Chapter 26: Structural Relationship Violence

Balbir Gurm and Carson Adams

Learning Objectives

By reading the chapter, the person will be able to:

- Define relationship violence

- Describe structural violence

- Identify the role of the MIC & PIC in relationship violence

- Explain the overlap of systemic and relationship violence

Key Takeaways

- The Medical Industrial Complex has a longstanding history with oppressed communities, including a legacy of denying services, medical experimentation, pathologized treatment, and forced sterilization (Leaving Evidence, 2015).

- Ableism is a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed,’ and can become violent when end of life policies are prioritized over treatment (Odette, 2013; National Survivor Network, n.d.).

- The Prison Industrial Complex describes how prisons are designed to rely on mass incarceration, making it essential to continue developing laws that criminalize new behaviours (National Survivor Network, n.d.).

- Medical Industrial Complex is designed to keep individuals sick and employ professionals. It is set up to discriminate and privilege and preserve those who society considers more worthy.

- Examples of structural and systemic racism as being political disempowerment, segregation, financial practices, environmental injustice, the criminal justice system, and data aggregation (Braveman, 2022).

- Experiences of interpersonal violence are both directly and indirectly caused by the bureaucracies within institutions that did not respond to their needs, and instead disrespected and mistreated them further exacerbating their marginalization (Macassa, 2023; Montesanti & Thurston, 2015).

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone who has a bond or relationship with the offender(s). In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), interpersonal violence (IVP), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology- facilitated coercive control, honour killing, gang violence, social isolation, circulation of intimate images and workplace violence. Violence can be perpetrated by persons in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships in which the victim is transgender (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, xenophobia, homophobia and ageism. It can span the entire age spectrum and it may start in-utero and end with the death of the victim.

This chapter highlights the systematic way that structures discriminate and reproduce inequities in society. It highlights the complexities of systems and why it is difficult to change the culture that accepts relationship violence.

Structural Violence Definitions

Structural violence refers to systematic ways in which social structures harm or otherwise disadvantage individuals. This concept, introduced by Johan Galtung, emphasizes that violence is not only physical but can also be embedded in societal institutions, leading to unequal access to resources, opportunities, and rights.

The concept of structural violence has evolved over time, drawing from various disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, and political science. It is rooted in the understanding that violence is not only physical but can also be embedded in the very fabric of society, perpetuating inequality and oppression. It highlights how societal structures perpetuate inequality and oppression, manifesting in interpersonal violence. By examining the link between structural violence and relationship violence, we can better address the root causes and develop more effective interventions. In previous chapters you may have read about some of the structural elements that contribute to RV, they are included below:

- Structural violence creates and perpetuates power imbalances within society. These imbalances often manifest in interpersonal relationships, where one individual may exert control and dominance over another. For example, patriarchal structures that devalue women and uphold male dominance can lead to domestic violence, where men feel entitled to control and abuse their female partners.

- Economic inequality, a form of structural violence, can exacerbate relationship violence. Financial stress and dependency can create tensions within relationships, leading to conflicts and abuse. For instance, individuals in economically disadvantaged situations may feel trapped in abusive relationships due to financial dependency on their partner.

- Racial and ethnic discrimination, embedded in societal structures, can also contribute to relationship violence. Marginalized racial and ethnic groups often face higher levels of stress and trauma due to systemic racism, which can increase the likelihood of violence within relationships. Additionally, cultural stigmas and lack of access to support services can prevent victims from seeking help.

- Gender inequality is a significant factor in relationship violence. Societal norms that devalue women and uphold patriarchal structures contribute to the acceptance and perpetuation of gender-based violence. Women and gender minorities are often at a higher risk of experiencing violence in their relationships due to these ingrained power dynamics.

- Health disparities, driven by structural violence, can also play a role in relationship violence. Individuals with untreated mental health issues or substance abuse problems, often resulting from lack of access to healthcare, may be more prone to perpetrating or experiencing violence. Additionally, stress and trauma from health disparities can strain relationships, leading to conflicts and abuse. From community stories, we understand Indigenous people and people of colour are often not investigated, misdiagnosed and sent home.

