Unit 29: Teamwork

Learning Objectives

After studying this unit, you will be able to

- define teamwork in professional settings

- compare and contrast positive and negative team roles and behaviours in the workplace

- discuss group strategies for solving problems

- demonstrate best practices in delivering constructive criticism and bad news in person

Introduction

Almost every posting for a job opening in a workplace location lists teamwork among the required skills. Why? Is it because every employer writing a job posting copies other job postings? No, it’s because every employer’s business success absolutely depends on people working well in teams to get the job done. A high-functioning, cohesive, and efficient team is essential to workplace productivity anywhere you have three or more people working together. Effective teamwork means working together toward a common goal guided by a common vision, and it’s a mighty force when firing on all cylinders. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has” (Sommers & Dineen, 1984, p. 158).

Compared with several people working independently, teams maximize productivity through collaborative problem solving. When each member brings a unique combination of skills, talents, experience, and education, their combined efforts make the team synergistic—i..e, more than the sum of its parts. Collaboration can motivate and result in creative solutions not possible in single-contractor projects. The range of views and diversity can energize the process, helping address creative blocks and stalemates. While the “work” part of “teamwork” may be engaging or even fun, it also requires effort and commitment to a production schedule that depends on the successful completion of individual and group responsibilities for the whole project to finish in a timely manner. Like a chain, the team is only as strong as its weakest member.

Teamwork is not without its challenges. The work itself may prove to be difficult as members juggle competing assignments and personal commitments. The work may also be compromised if team members are expected to conform and pressured to follow a plan, perform a procedure, or use a product that they themselves have not developed or don’t support. Groupthink, can also compromise the process and reduce efficiency. Personalities, competition, and internal conflict can factor into a team’s failure to produce, which is why care must be taken in how teams are assembled and managed.

John Thill and Courtland Bovee advocate for the following considerations when setting up a team:

- Select a responsible leader

- Promote cooperation

- Clarify goals

- Elicit commitment

- Clarify responsibilities

- Instill prompt action

- Apply technology

- Ensure technological compatibility

- Provide prompt feedback

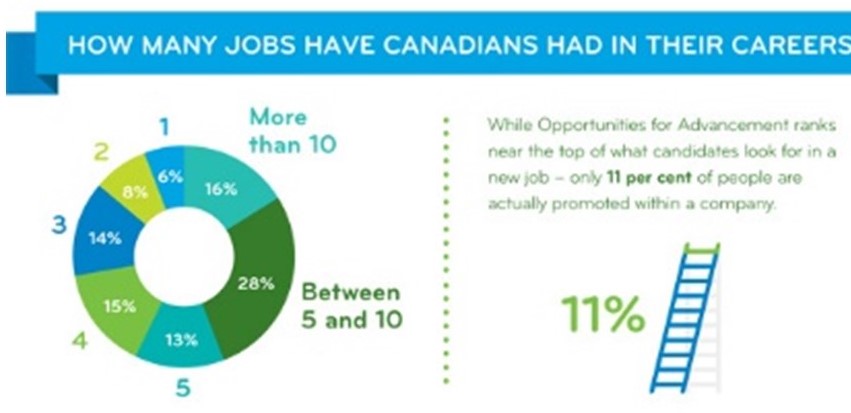

A Workopolis survey (see Figure 29. 1) revealed that 28% of Canadians expect to work at 5 – 10 different places of employment throughout their worklife, and 16% of Canadians expect to have more than 10 places of employment. In such an changing landscape, possessing good team and leadership skills is vital to your career success.

Group dynamics involve the interactions and processes of a team and influence the degree to which members feel a part of the goal and mission. A team with a strong identity can prove to be a powerful force. However, a team that exerts too much control over individual members runs the risk or reducing creative interactions, resulting in tunnel vision. A team that exerts too little control, neglecting all concern for process and areas of specific responsibility, may go nowhere. Striking a balance between motivation and encouragement is key to maximizing group productivity.

A skilled business communicator creates a positive team by first selecting members based on their areas of skill and expertise. Attention to each member’s style of communication also ensures the team’s smooth operation. If their talents are essential, introverts who prefer working alone may need additional encouragement to participate. Extroverts may need encouragement to listen to others and not dominate the conversation. Both are necessary, however, so the selecting for a diverse group of team members deserves serious consideration.

