5 Persuasion and Attitude Change

Every day we are bombarded by advertisements of every sort. The goal of these ads is to sell us cars, computers, video games, clothes, and even political candidates. The ads appear on billboards, website popup ads, buses, TV infomercials, and…well, you name it! It’s been estimated that over $500 billion is spent annually on advertising worldwide (Johnson, 2013).

There is substantial evidence that advertising is effective in changing attitudes. After the R. J. Reynolds Company started airing its Joe Camel ads for cigarettes on TV in the 1980s, Camel’s share of cigarette sales to children increased dramatically. But persuasion can also have more positive outcomes. For instance, a review of the research literature indicates that mass-media anti-smoking campaigns are associated with reduced smoking rates among both adults and youth (Friend & Levy, 2001). Persuasion is also used to encourage people to donate to charitable causes, to volunteer to give blood, and to engage in healthy behaviors.

Persuasion

Persuasion has been defined as “the process by which a message induces change in beliefs, attitudes, or behaviours” (Myers, 2011). Persuasion can take many forms. It may, for example, differ in whether it targets public compliance or private acceptance, is short-term or long-term, whether it involves slowly escalating commitments or sudden interventions and, most of all, in the benevolence of its intentions. When persuasion is well-meaning, we might call it education. When it is manipulative, it might be called mind control (Levine, 2003).

Marketing Context: The Effective Use of Persuasion by Apple to Drive Sales

On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs, the enigmatic co-founder and CEO of Apple, Inc., introduced the first iPhone to the world. The device quickly revolutionized the smartphone industry and changed what consumers came to expect from their phones. In the years since, smartphones have changed from being regarded as status symbols (Apple sold close to 1.4 million iPhones during their first year on the market) to fairly commonplace and essential tools. One out of every five people in the world now owns a smartphone, there are more smartphones in use in the world than PCs, and it is difficult for many young people to imagine how anyone ever managed to function without them. If you consider the relatively high cost of these devices, this transformation has been truly remarkable.

Much of this shift in attitude can be credited to the impressive use of tactics of persuasion employed by smartphone manufacturers like Apple and Samsung. The typical marketing campaign for a new model of an iPhone delivers a carefully crafted message that cleverly weaves together stories, visuals, and music to create an emotional experience for the viewing public. These messages are often designed to showcase the range of uses of the device and to evoke a sense of need. Apple also strives to form relationships with its customers, something that is illustrated by the fact that 86 per cent of those who purchased the iPhone 5S were upgrading from a previous model. This strategy has benefited Apple tremendously as it has sold over 400 million iPhones since 2007, making it one of the wealthiest companies in the world.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

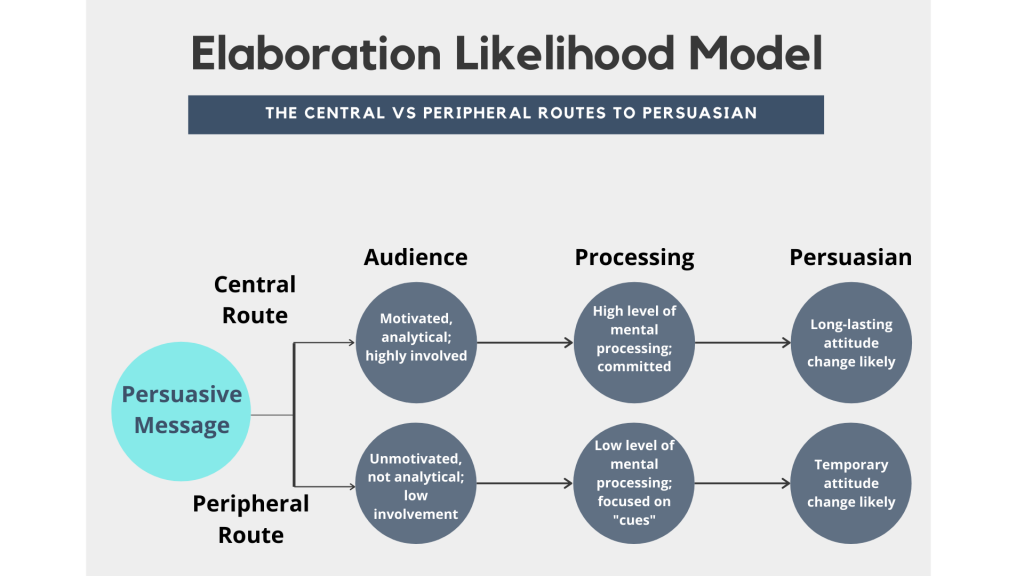

An especially popular model that describes the dynamics of persuasion is the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The elaboration likelihood model considers the variables of the attitude change approach — that is, features of the source of the persuasive message, contents of the message, and characteristics of the audience are used to determine when attitude change will occur. According to the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion, there are two main routes that play a role in delivering a persuasive message: central and peripheral (see image below).

