight into the underlying structures of an organization, critical realism provides a framework to understand what actions are possible (and what efforts the organization will resist)

- By understanding these structures, individuals can develop plans to implement desired actions

The relation between critical realism and organizational wisdom

- Values, rationality, and power, the three major themes of organizational wisdom, are structures under the critical realist framework

- Frank, A. W. (2012). The Feel for Power Games: Everyday Phronesis and Social Theory. In B. Flyvbjerg, T. Landman, & S. Schram (Eds.), Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis (pp. 48–65). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Ackroyd, S., & Fleetwood, S. (2000). Realism in Contemporary Organisation and Management Studies. In S. Ackroyd & S. Fleetwood (Eds.), Realist Perspectives on Management and Organisations (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Routledge. ↵

- Bhaskar, R. (1978). A Realist Theory of Science. New York, NY: Harvester Press. ↵

- Tsoukas, H. (1994). What is Management? An Outline of a Metatheory. British Journal of Management, 5(4), 289–301. ↵

- Costello, N. (2000). Routines, Strategy and Change in High-technology Small Firms. In S. Ackroyd & S. Fleetwood (Eds.), Realist Perspectives on Management a (pp. 161–180). New York, NY: Routledge. ↵

- Rubery, J. (1994). The British Production Regime: A Societal-Specific System? Economy and Society, 23(3), 335–354. ↵

- Ferguson, K. E. (1994). On Bringing More Theory, More Voices and More Politics to the Study of Organization. Organization, 1(1), 81–99. ↵

- Porter, S. (1993). Critical Realist Ethnography: The Case of Racism and Professionalism in a Medical Setting. Sociology, 27(4), 591–609. ↵

- Tsoukas, H. (1994). What is Management? An Outline of a Metatheory. British Journal of Management, 5(4), 289–301. ↵

- Ackroyd, S., & Fleetwood, S. (2000). Realism in Contemporary Organisation and Management Studies. In S. Ackroyd & S. Fleetwood (Eds.), Realist Perspectives on Management and Organisations (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Routledge. ↵

- Pratten, S. (1993). Structure, Agency and Marx’s Analysis of the Labour Process. Review of Political Economy, 5(4), 403–426. ↵

- Reed, M. (1997). In Praise of Duality and Dualism: Rethinking Agency and Structure in Organisational Analysis. Organization Studies, 18(1), 21–42. ↵

- Rubery, J. (1994). The British Production Regime: A Societal-Specific System? Economy and Society, 23(3), 335–354; adapted by Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Townley, B. (2008). Reason’s Neglect: Rationality and Organizing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. ↵

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Toronto: Random House. ↵

In the critical realist framework, the real domain is the deepest level of social reality. The real domain contains social structures that enable or constrain action.

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

A system that has an effect on and is affected by the outside world.

In the critical realist philosophy, the actual domain is the layer of social reality in which events (or non-events) occur.

The capacity for individuals to act independently and with free will.

In critical realist philosophy, the empirical domain is the highest layer of social reality where people observe and experience the actions and events that occurred in the actual domain.