Developing Successful Teams

Phases of Team Development

Various types of teams typically go through four stages of development: Forming, storming, norming and performing. Let’s view this short video for an overview of each stage before a more in-depth review of each stage.

Forming: The first stage of team development is when individuals of a team first come together. Typically team members are polite with each other and attempt to get to know each other. Teams will discuss membership requirements, responsibilities, and size.

Storming: The second phase members will attempt to define roles and responsibilities. This stage is called storming because members may not yet know each others preferences and communication styles, consequently, misunderstanding and conflict are common in this stage.

Norming: The team begins to function as a team in the third phase of team development. Here, tension subsides, roles are clarified, and information is shared. A collective sense of purpose is formed and team members begin to work together to achieve their goals.

Performing: For teams that complete the first three phases of team development reach phase four. In phase four, teams have developed loyalty, respect and perhaps friendships. In this phase, teams establish routines and are able to be productive.

Positive and Negative Team Member Roles

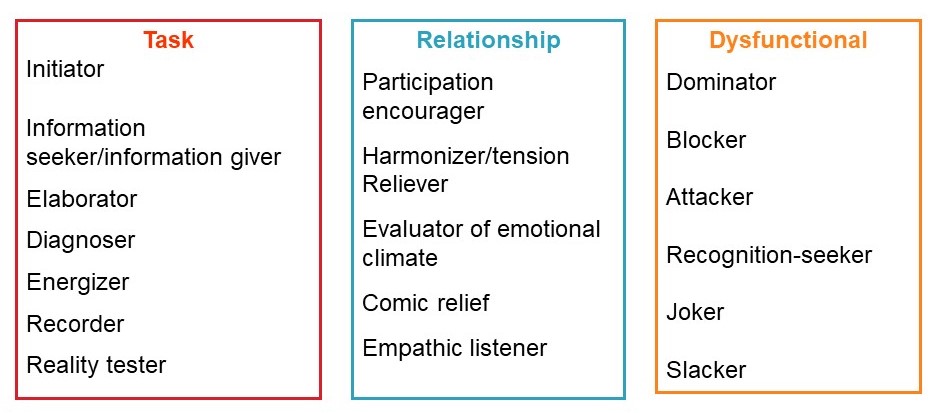

When a manager selects a team for a particular project, its success depends on its members filling various positive roles. There are a few standard roles that must be represented to achieve the team’s goals, but diversity is also key. Without an initiator-coordinator stepping up into a leadership position, for instance, the team will be a non-starter because team members such as the elaborator will just wait for more direction from the manager, who is busy with other things. If all the team members commit to filling a leadership role, however, the group will stall from the start with power struggles until the most dominant personality vanquishes the others, who will be bitterly unproductive relegated to a subordinate worker-bee role. A good manager must therefore be a good psychologist in building a team with diverse personality types and talents. Table 29.1 below captures some of these roles.

Table 29.1: Positive Group Roles

| Role | Actions |

| Initiator-coordinator | Suggests new ideas or new ways of looking at the problem |

| Elaborator | Builds on ideas and provides examples |

| Coordinator | Brings ideas, information, and suggestions together |

| Evaluator-critic | Evaluates ideas and provides constructive criticism |

| Recorder | Records ideas, examples, suggestions, and critiques |

| Comic relief | Uses humour to keep the team happy |

Of course, each team member here contributes work irrespective of their typical roles. The groupmate who always wanted to be recorder in high school because they thought that all they had to do what jot down some notes about what other people said and did, and otherwise contributed nothing, would be a liability as a slacker in a workplace team. We must therefore contrast the above roles with negative roles, some of which are captured in Table 29.2 below.

Table 29.2: Negative Group Roles

| Role | Actions |

| Dominator | Dominates discussion so others can’t take their turn |

| Recognition seeker | Seeks attention by relating discussion to their actions |

| Special-interest pleader | Relates discussion to special interests or personal agenda |

| Blocker | Blocks attempts at consensus consistently |

| Slacker | Does little-to-no work, forcing others to pick up the slack |

| Joker or clown | Seeks attention through humour and distracting members |

(Beene & Sheats, 1948; McLean, 2005)

Whether a team member has a positive or negative effect often depends on context. Just as the class clown can provide some much-needed comic relief when the timing’s right, they can also impede productivity when they merely distract members during work periods. An initiator-coordinator gets things started and provides direction, but a dominator will put down others’ ideas, belittle their contributions, and ultimately force people to contribute little and withdraw partially or altogether.(Business Communication for Success, 2015).

