9 Creating Action in Organizations Part 2 – Rationality and Power

Brad C. Anderson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn:

- How rationality enables and constrains action

- How individuals may overcome the constraining nature of social structures

- How rationality and power interact

This chapter explores how rationality works as a social structure to enable and constrain actions. It then explores how people can overcome their constraining effects. Then, this chapter presents a discussion of how rationality and power interact.

Rationality as Social Structures

As discussed in Chapter 3, rationality is a social structure that enables and constrains actions. The following sections first look at the ways rationality enables action, followed by a discussion of how they constrain.

Rationality Enables Action

Chapter 5 described rationality as the process through which we assess our environment, make decisions and evaluate social interactions. By applying various forms of rationality, we build our understanding of the world and decide how to operate within it. Rationality, thus, enables actions through two mechanisms. First, it justifies actions; second, through bureaucratic rationality, it organizes our activities.[1]

Rationality Justifies Action

Rationality enables actions as it is the means through which we justify our behaviors and convince members in our social group to do certain things. We want others to perceive that we are rational, and thus we choose actions that create that perception.

Considering the Seniors Program from Chapter 7, for example, the fellowship used technocratic rationality to demonstrate their intervention measurably improved the frailty in a seniors population. Through the study they performed, they learned how to delay frailty’s onset. They then used those results to convince healthcare managers and physicians to adopt the program.

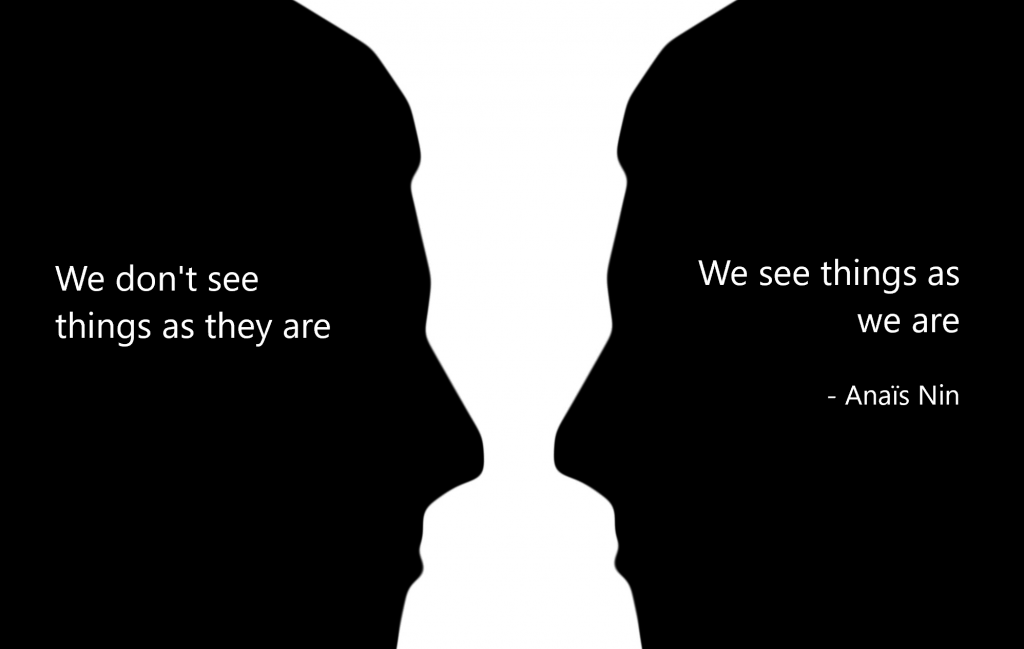

Moreover, interviews with the fellowship surfaced other ways rationality enabled action.[2] The fellowship noted that when discussing the Seniors Program with members of management, many managers were approaching the age of the population targeted by the program. That is, the Seniors Program targeted pre-frail seniors, and the managers of the BC Health Authority were getting to the age where they started to think they might be pre-frail seniors. This realization led some managers to support the program’s spread in the healthcare region. This is an example of emotional rationality. The managers’ sense of affiliation with the target population gave them feelings of, perhaps, fear, empathy, compassion, and so on. These feelings, in turn, led them to support the fellowship’s continuing efforts. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Bureaucratic Rationality Organizes Action

