8 Creating Action in Organizations Part 1 – Values and Power

Brad C. Anderson

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn:

- How values enable and constrain action

- How individuals may overcome the constraining nature of social structures

- How values and power interact

Chapters 4 through 6 discussed the structures of values, rationality, and power separately. In reality, none of these elements act in isolation. They are deeply intertwined, and one structure seldom operates in the absence of the others. This chapter explores the relationship between values and power in organizations. The next chapter discusses rationality and power, followed then by a chapter that combines all three.

This chapter first explores how values as a social structure enable and constrain action. It then explores the ways individuals may overcome constraining structures. That conversation leads to a discussion of power as it relates to values. With this road map before us, let us begin with a discussion of values as social structures.

Values as Social Structures

In Chapter 3, this textbook classified values as a social structure. You will recall that structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain action. How, exactly, do values enable certain actions while constraining others? The following sections will first consider values’ enabling nature, after which it will discuss how they constrain other actions.

Values Enable Action

Values enable action through at least two mechanisms. First, they motivate individuals to perform specific actions. Second, the current values of a social system will allow and encourage people to perform activities consistent with those values.[1] Let’s consider each in turn.

Values Motivate action

In Chapter 7’s case study, the fellowship responsible for developing and implementing the Seniors Program faced several hurdles. They had to spend countless hours reading literature and attending conferences to become experts in the field of delaying frailty. Though their CEO supported their efforts, many vice presidents and other senior executives did not. This lack of vice-presidential support led to challenges in obtaining resources and personnel to do the work needed to implement the program. Later, when the fellowship wanted physicians to adopt the Seniors Program, they discovered that the doctors’ inability to bill for their work prevented them from taking up the program.

The fellowship managed all those challenges in addition to their regular duties as managers of a health authority. Their work on the Seniors Program was not a part of their daily job duties. They received no extra pay for their efforts. The fellowship volunteered to take on these tasks. Why?

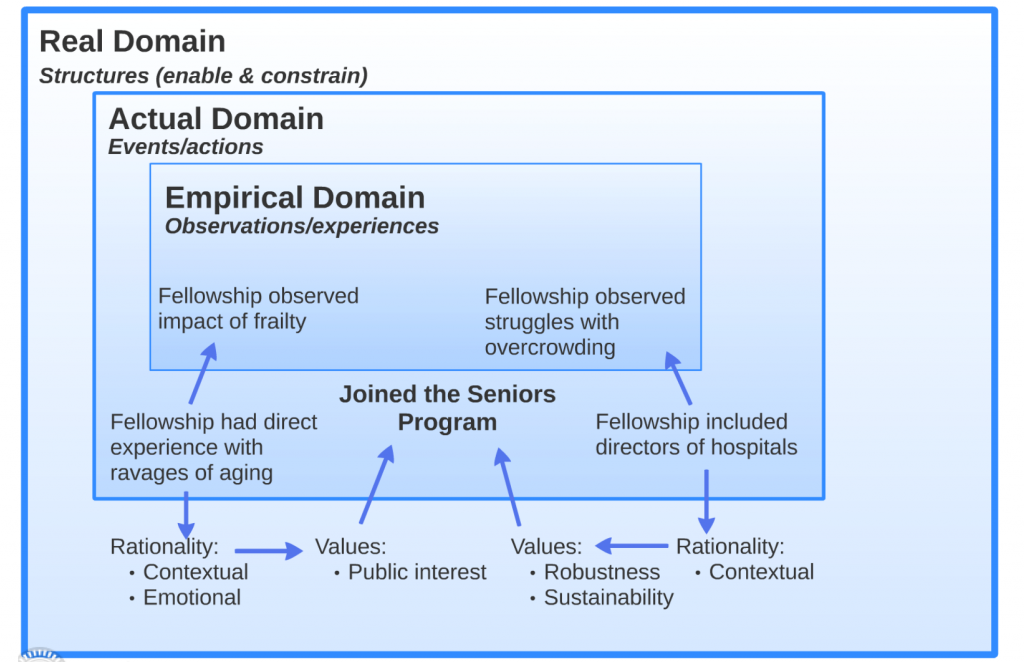

A researcher interviewed the fellowship to learn what motivated them.[2] Without exception, several values drove members of the fellowship

The fellowship included many healthcare professionals who had worked extensively with senior citizens. Some of them had aging parents with failing health. The members of the fellowship had seen first hand the ravages of frailty on the elderly. When they discovered the Seniors Program had the potential to prevent frailty, they were deeply, passionately, committed to bringing the program to life. From the framework for public sector values presented in Chapter 4, the value of public interest drove these people.