Perhaps the worst of all roles is the slacker. If you consider a game of tug-o-war between two teams of even strength, success depends on everyone on the team pulling as hard as they would if they were in a one-on-one match. The tendency of many, however, is to slack off a little, thinking that their contribution won’t be noticed and that everyone else on the team will make up for their lack of effort. The team’s work output will be much less than the sum of its parts, however, if everyone else thinks this, too. Preventing slacker tendencies requires clearly articulating in writing the expectations for everyone’s individual contributions. With such a contract to measure individual performance, each member can be held accountable for their work and take pride in their contribution to solving all the problems that the team overcame on its road to success.

Team Problem-solving

No matter who you are or where you live, problems are an inevitable part of life. This is true for groups as much as for individuals. Some work teams are formed specifically to solve problems. Other groups encounter problems for a wide variety of reasons. A problem might be important to the success of the operation, such as increasing sales or minimizing burnout, or it could be dysfunctional group dynamics such as some team members contributing more effort than others yet achieving worse results. Whatever the problem, having the resources of a group can be an advantage as different people can contribute different ideas for how to reach a satisfactory solution.

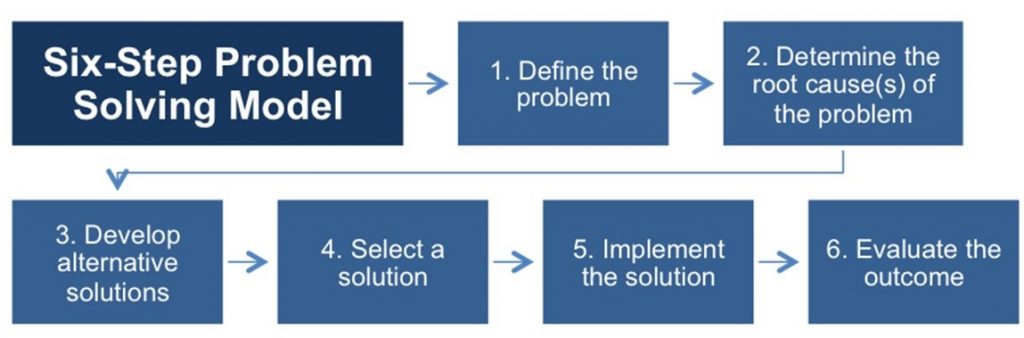

Once a group encounters a problem, questions that come up range from “Where do we start?” to “How do we solve it?” While there are many approaches to a problem, the American educational philosopher John Dewey’s reflective thinking sequence has stood the test of time. This seven-step process (Adler, 1996) produces positive results and serves as a handy organizational structure. If you are a member of a group that needs to solve a problem and don’t know where to start, consider these seven simple steps in a format adapted from Scott McLean (2005):

- Define the problem

- Analyze the problem

- Establish criteria for a successful resolution to the problem

- Consider possible solutions

- Decide on a solution or a select combination of solutions

- Implement the solution(s)

- Follow up on the solution(s)

Let’s discuss each step in detail.

Define the Problem: If you don’t know what the problem is, how do you know you can solve it? Defining the problem allows the group to set boundaries of what the problem is and what it isn’t, as well as to begin formalizing a description of the scope, size, or extent of the challenge the group will address. A problem that is too broadly defined can overwhelm the group and make getting started even more challenging. If the problem is too narrowly defined important considerations that, if addressed might will help to successfully resolve the problem, will fall outside of the scope and guarantee failure.

Analyze the Problem: The group must then analyzes the problem by figuring out its root causes so that the solution can address those rather than mere effects.

Establish Criteria: Establishing the criteria for a solution is the next step. At this point, information is coming in from diverse perspectives, and each group member has contributed information from their perspective, even though they may overlap at certain points.

Consider Possible Solutions to the Problem: The group listens to each other and now brainstorms ways to address the challenges they have analyzed while focusing resources on those solutions that are more likely to produce results.