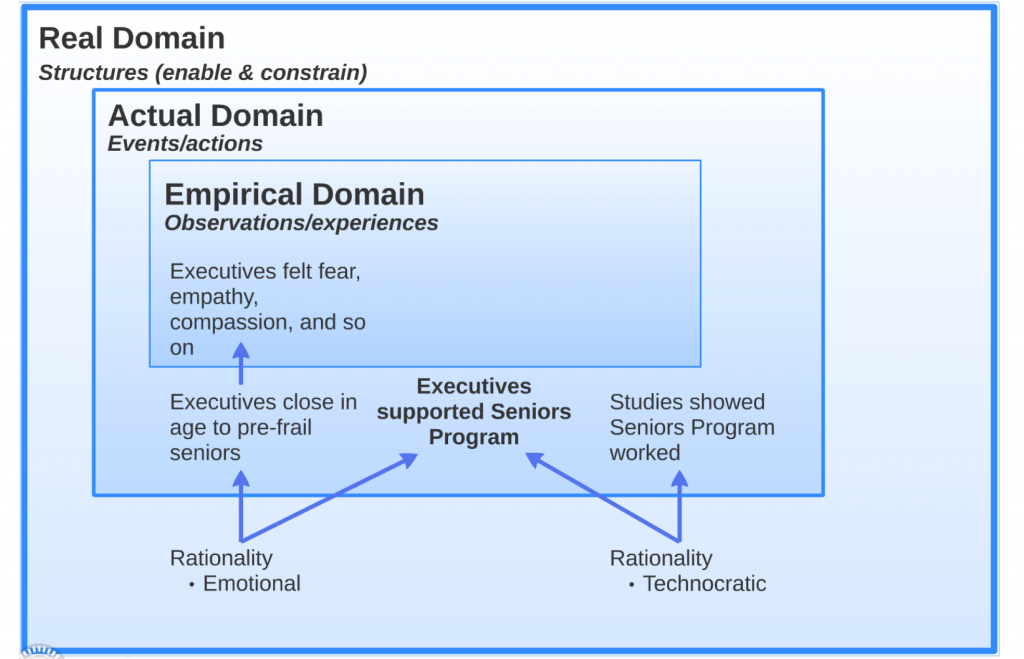

Bureaucratic rationality plays an important role in enabling action. Recall from Chapter 5 how bureaucratic rationality defines how organizations do things. It does this through the creation of documents, boundaries, rules, processes, and procedures and roles. Organizations, thus, enable actions that comply with these bureaucratic structures. Importantly, it is through the creation of new bureaucratic structures that the organization undertakes new actions.

The development of the Seniors Program in Chapter 7 showed an example of this. The Project Charter documented the details of the collaboration between the Foundation and the BC and Nova Scotian Health Authorities. All participating organizations signed this document, committing themselves to form a team that attended the Training Fellowship. It was through this fellowship the Seniors Program came into existence.

The Project Charter embodied several bureaucratic rationalities.

- It was a document that codified the terms of the Seniors Project and embodied the agreement between all participating organizations to collaborate.

- It established boundaries by defining the scope of the project.

- It specified the rules of the collaboration by, for example, defining the process through which a party could end the partnership.

- It listed processes the fellowship followed, including decision-making activities.

- It identified key procedures and roles that stakeholders would perform throughout the program’s life.

Through the creation of the Project Charter, stakeholders produced new bureaucratic structures within their organizations. These new bureaucratic structures were the means through which stakeholders incorporated the activities needed to bring the Seniors Program to life into their organizations.

