Chapter 25: Gang Violence: Death is Always Close By

Dianne Symonds

Learning Objectives

By reading the chapter, the person will be able to:

- Define relationship violence

- Describe the antisocial behavior of gangs in regard to relationship violence

- Explain how gangs teach members to be violent

- List how girls/women can become associated with gangs

- Articulate the types of relationship violence that occurs in gangs

Key Takeaways

- Gangs promote relationship violence. They are formed by groups of people who must give up their compassion, their ability to negotiate, their independence, and their hope. They exchange these for a violent atmosphere of obedience gained by forcing members to participate in a variety of anti-social behaviours including selling drugs, raping women, violence and killing.

- The greatest risk of being a victim of gang violence comes from two sources ─ rival gangs and one’s own gang members. It is ironic that joining a gang for safety can instead dramatically increase the risk of being violently attacked. This is true for men and women.

- Persons who have a casual friend or close family member in a gang are at risk for violence including death.

- Gangs teach people to be violent. They use a variety of strategies including dehumanizing and blaming their victim, minimiz ing the true nature of their acts, and attributing responsibility to the person who ordered the violence.

- Some girls/women are associate members but more and more are becoming full gang members themselves. They can be drive-by shooters, enforcers or have any other role in a gang.

- All girl gangs are becoming more frequent.

- Girls/women are passed around for sex in many gangs.

- Men in many gangs are trained to be hypermasculine and to have a desire to have sexual intercourse anytime frequently committing sexual violence.

Relationship violence is any form of physical, emotional, spiritual and financial abuse, negative social control or coercion that is suffered by anyone who has a bond or relationship with the offender(s). In the literature, we find words such as intimate partner violence (IPV), interpersonal violence (IVP), neglect, dating violence, family violence, battery, child neglect, child abuse, bullying, seniors or elder abuse, stalking, cyberbullying, strangulation, technology- facilitated coercive control, honour killing, gang violence, social isolation, circulation of intimate images and workplace violence. Violence can be perpetrated by persons in opposite-sex relationships (Carney et al., 2007), within same-sex relationships (Rollè et al., 2018) and in relationships in which the victim is transgender (The Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010). Relationship violence is a result of multiple impacts such as taken for granted inequalities, policies and practices that accept sexism, racism, xenophobia, homophobia and ageism. It can span the entire age spectrum and it may start in-utero and end with the death of the victim.

In this chapter, we discuss gang violence. We discuss the violent behavior of gangs, their risk of committing abuse and how they are taught to comply with taking part in violent behavior. Gangs engage in all types of relationship violence: physical, sexual, emotional, financial and spiritual. Although some girls and young women are associate gang members, they are at risk of sexual exploitation and violence. In recent years, the number of all girl gangs has increased.

Physical violence in gangs can take many forms. From acid throwing in London, to wielding a knife in Chicago, to firing an automatic weapon in Vancouver, violence is a particularly disturbing aspect of gang life. In some gangs, it is a way of life. It creates an atmosphere of fearfulness in the public who know blameless bystanders can get caught in the crossfire. Some innocents are killed. But overwhelmingly, it is the gang members who die. Here are just a few examples.

Gang Violence in Vancouver

In Vancouver, retaliatory gang killings are not uncommon. In 2016, neighbours living in rural Langley, near Vancouver, found the horribly mutilated body of a gang member. He was later identified as Shaun Clary and he expected to die. In his picture on Facebook, these words are tattooed on his back:

“This is who I am. This is what the world made me. I don’t give a fuck whether you love me or hate me. I’m gonna die like that forever at war. Hated by most, loved by few, respected by all.”

The respect he so craved was never earned. (Bolan, 2016)

Gangs in Vancouver use Firearms

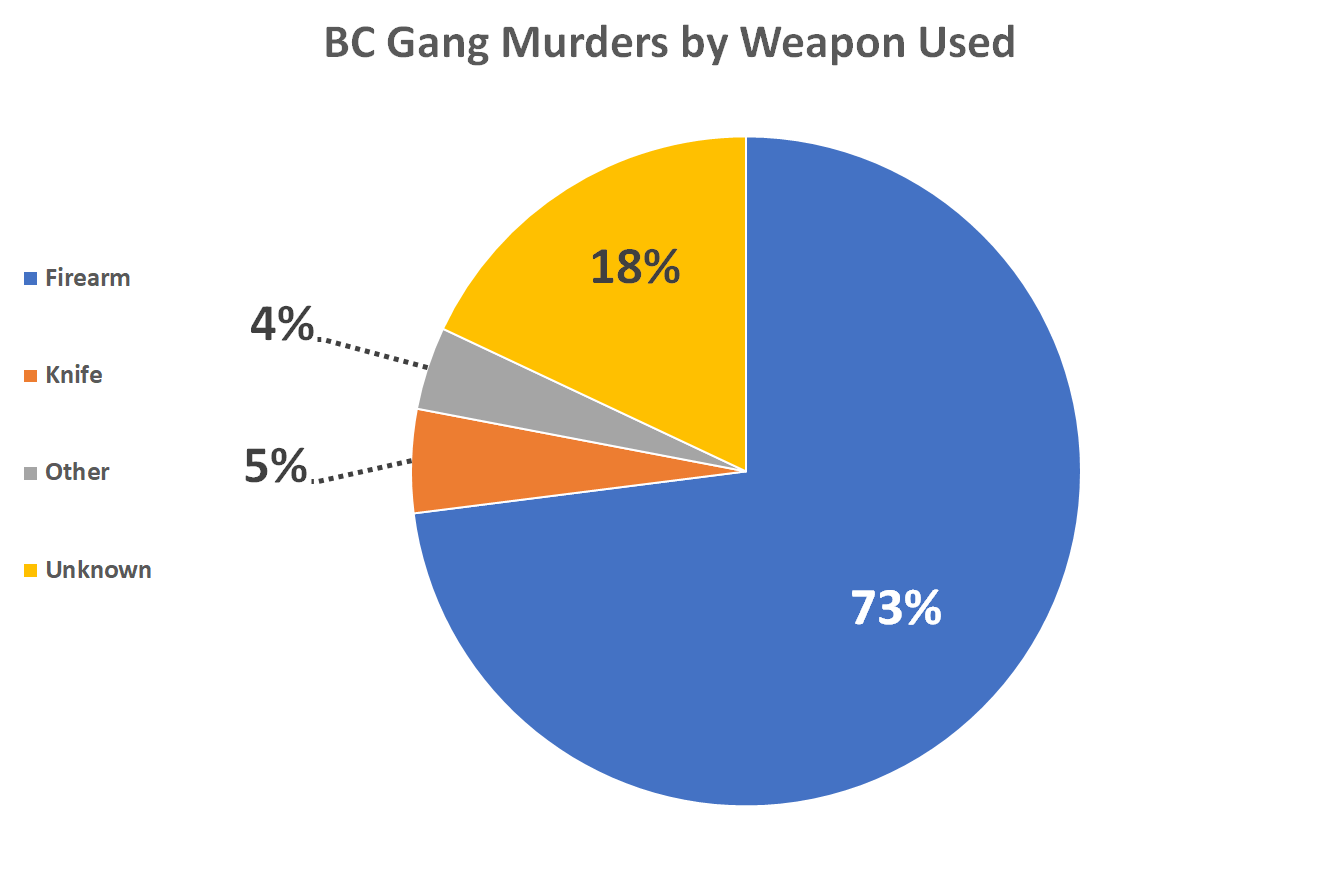

As noted in a media analysis (Jingfors, Lazzano & McConnell, 2015), Canadian guns laws are relatively strict. As a result, firearms are used in only 2.4 percent of all violent crimes across Canada. However, they are the weapons of choice for gangs in the province of British Columbia especially around Vancouver. Illegal guns, usually from the US, were used in 73 percent of their killings. See the chart below from Jingfors, Lazzano & McConnell (2015), p. 6.