Additionally, the members of the fellowship included the directors of hospitals. At the time, overcrowding plagued their hospitals. As the population of the surrounding region aged, they knew demand on hospital resources would increase. They firmly believed the current healthcare system was unsustainable. They reasoned that the longer they could keep senior citizens healthy, the less demand they would place on their hospitals. Using the public sector values framework, this line of reasoning implies values of robustness and sustainability.

Values define the ends we believe are worth pursuing and the means we find appropriate to achieve them. When a value touches you deeply, it motivates you to act.

By giving people the desire to act, values become enabling structures.[3] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Provide Access to Resources Needed to Allow Action to Happen

The above example demonstrated how values motivate individuals. Organizations, however, also possess values of their own. Society creates hospitals, for example, to care for the sick and injured. That is, we create hospitals to pursue the value of public interest. Recall from Chapter 4 that organizations require a multiplicity of values to thrive. Though hospitals’ terminal value may be public interest, we want hospitals to have the capacity to manage the demand for services (value = robustness). We want hospitals not just today, but in the future, also (value = sustainability). We want new treatments to cure diseases that afflict us (value = innovation). And so on.

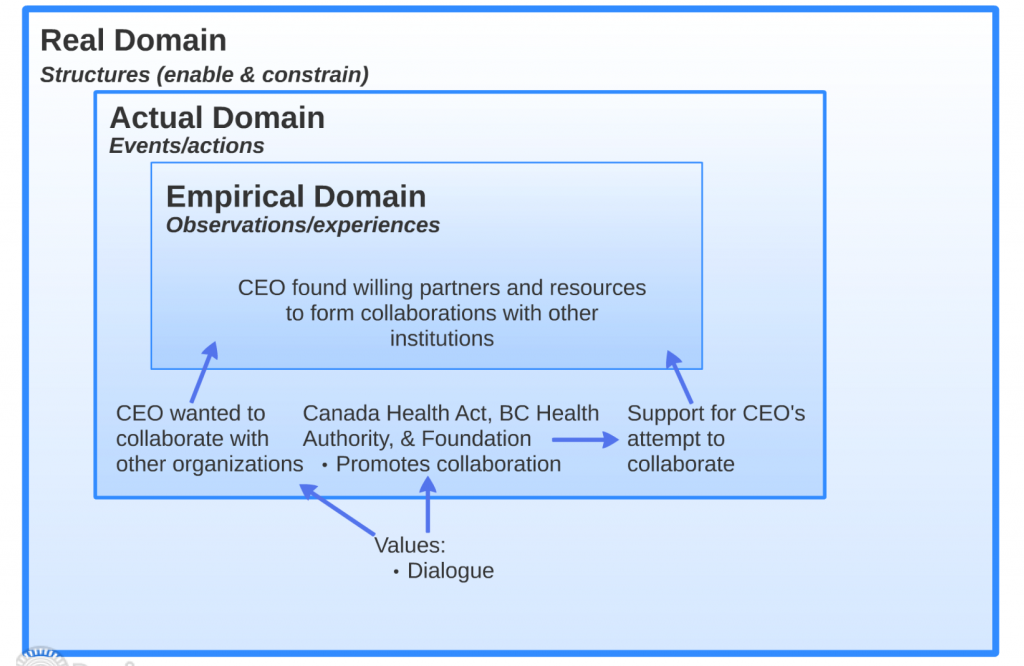

Thus, within the make-up of every organization is a set of values that guide its activities. Members of that organization will find it easier to take actions consistent with those values.