It was through bureaucratic rationality that the fellowship translated the Seniors Program from an idea into action the organization performed. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Rationality Constrains Action

In the same way that rationality justifies an action, it can also argue against it. Similarly, though bureaucratic rationality provides the organizational structure for an activity, these structures can also stifle attempts to act.[3]

Rationality Argues Against Taking Action

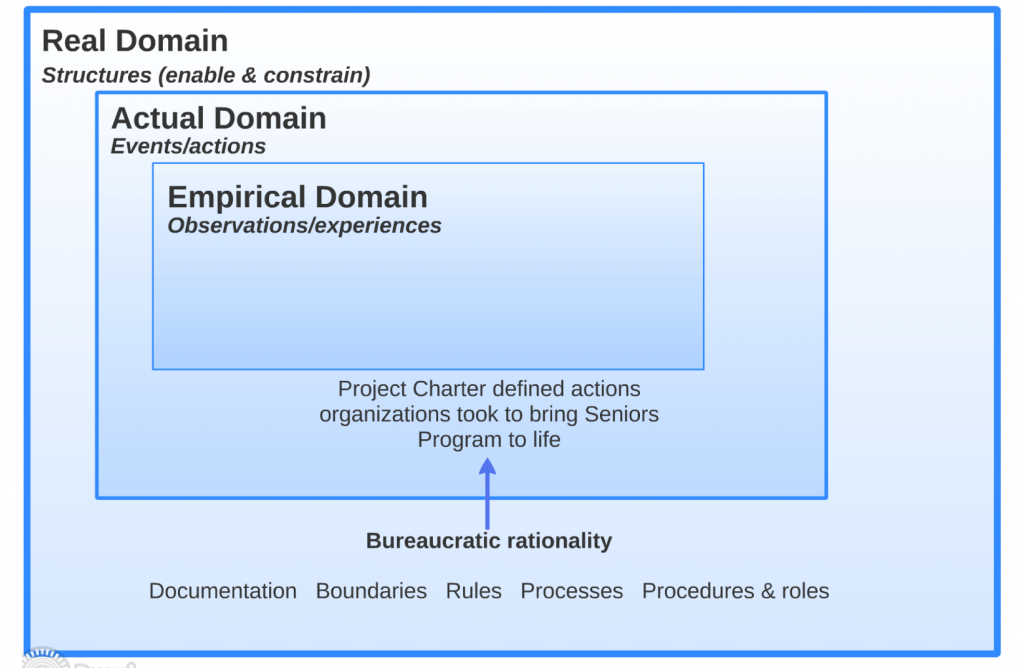

There are times when rationality leads us to conclude an activity is undesirable. Recall from Chapter 7 how the fellowship approached physicians and asked them to adopt the Seniors Program. These doctors used economic rationality and concluded it would be financially unfeasible for them to do so.

Moreover, the fellowship initially wanted to develop a single intervention that the BC and Nova Scotian health authorities would implement. Differences in target patient populations and healthcare infrastructure prevented this, forcing the fellowship to make modifications for each region. This is an example of contextual (cultural) rationality preventing a unified approach.

Recall also how the fellowship wished to have the elderly perform a specific set of physical activities endorsed by research. The health of patients varied, however, and the fellowship had to modify prescribed physical activities to account for individual capabilities. In this way, the body rationality of individual patients prevented a unified approach. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Bureaucratic rationality can stifle action