The central route is logic driven and uses data and facts to convince people of an argument’s worthiness. For example, a car company seeking to persuade you to purchase their model will emphasize the car’s safety features and fuel economy. This is a direct route to persuasion that focuses on the quality of the information. In order for the central route of persuasion to be effective in changing attitudes, thoughts, and behaviours, the argument must be strong and, if successful, will result in lasting attitude change.

The central route to persuasion works best when the target of persuasion, or the audience, is analytical and willing to engage in processing of the information. From an advertiser’s perspective, what products would be best sold using the central route to persuasion? What audience would most likely be influenced to buy the product? One example is buying a computer. It is likely, for example, that small business owners might be especially influenced by the focus on the computer’s quality and features such as processing speed and memory capacity.

The peripheral route is an indirect route that uses peripheral cues to associate positivity with the message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Instead of focusing on the facts and a product’s quality, the peripheral route relies on association with positive characteristics such as positive emotions and celebrity endorsement. For example, having a popular athlete advertise athletic shoes is a common method used to encourage young adults to purchase the shoes. This route to attitude change does not require much effort or information processing. This method of persuasion may promote positivity toward the message or product, but it typically results in less permanent attitude or behaviour change. The audience does not need to be analytical or motivated to process the message. In fact, a peripheral route to persuasion may not even be noticed by the audience, for example in the strategy of product placement. Product placement refers to putting a product with a clear brand name or brand identity in a TV show or movie to promote the product (Gupta & Lord, 1998). For example, one season of the reality series American Idol prominently showed the panel of judges drinking out of cups that displayed the Coca-Cola logo. What other products would be best sold using the peripheral route to persuasion? Another example is clothing: A retailer may focus on celebrities that are wearing the same style of clothing.

Student Op-Ed: How to be a Woman (according to the Susan G. Komen Foundation)

The peripheral route to persuasion, a function of the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion, is a consumer behaviour concept that can explain how the Susan G. Komen Foundation (“Komen”) and the Avon Foundation for Women (“Avon”) attracted attention without providing much factual information on their goal: curing breast cancer. The peripheral route to persuasion is the cognitive path that consumers take when they rely on extraneous information that is not the actual message, such as the source of the message, the package it comes in, etc. to make a decision about how they feel about that product (Solomon, White & Dahl, 2014). These marketing tactics are designed for low-involvement processing, wherein a consumer doesn’t think very much about a buying decision before making a purchase. The extraneous information, or peripheral cues, in the case of the Pink Ribbon Movement is based almost exclusively on hyperfemininity and is made to evoke strong emotions of hope and fulfillment.

In the film Pink Ribbons, Inc. (Pool, 2011), we follow Komen, a nonprofit dedicated to finding a cure for breast cancer, watching how they raise awareness for their cause. Celebrity endorsements are a popular method, using stars like Halle Berry and Christie Brinkley to promote their events. And because Komen, as depicted in the film, doesn’t have a lot of information on how they’re actually going to cure breast cancer, they capture their audience with the attractiveness of the information source and not the information itself. These celebrities, or “sources”, fit the archetype of what the “ideal” woman should look like, and very specifically they fit the role of what a “healthy” woman should look like. And so the Komen uses their star power to not only garner attention but also promote a look that follows the brand that they’ve built.

Looking at Avon, a nonprofit run by the cosmetics company Avon Products, Inc., we see the same trend of using low-involvement processing. Avon uses this curated culture of “sisterhood” to promote their products, relying on the fact that their audience will feel that pressure to show their care for other women and then make the connection that supporting women means supporting the use of cosmetics. They immerse their message within the context that being pretty is related to being healthy. While this has nothing to do with finding a cure for breast cancer, it does the job of persuading the consumer to think less and act more by creating a connection that is simple and convenient.

The peripheral route is the path we take when we aren’t invested in learning more about a product or service we seek to purchase. I think the popularity of the Pink Ribbon Movement is brought on through specific marketing that relies on the fact that, as a culture, we are obsessed with women’s bodies. But we know so little about them that there’s a limit to how we can help ourselves and other women stay healthy. I don’t think indifference is the driving factor when it comes to these low-involvement purchasing situations, as much as ignorance is.