These authors noted 80 percent of these inter-gang murders were conducted in public places putting the general public at risk. These gang members are often known to each other. Sadly, three innocent bystanders were killed during gang warfare in the same ten-year period. Many more were put at risk. Anyone who associated with these gang members, including friends and family, was under threat of violence. In Abbotsford, a suburb of Vancouver, police issued this public notice in 2017:

If you’re anywhere hanging around with these people, you could end up being a target yourself,” said Abbotsford police Const. Ian MacDonald on Friday. “Even if you’re a friend, family member or on the periphery, there’s the potential you’re putting yourself in harm’s way.

MacDonald said that his department and other Lower Mainland police forces have been dealing with continuing gang-related violence, and that the danger goes far beyond the gang members themselves.

It is not just a possibility that those engaged in the conflict will become victims of the violence but, increasingly, it is a likelihood. Furthermore, the APD [Abbotsford Police Department] is concerned that those who associate with individuals involved in the conflict are putting themselves at risk. (Morton, 2017).

Gang Violence in Los Angeles

Not all the mayhem perpetrated by gang members is relationship violence. The following is an example of relationship violence when a recently released gang member kills his cousin but also of community violence. It demonstrates the careless disregard many gang members develop for human life.

Michael Mejia had cycled through jail many times. He had just been released following convictions for armed robbery and gang membership when he committed two horrible murders. On the night of February 20, 2017, he visited his cousin in East LA, ruthlessly murdered him, and stole his car. Fleeing recklessly through the late-night streets, he eventually crashed into two other cars. As Whittier police arrived to investigate the crash, he began shooting and killed officer Keith Boyer and wounded his partner, Patrick Hazell.

He was charged with two counts of murder and one count each of attempted murder, carjacking and possession of a firearm by a felon. He also faces special circumstance allegations of multiple murders, the murder of a police officer and murder to escape arrest, making him subject to the death penalty (Winton, 2017).

Gang Violence in London, England

Some street gang members beat and rob young people to mark their territory. They are filming these brutal broad daylight attacks on innocent teenagers and posting them brazenly on social media. In one video, the gang can be seen swarming a young man punching him, knocking him to the ground and brutally kicking him while he is on the ground. “Let me f*** this pussy over,” the leader says before repeatedly punching him in the face. In the background, a girl’s voice can be heard pleading for them to stop.

Later, the same gang filmed themselves dragging another boy off his bicycle and throwing him to the ground. They punched, kicked, and beat him with a belt before grabbing his backpack. It was all over in a few seconds. The six attackers fled in all directions while a bystander rushed to help the downed teen. According to a former gang member, these online videos are an attempt to intimidate rivals and increase credibility:

Britain is a broken country with broken families. You got ill-disciplined children in homes without an authority figure. Their mums might be handling three kids. They don’t see the Britain the others see; they don’t see hope; they see a Britain where their role model is a drug dealer (Deardon & Baynes, 2016).

These acts of violence on innocent bystanders are done just to perpetrate psychological violence on rival gangs. In Britain, a high proportion of violent crime can be attributed to street gang behaviour (Alleyne, Fernandes, & Prichard, 2014). Why do gang members commit these acts? To maintain their reputation. This is critical to many British gang members and the way they choose to earn it is through violence. That makes violence mandatory. Sometimes even a minor disrespectful action such as looking at a gang member the ‘wrong’ way triggers a violent response. If members of a gang from another postcode enter rival territory, the home members must teach them a lesson.

Not all gang violence occurs at the street level. In a research project about drug dealers in Northern England, more than 50 incarcerated drug dealers who were the ‘middle men’ in their gangs were interviewed (Pearson & Hobbs, 2003). They were responsible for buying the drugs from importers and selling them to the street dealers. Despite their violent reputation, most of these mid-level dealers tried to avoid violence so that they did not draw attention to themselves. However, sometimes violence occurred especially under the following three circumstances:

- The first was essentially external and involved violent predators who found the members of drug dealing networks to be lucrative targets for robbery. This is because drug dealers and those who work for them will often have in their possession large amounts of cash and/or drugs. Gang members engage in financial violence. Drug dealers are not usually thought of as the victims of crime, but they are.

- A second type of violence is encountered when someone centrally placed in a local drug supply scene has been arrested and sent to prison. When an imprisoned dealer is unable to keep control of his corner of the market, it is often taken over by another gang member. Violence can ensue when the dealer is released from prison and wants to re-take possession of his business. This kind of violence can be thought of as a form of middle market ‘turf war’. It is relationship violence, financial, physical and psychological.

- Another type of relationship violence (physical and psychological), which is probably the most common at this level of the market, involves kidnapping and sometimes torture. It is essentially used as a means of debt enforcement and probably occurs more often than is commonly realized; drug debtors are, after all, unlikely to report such offences to the police (Pearson & Hobbs, 2003, p. 343).

Violence in the Early Years

Gazing at a newborn, it is hard to imagine that this innocent child might grow up to stab or kill someone. How does a babe in arms, become a violent gang member? There is no simple answer as with most complex human behaviours. But we know that some characteristics that younger kids display indicate they are more likely to become violent.

Not all gang members are violent and not all violent youth are gang members. However, it’s helpful to pinpoint those factors that are specifically predictive of gang violence so that parents and professionals can work to help support these children to enhance their ability to reject violence and to demonstrate such positive attributes as forgiveness, empathy, humility, and compassion (Office of the Attorney General California Department of Justice. 2011).

Many of the risk factors for gang membership are similar to those for youth violence. Some however, are more highly predictive of serious violent behaviour than others. Young men who have a history of being violent offenders are much more likely to offend again. Although this is interesting information, waiting until an individual becomes violent (and gets caught) is an inefficient place to start. Other risk factors hold more promise.

How Children Become Violent Gangsters

Understanding and preventing gang violence is a puzzle with many pieces. Examples of the problem were presented above. But it is also important to determine the risk factors that help identify children who may become violent as they grow up. It is also necessary to pinpoint those factors that are predictive of gang violence. The final piece in the puzzle is to determine if gangs attract individuals with a tendency to be violent or whether being in a gang promotes individuals to become violent.

The Role of Emotions in Physical Violence

All humans are born with the capacity for many emotions. Anger is one of them. It is a primitive and powerful force that drives little ones to behave in ways that are sometimes shocking to adults. Anger in itself is just an emotion like many others, such as sadness. It is neither good nor bad. But learning to control their anger is an important developmental task for all children. Even infants as young as a few months old, can express their angry feelings. It is not unusual to see toddlers bite and hit others. A temper tantrum complete with yelling and kicking can be triggered because a glass of milk is offered in the green glass rather than the pink one. What parent has not seen a toddler hit when refused another cookie? What about the three-year-old who bites her thirteen-month-old-brother because he has just knocked over a carefully built tower of blocks?

Young children are often destructive. The frustration of not being able to put a dress on a doll may result in it being hurled against the floor. Tripping over a toy may mean it gets crushed. A race car that falls off the tracks may get thrown across the room breaking a parent’s favourite lamp…And that was just this morning’s troubles.

Children’s violent aggressive behaviour peaks around the age of two. By school age, most children have learned to manage their anger sufficiently to be able to interact successfully with others; at least most of the time. How does this happen? Here are some of the ways that very young children’s behaviour is shaped:

- The brain gradually develops the capacity to separate the self from others. This helps children to recognize when events happen to someone else so they can respond accordingly.

- In order to thrive socially, young children learn that striking out may invite retaliation, or they may be excluded by others.

- Clear messages of disapproval from older children and adults help children learn acceptable behaviour.

- Alternative solutions offered by adults help the child develop more socially acceptable behaviours. “Use your words”, is a common refrain used by caring adults as they help children to regulate their angry feelings. “It’s OK to feel angry but it is not OK to hit Michael.”

- As the child’s brain matures, it also develops the capacity to recall solutions other than hitting, biting, or throwing a tantrum (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2005).

Some young children (as early as three or four years old) display higher levels of aggression toward others. They are more likely (but not certain) to become violent as they reach their teen years. The key part of this sentence is “higher levels of aggression”. Future research may help differentiate the level (and types) of violent behaviour seen in children who become caring adults and those who do not. This information would help caregivers identify those children most at risk.