Case Studies

Domestic violence is a prevalent form of relationship violence that is deeply influenced by structural violence. Economic dependency, lack of access to support services, and societal norms that condone male dominance all contribute to the perpetuation of domestic violence. For example, women in economically disadvantaged communities may stay in abusive relationships due to financial dependency and lack of resources to leave. They may also stay due to stigma that blames women for the violence inflicted on them. Perpetrators say “she asked for it…she disrespected me…she did not have my dinner made” etc.

Bullying in schools is another form of relationship violence that can be linked to structural violence. Socioeconomic disparities, racial discrimination, and gender norms can all contribute to bullying behaviours. Students from marginalized backgrounds may be more likely to experience bullying, and the stress and trauma from such experiences can have long-term effects on their mental health and academic performance. The accepted isms of Canadian Society (see power and privilege wheel in chapter 3) allow some individuals to have privilege and others to be oppressed. The acceptance of these inequities provides permission for those with privilege to inflict harm on those who are oppressed.

Workplace harassment, including sexual harassment and discrimination, is a form of relationship violence that occurs in professional settings. Structural violence in the form of gender inequality and power imbalances within organizations can create environments where harassment is tolerated or overlooked. Victims may feel powerless to report harassment due to fear of retaliation or lack of support from management. For example, international South Asian students and immigrant women fear they will be reported so rarely report the abuse they suffer at the hands of their employers and landlords. See chapter 21 and chapter 24.

Impact on Society

Psychological and physical health effects that result from relationship violence are profound and far-reaching. Victims of relationship violence often experience trauma, anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. They also can experience physical effects such as hypertension, cancer, diabetes, arthritis and many other chronic conditions. These effects can be compounded by the stress and trauma associated with structural violence, creating a cycle of violence and mental health challenges. See chapter 2 and chapter 8.

Social and economic consequences are significant among instances of relationship violence. It can lead to strained social relationships, decreased productivity, and increased healthcare costs. Communities affected by high levels of relationship violence may also experience higher rates of crime and social instability. Access the chapter on gang violence and read some of the impacts.

The long-term implications of relationship violence include entrenched social inequalities and persistent cycles of violence. Addressing these issues requires systemic change and sustained efforts to dismantle oppressive structures and promote social justice.

Structural Violence Through the Medical Industrial Complex (MIC)

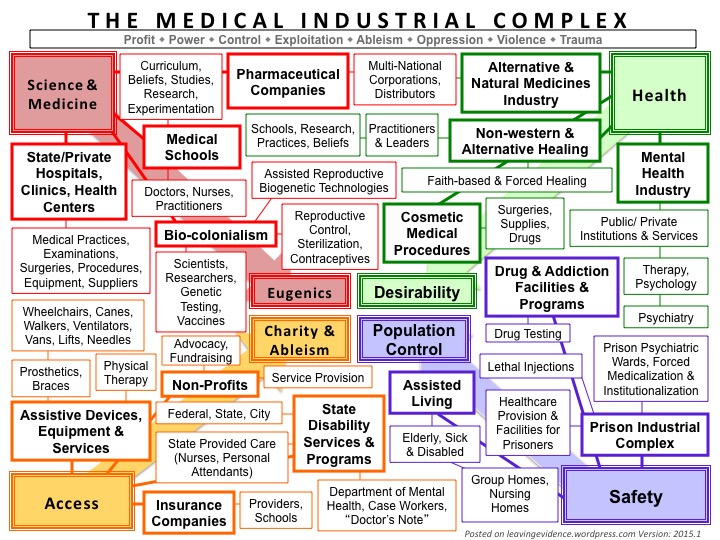

The Medical Industrial Complex is a system that is deeply tied to colonialism and the forced control over a group of people, as well as capitalism with the ultimate goal of generating profit. The visual below outlines the 4 distinct sections that make up the underlying core motivations of the MIC: Eugenics, Charity and Ableism, Population Control and Desirability. What allows the MIC to continue to be profitable is how Eugenics anchors Science and Medicine, how Desirability anchors Health, how Charity and Ableism anchor Access, and how Population Control anchors Safety in the name of Science and Medicine (Leaving Evidence, 2015). The diagram below shows the complexities of systems and organizations and how they are entrenched in each other, neither is independent. It explains why it is almost impossible to change one system.