Decide on a Solution: The may have a number of possible solutions. However, only one solution can be implemented. Thus, the group should complete a cost-benefit analysis, which ranks each solution according to its probable impact. Now that the options have been presented with their costs and benefits, deciding which courses of action are likely to yield the best outcomes is much easier.

Implement the Solution: Now that the group had determined the solution, implementation is the next step. To encourage a “buy-in” to the solution, ensure the team is involved in the implementation. Remain flexible and open to possible unforeseen problems that may arise during the implementation process.

Follow Up on the Solution: Have a follow-up meeting about the determined solution. Ensure to restate the solution and establish a feedback mechanism that will promote ongoing dialogue if necessary.

A problem may have several dimensions as well as solutions, but resources can be limited and not every solution is successful. Even learning what doesn’t work gives a team valuable intel and takes them one step closer to a solution. Altogether, the methodical approach serves as a useful guide through the problem-solving process that will eventually lead to success (Business Communication for Success, 2015).

Leading Teams

Teams depend on excellent leadership to guide it in the right direction and keep them on track. Without leadership, team members may act as if it’s an everyone-for-themselves game. It would be as if, instead of pulling in a straight line during a tug-o-war, everyone on your team pulled the rope in whatever direction suited them best, including opposite the direction you should be pulling. Good leadership gets everyone pulling in the same direction.

The further you go in your profession and the more you move up in terms of responsibility and pay scale, the more likely it is you’ll occupy a leadership role. This may be far from now or perhaps you have the drive, personality, and people-managing skills for such a role already. Either way, you must consider the leadership role you’ll occupy as one whose success depends largely on communication skills.

Paths to Leadership

Whether or not there are natural born leaders who come equipped with a combination of talents and traits that enable them to direct others has been the subject of debate since time immemorial. Today research in psychology tells us that someone with presence of mind, innate intelligence, and an engaging personality doesn’t necessarily destine them for a leadership role. The skill set that makes for an effective leader can be learned just like any other. On the other hand, some who think that they’re meant to be leaders lack the leadership skill set and manage only to do a great deal of damage whenever they’re trusted in such roles. History is full of examples of men who assumed leadership of vast empires merely by accident of birth and, through misgovernment, were responsible for the deaths of millions and met tragic ends themselves.

Leaders take on the role because they are appointed, elected, or emerge into the role through attrition (i.e., when others vacate it, leaving a vacuum that needs filling). Team members play an important role in this process. A democratic leader is elected or chosen by the group, but may also face serious challenges. If individual group members or constituent groups feel neglected or ignored, they may assert that the democratic leader doesn’t represent their interests after all. The democratic leader involves the group in the decision-making process, and ensures group ownership of the resulting decisions and actions as a result. This process is characterized by open and free discussions, and the democratic leader acknowledges this diversity of opinion.

An appointed leader, on the other hand, is designated by an authority to serve in that capacity irrespective of the thoughts or wishes of the group. This could go well or not. If the appointed leader is accepted, the team will function to achieve designated tasks. However, the work environment is likely to be a toxic if the appointment is based on cronyism or nepotism. Such a group will be pulling their tug-o-war rope in divergent directions until a more respected leader is appointed

An emergent leader is different from the first two paths by growing into the role often out of necessity. They may enter into the role merely because they know more than anyone around what needs to be done. The emergent leader is favoured in any true meritocracy—i.e., where skill, talent, and experience trump other considerations.