We can see an example of this with the Seniors Program. Recall that the CEO established the Seniors Program through a collaboration between health authorities in BC and Nova Scotia as well as the non-profit organization. These actions reflect the public sector value of dialogue and cooperativeness. When you study the Canadian healthcare industry, you find these values are prominent. The Canada Health Act promotes collaboration among healthcare professionals.[4] Likewise, the mission statements of the BC Health Authority and the Foundation emphasized the importance of collaboration. The Foundation’s primary mandate was to foster partnerships between health authorities. The commitment to work collectively was woven into the Canadian healthcare system. Thus, when the CEO wanted to collaborate, he found willing partners as well as resources to facilitate collective action.

The organization provides resources and helpful personnel to assist actions consistent with its values. In this way, values are enabling structures.[5] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Constrain Action

In the same way that organizations foster actions consistent with their values, they restrict people’s ability to act in ways inconsistent with those values. These constraints may take at least two forms: active opposition versus passive lack of support.[6]

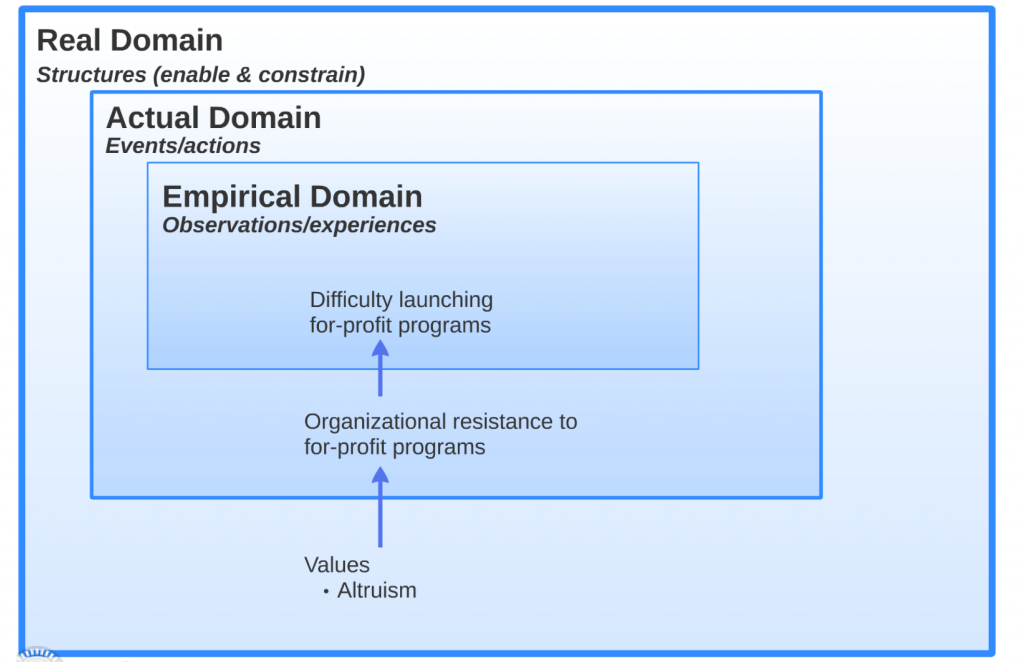

Values Lead to Active Opposition

The Canadian healthcare system deeply honors equal access to all Canadian citizens regardless of their financial wellbeing. The idea that the healthcare system would deny services because someone was unable to afford them is anathema to Canadian culture. This attitude speaks to the public sector value of altruism.

Imagine, then, if the CEO of the BC Health Authority choose to establish the Seniors Program as a for-profit division. The healthcare system’s stakeholders would actively resist such an attempt. The BC government, which funds health authorities, would put pressure on the CEO to stop. Citizens and patient groups would actively challenge the CEO’s attempts to offer for-profit services. The CEO would likely lose their job and be unable to work in the Canadian healthcare sector.

If you act in a manner inconsistent with the values of the organization, then the organization will work to stop you. If the values of the organization are ingrained deeply enough, then even the leader may lack the power to contradict them. In this way, values are constraining structures.[7] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Lead to a Passive Lack of Support

An organization need not actively resist an action to constrain it. Refusing to provide resources needed to perform an act can snuff it out as effectively. The members of the fellowship working on the Seniors Program faced this problem.