The development of the capacity for empathy (to feel or imagine another person’s emotional experience) is another important step for children as they learn to self-manage their emotions. This capacity begins to develop very early in life; even newborns will cry when they hear other infants crying. By two, they are beginning to have the ability to focus on responding to others in helpful ways. This is apparent in the response of a young boy, who witnessing another boy’s distress about not getting a cookie, offers his own or the little girl who helps another child who is crying because he can’t take off his boots. These early roots of empathy are important steps in developing healthy non-violent relationships with others and precursors to the child’s ability to distinguish right from wrong. From brain science, we know that toxic stress can develop at anytime, in utero to adult life. Toxic stress can impact social emotional abilities, and learning.

Parents and other caregivers can influence the development of empathy in children to a great extent and the influence starts at conception. If children form positive attachment in early life, they are more likely to learn empathy. This needs to continue, for the most of the attachment and neurodevelopment occurs from 0-3 years. As well, role modelling is important. When adults in a child’s life act with sensitivity toward others, they provide a template for the child’s future behaviour (McDonald & Messinger, 2012). The link between violence and gang life can be seen in young children who grow up in violent neighbourhoods. Violence is a feature of their everyday life. To protect themselves, they often join gangs. They are:

…aptly described as children living in urban war zones. They face a two-fold problem; these children lack pro-social adult role models to guide them and they do not have the opportunity to develop internalized self-control through developmentally appropriate play. Absence of competent, involved caregivers to provide supervision induces some children to create their own pseudo-community and acquire protection elsewhere through antisocial groups. (Reebye, 2005, p. 18)

Of course, children vary in how quickly they learn to manage their anger and they differ in their ability to self-regulate. Newborns come into the world endowed with a unique gene pool from their parents and the environment provided in the womb. Many children have less than optimal prenatal environments. For example, since alcohol crosses through the placenta to the fetus, maternal drinking may result in a variety of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). This is a condition which makes it difficult for a child to self-regulate behaviour. The prenatal environment matters (Alberta Family Wellness Initiative, n.d., Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2005).

Other children have syndromes, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder that predispose them to difficulties in learning to control their behaviour and to develop empathy. Some have Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) with hyperactivity (ADHD) (National Health Services, 2016). These are the children who shout out the answers rather than raising their hands in school; they run when asked to walk and make decisions without thinking about the consequences. Additional support is often needed for them to succeed in school, in the community, and at home. Without this help, such children may look for acceptance elsewhere, sometimes in gangs. However, most of the children and youth with these kinds of impulsive behaviours and lack of self-control do not become violent gangsters (Low and Espelage, 2014). With the appropriate help, these impulsive children can learn to channel their energy and become fully functioning members of our communities. Many of these rambunctious children grow up to become famous actors, musicians, athletes, professionals, and even politicians.

Children also vary in the quality of the interactions provided by the adults who care for them. Such negative experiences as abuse, neglect, and abandonment predispose children to being vulnerable, more likely to be mistreated by others, susceptible to joining gangs for a sense of belonging, and at risk to become violent. Children learn by modeling the behaviour of the people around them. Parents who treat others with respect and kindness give their children a wonderful gift. This is also true for others such as teachers, family members, friends, coaches, and church leaders who are a part of children’s lives. A child who grows up in a caring community is less likely to develop violent tendencies in later life. Everyone has a role.

Not all anger leads to violence and not all violence is fuelled by anger. But children who have difficulty controlling their anger are often more violent as they grow. It is important to help them learn to manage it early. Both ‘nature and nurture’ are important. If both are positive endowments, a child is supported to learn how to manage anger, behave appropriately with others, and to develop healthy social relationships devoid of violence. When there are deficits, children struggle to feel good about themselves and to be accepted by others. As teens they are much more vulnerable to becoming violent.

Violence in the Teen Years

By the teen years, all violent acts are of concern. Adolescents who are violent and their victims often experience both short term and life-long negative consequences. Many of the risk factors for gang membership are similar to those for youth violence. Some, however, are more highly predictive of serious violent behaviour than others.

Bullying is of particular concern during adolescence. Both the bully and the victim are more likely to join gangs and become violent. It is often difficult to feel compassion for teens who are violent toward others but there are many reasons why they may act as they do. These are the most common:

- They have behaviour problems such as ADHD, often beginning in childhood that result in frequent serious conduct violations at school, home and in the community. These are the youth who are often expelled from school, in trouble with the law and break the rules at home.

- They are victims of physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse. Abuse is the perfect breeding ground for rage.

- Violence in their homes (domestic violence) and/or community is prevalent.

- At school or in the community, bullies persecute them. Striking out at others is the solution they seek to end the bullying they are experiencing.

- Genetic (family heredity) factors predispose them to antisocial behaviour so they have not been able to learn to socialize well with their peers. They feel excluded.

- They have been over-exposed to violence in the media (TV, movies, and video games).

- Substance abuse is a factor in their parent’s lives or their own.

- Knives and firearms are easily accessible.

- Stressful family socioeconomic factors such as poverty, lack of parental guidance, and family breakdown are features of their lives.

- They have psychological problems such as low self-worth. The future seems bleak (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2015).

Although not all youth who experience these problems in their lives become violent, many do. They don’t understand the forces that drive them, so they turn their backs on people who can help including caring family, friends, and professionals.

Teens who grow up in homes where a parent or older sibling is pro-violence often develop attitudes of acceptance of violence as a problem-solving method that make it more likely to occur. This is evident in the story of the Bacon brothers. These three brothers, Jonathan, Jamie, and Jarrod grew up together in Abbotsford, BC a middle-class suburban community near Vancouver. All became violent leaders of the Red Scorpion gang. Together they ran an international drug trafficking operation that brought them into conflict with another gang in the Vancouver area called the United Nations gang (UN). In 2007, the Red Scorpion gang was reported to be behind the slaughter of six people in a Surrey, BC apartment building. Two of these people were innocent bystanders. Four were members of the UN gang. Jerry Langton, who wrote a book on the Bacon brothers, spoke in an interview about how the eldest brother influenced the others:

“Jonathan, the eldest of the brothers and considered the ‘smart one’, led the way for the other two. He was the ‘deal maker’ who was almost ‘statesmanlike’ in his ability to keep people together, while Jarrod and Jamie played the ‘deputy or lieutenant role’,” Langton said.

“Jonathan began by selling drugs, and was hooked by the glamour of what such quick money could buy. His brothers saw him getting away with his crimes, and were also enticed by the lifestyle,” Langton said (Langton, 2013).

Fear of lethal retaliation was a way of life for these three brothers. They were not wrong; their lives were in danger. As revenge for the brazen murder the four members of the rival UN gang, deadly plots were hatched to kill the brothers. They were described in court by a former UN gang member, C. This is the only way the man can be identified, as there is a publication ban on his name.

He told B.C. Supreme Court Justice Janice Dillon that he discussed the possibility of an aerial bombing with gang leader Conor D’Monte probably in late 2008. “We had helicopter pilots at our disposal. So, one thought was we build an aerial bomb and drop it from the helicopter on the Bacon’s parents’ house,” C testified. They decided the aerial bomb plot would be “too difficult logistically.” “You never know how big the bomb could be. You could damage or kill the neighbours,” said the long-time UN gangster who began co-operating with police last year.

Their plan to poison Jamie Bacon went a little further, C testified. “An associate of Jamie Bacon’s was trying to get him some steroids and drugs to get smuggled into the prison for him,” C said. The usual steroid dealer was out of product, so the UN saw an opening to provide the steroids, but spike them with poison first, he testified. “Conor at the time had some liquid cyanide. He had his driver bring it to me. But by the time he got it to me, it was too late to get it put into a steroid. The window closed.” (Bolan, 2017)

Today, the oldest brother, Jonathon, is dead, murdered gangland style in 2011. The remaining two brothers are in jail serving long terms for a variety of very serious offenses. For more than ten years, they thought they had it all—the adolescent dream of a dazzling lifestyle with money, fancy clothes, fast cars, and beautiful glitzy women. But it wasn’t always what is seemed. Beneath it all, the brothers were always looking over their shoulders fearful of the next attempt on their lives. They drove around in bulletproof cars wearing stolen protective vests. It was a life on the run from other gangs. Then, it all came crashing down. The glamorous lifestyle, designer clothes, and fast cars are now gone, exchanged for a drab prison life or a casket (Raptis, 2013).