In the chapter titled “The system Isn’t Broken It’s Working as Designed,” Zena Sharman explores the intentional functionings of the Medical Industrial Complex in The Care we Dream Of: Liberatory and Transformative Approaches to LGBTQ+ Health:

The idea that the system is broken presumes the existence of a prior state of wholeness and functioning that needs to be restored -if we can just get back to this place, things will get better. Learning from the transformative justice movement…, in order to build safer communities we have to transform the conditions that lead to violence in the first place – what conditions lead someone to steal, rape, or otherwise cause harm, like poverty or sexism. As I’ve engaged more deeply in learning about transformative justice, abolition, healing justice, disability justice, and related concepts like the MIC, I’ve come to understand the insufficiency of the idea that our goal should be to fix a broken health system. It’s insufficient because it bypasses the truth that the system isn’t broken; it’s working as designed. (p 109)

The systems such as healthcare, social and justice are working extremely well to perpetuate and grow themselves. The problem is not that the system isn’t working, but it is not the system we need. We need systems that support equity and inclusion and not oppression and privilege.

Violence Against Disabled People Perpetrated by the Medical Industrial Complex

Ableism is a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other, according to the National Survivor Network. Fran (2021) identifies how ableism can become violent when end of life policies are prioritized over treatment:

Ableism as a form of violence is seen in decision making surrounding DNR (do not resuscitate) orders. People with disabilities are often coerced to sign these orders before going into the hospital or to sign under conditions where few other options are presented that would ensure they had access to medical care and supports… The underlying message surrounding ‘assisted suicide’, ‘DNR’ directives and the denial of medical care for women with disabilities, reflects larger systemic prejudices and other barriers that influence perceptions about whose life is valued, which in turn, influences who has responsibility for decisions about “ending life” and how those decisions are made.

Greene (2023) identifies mental illness as inherently political, due to its embedding into social relations that benefit from capitalistic values such as monetization, exploitation, control, and oppression. Additionally, Hardy (2021) claims that the relationship between physical and mental health-care seekers and biomedical providers remains a dynamic that fundamentally builds off of those values. Sharman (2021), explores how these capitalistic values and ableist assumptions structurally manifest in the MIC:

Health systems are built around a set of assumptions about health and illness, disability, and cure, who is and isn’t deserving of care, and who does and does not have a “good” body. Though it’s often held up as a universal good and something to strive for, health is not a neutral, objective, or universal concept. The meaning of “health” is constructed and shifts depending on where and when it’s created, and by whom… Further, the designation of some people, communities, and populations as “healthy” and others as “unhealthy” is entangled with systemic oppression and social control. (p 96)

These systems define who is healthy or unhealthy and who is valued and who is not. These systems are entangled in white supremacy and history of colonization in Canada and other colonized countries. Whiteness is an unearned privilege in the systems in Canada. This makes it difficult for Indigenous people and those persons of colour to be seen as equal and worthy. I draw on my own experience as a women of colour and observe that whitenees is entangled in every public system.

Intersectional Violence Perpetrated by the Medical Industrial Complex

Oppressed communities have a longstanding history with the MIC, including a legacy of denying services, medical experimentation, pathologized treatment, forced sterilization, and more. This relationship is outlined by the language used to define those in treatment and from a lack of culturally safe services including the erasure of Indigenous healing (Leaving Evidence, 2015). Sharman (2021) also touches on the LGBTQ+ perspective within the MIC:

LGBTQ+ people consistently report experiencing discrimination in health care settings and face persistent barriers to accessing health care. Some people avoid health care altogether because the risk of being harmed by homophobia, biphobia, transmisogyny, transphobia, racism, ableism, fatphobia, and other forms of discrimination feels greater than the health concern that might drive them to seek care in the first place. All of this contributes to the health disparities faced by the LGBTQ+ community, disparities that are worse for anyone whose body bears the brunt of systemic oppression. This is no accident; it is a predictable outcome of a health system rooted in normative ideals of health and illness that often exclude and harm those who fail to conform to those ideals. (p 110)

Again, gender minority individuals are seen as less than, not heterosexual, because they are different so they are oppressed.

