2 The Process of Developing Interculturality

Learning Objectives

By the time you finish this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain why intercultural development is a process.

- Outline the steps in the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS).

- Describe a possible behaviour you might observe at each stage of the DMIS.

- Explain the limitations of the DMIS.

In the last chapter, we introduced the idea that intercultural development is an ongoing process. It requires developing new attitudes, new knowledge, and new ways of behaving. Like any process of personal development, we don’t achieve high levels of growth instantly.

When you completed your self-reflection, you might have noticed areas that require further development. The fact that you’ve noticed these is a strength, and indicates that you are growing in the self-awareness needed to direct your intercultural growth. In this chapter, we will build on your knowledge by introducing one model, the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.

The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity

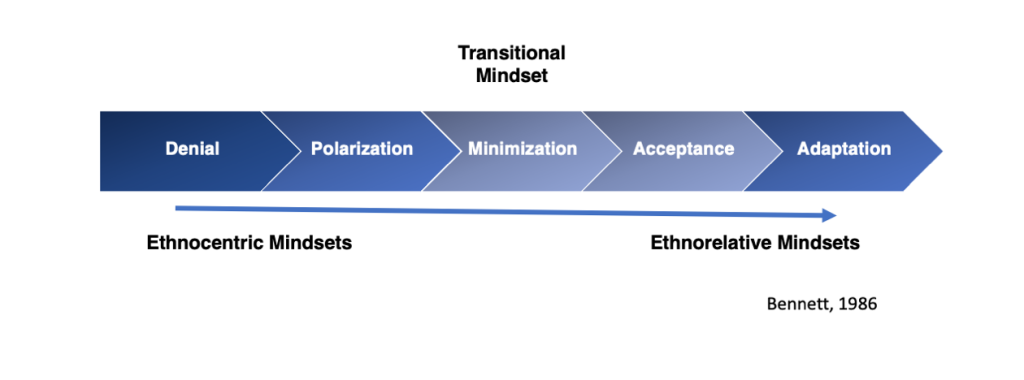

The Developmental Model of Sensitivity (DMIS) was developed by Milton Bennett, and outlined in an article first published in 1986 (Bennett, 1986). The DMIS is designed to help us understand how we change in the ways we understand and approach differences as we grow interculturally.

The DMIS states that we move from ethnocentric ways of interacting with the world towards ethnorelative ways. Ethnocentrism is a way of viewing the word through the perspective of our own cultural worldview. In this stage in our development, we tend to believe that our culture’s way of seeing the world is the one that is most normal, and perhaps most correct. We struggle to change our point of view in ways that move between cultures and perspectives. In ethnorelative stages, we are able to more clearly understand the different cultural viewpoints and perspectives that exist, and to move between these more fluidly. We are able to see that these perspectives are not necessarily “right” or “wrong”, but reflect differences. We are able to respond to difference with positive emotional and thinking strategies, and move between ways of behaving more fluidly.

The DMIS model assumes that everyone starts from ethnocentric perspectives, and moves towards ethnorelative perspectives as intercultural learning and practice continues. This progression is natural, but not automatic – we need to intentionally seek to grow.

While Bennett (1986) included six stages in the model, the most frequently used version of this framework, known as the intercultural development continuum names five stages: Denial, Polarization, Minimization, Acceptance, and Adaptation. (IDI, LLC, 2017).

Denial is generally characterized by unawareness of cultural difference. It is a monocultural mindset, where the focus is placed on a single culture—one’s own—and reflects limited experience interacting with other cultures. For some individuals, denial can look like disinterest in cultural difference, and for others, it may reflect avoidance of other cultures.

Example: Raj is a student who has never traveled outside his home country. When his university organizes a cultural diversity week, he shows little interest, commenting, “I don’t see why we need to learn about all these different customs. People are basically the same everywhere.” When his roommate suggests they attend a cultural festival featuring foods and traditions from various countries, Raj declines, saying he’d rather stick with familiar activities. In group projects, Raj becomes uncomfortable and disengaged when international students share perspectives that differ from his own. He tends to attribute these differences to individual personality traits rather than recognizing how cultural backgrounds might shape their viewpoints. When confronted with unfamiliar cultural practices, Raj often remarks, “That’s just weird,” without attempting to understand the cultural context behind them.

Polarization reflects an increasing awareness of cultural difference. In polarization, individuals tend to respond to cultural difference from an evaluative frame of mind, judging differences in relation to one’s own culture. There are two sub-types of polarization: defense, which places a high value on one’s own cultural practices when responding to difference, and reversal, which judges one’s own culture more negatively in relation to others.

Example: Mei works at an international marketing firm where she frequently interacts with colleagues from different cultural backgrounds. When her team begins collaborating with the company’s European branch, she often makes comments like, “Our approach is much more efficient than theirs. They waste so much time on lengthy discussions when we could just make decisions and move forward.” During video conferences, Mei becomes visibly frustrated with her European colleagues’ communication styles, later telling her local teammates, “They’re so indirect and take forever to get to the point. Our way of being direct and task-focused clearly works better.” When her manager suggests that Mei adapt some of her communication approaches to bridge cultural differences, she defensively responds, “Why should I change? Our office consistently outperforms theirs in meeting deadlines.” Mei’s polarization mindset leads her to evaluate cultural differences through a lens that favours her own cultural practices, making effective cross-cultural collaboration difficult.