Risk Factors for Violence

In a large research project of more than 5000 American youth in the eighth grade from 11 cities across the country, ten risk factors predicted serious violence (Esbensen, Peterson, Taylor, & Freng, 2009). In this study, ‘serious’ meant “attacking someone with a weapon, using a weapon or force to get money or things from people, being involved in gang fights, or shooting at someone because you were told to by someone else” (p. 318). It should be noted that over 75 percent of this sample had not committed a serious violent crime in the last 12 months. Below are those risk factors identified by this research group. They included:

- Low guilt about committing a variety of illegal acts. “It was no big deal”.

- The extent to which a youth could neutralize his feelings about a crime by believing it was justified. Violent participants explained why they did it: “Because they stole our drugs”, “Because I want to prove I can be in this gang”, “Because their gang started it”. This latter strategy is common in very young children when they are fighting over a toy and one hits the other. If asked why she hit, Mary might answer, “Because I had it first” or “Because I want it”. These excuses just don’t work beyond the sandbox. In gangs, the consequences are too deadly.

- The next risk factors were involvement with delinquent peers, a strong commitment to those delinquent friends (such as hanging out with friends who are getting them into trouble), access to drugs and alcohol, and a negative school environment. These risk factors also predicted those who would become gang members but not necessarily violent.

- There were four additional factors that predicted serious gang violence. These included impulsivity, a tendency to seek out risky behaviours, few friends who were not involved with gangs or violence, and a lack of adult supervision.

- Researchers were also able to determine if there was a cumulative effect to these risk factors. Did the number of risk factors matter? The answer to that question was a resounding “yes”. They found there was a powerful collective effect. Having more risk factors meant these youth were exponentially more likely to engage in violent behaviour. The cumulative effect was also true for joining a gang but it was not as statistically strong (Esbensen, Peterson, Taylor, & Freng, 2009).

In London (UK), a group of young people in communities known to have gangs were studied to determine the underlying moral thinking processes that enabled gang members to commit violent acts. Violent gang members in contrast to other youth were much more likely to deny the human qualities of others. They answered a series of questions such as “Some people deserve to be treated like animals” in the affirmative. This moral disengagement strategy allows these gang members to strip their victims of their humanity making it easier to hurt them. Dehumanizing victims also occurs in other violent contexts such as war, willingness to torture, and sexual aggression. Interestingly, in comparison to many American gangs, British gangs in this study had almost equal numbers of females and were often multi-ethnic, a reflection of their communities’ diversity (Alleyne, Fernandes, & Prichard, 2014).

Poor Parenting Can Have Tragic Results

There are many reports of family members influencing others to join gangs and become violent. Two brothers from London, England, followed in their father’s footsteps to become violent. Here is what one has to say:

My dad would go debt collecting and make me and my brother beat them up. He told us: this guy stole our money. He was a drug dealer so it wasn’t his money but we didn’t know. We need that money to eat, rah, rah, rah. And these were grown men, but they couldn’t do us nothing ‘cus they were scared of my dad and he’s standing there watching. So I’m 13, 14 (years old) beating up grown men, letting out all my frustration, and I’m thinking, this feels good. And my dad’s, like, for the first time, he’s proud of something. So it started with beating up grown men (Densley & Stevens, 2014, p. 111).

Do Gangs Cultivate Violence?

There is documented evidence that gang members commit more crimes and are more violent than their peers who avoid gangs (Melde & Esbensen, 2013). However, researchers have struggled to understand if youth who join gangs have a propensity for violence or if gangs promote violence in their members. To answer this question, in a large study of more than 3700 youth, the number of violent acts committed before, during and after gang membership were compared to those who had never joined. The conclusion was that gang membership itself boosted violence. For those who had been a gang member, the rates of violent offending were substantially less before joining and again after leaving. Further ethnographic research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms by which gangs cultivate violence in their members (Melde & Esbensen, 2013).

Members whose gangs are violent not only are more likely to become more violent themselves, they are subjected to more violence. They recognize they must be constantly vigilant, always looking over their shoulders to guard against attack. Their greatest risk of being a victim of violence comes from two sources ─ rival gangs and their own gang members. It is ironic that joining a gang for safety can instead dramatically increase the risk of being violently attacked.

Teaching Individuals to be Violent

The world is peopled by humans who have much more in common than they have differences. To live together in harmony on this planet, most humans must have a deep resistance to killing. Otherwise, our species risks extinction. As a result, most people are extremely reluctant to look someone in the eyes and pull the trigger. Even imagining killing creates a highly emotional, uncomfortable state of mind. So how are gang members trained to accept killing? There are a few processes.

Obedience

In order for society to function, individuals within it must be obedient. Think of the bedlam created if even ten percent of drivers decided not to stop at red lights. Children learn to obey their parents; students follow their teachers’ instructions; adults learn to comply with the law, and soldiers learn to follow the instructions of their superiors So, obedience is necessary in our society to avoid descending into chaos.

But there is a darker side to obedience. For example, in gangs, leaders take control, manipulating others to become violent by the authority vested in them. As an initiation strategy, some gang leaders demand that novices commit violent acts to prove they are obedient. Prove that they can follow instructions, sometimes to kill a rival gang member, and they are much more likely to be admitted into a gang.

The Power of the Group Process

The solidarity between members in a gang may also override any one member’s normal restraint against violence. Violence serves the purpose of demonstrating to other gang members and a frightened public that the gang members are prepared to harm others. Just like other types of relationship violence, it is about power and control.

Continuing demonstrations of violence serve to further isolate the gang from a fearful society. The cycle continues; the gang becomes more and more isolated from society because of their vicious behaviour thus promoting group cohesion amongst the members which, in turn, reinforces their motivation for continuing the violence.

In some gangs, members are bonded strongly to each other. For example, when they share a single culture, gangs are often cohesive because they share a common view of life and language. Imagining the enemy (rival gangs), as culturally inferior, stupid, incompetent and subhuman is an effective way to ‘dehumanize’ them thereby making killing easier. This is an example of what psychologists call a ‘moral disengagement’ strategy. Other tactics that gang members have been found to employ include:

- Believing that the end justifies the means;

- Relabeling their violent behaviour by using language that reduces its seriousness. Examples are: ‘Bisquit’ which is used for getting one’s gun as in ‘I gotta bisquit’. ‘Drinking milk’ is to target or kill a rival, and ‘Be on point’ means to get your gun;

- Comparing their own violent behaviour to more horrific examples such as the holocaust, thus reducing its seriousness;

- Assigning the responsibility for violence to the individuals who ordered it, rather than the person who committed it; and

- Deciding that the victim was wholly or partially responsible for the harm that they received. This strategy sometimes called ‘blaming the victim’ is done to absolve the gang members of their responsibility for committing the crime (Alleyne, Fernandes & Prichard, 2014).

In gangs, evidence of the power of anonymity can take many forms. For example, members of the public who witness gang violence often do not help the victim or even report the crime. Along with the groupthink process of assigning responsibility to others, they are afraid to get involved because of real or imagined retribution. Instead, as gun shots ring out, they retreat to their homes behind their barred windows and graffiti covered walls looking for protection from the assaults unfolding on the street. The community voice is silenced, only the violence speaks (Howard, & Crano, 1974).

Group process can impact the violent behaviour of the gang members too. They may offend in groups so that they remain faceless to both the police and community. It is more difficult to know who pulled the trigger in a crowd. Police often separate members of a gang and purposely call them by their names in an attempt to break the solidarity and anonymity of the group.

In many gangs, members also feel accountable to protect the others. When one member of the gang is threatened, all members react. To overcome the natural resistance to hurting others, gang members seldom act alone. This is also true for platoons of men in the armed forces who must learn to kill:

If he can get others to share in the killing process (thus diffusing his personal responsibility by giving each individual a slice of the guilt), then killing can be easier. In general, the more members in the group, the more psychologically bonded the group, and the more the group is in close proximity, the more powerful the enabling can be (Grossman, 2009).