Structural Violence Through the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC)

The Prison Industrial Complex describes how prisons are designed to rely on mass incarceration, making it essential to continue developing laws that criminalize new behaviours. Funding that is directed into supporting the carceral system draws funding from social programs that could reduce both crime and incarceration, contributing to a cycle that perpetuates state-sanctioned and legalized slavery. BIPOC are the most affected by the PIC and are often the main targets of criminalization and incarceration. IPOC is an acronym for “Indigenous People and People of Color,” and is a term used to acknowledge that even among “people of colour” there are differences in the ways people experience racism (National Survivor Network, n.d.). In Canadian history, there was legislation, to keep Canada White. Some examples are: Indigenous people were separated from families and placed in residential schools so they would lose their culture and language, Chinese were charged an entry head tax to deter them from entering Canada and Indians were legislated to come to Canada without a fuel stop anywhere when it was an impossibility with the technology of the day to prevent them from entering Canada. These are all examples of racist government policies.

Braveman and colleagues (2022) identify some examples of structural and systemic racism as being political disempowerment, segregation, financial practices, environmental injustice, the criminal justice system, and data aggregation. Political disempowerment includes voter suppression, and gerrymandering through the deliberate redrawing of electoral districts. Segregation includes the designation of public space based on race. Certain discriminatory financial practices include creating obstacles to home ownership through, and in addition to predatory payday loans and cheque cashing services. Environmental injustice includes selectively locating projects with adverse health effects near communities of colour. The criminal justice system participates in discriminatory policing and sentencing practices, often restricting future employment, housing, and voting opportunities of the incarcerated. Data aggregation includes ignoring underrepresented populations when creating policies that will negatively affect them.

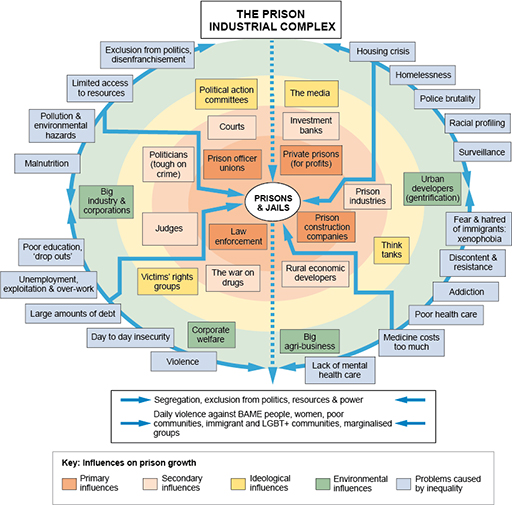

The diagram below shows how the state and issues of harm are intertwined within the Prison Industrial Complex. Particularly how inequalities such as poor education, racial profiling, debt, and unemployment increase the risk for incarceration, as well as how exclusions from policy limits the influence of those most likely to be imprisoned, that being marginalized groups (The Open University, n.d.).

The justice system in its current form is working well to perpetuate and grow. What is needed is a different justice system that doesn’t racially profile individuals. In Canada, the prison system consists of one-third Indigenous population when Indigenous people are only 5% of Canada’s population (Statistics Canada, 2022).

Intersectional Violence Perpetrated by the Prison Industrial Complex

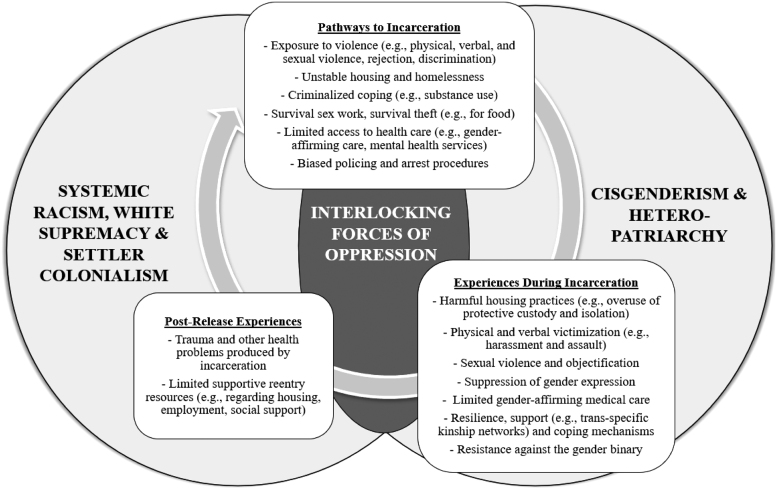

The venn diagram below was developed from qualitative data from 12 semistructured interviews with formerly incarcerated trans women who had been incarcerated in sex-segregated male facilities. System racism, white supremacy, settler colonialism, as well as cisgenderism and the heteropatriarchy are identified as the interlocking forces of oppression that operate through pathways to incarceration, experiences during incarceration, and postrelease experiences, revealing the “oppression-to-incarceration cycle” (Clark et al, 2023).