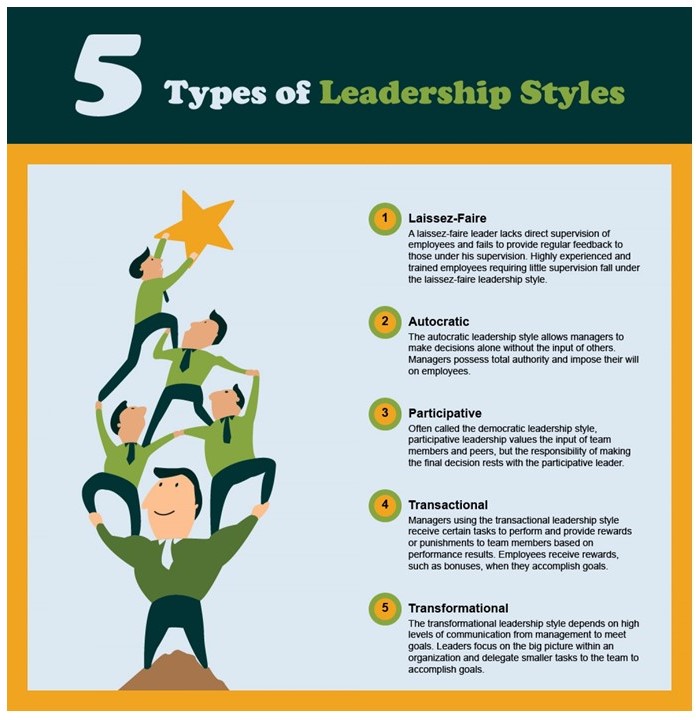

Leadership Style

We can see types of leaders in action and draw on common experience for examples. For good reason, the heart surgeon does not involve everyone democratically in the decision-making process during surgery, is typically appointed to the role through earned degrees and experience, and resembles a military sergeant more than a politician. The autocratic leader is self-directed and often establishes norms and rules of conduct for the group. Although this type of leadership can be advantageous in certain situations, it certainly doesn’t apply in most workplace situations.

Opposite the autocrat is the “live and let live” laissez-faire leader. In a professional setting, micromanaging employees is counter-productive. Employees know how to do their job, and have earned their role through time, effort, and experience. In such environments, A wise leader may choose to establish operating standards, overarching guidelines, and provide employees with the tools required to do their jobs.

We are not born leaders but may emerge into these roles if the context or environment requires our skill set. A transactional leader often occurs when someone has skills others do not. If you excel at all aspects of residential construction from having done those jobs yourself, your extensive knowledge and learned ability to coordinate other skilled labourers to complete the many sub-tasks that complete a project on time and on budget are prized and sought-after skills. Technical skills, from Internet technology to facilities maintenance, may experience moments where their particular area of knowledge is required to solve a problem. Their leadership will be in demand.

The participatory leader involves a central role of bringing people together for a common goal. This type of leader may set a vision, create benchmarks, and collaborate with a group. Whether it is a beautiful movement in music or a group of teams that comes together to address a common challenge, the participatory leader keeps the group on task as it moves towards its ultimate objective.

Coaches are often discussed in business-related books as models of leadership for good reason. A transformational leader combines many of the talents and skills we’ve discussed here, serving as a teacher, motivator, and keeper of the goals of the group. A coach may be autocratic at times, give pointed direction without input from the group, and stand on the sidelines while the players do what they’ve trained hard to do. The coach may look out for the group and defend it against bad calls, and may motivate players with words of encouragement. We can recognize some of the behaviours of coaches, but what specific traits have a positive influence on the group? Thomas Peters and Nancy Austin identify five important traits that produce results:

- Orientation and education

- Nurturing and encouragement

- Assessment and correction

- Listening and counselling

- Establishing group emphasis

Coaches are teachers, motivators, and keepers of the goals of the group. When team members forget that there is no “I” in the word “team,” coaches redirect the individuals’ attention and energy to the overall goals of the group. They conduct the group with a sense of timing and tempo, and at times, relax to let members demonstrate their talents. Through their listening skills and counselling, they come to know each member as an individual, but keep the team focus for all to see. They set an example. Coaches use more than one style of leadership and adapt to the context and environment. A skilled business communicator will recognize the merits of being an adaptable leader (Business Communication for Success, 2015).

Whatever the type of leader, much of their effectiveness comes down to how they communicate their expectations and direction. Some leaders manage by stick and others by carrot—i.e., some prefer to instill fear and command respect (whether earned or not) to get compliance by coercion, whereas others inspire employees to do their best work by a system of rewards including praise. The former usually leads to a toxic work environment where no one does their best work because the conditions are miserable. Someone who doesn’t look forward to going to work because of the psychological turmoil is not going to focus on accomplishing team goals. An employee who admires and gets along with both their manager and co-workers, on the other hand is productive employee motivated to doing good work in pursuit of even more praise and success.