When the power of groupthink takes over and reason leaves, gangs may behave in ways they might not as individuals. Under some conditions, it can lead to extremely reactive violent behaviour. This may be in contrast to other forms of relationship violence, where perpetrators don’t always believe or know they are doing something illegal. Examine this hypothetical event. Imagine that while relaxing in a public park, Ruzzo, the leader of an Hispanic gang is killed in a drive by shooting by a rival gang. All the members of the two gangs are known to each other. They went to the same school. This is an example of relationship violence between two groups of young people who are known to each other because of their shared history.

The remaining Ruzzo gang members immediately decide to retaliate. Members of the gang are in a state of heightened emotion due to the death of their leader. Their anger and grief are in full force. They start running into the other gang’s territory to kill as many as they can. Four of the Ruzzo gang are killed and two are injured. One member of the other gang is injured. Examination of the Ruzzo gang’s response to his death yields the following process:

- Consensus to attack the other gang occurred before the gang members critically evaluated alternative courses of action. For example, they could have called the police or taken the time to strategize about their retaliation so that they would be more successful.

- No one in the gang talked to anyone outside the group. Teachers, ministers, parents, friends are all sources of support who might have been able to stem the rising tsunami of emotion rolling over the group pushing them toward violence.

- Individual members of the group suspended their own independent thinking and moral code. No one suggested that the course of action they were considering could result in further deaths. Instead, of planning there was pandemonium.

- Members of the gang had an inflated belief that the chosen course of action was the right one and that they would win.

- The gang was under the pressure of a self-imposed time line. Let’s do it now!

The potent combination of these conditions led to the decision to attack and ultimately to the death and injury of more members of the gang (Boundless Psychology, 2016).

It is important to remember the group process does not always lead to negative behaviour. Sometimes individuals in groups can enact wonderful examples of acts of kindness or feats of great accomplishment. The fairy tale story of the 2015-16 English Leicester Football (soccer) team is a good example. Made up of unknown players or those released from other teams, the team members’ combined salary was less than that paid to the star player on a neighbouring team. Yet somehow, with great leadership, team cohesion, lots of effort, and bountiful community support, they managed to win the Premier League. At the beginning of the season, English bookkeepers’ odds for the team to win were 5,000 to 1 ─ the same odds that Elvis Presley would be spotted alive (Rayner & Brown, 2014).

Retaliation

In gangs with strong cohesion, members feel that they are part of an organization that needs to be protected from attack by other gangs. Neighbouring gangs compete for the same resources (usually customers who buy drugs or drug sources) so turf wars are common. Gang members also use violence to protect their reputation and demand respect. Sometimes they fight for personal reasons such as over a girlfriend. But the most common reason they fight is for retaliation. For the gang members, revenge against real or perceived threats from rival gangs is common. Fights, knifings, kidnappings, drive-by-shootings and even killings are all committed in retaliation when gang members feel threatened. Gang retaliation is like a game of ping pong; it goes back and forth, back and forth, needing ever more daring acts to proceed. The game never ends.

Not all gang violence is perpetrated against others. As noted above, in some gangs, internal fights erupt over power struggles for control especially following the death or incarceration of a leader. Then gang members may murder each other. If you are a member of a gang, you always need to be looking over your shoulder. The enemy is out to get you, but so is your friend.

When Killing is Thrilling – Appetitive Violence

Most violence occurs when individuals are in one of two states. The purpose of anger driven violence, sometimes called expressive violence is to hurt someone else. This is the kind of violence that happens because, for example, a gang member has had sex with the girlfriend of a young man in a rival gang. When it happens, the person committing the violence is in an excited state, his mind filled with a furious rage that defies all logic and overrides coherent thought.

The other type of psychological violence in gangs, called instrumental violence, happens as a means to an end such as when someone shoots a rival gang member’s girlfriend to send a message to the gang member or when gang members tie up and beat a homeowner during a home invasion. Their goal is to steal belongings, but they will harm anyone who gets in their way.

However, recently another type of violence has become increasingly common. Called ‘appetitive violence’, it occurs when people hurt or kill another for the thrill. It is done in a state of excitement when emotions are jacked up. It is not about anger or retaliation. Men and women who enjoy fighting and go looking for a reason to pick a fight display this type of violent behaviour. It is becoming increasingly common in society (Ching, Daffern & Thomas, 2012).

Some enforcers in gangs become addicted to killing and repeat it over and over (appetitive violence). One gang member describes that feeling of excitement below:

It was addicting, the adrenaline rush of doing it. It was just out of this world. It’s like you get this excitement. It’s like you’re on a high, like after you had sex with somebody, good sex, like after that orgasm and you’re just in that serene place, that’s what I felt like gangbanging (Stodolska, Berdychevsky & Shinew, 2017).

A woman spoke these words. Those powerful addictive feelings kept her locked into repeatedly violently offending against people she knew or those she didn’t. It was difficult to break this cycle for her and for others once the violence had begun.

Gang Enforcers in Vancouver

This is not quite relationship violence as NEVR defines it, but it fits because even though the perpetrator may not know the victim personally, he knows the gang and all the gangs are in a symbiotic relationship. In Vancouver, sometimes a gang member will be identified as an enforcer. His job is to commit violent acts. When he maims or kills, he is obeying orders and often does not even know his victim. He is responsible for most of the violence committed by the gang. These ‘hit men’ talk about the excitement of the planning, stalking, and the final act. Sometimes it is a beating within a gang due to drug debts. At other times, he is sent to kill the leader of a rival gang. What kind of an emotional process does he go through when he kills another man?

Part of the answer to this question, can be found by examining the stages that a soldier at war goes through to kill another human. The first stage, especially the first time, is the concern about whether or not he will freeze up when it is time to pull the trigger. This stage is very difficult to overcome and many men, even those at war, never work through this phase.

Stages of Killing (extreme physical violence)

In combat, killing is usually completed in the heat of the moment, and for the modern, properly conditioned soldier, killing in such a circumstance is most often completed reflexively, without conscious thought. It is as though a human becomes a weapon. Cocking and taking the safety catch off of this weapon is a complex process, but once it is off the actual pull of the trigger is fast and simple (Grossman, 2009). This is the killing without thinking stage.

Once a soldier successfully kills, he experiences a great emotional high called the exhilaration stage. It is due to the release of adrenaline into the system. Adrenaline highs can be very addicting because they put the body into a state of euphoria. Here is a soldier’s description of his Viet Nam experience. “In combat, I was a respected man among men. I lived on life’s edge and did the most manly thing in the world: I was a warrior at war…Only a veteran can know the thrill of the kill” (Grossman, 2009).

Some soldiers are mortified at the exhilaration they are feeling after a kill. They may believe that there is something wrong with them when they feel such satisfaction. Others thrive on the high and seek to continue the experience.

The next phase brings revulsion and horror at having killed another human being. Some researchers believe, that these feelings are rooted in a sense of identification with the victim and a sense of empathy for him. These feelings are not transitory or easy to deal with. For many veterans, the horror of killing will remain with them forever. Just when they think they are over it, a flashback will come with such force that they will be transported back to the war and relive the feelings again.

The final stage of rationalization and acceptance of their violent behaviour is a lifelong journey. It can begin immediately after the kill or years later. Some veterans never complete the task. But the process is essential to future mental health. When soldiers are not able to work through the final stage, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder may overcome them (Grossman, 2009).

Do gang enforcers who are ordered to kill go through similar experiences? Probably. After all they, like soldiers, are usually young men who are killing for the first time in their lives. Like soldiers, they often have no personal grudge against the person they kill so, they don’t kill out of anger. Like soldiers, they are following orders. In this cold-blooded killing environment, it is likely that they follow a similar emotional pattern to those in a theatre of war. The best solution to this repeated gang violence is to prevent gangs from ever happening. It will take a concerted determination on the part of every one of us to accomplish that goal.