Recidivism rates indicate that the PRI is working as designed to ensure the continued marginalization of “undesirable populations” (Ortiz, 2019). For example, transgender people are especially at risk for contact with the criminal legal system, as well as harassment and violence once inside prison (Kelsie & Peirce, 2024). Kelsie and Peirce (2024) interviewed 280 transgender people in state prisons where 22% of respondents were housed in restrictive housing units and 89% had experienced solitary confinement at some point during their incarceration. Additionally, 31% named harassment, threats, and attacks against their identity as a top reason they felt unsafe in prison, and more than 53% reported experiencing sexual assault at some point during their prison sentence.

Understanding how the Thirteenth Amendment did not actually abolish slavery, but instead relocated it into the criminal justice system and private prisons, helps to explain why the U.S. incarceration rate of 639 per 100,000 people is 5-10 times higher than other industrialized democracies (World Population Review, 2024; United States Congress, n.d.). This relocation as well as the U.S. tax code does not classify prison labor as employment, making it permissible to force inmates to work for no or criminally low pay. On average inmates are paid $0.93 USD per day, highlighting how policing and prisons are inseparable parts of modern slavery, and how the current public objection to the systems and policies that allow it, are indicative of eighteenth and nineteenth century abolitionism. (Woods, 2021; Prison Policy Initiative, n.d.)

During slavery, “abolitionists” were people who advocated to end the slave trade and chattel slavery. Notably, when the 13th amendment passed it abolished all slavery except as a punishment for a crime, which is another contributor to current day instances of forced labour (National Survivor Network, n.d.). In the spirit of the prison reentry industry working to ensure the continued marginalization of “undesirable populations,” individuals with felony convictions are often stripped of their right to vote. Felons may lose their vote permanently in 9 states, have their vote restored after prison, parole and probation in 15 states, have their vote restored after prison and parole in 1 state, have their vote restored after prison in 23 states, and may vote from prison in 2 states. See which policies apply to each state. In Canada, all prisoners have the right to vote in Canadian elections.

Structural Violence Overlap With Interpersonal Violence

The DisCrit Theoretical Framework is grounded in both disability studies and critical race theories where the discussion of “abnormal” bodies and minds is not focused on a single identity category or an ideological system related to a particular identity (Mueller, 2019). DisCrit values multidimensional identities, considers legal and historical aspects used together or separately to deny rights, and recognizes whiteness and ability as property. Kimberly Crenshaw (1989) coined the term intersectionality as a response to white feminists. She stated that identity is tied up in race, gender, class and other individual characteristics that work together. That being said, DisCrit theory or Crenshaw’s intersectionality theory can be helpful tools to analyze the implications of what are considered to be “normal” and “abnormal” bodies within and between specific identities. Including how Muller (2019) deduced that disabled people, according to the relatively small body of data collected on this demographic, experience serious violence at a rate almost twice that of the general population.

Between 6% and 22% of abortion patients experience intimate partner violence, so access to the full spectrum of reproductive health care including abortion, and improving accessibility to abortion care requires careful attention to violence at all socioecological levels (Neilson et al., 2023). Survivors of IPV are more likely to experience sexual violence and reproductive coercion, including contraceptive sabotage, pressure to become and stay pregnant, and occasionally, although less commonly, pressure to have an unwanted abortion. (Pallitto et al., 2013; Chibber et al., 2014; Samankasikorn et al., 2019). In the same way IPV significantly increases the odds of unintended pregnancy and abortion, negative attitudes about people with disabilities and other marginalized identities, such as IPOC and the LGBTQ2SIA+ community, dictate how individuals are perceived and treated (Gault et al., 2023).