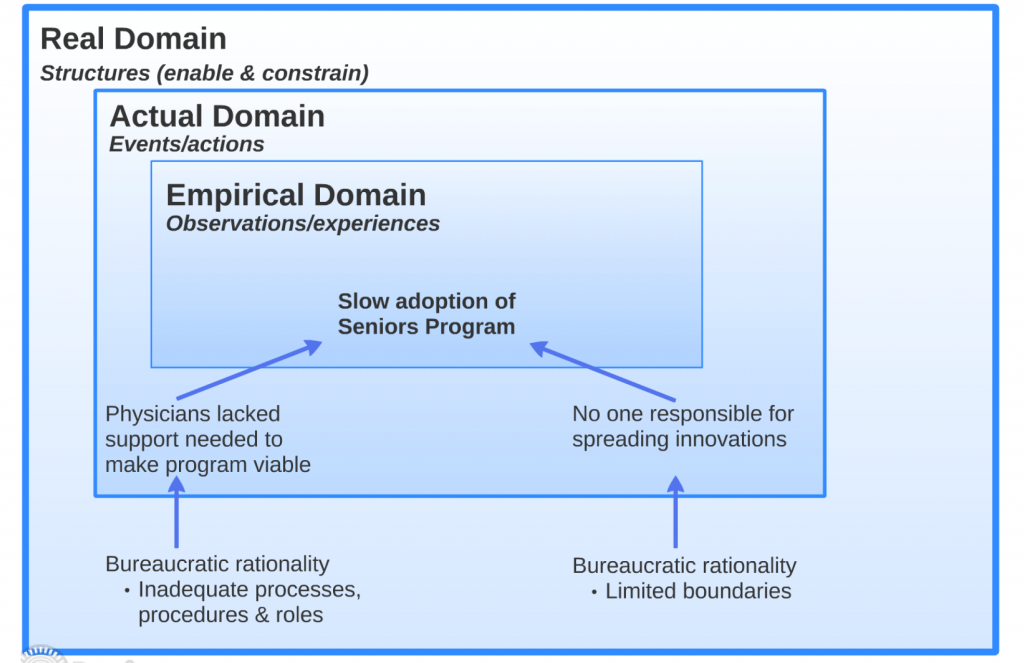

A lack of appropriate bureaucratic structures can constrain individuals’ ability to act. As described earlier, physicians’ economic rationality prevented them from adopting the Seniors Program. Having help from other healthcare professionals, such as physiotherapists or nurse practitioners, could have reduced the cost pressures facing doctors. If this work were distributed, however, full implementation of the Seniors Program would require the sharing of the patient’s records among all these healthcare professionals. The IT and other communications infrastructure to achieve this level of coordination were not in existence at the time of the program’s development. Thus, a lack of appropriate processes, procedures, and roles (that is, bureaucratic rationality), constrained physicians’ ability to adopt this program.

Likewise, bureaucratic rationality limited the fellowship’s ability to spread the Seniors Program outside of the region the BC Health Authority administered. Managers within health regions were responsible for overseeing healthcare within their geographic area. They had no mandate to promote the spread of innovations outside of their region, which limited support for the fellowship as they sought to expand their program across Canada. This speaks to the bureaucratic rationality of boundaries. Bureaucratic rationality ‘bounded’ the scope of managers’ responsibility to a geographic region. The healthcare system’s bureaucratic structures had failed to assign responsibility for spreading innovations nation-wide to anyone. Thus, when the fellowship needed support to spread the Seniors Program nationally, they found that support lacking. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Key Takeaways

- Rationality enables action

- Rationality justifies actions

- Bureaucratic rationality gives action structure

- Rationality constrains action

- Rationality argues against actions

- Bureaucratic rationality can stifle activity

Acting to Overcome Constraining Structures

As discussed in Chapter 3, even though structures enable and constrain activity, it is through our choices that we either reinforce or change structures. Individuals may, therefore, choose actions in attempts to overcome constraining structures.