Girls and Gangs

Are there females in gangs? The answer is a resounding, yes. Although estimates vary greatly, somewhere between one-quarter to one-half of gang members in the US are female (Chesney-Lind, 2013; Panfil & Peterson, 2015). Rates are thought to be lower in Canada and the United Kingdom (Dunbar, 2017; Disley & Liddle, 2016). Depending on where they live, females may have very different roles and responsibilities in these gangs. Just as male gangs differ from country to country and community to community, so too does the behaviour of females in gangs. In recent years, female gang members have been changing in some locations. As described by Sanders (2016), in the US, “Gang females have gone from helping their boyfriends conceal drugs and guns and supporting bogus alibis to selling drugs on the corner, shooting firearms at enemies, and requiring alibis of their own” (p. 79).

Here are the stories of four female gang members. In London, Nequela Wittaker a 30-year-old youth worker from Brixton (a suburb of South London) shares her story of growing up leading a mixed gender gang. She was eventually jailed for her gang activities and while there, decided to reform:

My nickname was “Mouthy.” I’d tell other young people to steal clothes and trainers from stores, rob people, do burglaries and sell drugs. We’d also commit crimes like not paying for taxis and joyriding, alongside excessive fighting. I’ve seen people be murdered, people’s mums being harmed, houses being run up in. I’ve seen a lot of drug taking and been in places used as a drug base. I’ve been in drug dens. I’ve seen people being beaten up, and people’s parents being beaten up and run over. My worst memory is seeing my friend’s heart get blown out of his back and no one doing anything. I was 16 at the time (Gil, 2018).

In Chicago, another female gang member, Cristina, joined a gang at 13 when her uncle handed her a gun to hold. This was her initiation into the gang whose members included her brother and uncles. In this radio interview, Christina chronicles her life as a current gang member to Yousef, the host and Peterson, a gang expert.

YOUSEF: Cristina says another way to earn gang cred is to take the fall for older male gang members. Peterson says that’s been an age-old role for female gang members since the early 1900s.

PETERSON: Specifically, because they are less likely to be looked at by law enforcement. And if they are looked at, they have been generally likely to get lesser sentences or, you know, less of a penalty.

YOUSEF: That’s even true when girls commit violent crimes. Peterson says it may be surprising, but girls are also involved in drive-by shootings. Cristina says in her gang, usually the guys would drive the car.

CRISTINA: But if the girls were in the car with them, then we had to take the gun and we have to end up shooting the other gang. I also got two points that I have to shoot. I have to pull the trigger sometimes.

YOUSEF: Do you think about that?

CRISTINA: Not really. I don’t think about it at all. It’s just like – it never comes up to my head. It’s just like – I think ’cause of everything that I’ve been through it’s just, like, I don’t feel bad for other people (Yousef, 2017).

Active gang members in Vancouver are usually male, so females often have reduced roles. They are often girl friends or wives of gang members. But that does not mean they are not involved in criminal activity and violence. Ebonay Chipman dated a young man in a gang in Vancouver. She was attracted to the wealthy lifestyle he could provide including nightclubs, jewelry, and fancy cars but one day it all came tumbling down. Here is how it happened:

Chipman’s boyfriend was heading to Bellingham(USA) with a large amount of ecstasy pills, and she went along with him. It was a routine trip for the couple…

He had arranged to meet another man in the parking lot at Bellis Fair mall, and Chipman waited in the car with her boyfriend for three hours for him to show up. Eventually, she said, a car pulled into the parking lot and he told her she could go into the mall.

I open the car door and it’s like right out of a movie. This was a Saturday afternoon, a hot day in May, May 6. The mall parking lot was full, the mall was full of f***ing people, and about 10 cars pulled out of parking spots,” she said. “I had FBI, DEA, immigration, customs, local and state police, they all got out of the cars with vests, guns pointed at me, yelling, ‘Get on the ground. Get on the f***ing ground.’ “I got on the ground. I was arrested. So was my ex-boyfriend.

After she was arrested, Chipman was sitting in the back of one of the police cars when the officer in charge knocked on the window .“They rolled down the window, he looked at me and said, ‘I hope you love him because he just took away a big part of your life’” (Kerr, 2018).

He was right; she was convicted, jailed, and served her sentence. Ebonay now speaks to college students, alongside Vancouver police, about the risks of being romantically involved with a gang member (Kerr, 2018).

In Los Angeles, it is not unusual to see girls in mixed gender gangs. One of these is the Bounty Hunter Bloods from the Nickerson Garden projects in Watts. Watts is known for its urban decay and violence. Most members of this Bloods gang are African-Americans. Like the males who join the gang, many of these females are marginalized, socially isolated, and poor (Dunbar, 2017). Some of the girls and women in these gangs are the girlfriends of gang members. In response to a question about how they get pulled into gangs by their boyfriends, a gang expert at LA Youth (2018) responded:

Another girl told us a story last week about having just completed a six-month sentence in Probation Camp because her boyfriend, who was a gang member, asked her to drive him and some friends to another friend’s home. She was told to wait in the car while they went inside. When they came running outside, they yelled at her to drive. She didn’t realize that they’d robbed the house and someone had been shot inside. The young woman ended up serving time because she was an accessory.

In an effort to understand the roles girls and women had in gangs, Miller (1975) classified their gang activities into three tiers.

- He suggested that most girls in gangs were less actively involved than their male counterparts and he labeled them auxiliary members. Also included in this tier were exclusively female gangs affiliated with their male counterparts. So, for example, the Latin Queens of Chicago were associated closely with the Latin Kings. Together they formed the Almighty Latin King and Queen Nation.

- The second of Miller’s tiers involved female only gangs independent of any male gang. These females made decisions about gang activities without any involvement or interference from male gang members.

- The final tier of gangs was the mixed-gender gangs. These were predominantly male but had a number of females.

Just as it is difficult to measure the number of males in gangs, calculating the number of girls and young women gang involved in also a challenge. It is made more difficult because females tend to leave gangs at a much earlier age than males (Sanders, 2016). So, unless they are counted when they are young, the number of girl gang members may be underestimated. However, most researchers estimate that this number has been steadily increasing since the early 1990s in the US (Centre for Social Justice, n.d.; Howell, 2007).

Many of these females are no longer content to play the supporting roles of girlfriend or wife. Some are assuming more independent responsibilities within the gangs including drug sales, recruitment, and enforcement (Dunbar, 2017; Disley & Liddle, 2016). For many observers, especially those who hold mental images of women as more nurturing and non-violent, this reality is hard to understand.

Other women, choose to be in a relationship with a gang member. However, they put themselves at risk of:

- Being sexually exploited;

- Estrangement by family members;

- Getting pregnant;

- Becoming an illegal drug user;

- Shunning by friends;

- Doing poorly at school;

- Becoming involved in criminal activities; and

- Jeopardizing her own life or those of her family members.

- This is a long list of consequences. Yet many young women fail to consider the true cost before they begin a relationship with a gang member. In the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit (CFSEU) in BC on their website, End Gang Life (n.d.), they present a section called Myths and Realities. Here is what they say about getting involved romantically with a gang member:

Even gangster’s girlfriends and wives are the target of violence and retribution. Over the past several years there have been a number of women associated in some way to gangsters murdered, some in front of their children.

A History of Abuse

Many of the women who join gangs have been abused as children. Girls with a history of being sexually or physically abused are overwhelmingly at increased risk for the development of future anti-social behaviours including problematic sexual activities (such as engaging in sex at a young age), aggressiveness, substance abuse, and becoming a gang member (Dunbar, 2017; Chesney-Lind, 2013). In a cascading downward slide that is hard to stop, many girls who have been sexually abused, drink or take drugs to forget those horrible experiences. Their need to support these habits often leads them to sell drugs which inevitably brings them in contact with gangs (Latzman & Latzman, 2015).

A 16-year-old girl describes her attempts to numb the effect of her abuse by taking drugs. About drugs, she says, “I like the feeling, I feel normal, like myself. When I am sober, I don’t like it. On drugs I am happy. Sober you think about everything. It sucks.”