Muños and colleagues (2023) identify isolation, poverty and housing insecurity, and lack of access to justice as structural barriers that serve as risk factors for disabled women. This uncovers an interrelationship between the determinants of health and interpersonal violence, making disabled women particularly at risk. (Muños et al., 2023; Montesanti & Thurston, 2015) Gender as a symbolic institution, as well as structural or systemic violence can lead to encouraging interpersonal violence, especially against women. In order to improve future interventions aimed at minimizing revictimization and improving the health outcomes among victimized women and men, a better understanding of structural violence and how it intersects with IPV is required. It is also significant how women’s experiences of interpersonal violence are both directly and indirectly caused by the bureaucracies within institutions that did not respond to their needs, and instead disrespected and mistreated them further exacerbating their marginalization (Macassa, 2023; Montesanti & Thurston, 2015). Women tell us that the justice system revictimizes them.

Structural Violence Prevention & Resources

To learn why we can’t achieve peace without addressing structural violence, watch Temi Mwale: We can’t achieve peace without addressing structural violence (Temi, 2018). To learn how to respond to structural violence framework, watch How to Respond to Structural Violence Frameworks (Triumph Debate, 2021).

| Resource | Summary | For more information |

|---|---|---|

| Racist Incident Helpline | Racist Incident Helpline (1-833-457-5463)

BC Mental Health & Crisis Response (310-6789) KUU-US Crisis Line (1-800-588-8717) Métis Crisis Line (1-833-638-4722) Kids Help Phone (1-800-668-6868) |

Visit Helpline Information and Opportunities for Service Providers.

(Racist Incident Helpline, n.d.) |

| Victim Services BC | Find victim services, transition houses, and counselling resources.

Victim Link Helpline (1-800-563-0808) |

Contact 211-VICTIMLINKBC@UWBC.CA

(VictimLinkBC, 2023) |

| Complex Trauma Services | Find treatments and resources for systemic trauma. | Please find the treatment that’s right for you, and visit the complex trauma resource materials.

(Complex Trauma Resources, 2024) |

The Oregon Coalition Against Domestic & Sexual Violence and their Prevention Through Liberation project places importance on the lived experience of oppression in developing a communities’ ability to self-define what effective sexual and domestic violence prevention means and how it can be carried out. Anti-oppression values include trust, respect, intimacy, consent, honesty, mutuality, shared power, self-determination, intergenerational community, shared responsibility, partnership, and interdependence (Adkison-Stevens & Timmons, 2018).

Anti-oppression practices that promote violence prevention include:

- Valuing and uplifting positive relationships between youth and adults

- Restoring community norms and resiliency

- Grounded empowerment, in contrast to exploitative power over others

- Shoring up against exploitation and harm

- Moving upstream

- Deep listening and deep learning

- Understanding of historical trauma, woundedness, and healing

- Understanding of equity versus equality

- Collaboration

- Organizational and individual allyship

- Reframing concepts of leadership, organizational structures, and outcomes

- Navigating discomfort (Adkison-Stevens & Timmons, 2018)

Some examples of what such programming could look like include projects that:

- Restore and strengthen family systems (e.g. through youth and elder discussion circles on sex and relationships)

- Generate, cultivate and communicate positive, empowered, resilient and self-determined cultural norms (through discussion, videos, multi-media, social media, etc.)

- Work with incarcerated youth or adults around power and sexuality, restoring their sense of empowerment after being targeted by deeply disempowering systems, and decreasing their likelihood to use sex to gain power over others

- Promote and cultivate youth-led content and messaging designed to educate families about sexual health, positive sexuality and relationships (e.g., for Deaf/hard of hearing youth)

- Support restorative and culturally grounded parenting practices (Adkison-Stevens & Timmons, 2018)

The American Health Association policy statements listed below relate directly to racism, violence, and community health workers:

- APHA Policy Statement 20189: Achieving Health Equity in the United States

- APHA Policy Statement 20185: Violence is a Public Health Issue: Public Health is Essential to Understanding and Treating Violence in the U.S.

- APHA Policy Statement 201414: Support for Community Health Worker Leadership in Determining Workforce Standards for Training and Credentialing

- APHA Policy Statement 20091: Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities

- APHA Policy Statement 200115: Recognition and Support for Community Health Workers’ Contribution to Meeting our Nation’s Health Care Needs (APHA, 2022)

References

Adkison-Stevens, Choya., Timmons, Vanessa. (2018). Prevention Through Liberation: Theory and Practice of Anti-Oppression as Primary Prevention of Sexual and Domestic Abuse. Oregon Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. https://www.ocadsv.org/resources/prevention-through-liberation-theory-and-practice-of-anti-oppression-as-primary-prevention-of-sexual-and-domestic-violence/