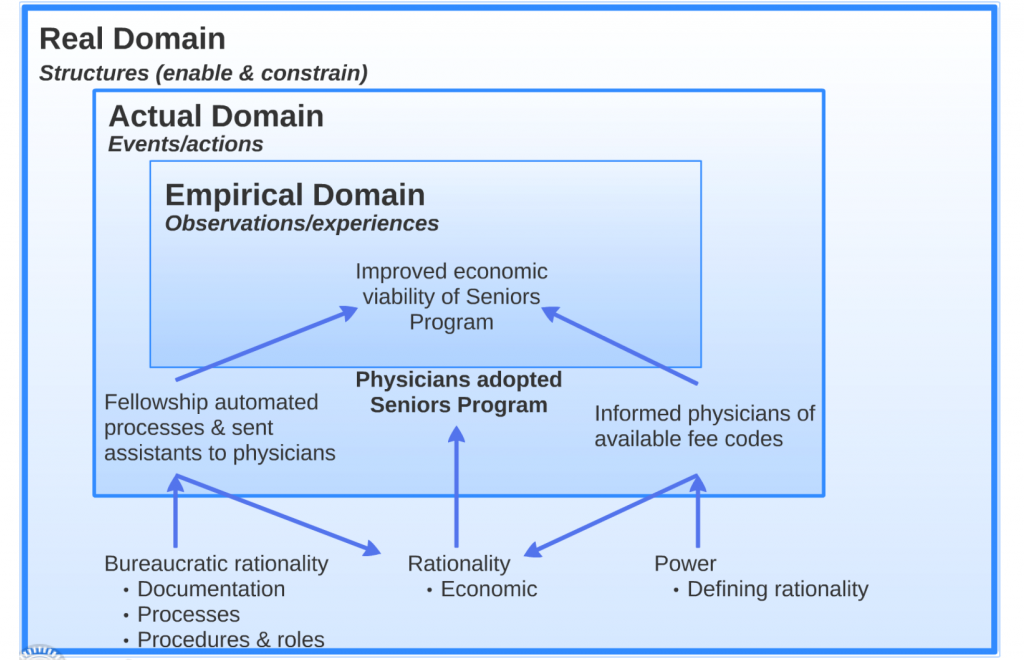

For example, through economic rationality, physicians concluded that adopting the Seniors Program was financially unfeasible. The fellowship, in turn, developed electronic documentation to automate the doctors’ work in an effort to reduce costs–that is, they developed new bureaucratic rationality (documentation & processes) to change clinics’ economic rationality.

Additionally, they informed physicians of fee codes that were available to reward some of the work they would do if they adopted the Seniors Program. This is an act of defining rationality to, again, change the clinics’ economic rationality. The BC Health Authority further provided personnel to assist clinics, thus using bureaucratic rationality (procedures & roles) to support the program’s spread. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Key Takeaways

- Individuals may use different forms of rationality to overcome constraining structures

Rationality and Power

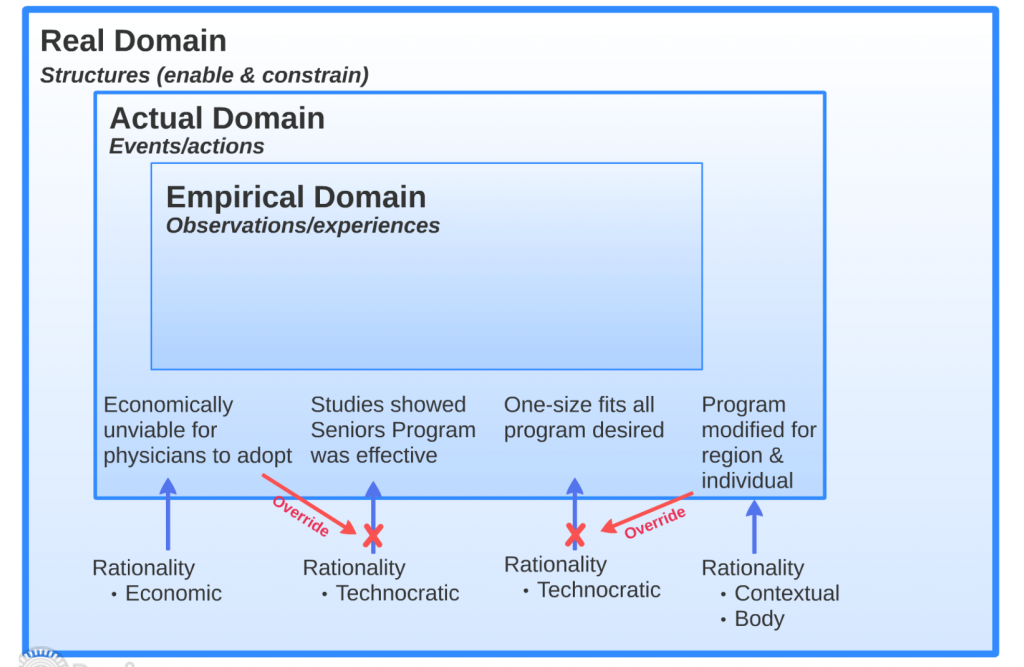

As you read the above sections of rationality’s ability to enable and constrain action, you may have noticed the influence of power. Indeed, the relationship between rationality and power is strong. This relationship catches many readers by surprise. Students of Western societies’ education systems are taught the tools of instrumental-rationality. Consequently, we see rationality as objective truth, something ‘out there,’ unchanging and separate from human experience, something beyond the ‘corrupting’ influence of power.