Minimization is a transitional mindset, where individuals begin to move away from an ethnocentric mindset, towards a more relative approach to relating to cultural difference. Individuals with a minimization mindset focus on similarities and commonalities as a way of negotiating differences, and may place a high value on seeing others within the frame of common humanity. For individuals from groups with greater social power and representation, a minimization mindset may reflect more limited understanding of one’s own culture as a factor in intercultural interactions, while for members of groups with less social power or representation, this may reflect a strategy of “go along to get along” in intercultural relationships.

Example: Emma is an undergraduate student participating in a diverse study group for her GLBL course. When her classmates from other countries express difficulty adjusting to the professor’s teaching style, Emma responds, “I think you’re overthinking this. We’re all just students here trying to learn the same material.” During a group project discussion where cultural perspectives on the topic emerge, Emma quickly redirects the conversation by saying, “At the end of the day, we all want the same things in life. We should focus on our common humanity rather than our differences.” When the study group is deciding how to divide work for their presentation, Emma dismisses concerns about different cultural approaches to academic work, saying, “Let’s not complicate things by focusing on differences. University is the same for everyone, and good study habits work for everyone regardless of where you’re from.” Though well-intentioned, Emma’s minimization approach prevents her from recognizing how cultural factors genuinely impact her classmates’ educational experiences. Her emphasis on similarities allows her to avoid examining how her own cultural background shapes her academic approach and interactions with peers from different backgrounds.

Acceptance is an intercultural mindset where individuals are able to recognize and appreciate both similarities and differences between cultures. In acceptance, individuals have a greater awareness of their own cultural values and those of others, and are able to respond to these differences non-judgmentally. Individuals with an acceptance mindset may have difficulty fully adjusting behavior in response to what they observe and understand.

Example: Aisha is an undergraduate student participating in a diverse study group for her GLBL course. When her classmates from other countries express difficulty adjusting to the professor’s teaching style, Aisha responds, “I think that’s actually a fascinating cultural difference to explore. Each of us brings unique educational expectations shaped by our backgrounds.” During a group project discussion where cultural perspectives on the topic emerge, Aisha eagerly embraces the conversation by saying, “At the end of the day, these different viewpoints are what make our project stronger.” She shows genuine curiosity by asking thoughtful questions about her peers’ cultural contexts rather than focusing only on similarities. When the study group is deciding how to divide work for their presentation, Aisha acknowledges concerns about different cultural approaches to academic work, saying, “Let’s explore how these various approaches might complement each other.” Though she is generally flexible and open in her approach to cultural difference, sometimes she fails to apply her knowledge in practical situations. For example, last week she was introduced to a new colleague from a culture where men do not prefer to shake hands with women. Though she knew this information, in the moment she forgot and reached out to shake hands.

Adaptation In adaptation, individuals are able to shift both cognitively and behaviorally in intercultural interactions. They are able to practice empathetic attending in their relationships, and respond accordingly. A challenge for individuals in adaptation may be impatience and frustration with others who are at earlier stages in their intercultural development.

Example: Jamal is a project manager at a multinational tech company where he leads a diverse team with members from five different countries. When his Japanese team member expresses hesitation about directly challenging ideas during meetings, Jamal adapts his communication approach by saying, “I understand that in your culture, disagreement might be expressed more subtly. Let’s try using a written feedback system before meetings to gather everyone’s honest opinions.” During client presentations, Jamal seamlessly adjusts his communication style based on cultural context—maintaining appropriate eye contact with American clients while respecting the preference for less direct eye contact with some Middle Eastern partners. When planning team celebrations, Jamal demonstrates his adaptation mindset by consulting team members about their cultural preferences, saying, “I want to ensure our events respect everyone’s values while still building team cohesion.” Rather than simply acknowledging cultural differences, Jamal actively shifts his behaviour to communicate effectively across cultures without compromising his own values. His ability to evaluate situations from multiple cultural frames of reference allows him to navigate complex international projects while maintaining authentic relationships with team members from diverse backgrounds.

Strengths and Limitations of the DMIS Model

The DMIS model provides us with a useful tool to understand ourselves and others as we grow interculturally. By self-assessing our current attitudes and behaviours according to the model, we can gain insight into our next development steps. A barrier, however, is our tendency to assess ourselves at a higher stage than might be the case in reality. Because we view the characteristics of acceptance and adaptation as positive, and aspire to practice these things, we may inadvertently believe we are at these stages when we are still working towards this level of growth.

Another limitation of the model is its assumption that intercultural development and behaviour is always linear. In reality, this might not be the case. For example, in a situation where we are more comfortable, we might exhibit attitudes and behaviours characteristic of the minimization stage. When under stress, like when in the first months in a new country where we might be affected by culture shock, we may move more towards traits of the polarization stage. While it is true that we generally move towards growth, it is also important to recognize that we may experience shifts from time to time. Recognizing this limitation also reminds us that we need to maintain a focus on intercultural growth, and that continual development is not guaranteed (Acheson & Bean, 2019).

Reflection Point:

- Where do you think you might find yourself on the intercultural development continuum right now? What attitudes, statements, and behaviours might provide evidence of this?

- What changes do you think might be needed to move to the next stage in your development?

Chapter References

Acheson, K., & Bean, S. S. (2019). Representing the intercultural development continuum as a pendulum: Addressing the lived experiences of intercultural competence development and maintenance. European J. of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management, 5(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJCCM.2019.097826

Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90005-2

IDI, LLC. (2017). The Intercultural Development Continuum. https://idiinventory.com/products/the-intercultural-development-continuum-idc/

AI Use Statement

Examples for each stage of the Intercultural Development Continuum were adapted from content generated by Claude (2025, May 20). [Content generated by Claude 3.7 Sonnet]. Anthropic.