American Public Health Association. (2022). A Strategy to Address Systemic Racism and Violence as Public Health Priorities: Training and Supporting Community Health Workers to Advance Equity and Violence Prevention. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2023/01/18/address-systemic-racism-and-violence

Braveman, A. Paula., Arkin, Elaine., Proctor, Dwayne., Kauh, Tina., Holm, Nicole. (2022). Systemic And Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, And Approaches To Dismantling. Health Affairs 2022 41:2, 171-178. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394

Carney, M., Buttell, B., & Dutton, D. (2007). Women who perpetrate intimate partner violence: A review of the literature with recommendations for treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12, 108 –115. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222426549_Women_Who_Perpetrate_Intimate_Partner_Violence_A_Review_of_the_Literature_With_Recommendations_for_Treatment

Chestnut, Kelsie., Peirce, Jennifer. (2024) Advancing Transgender Justice: Illuminating Trans Lives Behind and Beyond Bars [PDF]. Vera Institute of Justice. https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/publications/advancing-transgender-justice.pdf

Chibber K. S., Biggs M. A., Roberts S. C. M., Foster D. G. (2014). The role of intimate partners in women’s reasons for seeking abortion. Women’s Health Issues, 24(1), e131‐e138. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24439939/

Clark, K. A., Brömdal, A., Phillips, T., Sanders, T., Mullens, A. B., & Hughto, J. M. W. (2023). Developing the “Oppression-to-Incarceration Cycle” of Black American and First Nations Australian Trans Women: Applying the Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice Framework. Journal of correctional health care : the official journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 29(1), 27–38. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10081706/

Complex Trauma Resources. (2024). Structural Violence. https://www.complextrauma.org/glossary/structural-violence/

Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989) Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiractist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum (1989)1, Article 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

Ezell, M. Jerel. (2024). The Health Disparities Research Industrial Complex [PDF]. Social Science & Medicine, Volume 351, 116251, ISSN 0277-9536. https://cdn2.psychologytoday.com/assets/2023-11/Ezell%202023_The%20Health%20Disparities %20Research%20Industrial%20Complex.pdf

Gault, Gabrielle., Wetmur, Alison., Plummer, Sara., Findley, A. Patricia. Violence Against People With Disabilities: Implications For Practice. Social Work Practice and Disability Communities: An Intersectional Anti-Oppressive Approach. Pressboks. https://rotel.pressbooks.pub/disabilitysocialwork/chapter/violence-against-people-with-disabilities-implications-for-practice/

Greene, E. M. (2023). The Mental Health Industrial Complex: A Study in Three Cases. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 63(1), 84-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167819830516

Hardy, Kristen. (2021). Pulling Up the Tangled Roots: Biomedical Oppression and Fat Liberation. The Polyphony – Conversations Across Medical Humanities. https://thepolyphony.org/2021/11/16/pulling-up-the-tangled-roots-biomedical-oppression-and-fat-liberation/

Leaving Evidence. (2015). Medical Industrial Complex Visual. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2015/02/06/medical-industrial-complex-visual/

Lee, X. Bandy. (2016) Causes and cures VII: Structural violence, Aggression and Violent Behavior. Science Direct, Volume 28, Pages 109-114, ISSN 1359-1789. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359178916300441

Lee, X. Bandy. (2019). Structural Violence. In Violence, B.X. Lee (Ed.). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119240716.ch7

Macassa G. (2023). Does Structural Violence by Institutions Enable Revictimization and Lead to Poorer Health Outcomes?—A Public Health Viewpoint. Annals of Global Health. 89(1): 58, 1–7. https://annalsofglobalhealth.org/articles/10.5334/aogh.4137

Montesanti, S.R., Thurston, W.E. (2015). Mapping the role of structural and interpersonal violence in the lives of women: implications for public health interventions and policy. BMC Women’s Health 15, 100. https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-015-0256-4

Mueller, Carlyn., Forber-Pratt, Anjali., Sriken, Julie. (2019). Disability: Missing from the Conversation of Violence [PDF]. Black Feminist Pedagogies. http://www.blackfeministpedagogies.com/uploads/2/5/5/9/25595205/disability-_missing_from_the_conversation_of_violence_carlyn_o._mueller%E2%88%97_university_of_washington_anjali_j._forber-pratt_and_julie_sriken.pdf