Constructive Criticism

Performing work of a high quality is vital not only to your success in any profession but to the success of your team and company. How do you know if the quality of your work is meeting client, manager, co-worker, and other stakeholder expectations? Feedback. Whether this comes as a formal evaluation or informal comments, they’ll tell you whether you’re doing a great job, merely a good one, satisfactory, or a poor one that needs improving because their success depends on the quality of work you do. Poor leadership will merely point out what you’re doing wrong, which is negative feedback or mere criticism, and tell you to fix it without being much help. Good leadership may start with negative feedback and then tell you what you must do to improve. Inspiring leadership skips the negative criticism altogether and surrounds the constructive criticism with praise to effectively boost morale and motivate the worker to seek more praise.

Constructive criticism differs from mere negative criticism in that it is focused on improvement with clear, specific instructions for what exactly the receiver must do to meet expectations. If you merely wanted to criticize a report, for instance, you could say it’s terribly written and demand that it be fixed, leaving the writer to figure it out. Of course, if they don’t know what the expectations are, attempts at fixing it may result in yet more disappointment.

If you were offering constructive criticism, however, you would give the writer specific direction on how to improve. You might encourage them to revise and proofread it, perhaps taking advantage of MS Word’s spell checker and grammar checker, as well as perhaps some specific writing-guide review for recurring errors and the help of a second pair of eyes (see Ch. 5 on editing in the writing process). You may even offer to help yourself by going through a part of the report, pointing out how to fix certain errors, and thus guiding the writer to correct similar errors throughout.

Receiving Constructive Criticism

No one’s perfect, not even you, so your professional success depends on people telling you how to improve your performance. When you receive well-phrased constructive criticism, accept it in good faith as a gift because that’s what it is. If a close friend or colleague nicely tells you to pick out the broccoli between your teeth after lunching with them, they’re doing you the favour of telling you what you don’t know but need to in order to be successful or at least avoid failure. Your enemies, on the other hand, would say nothing, letting you go about your day embarrassing yourself in the hopes that it will contribute to your failure. Constructive criticism is an act of benevolence or mercy meant to improve not only your performance but also that of the team and company as a whole. Done well, constructive criticism is a quality assurance task rather than a personal attack. Be grateful and say thank you when someone is nice enough to look out for your best interests that way.

Receiving constructive criticism gracefully may mean stifling your defensive reflex. Important skills not only in the workplace but in basic communication include being a good listener and being able to take direction. Employees who can’t take direction well soon find themselves out of job because it puts them at odds with the goals of the team and company. Good listening means stifling the defensive reflex in your head before it gets out and has you rudely interrupting the speaker. Even if you begin mounting defenses in your head, you’re not effectively listening to the constructive criticism.

Receiving constructive criticism in a way that assures the speaker that you understand involves completing the communication process discussed in §1.3 above. You can indicate that you’re listening first with your nonverbals:

- Maintaining eye contact shows that you’re paying close attention to the speaker’s words and nonverbal inflections

- Nodding your head shows that you’re processing and understanding the information coming in, as well as agreeing

- Taking notes shows that you’re committing to the information by reviewing it later

Once you understand the constructive criticism, paraphrase it aloud to confirm your understanding. “So you’re basically saying that I should be doing X instead of Y, right?” If the speaker confirms your understanding, follow up by explaining how you’re going to implement the advice to assure them that their efforts in speaking to you won’t be in vain. Apologizing may even be necessary if you were clearly in the wrong.

Of course, if the constructive criticism isn’t so constructive—if it’s mere criticism, you would be right to ask for more help and specific direction. If the criticism is just plain wrong, perhaps because your manager is somehow biased or mistaken in thinking you’re at fault when really there are other culprits they are unaware of, respectfully correcting them is the right thing to do. You don’t want management to get the wrong impression about you in case that means you’ll be passed up for promotion down the road. When disagreeing, focus on the faulty points rather than on your feelings even if you’ve taken the feedback as a personal insult. Always maintain professionalism throughout such exchanges.