I care about finding more information about breast cancer, but I don’t know where to put that energy because information is genuinely hard to find. Komen and Avon provided a place for us to put our anxiety and our grief, provided we buy into the shiny, pink package they deliver to us. With public health issues, the messages should be informational, educational, and should require a high degree of mental processing; but instead The Pink Ribbon Movement hands us an easy-to-read instruction manual that is too convenient to resist.

The Source of Persuasion: The Triad of Trustworthiness

Effective persuasion requires trusting the source of the communication. Studies have identified three characteristics that lead to trust: perceived authority, honesty, and likability.

- Honesty: Honesty is the moral dimension of trustworthiness. Persuasion professionals have long understood how critical it is to their efforts. Marketers, for example, dedicate exorbitant resources to developing and maintaining an image of honesty. A trusted brand or company name becomes a mental shortcut for consumers. It is estimated that some 50,000 new products come out each year. Forrester Research, a marketing research company, calculates that children have seen almost six million ads by the age of 16. An established brand name helps us cut through this volume of information. It signals we are in safe territory. “The real suggestion to convey,” advertising leader Theodore MacManus observed in 1910, “is that the man manufacturing the product is an honest man, and the product is an honest product, to be preferred above all others” (Fox, 1997).

- Likability: People tend to favour products that are associated with people they like. This is the key ingredient to celebrity endorsements. While there are a lot of factors that can contribute to likability, being physically attractive is one of the most influential. If we know that celebrities aren’t really experts, and that they are being paid to say what they’re saying, why do their endorsements sell so many products? Ultimately, it is because we like them. More than any single quality, we trust people we like. The mix of qualities that make a person likable are complex and often do not generalize from one situation to another. One clear finding, however, is that physically attractive people tend to be liked more. In fact, we prefer them to a disturbing extent: Various studies have shown we perceive attractive people as smarter, kinder, stronger, more successful, more socially skilled, better poised, better adjusted, more exciting, more nurturing, and, most important, of higher moral character. All of this is based on no other information than their physical appearance (e.g., Dion, Berscheid & Walster, 1972).

When the source appears to have any or all of these characteristics, people not only are more willing to agree to their request but are willing to do so without carefully considering the facts. We assume we are on safe ground and are happy to shortcut the tedious process of informed decision making. As a result, we are more susceptible to messages and requests, no matter their particular content or how peripheral they may be.

Source Credibility

Source credibility means that consumers perceive the source (or spokesperson) as an expert who is objective and trustworthy (“I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV”). A credible source will provide information on competing products, not just one product, to help the consumer make a more informed choice. We also see the impact of credibility in Web sites like eBay or Wikipedia and numerous blogs, where readers rate the quality of others’ submissions to enable the entire audience to judge whose posts are worth reading.

Source Attractiveness

Source attractiveness refers to the source’s perceived social value, not just his or her physical appearance. High social value comes partly from physical attractiveness but also from personality, social status, or similarity to the receiver. We like to listen to people who are like us, which is why “typical” consumers are effective when they endorse everyday products. So, when we think about source attractiveness, it’s important to keep in mind that “attractiveness” is not just physical beauty. The advertising that is most effective isn’t necessarily the one that pairs a Hollywood idol with a product. Indeed, one study found that many students were more convinced by an endorsement from a fictional fellow student than from a celebrity. As a researcher explained, “They [students] like to make sure their product is fashionable and trendy among people who resemble them, rather than approved by celebrities like David Beckham, Brad Pitt or Scarlett Johansson. So they are more influenced by an endorsement from an ordinary person like them” (“Celebrity Ads…”, 2007).

Still, all things equal, there’s a lot of evidence that physically attractive people are more persuasive. Our culture (like many others) has a bias toward good-looking people that teaches they are more likely to possess other desirable traits as well. Researchers call this the “what is beautiful is good” hypothesis (Dion et al., 1972).

Match-Up Hypothesis

For celebrity campaigns to be effective, the endorser must have a clear and popular image. In addition, the celebrity’s image and that of the product they endorse should be similar — researchers refer to this as the match-up hypothesis (Kamins, 1990; Basil, 1994). A market research company developed one widely used measure called the Q-score (Q stands for quality) to decide if a celebrity will make a good endorser. The score includes level of familiarity with a name and the number of respondents who indicate that a person, program, or character is a favorite (Kahle & Kahle, 2005).