Muñoz, Yolanda., Lévesque, Martine., Roy, Laurence., Labrecque-Lebeau, Lisandre. (2023). Intimate Partner Violence and Disability: Addressing Systemic Barriers. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2023/11/04/intimate-partner-violence-and-disability-addressing-systemic-barriers/

Mwale, Temi. (2018). We can’t achieve peace without addressing structural violence. TEDx. https://www.ted.com/talks/temi_mwale_we_can_t_achieve_peace_without_addressing_structural_violence?subtitle=en

National Survivor Network. (n.d.). Definitions. https://nationalsurvivornetwork.org/definitions/

Neilson, E. C., Ayala, S., Jah, Z., Hairston, I., Hailstorks, T., Vyavahare, T., Gonzalez, A., Hernandez, N., Jackson, K., Bailey, S., Hall, K. S., Diallo, D. D., & Mosley, E. A. (2023). “If I Control Your Body, I Can Fully Control You”: Interpersonal and Structural Violence Findings from the Georgia Medication Abortion Project. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 47(4), 462-477. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/03616843231175388

Odette, Fran (November 2013). Ableism – A Form of Violence Against Women. Critical Reflections by Fran Odette. Learning Network Brief (11). London, Ontario: Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children. https://gbvlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/briefs/brief-11.html

Ortiz, J. M., & Jackey, H. (2019). The System Is Not Broken, It Is Intentional: The Prisoner Reentry Industry as Deliberate Structural Violence. The Prison Journal, 99(4), 484-503. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0032885519852090

Pallitto C. C., García-Moreno C., Jansen H. A. F. M., Heise L., Ellsberg M., Watts C. (2013). Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 120(1), 3‐9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22959631/

Prison Policy Initiative. (n.d.). Section III: The Prison Economy. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/prisonindex/prisonlabor.html

ProCon.org. (2023). State Voting Laws & Policies for People with Felony Convictions. Britannica, https://felonvoting.procon.org/state-felon-voting-laws/

Racist Incident Helpline. (n.d.). Experienced racism in BC?. https://racistincidenthelpline.ca/?gad_source=1&gbraid=0AAAAABREGO4FDJoMxV5FPIAH-VUz3NFy9&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu-63BhC9ARIsAMMTLXQwQ-og8hAuhoRryrGyb39TMcnyl8NGvg_sMqZckd7yvJzUWFx9C3waAkOAEALw_wcB

Rollè, L., Giardina, G., Caldarera, A. M., Gerino, E., & Brustia, P. (2018). When Intimate Partner Violence Meets Same Sex Couples: A Review of Same Sex Intimate Partner Violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1506. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506/full

Samankasikorn W., Alhusen J., Yan G., Schminkey D. L., Bullock L. (2019). Relationships of reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence to unintended pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 48(1), 50‐58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30391221/

Statistics Canada. (2022, April 20). Adult and youth correctional statistics, 2020/2021. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220420/dq220420c-eng.htm

The Open University. (n.d.). 3.1 The prison industrial complex. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/questioning-crime-social-harms-and-global-issues/content-section-3.1

The Scottish Trans Alliance. (2010). https://www.scottishtrans.org/

Triumph Debate. (2021). How to Respond to Structural Violence Frameworks – Triumph Debate Workshop Demo Lecture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbHe4jYkxoI

United States Congress. (n.d.). Constitution of the United States. Thirteenth Amendment. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-13/

VictimLinkBC. (2023). Victim Services in B.C.. https://victimlinkbc.ca/?gad_source=1&gbraid=0AAAAABvKg4PLDCRZ8DoANs3gH5K4n79DQ&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu-63BhC9ARIsAMMTLXT_wzLZqRqCVFtdM404tY4PMGgebju44rTRQ9G-b6Phhtb6MsoU4rgaAvOPEALw_wcB

Woods, P. Tryon. (2021). Slavery and the U.S. Prison System. Global Policy Journal. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/06/05/2021/slavery-and-us-prison-system

World Population Review. (2024). Incarceration Rates by Country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/incarceration-rates-by-country

Zena Sharman. (2021). The Care We Dream Of: Liberatory and Transformative Approaches to LGBTQ Health. Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver. https://arsenalpulp.com/Books/T/The-Care-We-Dream-Of