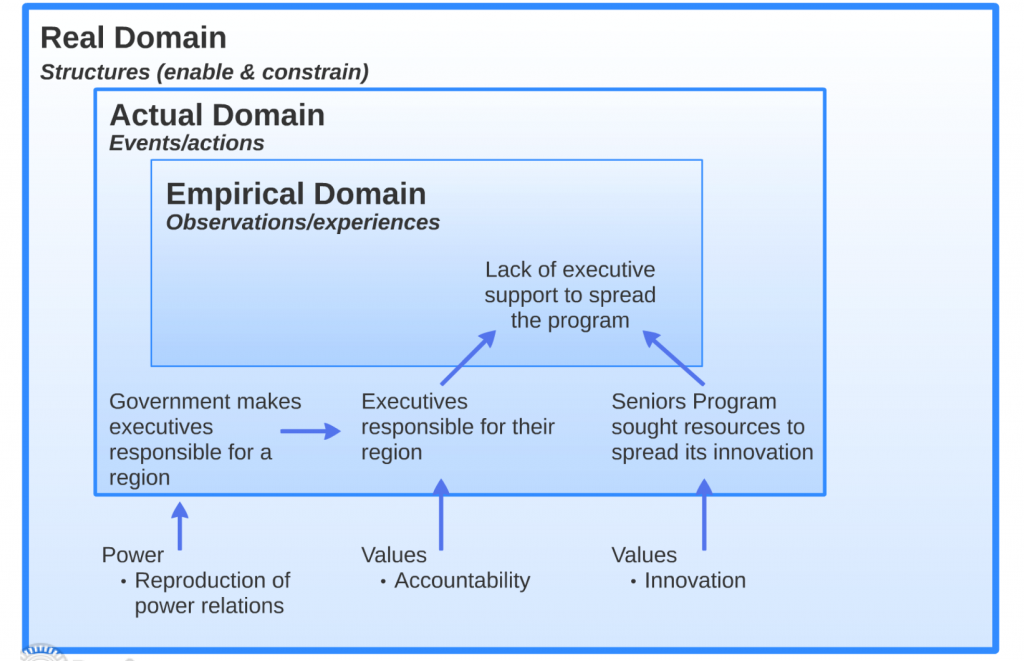

The original intent of the people starting the Seniors Program was to create an innovation that would spread across Canada. This desire was reinforced as the results of this study demonstrated their ability to reduce frailty. Yet, years after the completion of the study, the remaining members of the fellowship struggled to see their program adopted within their community. Spread outside of their community to the rest of Canada remained a distant dream. Why was this so?

Spreading innovation requires resources. You need personnel to sell the new idea. Other health regions need to be willing to take the risk of trying something new and suffering the disruption to the status quo as they integrate new activities. All of this costs time and money.

The provincial government provided funding to health authorities to administer healthcare inside their specific communities. Whereas the obligation for healthcare managers to use funding within their community was explicit, there was no mandate to use funds to spread innovations to other regions. Thus, managers believed using their funds to spread innovations to other communities was a breach of their responsibility. This belief speaks to the value of accountability. Though managers may see the Seniors Program’s importance, this sense of accountability constrained their ability to drive its wide-spread adoption. Starved of needed resources, attempts to spread the program floundered.

Even if an organization sees the desirability of action, its prevailing value system may constrain the ability of individuals to drive that action by denying them needed resources. In this way, values are constraining structures.[8] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Exercise: Can You Spot the Role of Power?

The above sections described how values enabled and constrained action. Review Chapter 6‘s discussion of power.