A good match-up is crucial; fame alone is not enough. The celebrity may bring the brand visibility, but that visibility can be overshadowed by controversy that the spokesperson can generate. For example, in 2018, Gal Gadot became a brand ambassador for Huawei and tweeted a promotional video for the brand’s Android cell phone. However, Gal uploaded the video using “Twitter for iPhone,” a competing product for Huawei (Ellevsen, 2018). This raised controversy and social buzz that cloaked the purpose of the promotional video; to garner attention for the brand. Similarly, the Beef Board faced negative publicity when its spokesperson, Cybill Shepherd, admitted she did not like to eat beef. Without question, it helps when your spokesperson actually uses (or matches up with) the product they are promoting. In the case of Lance Armstrong, sportswear giant Nike, cycle maker Trek, and Budweiser brewer Anheuser-Busch ended their sponsorships with the cyclist after his admittance of using unethical performance enhancing means to win (Meyer, 2019).

Because consumers tend to view the brand through the lens of its spokesperson, an advertiser can’t choose an endorser just based on a whim (or the person’s good looks). Consider Tupperware, which decided to mount an advertising campaign to support its traditional word-of-mouth and Tupperware party promotional strategies. The brand is 60 years old and harkens back to 1950s-style June Cleaver moms (A “Leave it to Beaver” reference that dates too far back for most readers). In its attempt to stay relevant and up-to-date, the company looked for a modern image of the working mom. Rather than going with a spokesperson like Martha Stewart, who would reinforce the old image of Tupperware, the company chose Brooke Shields as their spokesperson. “We’ve seen her go from a model to an actress to a Princeton graduate…then be open with issues she’s had with depression,” said Tupperware Chairman-CEO Rick Goings. That, he said, meshed perfectly with the company’s new “Chain of Confidence” campaign, which is dedicated to building the self-esteem of women and girls (Neff, 2007).

Celebrity Endorsements

Celebrity endorsements are a frequent feature in commercials aimed at children. The practice has aroused considerable ethical concern, and research shows the concern is warranted. In a study funded by the Federal Trade Commission, more than 400 children ages 8 to 14 were shown one of various commercials for a model racing set. Some of the commercials featured an endorsement from a famous race car driver, some included real racing footage, and others included neither. Children who watched the celebrity endorser not only preferred the toy cars more but were convinced the endorser was an expert about the toys. This held true for children of all ages. In addition, they believed the toy race cars were bigger, faster, and more complex than real race cars they saw on film. They were also less likely to believe the commercial was staged (Ross et al., 1984).

Star Power & the Halo Effect

Star Power

Star power can best be explained like this: if a famous person believes a product is good, you can believe it, too. For the advertising to be effective, however, the connection between the product and the celebrity should be clear. When Louis Vuitton featured Mikhail Gorbachev in an ad in Vogue, the tie was not clear. Why would the association with the former Soviet leader who brought an end to Communism motivate a consumer to buy a luxury brand bag?

This framework is effective because celebrities embody cultural meanings — they symbolize important categories such as status and social class (a “working-class hero,” such as Peter Griffin on Family Guy), gender (a “tough woman,” such as Nancy on Weeds), or personality types (the nerdy but earnest Hiro on Heroes). Ideally, the advertiser decides what meanings the product should convey (that is, how it should position the item in the marketplace) and then chooses a celebrity who embodies a similar meaning. The product’s meaning thus moves from the manufacturer to the consumer, using the star as a vehicle.

The Halo Effect

Armed with positive information about a person we then tend to assume other positive qualities, called the halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). So if a person is really nice, we will also assume they are attractive or intelligent. If rude, we will see them as unintelligent or unattractive. The halo effect creates a type of cognitive bias and marketers know this! If we have a favourable attitude towards a brand’s products, there’s a good chance that same attitude will be extended to the brand’s other products, or even future product-line extensions. The same can be said about a celebrity endorser: if we have a favourable attitude towards a particular celebrity or athlete and they endorse a product, there’s a good chance we will also have a favourable attitude towards the product they are endorsing.