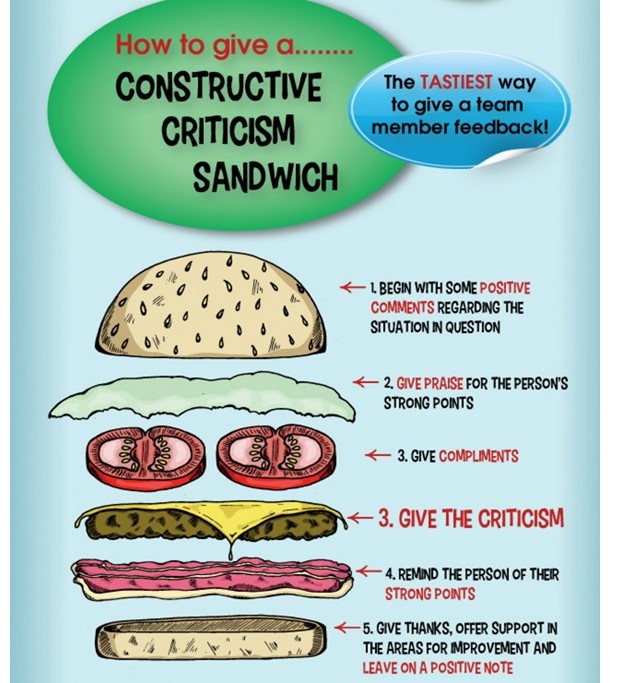

Giving “Hamburger Sandwich” Constructive Criticism

One of the most important functions of a supervisor or manager is to get the best work out of the people working under them. When those employees’ work leaves room for improvement, it’s the leader’s job to convince them that they can do better with a clear explanation of how. As we saw in unit 24 above, clarity and precision are necessary here because the quality of improvement will only be as good as the quality of instruction. As miscommunication, vague and misleading instruction will lead to little-to-no improvement or even more damage from people acting on misunderstandings caused by poor direction. Not only must the content of constructive criticism be of a high quality itself, but its packaging must be such that it properly motivates the receiver.

An effective way of delivering constructive criticism is called the “hamburger sandwich,” usually said with a more vulgar alternative to “hamburger.” Like sugar-coating bitter medicine, the idea here is to make the receiver feel good about themselves so that they’re in a receptive frame of mind for hearing, processing, and remembering the constructive criticism. If the constructive criticism (the hamburger) is focused on improvement and the receiver associates it with the praise that comes before and after (the slices of bread), the purely positive phrasing motivates them to actually improve. Like many other message types we’ve seen, this one’s organization divides into three parts as shown in Table 29.4 below.

Of course, this style of feedback may develop a bad reputation if done poorly, such as giving vague, weak praise (called “damning with faint praise”) when more specific, stronger praise is possible. If done well, however, the hamburger sandwich tends to make those receiving it feel good about themselves even as they’re motivate to do better.

Communicating Bad News

As the above video illustrates, not everyone is good at delivering bad news. The richness of the face-to-face channel makes it ideal for communicating bad news. As far as tasks go, however, few people enjoy either giving or receiving bad news this way. Since most people dislike conflict. Who enjoys making people sad or angry, making tears run down faces or provoking retaliatory confrontation? Besides being the right thing to do from an ethical standpoint, delivering negative news in person can be more effective than not and even necessary in many workplace situations.

Set a clear goal. Stephen Covey (1989) recommends beginning with the end in mind. Do you want your negative news to inform or bring about change? If so, what kind of change and to what degree? A clear conceptualization of the goal allows you to anticipate the possible responses, plan ahead, and get your emotional “house” in order.

Set the right tone. Your emotional response to the news and the audience, whether it’s one person or the whole company, will set the tone for the entire interaction. You may feel frustrated, angry, or hurt, but the display of these emotions is often more likely to make the problem worse than to help solve it.

Choose the right environment. If your response involves only one other person, a private, personal meeting is the best option, but it may be unavailable. People often work and contribute to projects from a distance via the internet and may only know each other via email, phone, or web conferencing (e.g., Skype). A personal meeting may be impractical or impossible. How then does one deliver negative news in person? By the best option available to both parties.

If you need to share the bad-news message with a larger audience, you may need to speak to a group or might even have to make a public presentation or speech. For high-profile bad news, for instance, a press conference enables a feedback loop with a question and answer session following the bad-news announcement. From meeting work colleagues in the hallway to a live, onstage audience under camera lights and a barrage of questions from reporters, the personal delivery of bad news is a challenging task that requires the richest channel (Business Communication for Success, 2015).

Key Takeaway

Almost all jobs require advanced teamwork skills, which involve being effective in performing a particular role (e.g., leader) in a working group, contributing to group problem-solving, and both giving and receiving constructive criticism.