Though there may be objective truths ‘out there,’ we live here in the social world. Thus, it is the reality of the social world with which we must contend. Rationality gives us our understanding of a situation, which informs our behaviors. We use it to justify our actions and convince others to act how we wish. Rather than being objective, people’s interests shape rationality.

Through my actions, informed by what I think is rational, I change the world. If I can convince you a specific activity is reasonable, I can change your behavior. My ability to define what you consider appropriate evidence combined with my ability to influence how you interpret that evidence gives me the ability to affect what you think is rational. By defining what you perceive as sensible, I influence your actions. Rationality is, thus, inextricably linked to power.[4]

This relation between rationality and power manifests in several ways. It is through the exercise of power that rationalities can enable or constrain. Individuals and groups with the capacity to define rationality have the power to influence the actions of large groups of people. Finally, it is through bureaucratic rationality that people translate power into action within an organization. Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Power Gives Rationality the Force to Enable or Constrain ctions

For rationality to enable or constrain activities, people must also exercise power.[5] For example, it was the CEO’s authority to bind the BC Health Authority to the Seniors Program by signing the Project Charter. It was his signature that gave that document force. His authority to bind the organization to a course of action is an expression of power in organizations. Through entering into a collaboration, the CEO produced power relations through which the Seniors Program came into existence.

Bureaucratic rationality, as expressed in the Project Charter, enabled the fellowship to create the Seniors Program. Still, it was power vested in the CEO that gave bureaucratic rationality the force to create action.

Likewise, economic rationality was a constraining structure in that it led physicians to refuse to adopt the Seniors Program. What gave them the authority to refuse to perform an intervention that was of great benefit to seniors?

The bureaucratic structures of the healthcare system gave authority to doctors to choose what medical interventions they prescribed to patients. When physicians refused to adopt the Seniors Program, the fellowship–and even the CEO of the health authority–lacked the authority to overrule them. Such bureaucratic authority is an example of coercion.

The ability of doctors to chose which interventions they prescribe is an example of power in the organization. The fellowship sought to use their power against the organization to influence physician behavior but lacked the authority to force them to do so.

It is the distribution of power within a social system that gives rationality the ability to enable or constrain actions.

Power Gives Rationality the Capacity to Overcome Constraining Structures

The above examples showed the fellowship using rationality to overcome constraining structures. For example, you saw them use bureaucratic rationality (by developing electronic forms to automate processes) to overcome resistance caused by the financial costs to doctors of adopting the Seniors Program. For these bureaucratic rationalities to work, the fellowship had to exercise power.[6]

For example, they had to connect with experts capable of developing electronic documents (production of power relations). They had to find doctors willing to incorporate these electronic forms into their practice (production of more power relations). The fellowship also had to secure funding to finance the process of developing these forms (production of yet more power relations). To create these relations, the fellowship used episodic and three-dimensional forms of power by paying people for work and convincing them to cooperate).

Power Gives Rationality the Ability to Define Reality

When you use the power tactic of defining rationality, even for something as simple as convincing a friend about the merits of a movie you like, you are defining reality. The more power an individual or group has, the more they can establish what people perceive as the truth. Through this process, people influence the actions of others.[7]

Defining rationality is achieved by effectively framing the debate in people’s minds. People and groups that do this well can influence what others consider appropriate evidence. They further guide people in how they should interpret that evidence. Some groups and individuals may possess the ability to suppress some forms of evidence while amplifying others. These actions can be done maliciously with an intent to manipulate. It can also be done productively, for it is the way we construct the understanding of our world needed to create collective action.

When you write a report for your boss, client, or teacher, you choose what information to include in that report, what that information means, and what to exclude. You may perform a scientific experiment to learn an objective truth about the universe, but you choose what research question to ask, how you will answer that question, and which issues to ignore. You define rationality, too. We all do. Defining rationality is one of the most common ways we all exercise power in social settings.

It is Through Bureaucratic Rationality That Power Manifests

Okay, what does that even mean?

In the above examples, you may have noticed how bureaucratic rationality always seemed to have a role in mediating the use of power. This textbook is going to introduce a fancy word: reify. To reify something is to turn something intangible into something a bit more concrete.