The Balance Theory of Attitudes

Balance Theory is a conceptual framework that demonstrates how consistency as a motivational force predicts attitude change and behaviour. The model can be used to predict the behaviour of consumers in situations where a celebrity endorser may be involved. If the audience (consumers) have a favourable attitude towards a celebrity and perceive that the celebrity likes a particular brand (communicated through an endorsement deal), the consumer is more likely to develop a positive attitude towards the brand – thus providing “balance” between all three components in the triad (the consumer, the celebrity, and the brand). However, imbalance can occur if a consumer develops a dislike towards the celebrity (e.g. due to scandal), which could then result in the same negative attitude being extended to the brand if they continue to maintain positive ties with the celebrity. Many brands will “drop” a celebrity in order to maintain a positive relationship with consumers.

The Balance Theory of Attitudes can be explained visually and mathematically:

The Balance Theory Explained

Barely a day goes by without a story in the news that features a brand or corporation who has decided to cut ties with a celebrity, an athlete, and even a politician. At the time of writing, American democracy is being put to the test and finding itself challenged by fascists and domestic terrorists. On January 6, 2021, the United States Congress experienced an attack by violent insurgents who attempted, what many believe to have been, a coup or at the very least, a serious disruption to the democratic process involving the peaceful transition of power and government from President Donald Trump to President-Elect Joe Biden.

In the following week, many corporations suspended, recalled, or halted funding to those politicians who made attempts to disrupt the transition of government. New York Times writers Andrew Ross Sorkin, Jason Karaian, Michael J. de la Merced, Lauren Hirsch, and Ephrat Livni, documented and summarized those companies who are “rethinking” their political donations (2021). Among the most notable corporations who paused all political donations were Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, and Citigroup. Those corporations who paused donations to specific politicians (individuals who voted against certification of the election) included Marriott and Blue Cross Blue Shield.

The discussion below serves to highlight how the Balance Theory works in a retail branding context: however, this framework can be applied to the discussion above as well. Students are encouraged to come up with their own examples of the Balance Theory in action!

Warning! Doing Business with Trump Could Hurt Your Bottom Line

A consumer behaviour concept, known as “The Balance Theory of Attitudes”, can predict why so many brands are “dumping Trump” to save their businesses. Since the 2016 election of US President Donald Trump, many consumer-based activism movements emerged to voice their disapproval of the Republican president who has mocked the disabled; called for an illegal “Muslim ban”; threatened to criminalize abortion; accused Mexicans of being violent criminals; encouraged harm and brutality towards Black Americans; and, perpetuated conspiracy theories about “fake news”.

According to Solomon et al (7th ed), the Balance Theory of Attitudes is a model that involves a triad that considers the relationship between 3 entities: (1) a person and their perception of an (2) attitude object, and some other person or object (Solomon, 2017). It matters less if perceptions and attitudes among the individuals and objects are negative or positive and more if they are in balance.

When the triad is imbalanced due to an attitude change (e.g. by consumers), there will be a natural draw to remove cognitive dissonance and restore balance by changing the nature of one other relationship within the triad. This is how the model can be used to predict brand success or brand disassociation.

After the 2016 Presidential election, an online movement known as #GrabYourWallet started exposing those brands who were continuing to choose to do business with Trump (grabyourwallet.org, 2017). For example, Nordstrom (a popular US department store), Ivanka Trump (daughter to Donald Trump who sells women’s merchandise), and a fictitious loyal consumer (let’s call her “Jennifer”) demonstrate how the Balance Theory predicts outcomes when attitude change occurs.

Before the election, this triad (Nordstrom, Ivanka, Jennifer) all existed in a positive and balanced relationship. Jennifer, an ideal consumer in Nordstrom’s perspective, had a favourable attitude towards Ivanka Trump which encouraged the department store to carry the Trump branded merchandise in its stores.

Shortly after the election, however, Jennifer’s attitude began to change. The violent rhetoric and lies made by the US President met with her disapproval and she became increasingly concerned about the growing hostilities towards BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour). Jennifer reflected on how her behaviour as a consumer made her complicit (passively supportive) of the President and his family: her once favourable attitude towards Ivanka and the Trump clothing line now turned sour. Negative. With this change, the triad found itself imbalanced and Nordstrom was faced with a big decision: continue to carry Ivanka Trump merchandise and risk losing loyal consumers like Jennifer, or, dump Trump and maintain a positive relationship with its consumers. What was the best course of action for Nordstrom in this situation? Knowing that Jennifer represented a majority of its consumer-base, Nordstrom had to protect its bottom line and brand reputation.

So, the Balance Theory of Attitudes reveals to us that the only real option Nordstrom had was to drop Ivanka Trump’s merchandise from its retail mix. (Which is exactly what the mega retailer did.) They weighed the cost of doing business with Trump versus the long-term value loyal consumers bring to their bottom line and chose to maintain a positive and favourable relationship with Jennifer and convert its once positive support for Ivanka Trump into a negative one. And voilà, balance restored.

