12 Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Justice

Learning Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (JEDI).

- Distinguish the difference between equity and equality.

- Connect DEI with justice.

- Compare organizational rationales for engaging with JEDI.

What is DEI/JEDI?

In the previous chapter, you explored the practices related to working in diverse workplace teams. If you aspire to work on a team, or to become a leader in your workplace, another important step in your learning is to explore the bigger picture of what leads to inclusion and fairness in teams, organizations, and society more broadly. The concepts that can help us to consider whether our organizations create belonging and justice for others are often described as DEI (or EDI), which stands for diversity, equity, and inclusion. We will also connect this with justice, the goal of EDI practice.

Diversity

The concept of diversity means understanding that each individual is unique, and recognizing our individual differences. These can be along the dimensions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs, or other ideologies. Diversity is a reality created by individuals and groups from a broad spectrum of demographic and philosophical differences. It is extremely important to support and protect diversity, to value individuals and groups without prejudice, and foster a climate where equity and mutual respect are intrinsic.

Diversity is a fact we can observe in many Canadian contexts, and can lead to stronger teams and societies when it is acknowledged as a source of different perspectives. However, diversity is not the end goal of DEI, as it is generally a measure of “who is in the room”, and not whether fairness or belonging are present (Zemsky, 2018). For example, an organization may include people from a variety of ethnicities and social identities, but yet have processes for hiring or promotion that do not provide a fair opportunity for all qualified employees to advance to more senior positions in the organization.

Equity

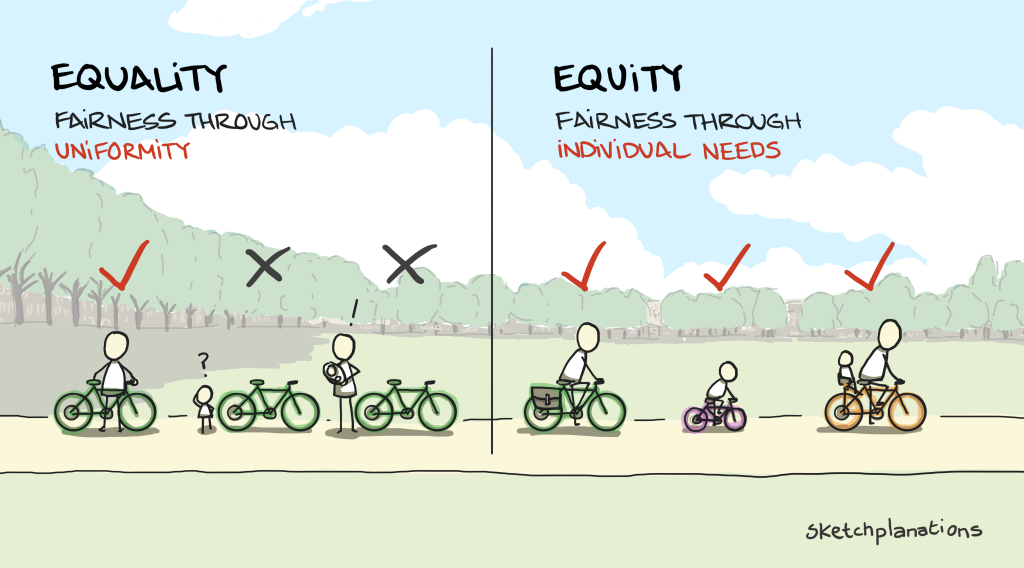

Equity is the next key principle to consider, and relates to thinking about what is fair. Equity is often confused with equality; however, these are not the same. Equality suggests that everyone receives the same treatment, while equity suggests that everyone receives what is needed for an equal chance to thrive in their environment. Processes focused on equity take individual needs into consideration. For example, a neurodivergent team member may benefit from modified communication strategies, while a team member who uses a wheelchair may need an office layout that allows all needed work supplies to be in easy reach.

Equity does not mean that everyone is guaranteed to have the same outcome, or that someone may gain an advantage that they don’t need or deserve. Rather, the principle of equity aims to provide everyone with the opportunity to reach their full potential, either individually or within an organization.

Inclusion

Inclusion is the next step in the DEI process. When inclusion is present, every member of a team, organization, or community feels that they belong, regardless of individual characteristics or social identities. Another words that is often used for inclusion is belonging. When inclusion is well-developed, people feel free to share their ideas, to disagree with others, and to share aspects of their identity with others without fear. An inclusive environment aims for a sense of belonging among all employees, equitable treatment regardless of background, the integration and celebration of diverse perspectives, mutual trust between colleagues and leadership, shared decision-making processes, and an atmosphere where people feel psychologically secure to express themselves. Inclusive people and organizations strive to eliminate obstacles, end discriminatory practices, and interrupt intolerant behaviors that might prevent any individual from fully participating and thriving in the workplace. In other words, members of inclusive environments experience psychological safety (Warner et al., 2019).