Money, for example, is an intangible concept. It is an idea, something we humans imagined. Yet, in the absence of money, your ability to obtain food or shelter is limited. You may starve and possibly die. These are very concrete effects. Somehow we turned money, this intangible figment of our imagination, into something with a very tangible impact in the real world. Through some mechanism, we reified money.

Power is also an intangible thing. You cannot drop power on your toe or put it in a gift box as a present to someone. Yet, through power, we create civilization. Through what mechanism do we reify power?

We reify power through bureaucratic rationality.[8][9] Let’s look at some examples to explain.

Do you think a janitor working in the BC Health Authority could negotiate an agreement with the Nova Scotian Health Authority to create a partnership? No, of course not. But the CEO could, as he did when he signed the Senior Program’s Project Charter. What is it that allows the CEO to sign agreements on the company’s behalf but prevents a janitor from doing the same?

The answer is bureaucratic rationality. Procedures & roles, boundaries, rules, and processes govern which positions in the organization have the authority to do what. These structures are codified in documents, such as job descriptions, terms of incorporation, company charters, and so on.[10][11]

Well, who created the bureaucratic rationalities that govern the BC Health Authority? In Canada, provincial governments establish health authorities. When they created these authorities, they developed the bureaucratic rationality through which they operated. Well, who gave the provinces this authority? The bureaucratic rationality documented in the Canada Health Act adopted by the Government of Canada. And so on. Organizations (and society) structure themselves using bureaucratic rationalities identifying who can do what and how they do it.

Here is the important thing to note. When you want your organization to take a certain action, you achieve this by creating new structures of bureaucratic rationality to govern that action. For example, when physicians refused to adopt the Seniors Program due to its lack of financial viability, the fellowship looked for ways to reduce the doctor’s costs of implementing it. They did this by creating new documents (electronic records) and processes (automating functions). They convinced the organization to redefine procedures & roles (by having personnel assigned to clinics to assist physicians).

The creation of these bureaucratic structures was mediated (yet again) by bureaucratic rationality. To successfully drive their organization to act, the fellowship possessed significant insight into the bureaucratic rationality governing the BC Health Authority. They understood how it worked and how it made decisions. The fellowship used that insight to create the new bureaucratic structures that led to the desired action.

In short, to create organizational action, you need to create structures of bureaucratic rationality that enable that action. Doing this requires that you possess insight into the current bureaucratic rationality governing the organization through which it makes and implements decisions.

Official Versus Unofficial Bureaucratic Rationalities

You will find most organizations have a formal bureaucratic structure. That is, they will have codified policies and procedures of how the organization is supposed to run. Then, they will have the unofficial system of how it actually runs.

For example, if an instructor in a university wanted to create a new course, there is a formal process through which they design the course and have the institution approve it for use. Underneath that system, however, are rationalities that may be less well documented.

The individuals working in specific departments that must approve the new course may have certain interests they wish to see reflected in any new class they approve. People have to learn about these requirements on their own.

Likewise, because a course is approved is no guarantee that the school will ever offer it. Administrators schedule classes, and they must balance the needs of different programs and student demand with the school’s finite supply of classrooms and teachers. These choices are often left to administrators’ discretion. There may be no formal system of how they determine what classes to run.

To effectively create the desired action in your organization, you must learn not only the official bureaucratic rationalities governing the institution but the unofficial ones as well. As the next chapter discusses, you learn this through developing your institutional and contextual (cultural) rationality about your operating environment.

Key Takeaways

- Power gives rationality the force to enable or constrain actions

- Power gives rationality the capacity to overcome constraining structures

- Power gives rationality the ability to define reality

- It is through bureaucratic rationality that power is reified.

- In organizations, bureaucratic rationality may take official and unofficial forms

- You learn bureaucratic rationality by developing your institutional and contextual rationality

Rationality and Power as Social Structures

Structures shape organizations’ actions. Through our actions, we reinforce those structures, creating stability, or we attempt to change them. The above chapter explored some ways through which the structures of rationality and power operate in organizations. Through the above insights, we can become more conscious about the systems that govern social systems, which will allow us to be more effective in the actions we choose to take.