As a consumer I am aware that I am responsible for the purchase decisions I make and the impact those decisions have on business, society, and the people I may influence around me (my husband, my kids, my students). Given that female consumers make up 50% of our consumer economy and are responsible for 80% of household purchasing decisions, I recognize that I hold a lot of power. It has taken time, but I have evolved to become a much more conscientious consumer: I recognize that my consumer decision making reflects the kind of person I wish to be — one who values social justice, equality, sustainability, and equity.

When a brand stands in direct opposition to consumers’ values, the Balance Theory of Attitudes will often predict the outcome.

Creatively Persuasive

Beyond endorsements and the use of a source, persuasion can take on other forms and techniques as well. The following list provides an overview of different ways in which persuasion is designed to communicate compatibility, necessity, and urgency to consumers.

1. Reciprocity

“There is no duty more indispensable than that of returning a kindness,” wrote Cicero. Humans are motivated by a sense of equity and fairness. When someone does something for us or gives us something, we feel obligated to return the favor in kind. It triggers one of the most powerful of social norms, the reciprocity rule, whereby we feel compelled to repay, in equitable value, what another person has given to us.

Gouldner (1960), in his seminal study of the reciprocity rule, found it appears in every culture. It lays the basis for virtually every type of social relationship, from the legalities of business arrangements to the subtle exchanges within a romance. A salesperson may offer free gifts, concessions, or their valuable time in order to get us to do something for them in return. For example, if a colleague helps you when you’re busy with a project, you might feel obliged to support her ideas for improving team processes. You might decide to buy more from a supplier if they have offered you an aggressive discount. Or, you might give money to a charity fundraiser who has given you a flower in the street (Cialdini, 2008; Levine, 2003).

2. Social Proof

If everyone is doing it, it must be right. People are more likely to work late if others on their team are doing the same, to put a tip in a jar that already contains money, or eat in a restaurant that is busy. This principle derives from two extremely powerful social forces — social comparison and conformity. We compare our behaviour to what others are doing and, if there is a discrepancy between the other person and ourselves, we feel pressure to change (Cialdini, 2008).

The principle of social proof is so common that it easily passes unnoticed. Advertisements, for example, often consist of little more than attractive social models appealing to our desire to be one of the group. For example, the German candy company Haribo suggests that when you purchase their products you are joining a larger society of satisfied customers: “Kids and grown-ups love it so– the happy world of Haribo”. Sometimes social cues are presented with such specificity that it is as if the target is being manipulated by a puppeteer — for example, the laugh tracks on situation comedies that instruct one not only when to laugh but how to laugh. Studies find these techniques work. Fuller and Skeehy-Skeffington (1974), found that audiences laughed longer and more when a laugh track accompanied the show than when it did not, even though respondents knew the laughs they heard were connived by a technician from old tapes that had nothing to do with the show they were watching. People are particularly susceptible to social proof (a) when they are feeling uncertain, and (b) if the people in the comparison group seem to be similar to ourselves. As P.T. Barnum once said, “Nothing draws a crowd like a crowd.”

3. Commitment & Consistency

Westerners have a desire to both feel and be perceived to act consistently. Once we have made an initial commitment, it is more likely that we will agree to subsequent commitments that follow from the first. Knowing this, a clever persuasion artist might induce someone to agree to a difficult-to-refuse small request and follow this with progressively larger requests that were his target from the beginning. The process is known as getting a foot in the door and then slowly escalating the commitments.

Paradoxically, we are less likely to say “No” to a large request than we are to a small request when it follows this pattern. This can have costly consequences. Levine (2003), for example, found ex-cult members tend to agree with the statement: “Nobody ever joins a cult. They just postpone the decision to leave.”

4. A Door in the Face

Some techniques bring a paradoxical approach to the escalation sequence by pushing a request to or beyond its acceptable limit and then backing off. In the door-in-the-face (sometimes called the reject-then-compromise) procedure, the persuader begins with a large request they expect will be rejected. They want the door to be slammed in their face. Looking forlorn, they now follow this with a smaller request, which, unknown to the customer, was their target all along.