- Using Lukes’ four-dimension framework of power, identify which dimensions of power individuals and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

- Using Fleming & Spicer’s framework on the faces and sites of power, identify the different faces and sites of power individuals and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

- Using the tactics of power identified by Flyvbjerg, identify the different tactics of power that people and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

Key Takeaways

- Values enable by motivating action

- Values enable by providing access to resources needed to allow actions to happen

- Values constrain by creating active resistance

- Values constrain by creating passive lack of support

Acting to Overcome Constraining Structures

Recall from Chapter 3 that, though social structures enable and constrain action, it is our actions that produce and reproduce those structures. The healthcare system, for example, pursues the value of public interest because people created the system to implement that value. Once created, people within the organization exercise their power to enable actions consistent with this value while constraining those actions opposed.

Herein lies the potential for change, for people can exercise their power to enable different values. They may face resistance from the organization. They may fail. They can try, however, and sometimes, they succeed. Let’s continue looking at the case from Chapter 7 for an example.

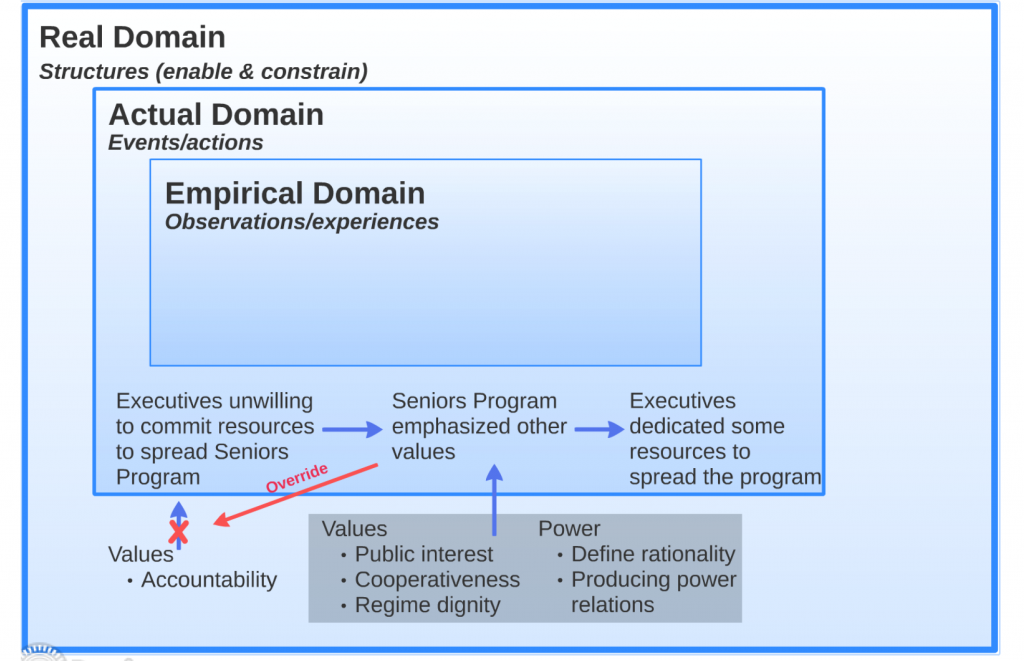

As described above, the value of accountability constrained managers’ willingness to use their resources to spread the Seniors Program to other communities. Had the fellowship stopped there, the program would have died. Despite this constraint on resourcing the program, different values in the organization did support its spread. The value of public interest drove healthcare workers, which the program delivered conclusively. Therefore, everyone wanted to see the program survive. The value of cooperativeness was present in the healthcare system, and so collaborating and working with other communities was supported. Plus, there was prestige to being a health authority that developed an innovation that the medical system adopted. Thus, there was some incentive to promote the spread of the program. This incentive speaks to the public sector value of regime dignity–the desire to look good.

The fellowship saw the importance of these other values to their organization and recognized their potential to enable the program’s spread. Thus, when seeking resources to support the spread of the Seniors Program, they emphasized its impact on the values of public interest, cooperativeness, and regime dignity. This approach successfully led some managers to support the program’s spread.

This is an example of defining rationality. They consequently received a bit of funding to continue spreading their innovation (an example of producing power relations).

The fellowship had keen insight into the different values active in their organization. Using that insight, they defined rationality to produce power relations that gave them access to the funding needed to spread the program. Though progress was much slower than the fellowship hoped, they still progressed nonetheless. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

This example highlights the relationship between values and power. The next section will explore that relationship further.