Almost all jobs require advanced teamwork skills, which involve being effective in performing a particular role (e.g., leader) in a working group, contributing to group problem-solving, and both giving and receiving constructive criticism.

Exercises

1. Think of a group you belong to and identify some of the roles played by its members. Identify your role (give it a label, perhaps based on those given in this unit) and explain how it enriches the group.

1. Think of a group you belong to and identify some of the roles played by its members. Identify your role (give it a label, perhaps based on those given in this unit) and explain how it enriches the group.

2. Consider past group work you’ve done in high school or even recently in college and identify a particular problem you had to overcome to guarantee the group’s success. Did the group as a whole contribute to its solution, or did an individual member have to step up and pull through? Describe your problem-solving procedure. Was it successful immediately or did it require fine-tuning along the way?

3. Identify a problem that can only be solved with teamwork in the profession you’ll enter into upon graduating.

4. Think of a leader you admire and respect, someone who had or has authority over you. How did they become a leader? By appointment, democratic selection, or emergence? How would you characterize their leadership style? Are they autocratic, democratic or laissez-faire? Are they like a technician, conductor, or a coach?

5. Roleplay with a classmate the following scenario: You’re a mid-level manager and are concerned about an employee arriving 15-20 minutes late every day, although sometimes it’s around 30-40 minutes. The employee leaves at the same time as everyone else at the end of the day, so that missing work time isn’t made up. What you don’t know (but will find out from talking with the employee) is that they must drop their child off at elementary school shortly before 8 a.m., battle gridlock highway traffic on the way to work (hence the lateness), then leave at a certain time to pick their child up from after-school daycare (hence not being able to stay later). What you do know is that talking with the employee in private is the right way to handle this and that the executive director above you considers it your responsibility to have everyone arriving on time and being paid for their hours as stipulated in their contracts; the director isn’t afraid of firing someone for such a breach of contract, so you have the authority to present the employee with that consequence if you feel that it’s necessary. The fact that this employee is being paid for working fewer hours than stipulated in the contract will be a strike against you unless you either get them back on track or fire them if you can’t work their full hours. Be creative in discussing an amicable solution with the employee that satisfies everyone involved. Switch between being both the manager and the employee in your roleplay.

References

Adler, R. (1996). Communicating at work: Principles and practices for business and the professions. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Beene, K., & Sheats, P. (1948). Functional roles of group members. Journal of Social Issues, 37, 41–49.

Clker-Free-Vector-Images / 29597 Images. (2012, April 14). Cheeseburger meat bun cheese 34315. Retrieved from https://pixabay.com/en/cheeseburger-meat-bun-cheese-34315/

Covey, S. (1989). The seven habits of highly effective people. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Frank G. Sommers & Tana Dineen. (1984). Curing nuclear madness: A new-age prescription for personal action. Toronto: Methuen. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books/about/Curing_Nuclear_Madness.html?id=0d0OAAAAQAAJ&redir_esc=y

Free Management Books. (n.d.). The six step problem solving model. News. Retrieved from http://www.free-management-ebooks.com/news/six-step-problem-solving-model/

Gray, D. (2011, November 27). Carrot-and-stick management. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/davegray/6416285269/

Harris, T., & Sherblom, J. (1999). Small group and team communication. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Peters, T., & Austin, N. (1985). A passion for excellence: The leadership difference. New York: Random House.

Seiter, C. (2020). How to give and receive feedback at work: The psychology of criticism. Buffer Inc. Retrieved from https://open.buffer.com/how-to-give-receive-feedback-work/

Thill, J. V., & Bovee, C. L. (2002). Essentials of business communication. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Visual.ly. (n.d.). 5 types of leadership styles. Retrieved from https://visual.ly/community/Infographics/business/types-leadership-styles-essential-guide

VitalSmarts Video. (2017). How to deliver bad news at work [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6pRXVbhlJk

Workforce Singapore. (2013). Learn how to manage people and be a better leader [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PWmhl6rzVpM

the tendency to accept the group’s ideas and actions in spite of individual concerns

The appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications.

The practice among those with power or influence of favoring relatives or friends, especially by giving them jobs.

A system in which power is vested in individual people on the basis of talent, effort, and achievement, rather than wealth, connections or social class.