In one study, for example, Mowen and Cialdini (1980), posing as representatives of the fictitious “California Mutual Insurance Co.,” asked university students walking on campus if they’d be willing to fill out a survey about safety in the home or dorm. The survey, students were told, would take about 15 minutes. Not surprisingly, most of the students declined — only one out of four complied with the request. In another condition, however, the researchers door-in-the-faced them by beginning with a much larger request. “The survey takes about two hours,” students were told. Then, after the subject declined to participate, the experimenters retreated to the target request: “. . . look, one part of the survey is particularly important and is fairly short. It will take only 15 minutes to administer.” Almost twice as many now complied.

5. “And That’s Not All!”

The that’s-not-all technique also begins with the salesperson asking a high price. This is followed by several seconds’ pause during which the customer is kept from responding. The salesperson then offers a better deal by either lowering the price or adding a bonus product. That’s-not-all is a variation on door-in-the-face. Whereas the latter begins with a request that will be rejected, however, that’s-not-all gains its influence by putting the customer on the fence, allowing them to waver and then offering them a comfortable way off.

Burger (1986) demonstrated the technique in a series of field experiments. In one study, for example, an experimenter-salesman told customers at a student bake sale that cupcakes cost 75 cents. As this price was announced, another salesman held up his hand and said, “Wait a second,” briefly consulted with the first salesman, and then announced (“that’s-not-all”) that the price today included two cookies. In a control condition, customers were offered the cupcake and two cookies as a package for 75 cents right at the onset. The bonus worked magic: Almost twice as many people bought cupcakes in the that’s-not-all condition (73 per cent) than in the control group (40 per cent).

6. The Sunk Cost Trap

Sunk cost is a term used in economics referring to nonrecoverable investments of time or money. The trap occurs when a person’s aversion to loss impels them to throw good money after bad, because they don’t want to waste their earlier investment. This is vulnerable to manipulation. The more time and energy a cult recruit can be persuaded to spend with the group, the more “invested” they will feel, and, consequently, the more of a loss it will feel to leave that group. Consider the advice of billionaire investor Warren Buffet: “When you find yourself in a hole, the best thing you can do is stop digging” (Levine, 2003).

7. Scarcity & Psychological Reactance

People tend to perceive things as more attractive when their availability is scarce (limited), or when they stand to lose the opportunity to acquire them on favourable terms (Cialdini, 2008). Anyone who has encountered a willful child is familiar with this principle. In a classic study, Brehm and Weinraub (1977), for example, placed two-year-old boys in a room with a pair of equally attractive toys. One of the toys was placed next to a plexiglass wall; the other was set behind the plexiglass. For some boys, the wall was one foot high, which allowed the boys to easily reach over and touch the distant toy. Given this easy access, they showed no particular preference for one toy or the other. For other boys, however, the wall was a formidable two feet high, which required them to walk around the barrier to touch the toy. When confronted with this wall of inaccessibility, the boys headed directly for the forbidden fruit, touching it three times as quickly as the accessible toy.

Research shows that much of that two-year-old remains in adults, too. People resent being controlled. When a person seems too pushy, we get suspicious, annoyed, often angry, and yearn to retain our freedom of choice more than before. Brehm (1966) labeled this the principle of psychological reactance.

The most effective way to circumvent psychological reactance is to first get a foot in the door and then escalate the demands so gradually that there is seemingly nothing to react against. Hassan (1988), who spent many years as a higher-up in the “Moonies” cult, describes how they would shape behaviours subtly at first, then more forcefully. The material that would make up the new identity of a recruit was doled out gradually, piece by piece, only as fast as the person was deemed ready to assimilate it. The rule of thumb was to “tell him only what he can accept.” He continues: “Don’t sell them [the converts] more than they can handle . . . . If a recruit started getting angry because he was learning too much about us, the person working on him would back off and let another member move in…”

Media Attributions

- The graphic of the “Elaboration Likelihood Model” by Niosi, A. (2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA and is adapted from 12-3 Attitudes and Persuasion by Open Stax.

- The image of people waiting in a long line outside of a retail store is by Melanie Pongratz on Unsplash.

Text Attributions

- The sections under “Source Credibility”, “Source Attractiveness”, “Match-Up Hypothesis” (edited), and “Star Power” are adapted from Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time [PDF] by Saylor Academy which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

- The section under “Persuasion”; the section under “The Source of Persuasion” (Likeability section edited; excluding the last paragraph); the section under “Celebrity Endorsements”, and the sections under “Creatively Persuasive”, are adapted from Levine, R. V. (2019). “Persuasion: so easily fooled“. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI:nobaproject.com.