Girls who have been sexually abused often feel they are different from their peers. Just how different has been the subject of many studies. It is not just their behaviours that are impacted but many are also biologically and interpersonally changed. Early puberty, increased rates of obesity, depression, PTSD, self-mutilation, and relationship problems are some of the consequences they may experience. Not surprisingly, they are also more likely to be physically and sexually re-victimized as they mature. Nor do they ‘grow out of it’. Instead, as adults, they are more likely to suffer from major illnesses and form poor partnerships with others. These women also struggle with parenting their own children. In this way, their dysfunction is passed on to the next generation. Recognizing and supporting these girls to break this cycle is an important task in every community (Trickett, Noll, & Putman, 2011).

Sexual abuse is not the only kind of cruelty that girls may face. Like boys, emotional and physical abuse also happens to them. There are painful and long-lasting consequences for any victims of abuse. For girls who experience abuse, the likelihood of joining a gang increases dramatically. Preventing abuse will go a long way to reducing the number of girls in gangs (De La Rue & Espelage, 2014, Sutton, 2017).

Although it is beyond the scope of this Chapter to discuss the protection of children from abuse in detail, there are many organizations offering help ( see chapter on abuse against children). Everyone should understand their part in reducing the incidence of abuse and finding appropriate treatment for those who are victimized. Here are some helpful sites:

The US Department of Health and Human Services Child Welfare Gateway have produced resources for a variety of topics on sexual abuse. Produced by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in the US, the Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect website focuses on prevention strategies for child abuse and neglect. In England, the PANTS program encourages parents to talk to their kids about sexual abuse to help them learn how to protect themselves.

Roles of Female Gang Members

There are many roles for females in gangs, depending on where they live. Often, they hold several at the same time. Occasionally, a girl will move from a lesser role to a full member, but the majority of females involved with gangs are there to serve the sexual needs of the males (Beckett et al., 2013). Sometimes, secondary roles are assigned to females who are not even aware that they have a role in a gang. This is particularly true of mothers and sisters of gang members who may not recognize they are involved or know they are at risk. Girlfriends may think sheltering guns, knives, money, or drugs in the family home or smuggling them into jails are just ‘helping out’ a boyfriend, but, in fact, these are illegal activities making these girls and women vulnerable for arrest and imprisonment (Disley & Liddle, 2016).

Roles that girls and young women can take may vary depending on the type of gangs in their geographical area. They include:

- Wives and girlfriends of gang members;

- Mothers of the children of gang members;

- Family members (sisters and mothers) of gang members;

- ‘Links’ who provide ‘casual’ sex to gang members;

- ‘Lures’ who entice rival gang members to a place where they can be beaten or killed;

- Sexual pawns who are forced to provide sex to strangers for money;

- Den mothers who may perform a caregiver role for others in the gang;

- Enforcers who ensure that other girls pay their drug debts;

- Secondary members who perform the non-violent work of the gang such as drug sales, spying on other gangs, and carrying messages; and

- Primary members who are involved in the full scope of gang work including violent activities such as murder (Centre for Social Justice, n.d.).

Most gang girls and women are vulnerable to sexual exploitation and violence. But it doesn’t end there, their friends and relatives are sometimes the targets of gang violence. Here are two stories of innocent girls who were victimized even though they themselves were not gang members. In London:

Stacey wasn’t involved in a gang but a friend of hers, Angie, started hanging out with one. Stacey told Angie she didn’t think one of the guys in the gang was a very nice person and Angie reported that back to the guy in question. He rounded up three mates and together they waited for Stacey after school, grabbed her just a few feet from her own front door and threatened her with a knife. They took her to a nearby block of flats and then raped her. Her ordeal didn’t stop there. They rang more friends who came and joined the attack – nine of them in total, one as young as 12, all assaulting one girl for the crime of one offensive remark (Centre for Social Justice, n.d., p. 15-16).

Former gang members report that even innocent sisters of gangsters can become targets for brutal assaults and rape. Here is one ex-gang member’s description of such an act of horrible violence:

She was walking in the park and there was a gang of boys and then that [rape] happened to her…that’s cos of who her brother was. Cos’s he’s a top boy, they thought cos they can’t get to him, cos I think he was in jail, they can’t get to him, they’ll get to her (Beckett et al., 2013, p. 18).

Sexual Exploitation of Female Gang members

Interviews with current and former gang members indicate that some females were repeatedly raped by several gang members. At other times, they may be forced to give oral sex to many gang members, one at a time, while the others watch. Some females are ‘sexed in’ when initiated into gangs. This means that they ‘agree’ to have sex with several gang members before they can join. The paradox for many girls and women in gangs is that although they join to avoid being hurt by rival gangs, they are at risk for physical and sexual victimization by their own gang (Disley & Liddle, 2016; Beckett et. al., 2013).

A British study of gang associated sexual relationship violence, involved 188 interviews with gang members to determine the scale and nature of the problem and to determine possible interventions Beckett et. al., 2013). The findings indicated most incidences of sexual violence were committed by males in male only gangs. The researchers found, “Risks of sexual violence and exploitation are heightened within the hyper-masculine environment of these gangs” (n.p.). They also discovered almost all the violent sexual acts were perpetrated by males with females they knew through their gang involvement. They were seldom reported.

In these interviews, various forms of sexual violence were identified. The most frequently discussed are listed below:

- 65% shared examples of young women being pressurized or coerced into sexual activity. As reported by an 18-year-old young man: “once they’ve implemented that fear into them it’s easy to get what you want”;

- 50% identified examples of sex in return for status or protection. Whilst this is not unique to the gang environment, in a world where ‘respect’ and ‘status’ are seen as essential for the male, the need to achieve these is acutely heightened;

- 41% shared examples of individual perpetrator rape; and

- 34% shared examples of multiple perpetrator rape. Some were explicitly conceptualized as rape, and seemed to be motivated by a desire for retribution or control. Many others were viewed as ‘normal’ sexual behaviours with little recognition of the fact that the absence of consent constituted a sexual offence. As noted by a 15-year-old young woman: “He feels in control of the streets anyway …so he’ll want things to go his way, so he won’t be thinking ‘oh this is rape’, when it actually is.”

Female gang members in London exist but as elsewhere, their numbers are largely unknown. Most are viewed by male gang members as associates who play a secondary role in the activities of the gangs. They are asked to stash weapons, money, and drugs, often in their bedrooms at their parents’ houses. When needed, they are expected to provide an alibi for gang members to the police. These girls and women sell goods stolen by gang members and are the drivers who move drugs around. Often, they can get away with these activities because they are largely unknown and overlooked by the police. The irony is that when male gang members perform these same activities, they are treated as serious crimes by the authorities (Medina et al., 2012).

However, females have another dangerous role: providing sex for the gang members. Some are used for spontaneous sexual activities. Derogatory language is used when they are talking about their casual sexual partners. They are ‘sluts, slags, bitches, whores, or tramps’; and they are to be shared with others. “We call them sluts, girls you have sex with because you can, because anybody can, they’re just easy” (Trickett, 2016, p. 30). These terms have a shaming effect and cast a slur on female sexuality.

In contrast, girlfriends and wives are treated differently. “Your ‘bird’ is when you are talking about your girlfriend, you know, the missus, that means she’s yours basically and any other bloke must keep his hands off” (Trickett, 2016, p. 30). In these gangs, girlfriends are treated like objects to be guarded; other girls are passed around without a thought.

Male gang members in Britain are respected by their peers for the way that they express their sexuality. If they uphold the ‘code’, they will be honoured; if they ignore it, they will be stigmatized. Here is the code as determined from interviews with gang members (Trickett, 2016).

- Young men should always be looking and ready for sex;

- The purpose of sex is to give pleasure to the male;

- Masculinity is demonstrated by the number of sexual encounters with the opposite sex;

- Promiscuity is encouraged for men (but not for girlfriends);

- Talking about casual sexual experiences with the other gang members is expected;

- Violence is used to defend or protect girlfriends;

- Consent for sex is not necessary; and

- Responsibility for disease and pregnancy is solely a women’s:

- Condoms are “unmanly” and not worn,

- Girls are responsible for birth control,

- Girls are the cause of sexually transmitted infections; men are not carriers.