Social systems such as organizations can be complicated as inter- and intra-organizational groups each act to advance their interests. Taking action often requires a coordinated effort from multiple groups. Resistance from other groups is a constant threat with which we must contend. The next two chapters discuss how we can combine values, rationality, and power to create wise organizational action.

In This Chapter, You Learned

How rationality enables and constrains action

- Rationality enables action

- Rationality justifies actions

- Bureaucratic rationality gives action structure

- Rationality constrains action

- Rationality argues against actions

- Bureaucratic rationality can stifle action

How individuals may overcome the constraining nature of social structures

- Individuals may use different forms of rationality to overcome constraining structures

How rationality and power interact

- Power gives rationality the force to enable or constrain actions

- Power gives rationality the capacity to overcome constraining structures

- Power gives rationality the ability to define reality

- It is through bureaucratic rationality that power is reified

- In organizations, bureaucratic rationality may take official and unofficial forms

- You learn bureaucratic rationality by developing your institutional and contextual rationality

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago, United States: The University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago, United States: The University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Townley, B. (2008). Reason’s Neglect: Rationality and Organizing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. ↵

- Smith, D. E. (2001). Texts and the Ontology of Organizations and Institutions. Studies in Cultures, 7(2), 159–198. ↵

- Townley, B. (1993). Foucault, Power/Knowledge and Its Relevance for Human Resource Management. Academy of Management Review, 18(3), 518–545. ↵

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

Technocratic rationality assumes the world (including humans) operate according to objective laws of nature. Through the application of the scientific method, practitioners gain an understanding of these objective natural laws, which in turn allows them to optimize systems of human activity.

A form of embodied rationality. Through emotional rationality, we use emotions to communicate within a group the status of its members and the collective as a whole. Internally, our emotions tell us what ends we desire, and the means we are willing to use to achieve them.

Bureaucratic rationality controls how individuals in organizations perform activities by defining and controlling knowledge through documentation, boundaries, rules, processes, and procedures/roles. It is a form of disembedded rationality.

A form of bureaucratic rationality. Bureaucracies use documents to classify and define objects, activities, and people (e.g. job descriptions, employment contracts)

A form of bureaucratic rationality. Bureaucracies define boundaries that classify who is responsible for which activity (e.g. finance department approves spending, teachers administer classroom lectures)

A form of bureaucratic rationality. Bureaucracies use rules to guide behavior and reduce the unpredictability of human discretion (e.g. sales associates must reply to customer e-mails within twenty-four hours)

A form of bureaucratic rationality. Bureaucracies use processes to standardize how individuals perform activities (e.g. the process of taking an order at a coffee shop)

A form of bureaucratic rationality. Bureaucracies use procedures and roles to eliminate unpredictability by defining discrete roles within the organization responsible for different procedures (e.g. the Vice President of Marketing is responsible for overseeing all the company's marketing activities).

Economic rationality is a means through which individuals make utility-maximizing decisions. It is a form of disembedded rationality.

A form of embedded rationality. Contextual (cultural) rationality presumes that what is rational can only be determined from within the social context (that is, culture) in which it occurs.

A form of embodied rationality. Body rationality argues that we gain knowledge through our senses. Experience gained through our senses forms the basis of intuition, which is a fast-act of logical reasoning. It is our intuition that allows us to act in complex situations when we lack the time or data needed to formally process our options.

A tactic of power where one party seeks to shape what others perceive as rational.

Through instrumental-rationality, individuals make objective, logical calculations to achieve goals efficiently, maximize self-interest, or apply rules and laws.

Power in organizations describes the efforts of individuals within an institution's boundaries to affect the structures governing the organization.

Two or more parties take action to form a working relationship with each other.

Coercion is an form of episodic power. It is the use of power to compel another party's compliance when they otherwise would not comply.

Power against the organization describes the efforts of outside individuals or groups to create a change in the structures governing the organization.

Episodic power is the direct exercise of power. It includes coercion and manipulation.

The ability to get what you want by influencing the preferences of others.

To reify something is to make something that is intangible into something a bit more concrete.

A form of embedded rationality. Institutional rationality governs what is rational within a sphere of human activity.

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.