- The definition of “The Halo Effect” is adapted from “Module 4: The Perception of Others” by Washington State University which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The opening two paragraphs and the section under “The Effective Use of Persuasion by Apple to Drive Sales” are adapted from Principles of Social Psychology – 1st International Edition by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The section “Elaboration Likelihood Model” (including an edited image) is adapted from Spielman, R.N., Dumper K., Jenkins W., Lacombe A., Lovett M., and Perimutter M. (2014, Dec 8). Psychology is published by OpenStax under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- The “Student Op-Ed: How to be a Woman (according to the Susan G. Komen Foundation) is by Ventura, S. (2019) which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

References

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Brehm, S. S., & Weinraub, M. (1977). Physical barriers and psychological reactance: Two-year-olds’ responses to threats to freedom. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 830–836.

Celebrity Ads’ Impact Questioned. (2007, February 27). BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/somerset/6400419.stm.

Cialdini, R. B. (2008). Influence: Science and practice (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., and Walster E. (1972). What Is Beautiful Is Good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 285–90.

Ellevsen, G. (2018). Insincere Influencers Pay Price for Brand Infidelity. https://www.brandthropologist.net/insincere-influencers-to-pay-price-for-brand-infidelity/.

Fox, S. (1997). The mirror makers: A history of American advertising and its creators. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Friend, K., & Levy, D. T. (2001). Reductions in smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption associated with mass-media campaigns. Health Education Research, 17(1), 85-98.

Fuller, R. G., & Sheehy-Skeffington, A. (1974). Effects of group laughter on responses to humorous materials: A replication and extension. Psychological Reports, 35, 531–534.

Global Apple iPhone sales in the fiscal years 2007 to 2013 (in million units). (2014). Statista. http://www.statista.com/statistics/276306/global-apple-iphone-sales-since-fiscal-year-2007/.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Which Companies Have Been Dropped. (n.d.). GrabYourWallet. Retrieved June 1, 2018 from https://grabyourwallet.org/Which%20Companies%20Have%20Been%20Dropped.html.

Gupta, P. B., & Lord, K. R. (1998). Product placement in movies: The effect of prominence and mode on recall. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 20, 47–59.

Hassan, S. (1988). Combating cult mind control. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

iPhone 5S sales statistics. (2013). Statistic Brain. http://www.statisticbrain.com/iphone-5s-sales-statistics/.

Johnson, B. (2013). 10 things you should know about the global ad market. Ad Age. http://adage.com/article/global-news/10-things-global-ad-market/245572/.

Kahle, K.E. and Kahle, L.R. (2005). Sports Celebrities’ Image: A Critical Evaluation of the Utility of Q Scores [Working paper]. University of Oregon.

Kamins, M.A. (1990). An Investigation into the ‘Match-Up’ Hypothesis in Celebrity Advertising: When Beauty May Be Only Skin Deep. Journal of Advertising, 19( 1), 4–13.

Knanh, T.L. and Antonio, R. (2001, January 24). Web Sites Bet on Attracting Viewers with Humanlike Presences of Avatars. Wall Street Journal Interactive Edition.

Levine, R. (2003). The power of persuasion: How we’re bought and sold. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Meyer, A.R. (2019). Redemption of ‘Fallen’ Hero-Athletes: Lance Armstrong, Isaiah, and Doing Good while Being Bad. Religions, 10, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10080486.

Mowen, J. C., & Cialdini, R. B. (1980). On implementing the door-in-the-face compliance technique in a business context. Journal of Marketing Research, 17, 253–258.

Myers, D. (2011). Social psychology (10th ed.). New York, NY: Worth.

Neff, J. (2007, June 4). How Tupperware Made Itself Relevant Again. Advertising Age, 19.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of personality and social psychology, 35(4), 250.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change (pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1.

Pool, L. (Director). (2011). Pink Ribbons, Inc. [Film]. National Film Board of Canada.

Ross, R. P., Campbell, T., Wright, J. C., Huston, A. C., Rice, M. L., & Turk, P. (1984). When celebrities talk, children listen: An experimental analysis of children’s responses to TV ads with celebrity endorsement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 5, 185–202.

Solomon, M., White, K. & Dahl, D.W. (2017). Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having, Being Seventh Canadian Edition. Pearson Education Inc.

Ross Sorkin, A., Karaian, J., de la Merced, M., Hirsch, L. & Livni, E. (2001, January 11). Money Walks: Corporate America is rethinking its political donations. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/business/dealbook/corporate-political-donations.html