Reflection Point

Have you experienced a situation where diversity was present, but equity or inclusion were not achieved? Why did this occur? What was the impact on you and other people?

Justice

Sometimes, rather than EDI, the acronym JEDI is used. This shift is made to make the link between EDI and justice clearer and more explicit. The JEDI acronym helps us to remember that our purpose is to work towards justice — whether at at an individual, team, organizational, or societal level.

Reflection Point

Read the definitions below. Which resonate most with you? Which seem to connect most with JEDI?

- “Justice is the bond of men in states; for the administration of justice, which is the determination of what is just, is the principle of order in political society.” — Aristotle (4th century BCE)

- “Justice is a habit whereby a man renders to each one his due by a constant and perpetual will.” — Thomas Aquinas (13th century)

- “To go beyond is as wrong as to fall short. In matters of justice, the middle way is the true way.” — Confucius (6th-5th century BCE)

- “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” — Martin Luther King Jr. (20th century)

- “Justice delayed is justice denied.” — William E. Gladstone (19th century)

- “Non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good. Justice never comes to a nation without struggle.” — Mahatma Gandhi (20th century)

Why Engage in JEDI?

In organizational contexts, two major rationales have been suggested for why organizations should engage in JEDI. The first is the business case. This approach recognizes that organizations often benefit when teams are diverse and when multiple perspectives are used to make high quality decisions. The business case also acknowledges that when team members are included and feel a sense of belonging in an organization, they are more likely to stay in their role and progress in the organization. This means that organizations are more likely to retain their best talent, rather than losing key performers to competitors. The business case highlights the potential of diverse teams to engage with a wider client or customer base. In addition, equitable organizations are likely to maintain a strong reputation (Forbes, 2023).

The business case has also been critiqued. Georgeac and Rattan (2022) highlight that while most organizations use the business case when discussing their JEDI efforts, the fairness case may be more important. Their research highlights that those that organizations intend to retain through JEDI efforts generally feel a lower sense of belonging when reading the business case, as they may feel as though they are being used as means to an end for their employers. Instead, treating employees in ways that are fair may be more likely to generate a true sense of belonging and fairness for all.

Doing JEDI Well

You may be surprised to discover that JEDI has become controversial in some contexts. Often, this is connected to inaccurate understandings of JEDI and/or contexts where JEDI has been implemented in ways that do not support psychological safety and inclusion for all. Thinking about JEDI well requires us to understand key definitions accurately. When individuals or organizations seek to create educational programs related to JEDI, this also means ensuring that these programs are grounded in psychological safety and a strong understanding of how to support people in their learning. Often, leaders in JEDI work are at the acceptance or adaptation levels of the DMIS; however, this may mean that they may have weaknesses in helping those who are earlier in their development without becoming impatient.

When we seek to implement JEDI, we require a range of skills. These include:

- Strong understanding of our cultural contexts and the historical factors that have shaped them.

- Well-developed emotional intelligence skills.

- An ability to recognize the human dignity of all, and to facilitate inclusion across cultural identities.

- The ability to choose content and learning activities that are appropriate to the learning needs of participants.

When we are discussing issues related to JEDI, particularly if we have a strong tendency to focus on justice and fairness, we can fail to recognize and honour different perspectives, creating barriers between those who are not 100% in agreement on all issues. When doing JEDI work, we should maintain our ability to recognize multiple perspectives and work together with those who are different from us (Ross, 2025). This requires wisdom to consistently uphold human rights and fairness for all while honouring diverse perspectives and needs.

Chapter References

Forbes. (2023, May 11). The business case for equity, diversity and inclusion. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2023/05/11/the-business-case-for-diversity-equity-and-inclusion/?sh=718f28722838

Georgeac, O., & Rattan, A. (2022). Stop making the business case for diveristy. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/06/stop-making-the-business-case-for-diversity

Ross, L. J. (2025). Calling in: How to start making change with those you’d rather cancel (First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition). Simon & Schuster.

Warner, M., Bedok, N., Rau, H., & Bajaj, D. (2019). Organizational Behaviour. Seneca College. https://pressbooks.senecacollege.ca/organizationalbehaviour/

Zemsky, Beth. Intercultural Definitions. (2018, October 31). [Video recording]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w67YIN72r6M

Adaptation Statement: Some content adapted from Looking at Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the open textbook The Role of Equity and Diversity in Early Childhood Education by Krischa Esquivel, Emily Elam, Jennifer Paris, & Maricela Tafoya. CC BY license.