Exercise: Can You Spot the Role of Power?

The above example identified the power tactic of defining rationality and producing power relations that Chapter 6 introduced. Returning to Chapter 6:

- Identify which of Lukes’ four dimensions of power are present in the above example.

- Identify which of Fleming & Spicer’s faces and sites of power are present in the above example.

Key Takeaways

- By using tactics of power, such as producing power relations, defining rationality, and so on, individuals may overcome constraining structures

Values and Power

The previous section introduced the connection between values and power. Values may have guided what actions the organization enabled or constrained. It was through exercising power, however, that people enabled or constrained those actions. Let’s review several critical activities described above through the lens of power. Keep Chapter 6 handy as a reference.

The CEO formed a collaboration between BC and Nova Scotian health authorities along with the Foundation. This was an example of producing power relations. This collaboration gave each organization access to resources that they lacked on their own. Through this collaboration, the Seniors Program came into existence.

Though the CEO of the BC Health Authority supported the Seniors Program, the vice presidents of the organization initially opposed it due to their focus on reducing hospital overcrowding. Their opposition took the form of denying the fellowship resources of time and personnel. This was an example of power's second dimension. Rather than openly confront the CEO, vice presidents maintained stability by choosing, instead, to quietly starve the program of needed inputs.

When the fellowship tried to get the support of executive managers by presenting the Seniors Program as a solution to hospital overcrowding, this was an example of defining rationality. Additionally, the fellowship could have asked the CEO to coerce the vice presidents to support the program. Instead, they chose to use the tactic of defining rationality to avoid conflict. They relied on manipulation rather than coercion. They did this to maintain stability.

These are just a few examples. You may see others.

Generally, people seldom exercise power for the sake of it. Instead, they use power in pursuit of their values or to constrain the implementation of conflicting values. If values define the ends we find worth achieving, we exercise power to achieve those ends. If values define the appropriate means to achieve those ends, then values define which tactics of power are acceptable.

Key Takeaways

- It is people’s exercise of power that gives structures the force to enable or constrain actions

- Values guide the use of power

- People use power to pursue their values

- People use power to constrain the implementation of conflicting values

Values and power as social structures

Recall the ability of structures to enable or constrain action within a social setting. Values are a structure, as is power. In Chapter 3, we discussed that we might choose to act in a way that reinforces those structures or changes them. The more we understand the nature of the structures active in our organizations, the more we can act effectively. We can consciously choose which structures to reinforce and which ones to change. We can identify processes through which to change those structures and identify how the organization might support or resist our efforts.

The above chapter sought to deepen your understanding of the interplay between values and power. Values and power on their own, however, are insufficient for wise action. You also require rationality. In the same way that values and power are intertwined, so too are rationality and power. You will see in the next chapter that the relationship between rationality and power is rich and deep. Let’s now turn to explore this relationship.

In This Chapter, You Learned

How values enable and constrain action

- Values enable by motivating action

- Values enable by providing access to resources needed to allow actions to happen

- Values constrain by creating active resistance

- Values constrain by creating passive lack of support

How individuals may overcome the constraining nature of structures

- By using tactics of power, such as producing power relations, defining rationality, and so on, individuals may overcome constraining structures

How values and power interact

- It is people’s exercise of power that gives structures the force to enable or constrain actions

- Values guide the use of power

- People use power to pursue their values

- People use power to constrain the implementation of conflicting values

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Government of Canada. (2014, July 26). Canada Health Act: R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6. Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-6/page-1.html ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

Terminal values are those values pursued as ends in themselves.

A tactic of power where one party seeks to shape what others perceive as rational.

Two or more parties take action to form a working relationship with each other.

Obtaining what you want through suppressing conflict and limiting the scope of what is debated to issues you deem safe.

One party takes purposeful action to avoid conflict with another party.

Manipulation is a form of episodic power. It is the use of power to control the topics people discuss and to frame the issues discussed within desired boundaries.

Coercion is an form of episodic power. It is the use of power to compel another party's compliance when they otherwise would not comply.