Inter-gang rivalry is often initiated by disputes over girlfriends. Here, a gang member talks about his problems when he ignored this part of the code:

There’s a few blokes that have just come out of prison that are looking for me… I did something with his missus (sex) whilst he was inside. I didn’t know he was going out with her, but my friend had done it as well, with another bird he was seeing before he was inside. He kidnapped him. We were walking down the road and he jumped out of a car with a knife and put it to his throat and forced him into the boot” (Trickett, 2016, p. 34).

Being the girlfriend of a British gang member is not easy or safe. There is always the risk of being hurt or killed by rival gang members in retaliation for some real or imagined wrongdoing. As a result, girlfriends are often severely restricted about where they can go and with whom.

“Your girlfriend is a target without a doubt, some women round here have been targeted because someone is after us… You have to try to prevent stuff, most girls won’t go out without male protection cos they’re not allowed to” (Trickett, 2016, p. 34).

Many British girls are trapped into gangs. They feel they have no choice but to become involved. This is the story of a young girl who grew up with her father and three younger siblings in a low-income area in England as told by her case worker. Sadly, experiences like these are not uncommon:

When the girl was 11-years-old she started dating a 14-year-old boy she met at school and who was in a gang. He often tried to persuade this girl to have sexual intercourse with him, and by the age of 12 she agreed. Soon afterwards the girl found out that he had filmed them having sexual intercourse on his laptop. At this point the girl described to her worker that this boy’s attitude towards her changed dramatically and he became aggressive and cold. The boy threatened to show her father the footage and post it on various social networking sites for all of their friends to see. The idea of this happening terrified the young girl and she begged him not to do it. He agreed not to share the footage, on one condition: that she must always be available to both him and any other gang member for sex. She was horrified, but was so scared about what her family and friends would think of her if they saw the video so she agreed to his terms.

From this moment on the 12-year-old girl’s life descended into one of regular abuse and sexual exploitation. She was raped on a weekly basis, and many of these crimes were filmed and played back to her by her rapists. On one occasion she was forced to give oral sex to around 20 gang members as they stood around her in a circle and beat her. She became so desperate she would have done anything to make it stop.

The gang then offered her a way out: if she found new girls for them, they would stop raping and abusing her. Again, she agreed. The gang asked her to make friends with girls her age or younger. Once she had made friends with other girls, she would invite them round to her flat where roughly 20 gang members would be waiting. Each time they would rape the new girl, and film the encounter to entrap the new girls. (Centre for Social Justice, n.d., p.7)

Click here to watch a BBC News video of interviews with young girls about how they were groomed into gangs in London, England.

Here is one frightened girl’s story:

Let me give you an example of why people don’t [go to the police]. Because if you go to the police station and say ‘this gang member raped me’ that gang member might be found guilty and go to jail, but remember he’s part of a gang. So all the ones in the gang, 500 people, 400 people, will come back to you, to your house. Could go to your family’s house, you know. So you might as well keep it on the low and move on with your life innit (Beckett et.al., 2012, p.11).

For many of these girls, life passes in a blur of escalating violence both as perpetrators and victims. Although some find the life of fear punctuated by sudden adrenaline rushes exciting and financially rewarding, for most, by the time they want to leave the gang, they discover that life has passed them by. “Where do you go from there? Your childhood has vanished” (Combi, 2013).

‘Gang Girls’ of America

Like most countries, no one knows how many girls and women are involved in gangs in the US. Estimates vary so much that all that can be said is that there are fewer girls in gangs than boys, but more than most people think. Almost all the attention in the media and academia, has focused on boys and men. However, there are a number of trends with girls in US gangs that seem to be more common than elsewhere.

The first is all-girl gangs. This type of gang has been reported elsewhere, but recently there has been an alarming increase in these girl gangs in cities such as New York and Chicago. With names such as Harlem Hiltons and Bad Barbies, these sister gangs sometimes affiliate with male gangs but often are independent. In an attempt to set themselves apart, many avoid using the term ‘gang’ and instead use monikers such as ‘crew’ or ‘set’ (Howard, 2015).

Chicago’s Girl Gangs

Chicago’s South Side has traditionally been a hotbed of violence but one murder in 2014 was out of character even in this neighbourhood. The victim was not a male high school drop out. Instead, a female, Gakirah Barnes, was killed. She was a graduate of a charter-school who had done well in her studies. But behind this seemingly optimistic façade lurked a homicidal gang member who had been involved in 20 gang murders; the first at age 14. Her media footprint bore witness to her lethal activities. Just a few days before she was killed, she had posted a photo of herself with a .357 Magnum revolver. The day before she died, she tweeted the lyrics, “u Nobody until Somebody kill u dats jst real Shyt”, by a rapper who called himself, The Notorious Big (Biggie Smalls). Biggie had been killed in Los Angeles in 1997 (Daly, 2014).

The US proximity to Mexico and Central America has also influenced gang behaviours that negatively impact girls. Increasingly, the sexual trafficking of young girls, some as young as nine years, who are newly arrived (often illegally) from these countries is replacing the traditional gang activities of selling drugs and stolen goods. In fact, more than 35 states have reported the existence of gang involved sex trafficking (National Human Trafficking Hotline, 2014).

Of course, not all traffiked girls are from other countries. It has been estimated that an American girl will be approached by drug dealers and pimps, many of whom are gang members, within 48 hours of landing on the street. Some of these runaway girls are attracted to the gangs because they offer protection from the dangers of street living. Most girls are unaware that once they get involved in gangs, they may not only be raped or abused by their fellow gang members but also trapped into selling their bodies for sex with strangers (International Association of Chiefs of Police, n.d.).

Many of the American girls who are lured into sexual trafficking by a gang member have come from troubled families where they have been ill-treated and abused. As a consequence, they have reduced self-esteem and little confidence they can make a satisfying life for themselves.

Gang-involved sex trafficking has slowly come to the attention of the police and the general public. It is a form of human bondage that victimizes many young people at vulnerable times in their lives. To be considered sex trafficking by law enforcement agencies (in most places), it must include using force, fraud, or coercion to exert power over someone to perform a sexual act for money. It should be noted that if the girl is under the age of 18, the use of force, fraud, or coercion is not necessary to prove trafficking (National Human Trafficking Hotline, 2014).

In the US, this type of the sexual victimization of young women has been called modern-day slavery. Even when girls are rescued from this enslavement, they struggle to re-enter society and engage in age appropriate activities. Even though the threads that hold a girl to the gang are invisible, they are strong enough to ensnare on her mind. Here is a typical story:

It still affects me … in a very, very scary way. I am scared when I walk out the door to walk to the bus to go to school. In class, I am scared to raise my hand. I am scared someone is going to hurt me. I am scared to sit in the front row because there are too many people behind me I can’t see (Neubauer, 2011).

US Three-Strikes Law Affects Girls in Gangs

Oddly, the American justice system itself created a law that has had an inadvertent negative repercussion for girls in gangs —the Three-Strikes Law. It was adopted in 24 states in the 1990s. The law was originally voted in by Californians in response to the brutal murder of a teenage girl by a repeat offender. The citizens voted to ensure this would never again be able to happen. As a result of the passage of this law, too many people (mostly men) have gone to jail for 25 years to life for committing three minor offenses (Taibbi, 2013).

So what does this have to do with girls in gangs? While many boys and young men in gangs have criminal records, not many are willing to risk a third offense even after the 2012 amendments softened the original law. So, wives, girlfriends, and female gang members are expected to ‘take the fall’ for them. Hiding drugs, stolen property and weapons with a female, especially one who is unlikely to disclose their true owner, may make sense for young men, but it puts their female counterparts at risk for criminal records (and jail time) for crimes they did not commit. The irony is that a law designed to protect women ends up hurting them.

Mom, They Don’t Shoot Girls – Vancouver Gangs

Brianna Kinnear believed that as a girlfriend of a gangster she would not be killed. She was wrong. In 2009, she was shot dead with her little dog by her side. She was 22 years old. Her boyfriend, a gang member, was well known to police. What Brianna believed was a myth. The truth at the time Brianna spoke those words, was that six gang-involved women had been murdered in the preceding ten years in BC. As in other places, the taboo on violence against girls and young women associated with BC gangs is changing (Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit, 2015).